Ida FRIEDMANN (1927-2015)

The story of a Holocaust survivor, deported on Convoy 77

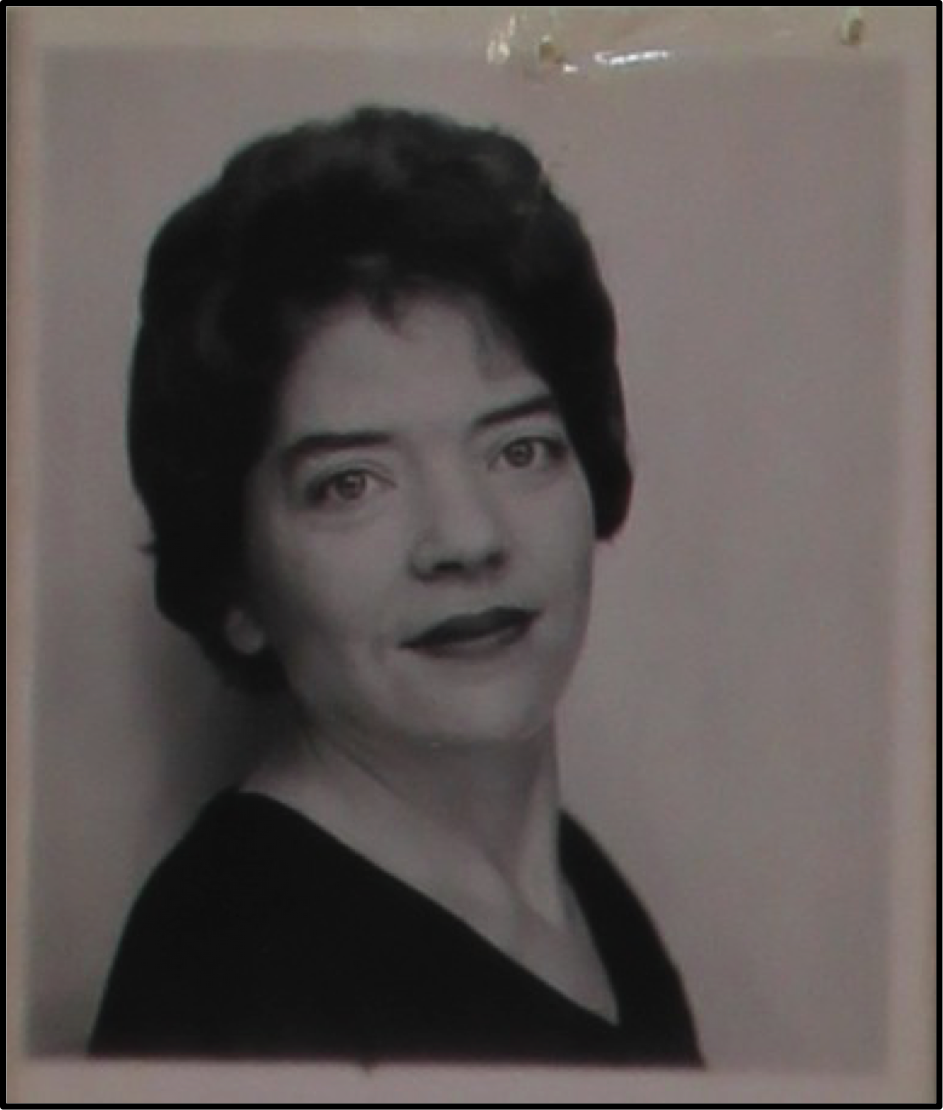

Ida Friedmann, identity photo, 1950

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Normandy

Introduction

Ida (also known as Irène) Friedmann, one of countless Holocaust victims, was persecuted simply because she was born Jewish. Her mother died when she was just three years old, after which her father placed her in an orphanage. Her father, a Jewish communist resistance fighter, was handed over to the Germans by the Vichy government and shot when Ida was just 14. At the age of 16, Ida herself was deported, together with 1305 other people, on Convoy 77, which left the Bobigny train station for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. Despite this difficult and remarkable start in life, she was incredibly lucky to made it out of the camps alive: of the 76,000 Jews deported from France between 1942 and 1944, fewer than 4,000 came home. Ida managed to overcome this horrendous ordeal and, with tremendous fortitude, dedicated her life to paying tribute and preserving the memory of her father. One of the ways she did this was by joining the French Association nationale des familles de fusillés et massacrés de la résistance française et de leurs amis (National Association of families of those shot and massacred in the French Resistance and their friends).

Focusing on Ida’s life involved exploring the history of the Holocaust from one individual’s point of view, in order to better grasp the finer details. It also entailed gaining a better understanding of Convoy 77 and how it differed from other convoys. As operations Overlord and Bagration took their toll on Axis troops, and news of the attempt to assassinate Hitler spread confusion through the Nazi ranks, Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy internment camp, hastily arranged a series of roundups. He was determined to fill one last transport to Auschwitz: the train left on July 31, 1944, and became known as Convoy 77.

The main difference between this and other convoys, which reflects the circumstances in which it was organized, was the exceptionally large number of children, many of them orphans, and women. This was largely the result of roundups targeting children’s homes in and around Paris, in particular those run by the UGIF (Union générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews), whose leaders were arrested in 1944.

Ida Friedmann also symbolizes the Second World War in a broader sense, as it is a subject that cannot be discussed without including the Holocaust. The attempted annihilation of the Jews and the war overall claimed 45 million civilian victims, including 6 million Jews, which was around 75% of the Jewish population of Europe.

In this biography, we present the results of our research. We investigated Ida’s childhood and her wider family, which were the decisive factors in shaping the rest of her life, her arrest and deportation, which marked a turning point for her, and also the long-term repercussions they had after she was repatriated and her life back home in France, and how she managed to rebuild her future.

Ida Friedmann’s childhood and adolescence

Ida Irène Friedmann came into the world on December 9, 1927, in Paris. Her father’s family was from Poland and her mother’s from the Ottoman Empire. Both were Jewish, and she was their eighth child. She also had a half-brother and half-sister from her father’s second marriage. Her parents were Bernard Friedmann, who was born in Warsaw, Poland, on December 31, 1886, and Sabina Segal, born in Constantinople, Turkey, in November 1889. Bernard Friedmann, an Ashkenazi Jew, emigrated to France from the Russian Empire to escape anti-Semitic persecution there and in search of a better life. He was naturalized as a French citizen on December 13, 1927. As for Sabina Segal, her family were Sephardic Jews. She emigrated to France from the Ottoman Empire. The reasons she left are unclear, but may have been related to financial circumstances and again, a quest for a better quality of life. Bernard Friedmann and Sabina Segal were married on June 4, 1925 at the town hall in the 4th district of Paris.

During the First World War, because they were foreigners from enemy or neutral countries, the family was held in a camp for “Turks” in Pontmain, in the Mayenne department of France. Although the French authorities called it a “concentration camp”, it had nothing in common with the Nazi concentration camps of the Second World War. It was an internment camp nonetheless, intended to detain foreign nationals from countries with which France was at war and who were present in the country from August 1914 onwards. This explains why three of the Friedmann children, Louise, Edouard and Isabelle, who were born in 1915, 1917 and 1919 respectively, were all born in Mayenne.

Bernard Friedmann (probably in the 1930s)

Source: Biographical dictionary of those shot and executed (1940-1944) on the French website, Le Maitron

We know that the family had been living in a low-rent building at 2, rue Camille Flammarion, in the 18th district of Paris, since June 1, 1928. To support his family, Bernard Friedmann worked in the hat and cap making trade. This was a very insecure job, and he often found himself out of work, particularly during the 1930s. In the 1920s, he was heavily involved in a major French trade union, the CGTU, and the French Communist Party. He was a militant member of the French labor movement.

Sabina died in 1931, when Ida was only 3 ½ years old. Two years after his wife died, on April 8, 1933, Bernard Friedmann married Blonia Gerszonowicz with whom he already had a daughter, Lucienne, who was born in October 1932. They then had another child, Jacques, on January 13, 1934.

After their mother died, Ida and her brother Maurice, who was born in 1926, were placed in the , Rothschild orphanage at 15 de la rue Lamblardie in the 12th district of Paris. An orphanage register lists the number of children there on January 1, 1943, and reveals that Ida Friedmann was admitted to the home on rue Lamblardie on January 27, 1932. We can only surmise that her father, due to the economic downturn and his involvement in the labor movement, felt unable to provide for his children’s upbringing. The orphanage took in Jewish children who had been orphaned or were estranged from their families. Ida and her brother Maurice, although they were separated in the orphanage, nevertheless managed to see each other in secret.

Ida Friedmann amid the turmoil of war and the German Occupation

When war was declared in September 1939, Ida was still living in the Rothschild orphanage.

After the Germans occupied Paris in June 1940, Ida’s father continued to be active in the French Communist Party, which had been banned in the wake of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, officially known as the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, of August 1939. On June 22, 1941, the pact between Hitler and Stalin was breached when German troops moved into Russian-controlled territory, and the Communists then joined forces with the Resistance and embarked on an armed struggle against the occupying forces. Bernard Friedmann was one such Resistance fighter. On August 8, 1941, he was arrested while handing out leaflets. Sentenced to ten years’ hard labor by the Special Section Court for the Seine department, he was initially detained in the Santé prison in Paris and then transferred to the central prison in Caen, in the Calvados department of France. On December 15, 1941, he was handed over to the Germans, who, in retaliation for the Resistance’s armed operations, took him hostage and shot him.

How did Ida and Maurice find out about their father’s tragic death? We were fortunate enough to make contact with Emmanuelle Friedmann, one of Ida’s nieces, and asked her about this. She told us that Maurice was the first to hear the terrible news, and initially kept it from his sister to avoid upsetting her. He eventually told her in late 1942.

When Bernard Friedmann died, the children from his first marriage were either grown up and living independently, or, like Ida, placed in an orphanage. Only the two children from his second marriage, and Ida’s youngest brother Jean, who was born in 1929, continued to live with Blonia. Charles Friedmann, the oldest of the siblings, who was born in 1911, died on the front during the German offensive in June 1940. Louise was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 70 on March 27, 1944. She was lucky enough to survive and returned to France in 1945. Édouard, born in 1917, was deported on Convoy 47, February 11, 1943, and was most likely murdered soon after he arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Some of the other children, including Jacques and Lucienne, survived the war after being placed with French families, some of them Protestants. French Protestant ministers, who saw what was happening to the Jews, played an important role in keeping them out of harm’s way.

On January 1, 1943, Ida Friedmann was sent to a girls’ home at 9 rue Vauquelin, in the 5th district of Paris. It was one a number of children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews). The Vichy government had founded the UGIF on November 29, 1941, as part of their anti-Semitic policy that began in October 1940. Officially, the UGIF was responsible for assisting Jews in France in their dealings with the authorities and for social welfare, and all Jews were required to join it. However, it also facilitated the identification, surveillance and policing of the Jewish population by both the German authorities and the Vichy regime. It was overseen by the CGQJ (Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, or General Commission for Jewish Affairs), an umbrella organization also founded in 1941.

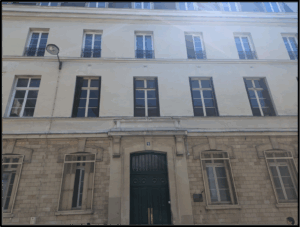

9 rue Vauquelin today

Photograph: DR

We found a little information about Ida’s stay in the Vauquelin home in three reports written by doctors, who were department heads, in February 1943, March 1943 and July 1944 respectively. These suggest that Ida did not have an easy time of it there. At first, she shared a room with her best friend (whose name is not given), but at some point, the friend left. The doctor who wrote the report dated February 22, 1943, recommended that Ida be examined by a psychiatrist, Dr. Eugène Minkowski. He noted that Ida “is very backward, both physically and mentally”, and added that “she is generally quite pleasant, but since her best friend left, she has been prone to fits of convulsive laughter, albeit quite brief, but which [risk] becoming a serious problem if they are not dealt with promptly”. The second report, dated March 16, 1943, was written by Fernand Musnik, the manager of the home, who, in secret, was also a leader of the Eclaireurs Israélites de France, a Jewish Scouts group that was part of the Resistance movement. He wrote: “one of my boarders, the young Irène Friedmann, whose abnormal nervous disposition I have already told you about, refused to go to bed after a series of convulsive fits of laughter. As I tried to take her into her bedroom, she threw herself at me, scratching and biting and screaming so loudly that the whole place was in uproar. We had to hold her down and throw water on her head to calm her down. She also insulted us profusely”.

What do these two reports tell us about Ida? Had she heard that her older brother, Edouard, had been deported to an as yet unknown destination on February 11, 1943? This news, combined with that of her father’s tragic death as well as the broader context of wartime anti-Semitism and the fear of arrests and roundups, must have been very worrying and upsetting for her. Any human being would have felt the same. Anyway, Ida Friedmann stayed on in the Vauquelin home, no doubt in constant fear of being arrested, until July 22, 1944. In a monthly report for the period from June 15 to July 15, 1944, Mrs. Mortier, the manager of the orphanage, recommended that Ida be transferred to the one of the other UGIF homes in La Varenne or Louveciennes, adding that “a stay in the countryside would do her good”. Might this have been in reference to poor nutrition resulting from the food shortages in occupied Paris? Yvette Lévy, who was also deported on Convoy 77 and was staying in the home on rue Vauquelin at the time, later testified that “The fear of being arrested never left us”, and went on: “When we heard about the [Normandy] landings on June 6 [1944], we said to ourselves that it would soon be the end of our ordeal, the beginning of a new life. We really believed it. We danced in the courtyard”. Ida and her friends clearly hoped that Paris would soon be liberated, and they would be freed.

Arrest and deportation

Memorial plaque to commemorate the roundup of July 21-22, 1944 on the building at 9 rue Vauquelin Photo: DR

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, Ida was arrested in the home on rue Vauquelin prior to being deported on Convoy 77. Yvette Lévy, who was arrested at the same time, gave a detailed account of what happened during the roundup, their stay in Drancy and the deportation. The roundup, which was led by Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, took place at five o’clock in the morning of 22 July, 1944. The 33 girls from and the staff of the home did not even have time to get dressed before being taken to Drancy in a tarpaulin-covered truck. Yvette Lévy explained: “We sang all the way to the camp to boost our spirits . We also sang as when we arrived at Drancy camp; we woke everyone up”.

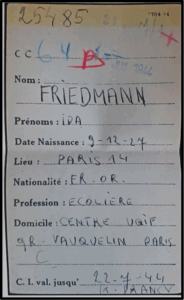

According to her card in the Drancy file, Ida’s registration number was 24,485. A letter “B”, written in red, means that she was “deportable immediately”, so could be put on the next convoy. According to this card, she was assigned to room 4 of staircase 6. Meanwhile, the Drancy camp transfer log states that Ida Friedmann was put in room 1 on staircase 7 (she may well have been moved to another room). Yvette Lévy (who, according to the same logbook, was in the same room) said: “For three days we remained in our nightgowns; it was the manager of the home, Mrs. Mortier, who went back to get our things. As she had no suitcases or backpacks, she bundled our things up in sheets”.

Ida Friedmann’s record card from Drancy camp

Source: French National archives in Pierrefitte, ref. F9 5743 262025 L

Ida Friedmann spent ten days in Drancy, at the height of summer, sleeping on wooden bunks with straw mattresses crawling with bedbugs, with no access to water or toilets. Yvette Lévy added: “It was hell. Aloïs Brunner forbade the children to go down into the courtyard to run around and unwind. He didn’t want to see them laughing, and he didn’t want to see them crying either. The children got sick from the food. We helped the supervisors look after the little ones, and to kill time, we had them sing”.

On July 28, the camp was buzzing with rumors that a transfer to Germany was imminent. Ida must have gotten wind of it. We can just picture her, along with the other “deportable” internees, worrying about where they were going and what was to become of them. The rumors in Drancy were about a place they called Pitchipoï, which was a made-up name for an imaginary place in the middle of nowhere, or the back of beyond.

Two days before the convoy was due to leave, the people whose names were on the deportation list were moved into designated rooms on a staircase nearer to the main gate. Families and couples were reunited. However, they were no longer allowed to have any contact with the other internees in the camp.

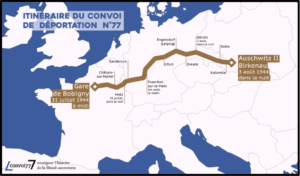

On July 31, 1944, it was time to go. The deportees were taken by bus from Drancy to the nearby Bobigny station, where Aloïs Brunner had arranged for enough cattle cars to be waiting for them. Ida was one of 324 children on the convoy, alongside 986 adult men and women. They were then loaded onto the train, with around sixty people crammed into each wagon. The travelling conditions were appalling, and again, Yvette Lévy’s testimony is a valuable source of information: “It was impossible for everyone to sit down: half of us sat and the other half sat on our girlfriends’ laps. We switched places every 10 minutes or so. In each car there was one bucket of drinking water and another bucket for our bodily needs. There were enough cans of Nestlé sweetened condensed milk for the children, but no water to make up bottles. We were sweltering in the heat, the little ones were parched with thirst, and so were we. As the journey wore on, the bucket filled up with our excrement, and as the train braked, it eventually overflowed. From then on, we could not sit down, the floor was all wet and oh, the stench! When we reached the border at Novéant (near Metz), the driver and engineer got off the train. The Germans then took over and we kept going non-stop, day and night”.

The route taken by Convoy 77 (July 31 to August 3, 1944)

Source: Convoy 77 website

Convoy 77 arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau during the night of August 3, 1944. As soon as the deportees got off the train, the selection process began. 836 people, including all the elderly people and the children were sent straight to the gas chambers. Ida Friedmann, however, was selected to go into the camp to work, together with 182 women and 291 men. She had to endure all the humiliating camp admission procedures and it would not have been long before she heard what had happened to the majority of the other people who were on the convoy.

She spent three months in Auschwitz and then, on October 27, 1944, she and a number of other young women from Convoy 77, including Yvette Levy, were transferred to Kratzau, a forced labor camp based in an abandoned textile factory to the northeast of Prague in the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia, in what is now the Czech Republic. The camp held both Jewish deportees and Polish prisoners of war, who were housed in separate barracks. Anna Sussmann and Lilli Ségal, two other women from Convoy 77, escaped from Kratzau in late November 1944 and made their way to Switzerland. In January 1945, they managed to relay first-hand accounts of conditions in the camps.

When they arrived in Kratzau, the women were crammed into dormitories, where there was absolutely no privacy. The French and Hungarian women were assigned to the second floor of the building. They only left the dormitories in groups for meals, to wash and to work in the factory. The work involved making and dyeing clothes, using toxic products such as lead, which can have serious adverse effects on the respiratory system. There was a 9:00 p.m. curfew for everyone except the women who worked the night shift, for whom conditions were even worse. The day shift workers had little food, and the night workers got even less. The meals were poor; lunch was a cup of soup or broth and a piece of bread, while in the evening, it was a small portion of potatoes or beetroot, and occasionally a little meat and onions. The quantity of food was nowhere near enough for working women. The combination of insufficient food and poor hygiene led to high mortality rates from infectious diseases spread by lice (typhus, dysentery, scabies, etc.). Not only that, but some of the prisoners died of cold and fatigue as a result of working in the factory. They had to walk for about an hour to get to the factory before 6:00 a.m., and then walk back again after twelve hours’ work, arriving back at the camp at around 7:00 p.m. They did this seven days a week, whatever the weather. There was no medication available for the prisoners, and no way of caring for them when they were sick. The sanitary conditions were awful: there was no soap or detergent, no change of clothes, just one thin tunic each, which meant they were permanently cold and dirty. Even getting water was an ordeal. Here is an extract from Anna Sussmann and Lilli Ségal’s account: “The only two taps in the building where we slept were for camp staff only, and we were strictly forbidden to use the water”. Every day, the women were physically and verbally humiliated by the camp supervisors, who were replaced if they were too sympathetic towards the prisoners. The Polish and Russian prisoners of meanwhile, who were held separately from the Jewish women, had slightly better accommodation and food and were generally better treated. Yvette Levy’s testimony is very similar to that of Anna Sussmann and Lilli Ségal, although she added that some of the male prisoners helped the women occasionally. For example, a Czech man gave Yvette Lévy a piece of bread, which she shared with five other women. Ida Friedmann must have suffered the same hardships. She was held in Kratzau for over nine months until the Red Army liberated the camp on May 9, 1945. She was repatriated to France via the Longuyon reception center, near the Belgian border, on May 20, 1945, and was then admitted to the Cochin hospital in Paris. Of all the people deported on Convoy 77, only 157 women and 93 men survived. Despite what she went through, Ida Friedmann was very lucky to be among them.

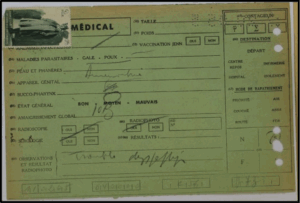

Ida Friedmann’s medical card, issued when she returned from the Kratzau camp in May 1945

Source: French Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier 21 P 609 389

Life after her return from the camps

There is very little information available about what happened to Ida Friedmann after she returned to France. Even family members who survived the Holocaust, and their descendants, know very little about her life. She chose not to share her story with her family and appears to have distanced herself from them after the war, not wanting to talk about her time in the camps. Recounting such a traumatic experience cannot have been easy.

Her brother Maurice met her soon after she was repatriated from Kratzau. His account was passed on to us by Emmanuelle Friedmann, Jacques Friedmann’s daughter (i.e. Ida and Maurice’s niece), whom we were privileged to be able to meet during our investigation. This is what he had to say: “There she was, at last! I hardly recognized her, she was just a skeleton, as the nurses took her up the stairs on a stretcher. But yes, it was my sister Ida, with her shaven head and so thin – my long-awaited little sister! It was in the Cochin hospital in Paris; I had been told that she had come home while I was in the nearby Val de Grâce hospital, where I had been receiving treatment for several months… it was the son of my wartime “godmother” ( Mrs. Cordonier) who had been searching for her. God knows this wasn’t the only case, as so many families were hoping for the safe arrival of one of their own from the camps”.

According to records held by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, Ida became a ward of the State in the Tarn-et-Garonne department of France. She is also listed in the register of the orphanage in Moissac, in the Tarn-et-Garonne department, where she arrived on July 6, 1945. The home was founded during the war by Edouard (Bouli) Simon and his wife Shatta (Charlotte Hirsch), on the initiative of Robert Gamzon, leader of the French Jewish Scouts movement. It secretly took in a large number of Jewish children, orphans of various nationalities and backgrounds. During the round-ups, the youngsters were hidden by families in the surrounding villages, and some even fled via Spain to other countries or joined the Resistance. In 1945, the home in Moissac remained open and took in young survivors from the concentration camps. It remained in operation until 1953.

After she left Moissac, Ida Friedmann is mentioned in several records, including a file on her application for “political deportee” status, held by the French Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War at the Caen Memorial in Normandy. Emmanuelle Friedmann, Ida’s niece, shared some additional details with us during a moving meeting at our high school on January 15, 2024. At the time Ida applied for a political deportee card in November 1950, she was single, working as a typist and living at 64, rue de Montreuil in Versailles. In August 1961, she declared that she had lost her political deportee card and stated that she lived at 48, avenue Henri Barbusse in Bondy. She was issued with a new card on October 18, 1961, which enabled her to continue receiving an allowance for political deportees and internees of 12,000 francs a month (equivalent to around $250 today)

Ida Friedmann moved to the south of France sometime in the 1960s. She lived in La Seyne-sur-Mer, where she married Maurice Émile Lamant on July 11, 1970. The couple divorced on February 25, 1987.

As far as we know, Ida did not keep in touch with many of her family members, and family gatherings were rare. Why might this have been? Of her numerous siblings, two brothers died during the war and one sister was deported but returned from the camps. Jacques and Lucienne, Ida’s youngest brother and sister, from Bernard Friedmann’s second marriage to Blonia Gerszonowicz, were living with their mother on rue Camille Flammarion in Paris in 1945. Emmanuelle Friedmann, Jacques’ daughter, does know however that Ida remained very close to and continued to see her brother Maurice, who died in 2008.

Ida also seems to have cherished the memory of her father. She was a member of the French National Association of Families and Friends of Murdered and Massacred Members of the French Resistance. Founded soon after the Liberation, this organization initially set out to help families whose loved ones had been shot as hostages or Resistance fighters during the Occupation. Its work included research and lobbying government bodies.

Over time, the need for practical support diminished, so these days the organization is more involved in memorial work, keeping alive the memory of Resistance fighters and hostages who fell victim to German repression during the Occupation. It also campaigns against fascist-based ideology, Holocaust denial, xenophobia and all types of racism. In 2007, the Friedmann family, including Emmanuelle Friedmann, gathered in Paris to remember Bernard Friedmann. Emmanuelle kindly shared with us part of Ida’s poignant speech that day: “To come back to my father, believe me, I’ve never forgotten him, because I must tell you that he regularly […] came to visit me in the orphanage, even during wartime. I knew nothing of his political activity or his involvement in the Resistance, that goes without saying. But I’ll never forget how, during his visits in 1941, he used to hold me tight as I sat on his lap. He must have had a premonition about how he would meet his tragic end!”

Ida died on October 8, 2015, at the age of 87, in La Valette-du-Var, in the Var department of France.

Conclusion

By exploring Ida Friedman’s life story based on limited sources and fragmented documentation, we were able to delve into the very depths of the Holocaust and its aftermath, to look beyond the numbers and grasp the impact of the 20th century’s most devastating genocide on one individual, her family and the people around her. It is our duty, as the next generation, to remember and pay tribute to these extraordinary people who lived through such a horrific episode in human history; those who fell victim to it, and those who, more often than not, never came back. Each and every Holocaust victim has his or her own story, yet many of them will never be told, erased by the passage of time.

As a result, many of the victims’ descendants have little or no information about their family’s background or where they came from. How can anyone build their future without first knowing about their past?

Emmanuelle Friedmann, Ida Friedmann’s niece, whom we were fortunate enough to meet, and who shared some of her family’s personal documentation with us, told us that she regretted knowing so little about her roots; that she had not taken more interest in her aunt’s past during her lifetime; that she had not asked her more questions.

Sources and bibliography:

Witness testimonies:

Emmanuelle Friedmann, Ida Friedmann’s niece, given on January 15, 2025 in Gif-sur-Yvette. Yvette Lévy, telephone conversation in December 2024 and testimony online on the Convoy 77 website.

Archives:

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. File on Ida Irène Friedmann, N° 21 P 609 389.

- Drancy files, individual records, entry and exit register. Kept at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

- YIVO archives, Institute for Jewish Research RG 210-46: UGIF archives, Vauquelin center.

- CHÂTEAUBRIANT, Journal de l’Association Nationale des Familles de Fusillés et Massacrés de la Résistance Française et de leur Amis, N° 255, 4th trimester, 31 December 2015.

- French Ministry of the Armies in Vincennes. Dossier on Bernard Friedmann, N° 16P 235476.

Websites and bibliography:

- https://fusilles-40-44.maitron.fr: Le Maitron, biographical dictionary, people shot (1940-1944).

- https://convoi77.org: How to read the Drancy files?

- http://www.cercleshoah.org/spip.php?article705: Anna Sussmann and Lilli Segal’s testimonies about their experience in the Weißkirchen-Kratzau camp

Thanks:

Our warmest thanks to Emmanuelle Friedmann for the information she kindly provided about her family. Working on history offers the opportunity to meet new and interesting people…

We would also like to thank Corinne Rachel Kalifa, General Secretary of the French National Council for the Memory of Deported Jewish Children, for the information she provided on the Rothschild orphanage on rue Lamblardie.

Lastly, our special thanks go to the Convoy 77 team for their advice and the documentation they provided during the project.

An afternoon spent following in Ida Friedmann’s footsteps in Paris during the Occupation

The “Field trip guide” that was produced for students who went to Paris as part of the “Convoy 77” project on Wednesday, April 30, 2025.

Objectives of the visit:

The aim of the field trip is to go on a “remembrance walk” in Paris, to see some of the places where Ida Friedmann lived during the German Occupation, from June 1940 until she was deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. We will also take a “memorial stroll” through some of the most symbolic sites of “German-era” Paris. Lastly, we aim to enjoy our time together and remember that the past not only leaves its mark on the present, but also helps us to better understand life in France today.

The purpose of this guide is to prepare you for the field trip. In it, you can read about the key places we will be visiting as well as some historical background information and practical tips.

Practical information:

We will meet in front of the school’s Gif building (on the Courcelles station side) as soon as possible after morning classes. We will then take the RER train to Paris. The “memorial trail” will take around 3 hours in all. Most of the route will be explored on foot (7 or 8 km), and some of it by subway. We should be back in Courcelles by 6:00 pm. Please wear good walking shoes, and bring some water. A camera (if your smartphone does not take good photos) would be a good idea too, in order to “document” the experience.

The route:

We will get off the RER train at the Luxembourg station, and head for the former girls’ home on rue Vauquelin. From there, we will embark on a long walk to the Strasbourg-Saint Denis subway station. The main points of interest along the way will be:

- The UGIF home at 9 rue Vauquelin. It was here that the Germans arrested Ida Friedmann on the night of July 21-22, 1944, after which she was transferred to Drancy and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau from the Bobigny railway station by Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

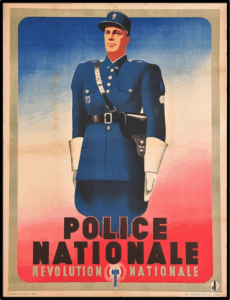

A police recruitment poster (1942)

- The Paris Police Headquarters on the Ile de la Cité, which was the main law enforcement center in the Seine department during the Occupation, for both the Germans and the Vichy government. The Paris police actively collaborated with the occupying forces in two ways. Firstly, they hunted down Jews in the Seine department, in particular during the Vel d’Hiv’ roundup on July 16 and 17, 1942 (but not only that: they made numerous arrests and carried out roundups throughout the Occupation, sometimes on the basis of anonymous tip-offs). Secondly, they tracked down members of the Resistance, particularly the Communist resistance, which had been engaged in an armed campaign since the summer of 1941. The Police Headquarters’ Special Brigades specialized in tracking down, arresting and interrogating (and torturing) resistance groups in the Paris area. It was they who dismantled the “Manouchian group” in October-November 1943, then handed them over to the Germans, who shot them at Mont Valérien in February 1944. This collaboration lasted from October 1940 to the Liberation of Paris (August 18 to 25, 1944), although over time, some police officers joined the Resistance or became less and less willing to obey orders.

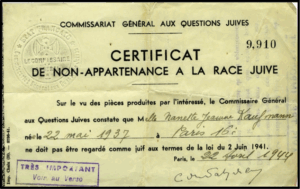

A “Certificate of non-membership of the Jewish race” issued by the Jewish Affairs Committee, April 1944

- The headquarters of the CGQJ (Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives or Jewish Affairs Committee) at 1 place des Petits Pères. The CGQJ was founded in March 1941 to enforce the October 1940 decree on the Status of the Jews and to arrange for the “Aryanization” of Jewish property, as well as the dissemination of anti-Semitic propaganda throughout occupied France. The CGQJ oversaw the work of the PQJ (Police aux Questions Juives, or Jewish police), which was set up in October 1941 and played an active role alongside police officers from the Police Headquarters in the various roundups organized in the Seine department during the Occupation. The PQJ was made up of very enthusiastic collaborators, all of whom were manifestly anti-Semitic and, at the time of the roundups, had no hesitation in robbing Jewish victims or looting the apartments of people who had been arrested and sent to Drancy. The CGQJ was also responsible for providing “certificates of non-membership of the Jewish race”, which could only be issued after a visit to a physician sworn in by the CGQJ. Such a certificate was issued, for example, if an employer had reservations about hiring someone.

The Meurice hotel in 1942. Photo: DR

- The Meurice hotel, at 228 rue de Rivoli. During the Occupation, the building was used as the headquarters of the German command center for the Paris garrison, as well as accommodation for a succession of German military governors.

The Paris Kommandantur during the Occupation. Photo: DR

- The Banque Nationale de Paris building, on the corner of avenue de l’Opéra and rue du 4 September. During the Occupation, this building was the headquarters of the Paris Kommandantur. The offices of the German military command in Paris and the Seine department were based there.

“The Jew and France” exhibition in Paris, in September 1941. Photo: DR

- The Berlitz Palace (Hanover Palace) on the corner of rue du 4 September and the boulevard des Italiens. Between September 5, 1941 and January 15, 1942, this Art-Deco building, which was built in 1932, hosted an exhibition on “The Jew and France”, sponsored by the IEQJ (Institut d’Étude des Questions Juive or Institute for the Study of Jewish Issues), an French anti-Semitic group founded in May 1941 and funded by the occupying forces. The “crème de la crème” of the contemporary collaboration community, as well as ordinary French citizens, flocked to the exhibition (some 155,000 visitors in all). The aim of the Germans and their collaborators in organizing this exhibition was to pave the way for the “Final Solution” in France. It had begun in the summer of 1941 on the Eastern Front. It was also to spread Nazi propaganda against “Judeo-Bolshevism” in France, at a time when Germany had been at war with the Soviet Union since June 22, 1941.

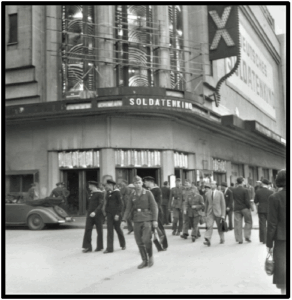

The Rex cinema in 1942. Photo: DR

German soldiers outside the Rex. Photo: DR

- The Grand Rex movie theater on boulevard Poissonnière. Built in 1932, together with the Gaumont Palace cinema on Place de Clichy, this was the largest movie theater in Paris (it could seat over 3,000 people). During the Occupation, it was commandeered by the German authorities to become a “Soldatenkino”, a cinema used to entertain off-duty German soldiers. On September 17, 1942, a resistance group organized an armed attack on the cinema, killing three German soldiers and wounding sixteen others. In retaliation, the Germans shot 70 hostages in Bordeaux, in the Gironde department of France and a further 46 at Mont Valérien, in Suresmes, on the outskirts of Paris. The occupying forces drew up lists of hostages from among prisoners arrested for “communist propaganda” and/or because they were Jewish. Ida’s father, Bernard, was one of them, and was killed in December 1941. Far from destabilizing the armed resistance movement, such repressive measures actually intensified it. As of December 1941, the public overwhelmingly opposed the occupying forces’ large-scale retaliation. In 1943, the “hostage policy”, as the Germans called it, was suspended and people were instead deported to concentration camps in the Reich. However, large numbers of Resistance fighters continued to be shot right up until the Liberation in the summer of 1944.

From there, we will go to the Strasbourg-Saint Denis subway station (a 5-minute walk away) and take line 4 to Porte de Clignancourt station. From there, we will head to 18 rue Camille Flammarion, where the Friedmann family have lived from 1931 onwards. The building is typical of the Habitations à Bon Marché (low-cost housing developments) built in the 1920s and 1930s on the site of the former Paris fortifications (also known as the “enceinte de Thiers”), which were demolished shortly after the 1914-1918 war.

After that, it will be time to think about heading home. We will return to the Porte de Clignancourt subway station and take line 4 towards Bagneux-Lucie Aubrac [named after a well-known female resistance fighter]. Will we change at Gare du Nord and take the RER train, line B, towards Saint Rémy lès Chevreuse.

Français

Français Polski

Polski