Israel (Henri) KRENGEL

This biography was written by students from the Maria Konopnicka High School in Włocławek, Poland.

Chapter 1: Dobrzyń – Israel’s hometown

Dobrzyń is a delightful town that stretches along the Vistula River, between golden fields and green forests. On the hill there is a cross that marks the former site of a Teutonic castle, which was destroyed in a fire in 1767.

Historical sources show that Jewish settlement in the town of Dobrzyń began in the 14th century. The oldest document dates from 1507. The earliest references thus appeared in documents from the 16th century. These include the privilege of King Zygmunt I, granted on March 5, 1519, which was of great importance for the economic development of the city. The town was granted the right to hold three fairs per year and a weekly fair on Tuesdays. It was around this time that the Jews first appeared in Dobrzyń.

At its peak, in 1808, the Jewish population accounted for 83.2% of the inhabitants.

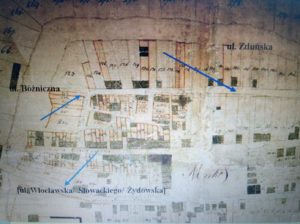

A segment of a copy of the Dobrzyń city map dating from 1804. Source: Central Historical Archives of Warsaw. Map collection, reference number 524-6. [1] Ms. Agnieszka Witkowska’s Bachelor’s thesis.

Today, the town is home to 2117 people (2019 data, Wikipedia). In 1897, when Israel Krengel was 4 years old, Dobrzyń had 2,485 inhabitants, 927 of whom were Jewish (37.3% of the population).

In 1939, of 3,268 people, about 850, or 26%, were Jewish. In the years 1930-1938, more than 200 births were registered to Jewish families. During this period, more than 70 marriages were concluded. [1] Data from Agnieszka Witkowska’s Bachelor’s thesis.

The Jewish population played a very important role in the social, political and economic life of the city. There were Jewish political parties as well as educational, cultural and religious organizations and enterprises. Representatives of the community participated in elections to the city council in 1918, 1919, 1922 and 1927. The municipality also had a synagogue, a prayer house, a cemetery, a mikveh (bathhouse), a ritual slaughterhouse, school facilities, a library, a branch of the Makabi sports club and residential quarters. The town was, however, one of the poorest in the Pomeranian Voivodeship.

Local residents recall, “Yes, before the war, there were Jews living here, yes, Słowackiego [street], or perhaps it was Mickiewicza [street], was once called Żydowska [street] (meaning Jewish street), the synagogue was where the police station is now, and the Jewish cemetery was flooded when the dam was built.”

We managed to find out that Żydowska street was another name for Słowacki street. Before the war, the Krengel family house, where Israel and his four brothers and one sister lived with their parents, was number 14.

Only 200 meters away, on Bożniczna street (now Zduńska street), was a synagogue where Israel’s parents and grandparents were married. It was built in the late 18th or early 19th century. In his book Kujawsko-dobrzyńscy Żydzi w latach 1918-1950, Tomasz Kawski writes: “It was made of wood, oriented towards Jerusalem in the traditional manner, and featured a longitudinal layout, i.e., a men’s hall was preceded by a smaller hall, and on the second floor there was a women’s area (women were separated from men).”

The synagogue at Dobrzyń nad Wisłą. Source: http://www.jpreisler.com/Dobrzyn.htm

The interior of Dobrzyń synagogue. Source: https://www.facebook.com/ftdepths/posts/the-synagogue-in-dobrzyn-nad-wisla-where-jonnys-family-once-prayed/930233177040338

Nearby, there was a cemetery that was probably founded in 1557.

A fragment of matzevah from the collection at the Dobrzyń Museum in Dobrzyń nad Wisłą.

“A young scientist is buried here.” Translation and photo: Agnieszka Witkowska

Dobrzyń figured prominently in the minds of German historians and politicians due to the arrival of the Teutonic Knights in this area in the 13th century. Long before the outbreak of World War II, plans were already being made to turn the city into a garrison town. The Teutonic Knights were German, and founding a garrison here was a reference to the previous German presence in the town.

In her Bachelor’s thesis Agnieszka Witkowska writes: “At the beginning of September 1939, German army troops entered Dobrzyń. A month later, the Jewish population was ordered to leave the town. They were probably moved in groups to Kutno, Włocławek and Żychlin, and placed in local ghettos.” According to Mirosław Krajewski, the author of the book Byli z ojczyzny mojej, part of the Jewish population of Dobrzyń was taken to the barracks in Bydgoszcz and then shot at Tryszczyna or at Rynków, near Bydgoszcz.

On September 24, German troops set fire to the synagogue in Dobrzyń, to a study center called Beit midrash and to the headquarters of the Hasidim in Gur, which was burned down. The Jewish population was expelled from the city in the first few days of October 1939. Rabbi Josek Wolf Sender was the last person to leave Dobrzyń.

In the years that followed, the Germans demolished many of the Jewish houses, including the one that we are interested in, on Słowackiego street.

In Dobrzyń, the Jews were persecuted in a number of ways. Under seemingly innocuous pretenses, taxes were imposed on them, their houses, businesses and stores were looted, and from early October, the occupying authorities’ requirement that the Jewish population wear yellow stars was strictly enforced. In the second half of October 1939, the slaughter of the Jewish population began. “Of the Jews, those who died were mostly those against whom the local Germans made complaints or remarks. In many cases, Jews were killed because someone wanted to rob them or seize their property. The situation there was no different from that in other cities in occupied countries. To show the extent of the repression, I refer to the HEYDRICH report of November 11, 1939, which describes the arrest of 20,000 Jews, the burning of 191 synagogues and the demolition and looting of 815 stores.” (Mirosław Krajewski, Byli Ojczyzny mojej, p. 12)

An estimated Jewish 25 people survived the war. Some of them never returned to the town. In June 1945, two Jews were listed, and in 1946, there were six. By 1947, all the Jews had left the town without a trace. The same thing happened in neighboring towns and villages, such as Włocławek.

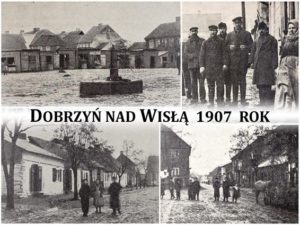

During our research, we found some photos on the Internet of Dobrzyń in 1907. At that time, Israel was 14 years old and all of his brothers and sister had been born by then. Their father worked as a butcher and their mother took care of the house. Besides Israel, there were Josef (16), Icek (9), Chana (6) and Zelik (4). The youngest, Mojsze, was only one year old.

What kind of family was it? Like many others, pretty poor! The town, also like many others, was pleasantly located on the left bank of the Vistula River. There was a church, a synagogue, a few stores, an inn and a market where both Polish and Yiddish were spoken.

We do not know exactly when Israel left the family home. We can only assume that it was poverty that prompted him to emigrate. We do not know why he chose France as his new home. Might he have had a relative there? One way or another, Israel, Icek, Zelik and Chana were all living in Paris before the war.

We also do not know if the parents witnessed the start of the war. Enoch would have been 76 years old then. However, we did find documents that confirm that in 1939, Mojsze, the youngest of the brothers, was still living in the family home.

Oliwia Wiśniewska, I E

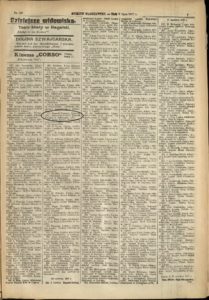

List of companies active in Dobrzyń nad Wisłą in 1917. Among the business people listed was Henoch Krengel, a butcher.

Warsaw Courrier, July 9, 1917.

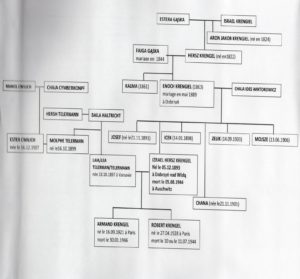

Chapter 2: The family

Well-preserved records have helped us considerably in reconstructing the Krengel family tree. However, the documents drawn up by the rabbis and the records of the Nazi occupiers were destroyed when the German troops retreated.

With the help of two visits to the State Archives, we were able to piece together Israel Krengel’s family. Around 1800, when Poland was partitioned, Dobrzyń was included in the Prussian part. It was during this period that Israel’s great-grandfather, who was also called Israel, and Estera Gąska, his future wife, were born. The couple had at least two children.

The town was also within the borders of the Duchy of Warsaw.

In 1822, their son Hersz (Israel’s grandfather) was born, followed four years later by his brother, Aron Jakob. In 1844, Hersz married Fajga Gąska. They had at least two children, an older son, Kalma, born in 1861 and Enoch (Henoch), the father of our Israel, born in 1863. Both boys were born in Dobrzyń.

In the same town, in May 1889, Enoch, aged 26, married Chaja Ides Wiktorowicz, who was 24.

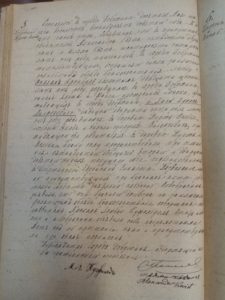

The marriage certificate of Israel’s parents, Enoch and Chaia Ides. Dobrzyń, May 1889.

Their first son, Josef, was born on November 21, 1891. Two years later, on December 5, 1893, at about six in the morning, Israel Hersz Krengel was born.

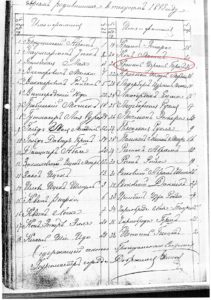

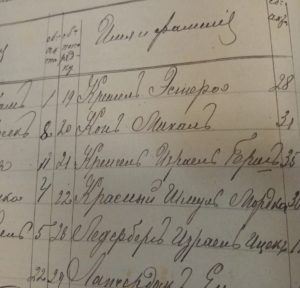

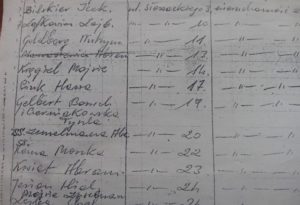

Jewish registers. Source: State Archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch.

The register of children born in 1893 includes the name Israel Hersz Krengel.

The inscription in the register. Source: State Archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch

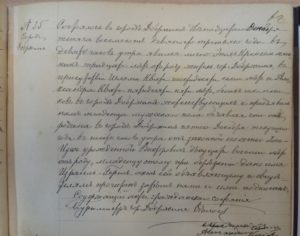

Israel’s birth certificate. Jewish register. Source: State Archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch.

Israel’s birth certificate – Polish translation

Next, on January 14, 1898, their third son, Icek, was born, followed by Chana, the only daughter of the Krengel family, on November 21, 1901, then two years later Zelik, on September 14, 1903, and lastly Mojsze, their youngest son, on June 13, 1906.

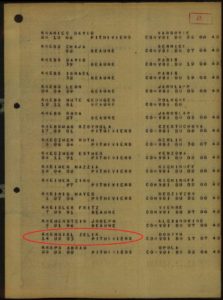

The family led a quiet and fairly simple life. They were tailors. In the list published on July 9, 1917 in the Kurier Warszawski newspaper, Enoch is also included, as a butcher. Perhaps either poverty or antisemitism prompted the older brothers to emigrate to France. No anti-Semitic acts were recorded in the town, but as in most European countries at that time, anti-Semitism was rife. Most likely, the two older brothers left together. This must have happened before 1919. Israel’s younger brother, Icek, also ended up in France. During the war he was arrested and deported on the first convoy to Auschwitz-Birkenau. We know that he was married to Berta, born in 1898. Her maiden name was Liberman. He died at the age of 44 on March 27, 1942. A similar fate befell Israel’s younger brother, Zelik, who also lived in France. He was deported from Pithiviers to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he died in 1942.

List confirming that Israel’s brother Zelik was deported

Mojsze, Israel’s youngest brother, stayed in Poland. He lived in Dobrzyń, at 14 Słowackiego street, as did his father and grandfather.

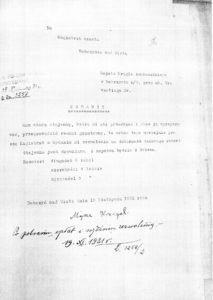

Une l A letter from Mojsze Krengel to the Dobrzyń town hall, dated November 19, 1931, applying to carry out renovation works.

On June 9, 1932, Mojsze married Małka Liba (née Goldberg), who was born in 1907. The wedding took place in his hometown, Dobrzyń nad Wisłą.

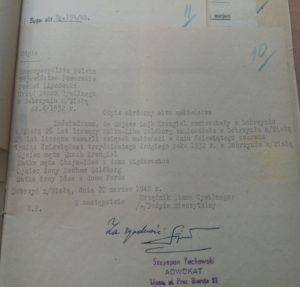

Marriage certificate of Israel’s youngest brother, Mojsze, and Małka Liba Goldberg, in1932

Transcription dated 1948. Source: State Archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch

In the course of our research, we discovered that in 1939 Mojsze was still living in Dobrzyń on Słowackiego street, also known as Żydowska street (meaning Jewish street). The couple did not have any children and their happiness did not last long. About ten years later, in the early days of the war, they were removed and transported to the ghetto in Skarżysko Kamienna, where Mojsze died on May 14, 1942, and Małka on December 27, 1942.

Notes from the Municipal Office in Dobrzyń nad Wisłą confirming that the last owner of the house at number 14 Słowackiego street was Mojsze Krengel

The house that stands today at 14 Słowackiego street, where the Krengel family lived.

Photo, May 2020 – Dariusz Łoboda

Chana, who was Enoch’s only daughter and thus the only sister among 5 brothers, was the only child to survive the war. It is not known how long she remained in Dobrzyń. She probably left Poland before the war. What is certain is that she was in France in 1948. At that time she lived at 21, Faubourg Saint-Denis, from where she wrote to the court in Lipno about her parents’ estate and the house on Słowackiego street.

Letter from Chana to the court in Lipno, dated 1948. Source: State Archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch

Justyna Mikołajewska, I E

Chapter 3: Israel’s time in France

It is unclear exactly when Israel came to France. It must have been before October 14, 1919, because it was then that he married Laya Tallermann (also spelled Tellerman or Tellermann), who was 22 years old, was born in Warsaw and lived with her parents in the French capital. Israel was a tailor and his wife a seamstress. Two years later, on September 16, their first son, Armand, was born. The second son, Robert, was born seven years later, on April 27, 1928. The couple applied for French nationality, which was granted in October 1929.

Copy of Israel and Leya’s marriage certificate, dated October 14, 1919

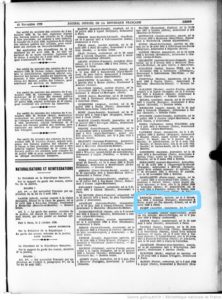

Confirmation of that Israel was granted French citizenship. Official Journal of the French Republic, dated November 10, 1929

In France, Israel assumed the name Henri and Laya used the name Léa. The family decided to escape to the free zone, and moved to Lyon. It was there, in July 1944, that one of the most tragic moments in the family’s life would unfold.

Israel worked as a tailor in Lyon, and his youngest son helped him.

On July 3, four men from the Parti Populaire Français (French Popular Party) came to Israel’s store and stole 15,000 francs. They interrogated and beat 16-year-old Robert. They were held until July 10 or 11 at the Edelweiss Hotel on rue Massène, as was confirmed by people who witnessed the arrest.

Both father and son were taken by car to the Gestapo headquarters on Place Bellecour.

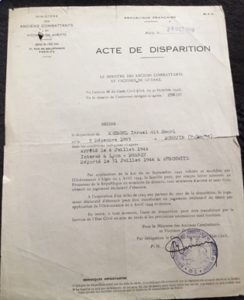

That same day (July 10 or 11, 1944) Israel was sent to Fort Montluc prison, then taken from there to Drancy camp before being deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. According to a certificate, Robert had died.

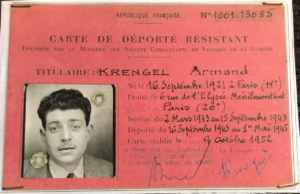

We also discovered that Armand had joined the Resistance in Lyon. On one of the documents, in the column “role” it says “anti-German propaganda”.

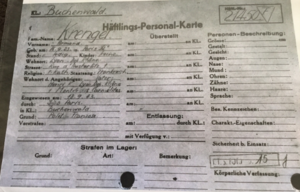

In 1946, while searching for her son, Lea Krengel wrote in one of the documents in the column “number of children who survived”: 1. This proves that Armand survived the war. We found out that Armand was detained in Germany, in the Buchenwald camp. He was arrested in 1943 while trying to cross the Spanish border.

We have also established that Armand survived the war. He died on January 30, 1966, at the age of 44. Three years earlier, in 1963, he received the Order of the Knight of the Legion of Honor.

In 1948, Lea applied to have Israel recognized as having “Died for France”. This was granted on January 29th of the same year.

Marta Jasińska and Nina Bogalecka, II B

Chapter 4: Timeline

- 1800 (approx.) – Birth of Israel Krengel, our Israel’s great-grandfather

- 1800 (approx.) – Birth of Estera Gąska, his great grandmother. They had at least two sons

- 1822 – Birth of first son – Hersz Krengel (Israel’s grandfather)

- 1826 – Birth of second son – Aron Jakob Krengel

- 1844 – Hersz married Fajga Gąska. They had at least two children

- 1861 – Birth of first son – Kalma

- 1863 – Birth of second son, Enoch (Israel’s father)

- 1889 – In May, in Dobrzyń, Enoch married Chaja Ides Wiktorowicz. They had six children:

- 1891.11.21 – Birth of son Josef – the first child

- 1893.12.05 – a 6am, Israel Hersz Krengel, our key figure, was born – the second child

- 1898.01.14 – Birth of Icek – the third child

- 1901.11.21 – Birth of Chana – the fourth child

- 1903.09.14 – Birth of Zelik – the fifth child

- 1906.06.13 – Birth of Mojsze – the sixth child

- 1919.10.14 – Israel married Laia (Laya, Léa) Talermann in Paris

- 1921.09.16 – Birth of Israel and Laya’s first son – Armand (died on 30.01.1966)

- 1928.04.27 – Birth of Israel and Laya’s second son – Robert (died in 1944 in Lyon)

- 1929.10.22 – Israel acquired French nationality

- 1929.10 – Léa, née Telermann, became a French citizen

- 1931.11.19 – the Krengl family (including Mojsze) were still living in Dobrzyń

- 1932.06.09 – Mojsze married Małka-Liba Goldberg

- 1939 – the family was still living at 14 Słowackiego street

- 1942.05.14 – Mojsze Krengel died in the ghetto at Skarżysko Kamienna

- 1942.12.27 – Małka-Liba, Mojsze’s wife, died in the ghetto at Skarżysko Kamienna

- 1944.07.03 – 4 men burst into Israe’ls store in Lyon. 15,000 francs were stolen

- 1944.07.04 – Israel and Robert ran into one of the men in the street. They were arrested and detained in the Edelweis Hotel until July 10 or 11

- 1944.07.10 – Israel and Robert were taken to the Gestapo headquarters on the Place Bellecour. Robert tried to escape. Shots were fired. This was probably where Robert died

- 1944.07.11 – Israel was transferred to Fort Montluc, from there to Drancy, and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77

- 1944.08.05 – The official date of on which Israel died

- 1946 – In document 304BC11, Léa Krengel wrote under the heading “Number of children who survived”: 1, which means that Armand survived

- 1948 – Léa received a document confirming that her husband had died. She applied to have him recognized as having “Died for France” (granted on January 29, 1948) and as a Political Deportee (granted on May 5, 1953

- 1948.03.20 – The family house at 14 Słowackiego street was included in the list of abandoned properties, post the German occupation. It was handed over to the Dobrzyń town council in December 1945

- 1948.06.22 – Chana cited the sources found when she tried to reclaim her parents’ house. She referred to herself as the sole heiress, which suggests that her brothers did not survive. She was living at 21 Faubourg Saint Denis in Paris and still using the surname Krengel

- 1966.01.30 – Death of Armand Krengel, Israel’s first son

Krengel family tree

Chapter 5: Epilog

When we were close to completing our project, we managed to trace and contact Israel Krengel’s granddaughter, Dominique Krengel. Thanks to her, we were able to collect more information about the fate of her ancestors and, more importantly, she provided a lot of valuable information and shared some family mementos. Among the documents and photos, there was … the photo of Israel Krengel!

We are most grateful to you, Ms Krengel, for this valuable contribution. We were able to reconstruct Israel’s family tree, find the location of his house, find various and sometimes surprising documents, and thanks to you we were able to see his face, his bright eyes and his shy smile. Thank you.

Henri and Laya in their youth, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

In the foreground, Henri and his parents-in-law, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

Laya, her mother and Armand in a cart, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

Missing person certificate for Henri Krengel (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

Deported Resistance fighter card in the name of Armand, Henri’s son, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

Armand’s record card from Buchenwald, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

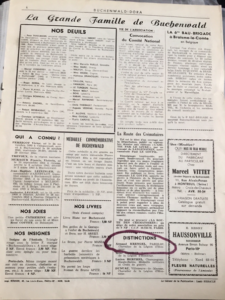

Armand’s Distinction, published in “Le journal de Buchenwald-Dora”, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

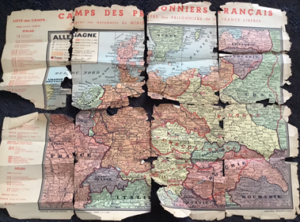

Map of camps for French prisoners, found among Laya’s possessions, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

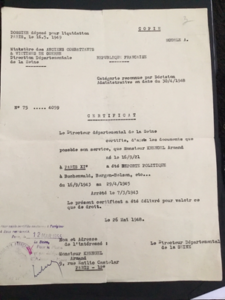

Armand Krengel’s “Political Deportee” certificate, (Family archives, Dominique Krengel)

A message from Dominique Krengel, Henri Krengel’s granddaughter:

Israel, known as Henri, came to France to escape the pogroms* in Poland and the extreme poverty that followed. He arrived in France on October 14, 1919, and married Laya Tellermann, known as Louise.

Louise Krengel, who was born in Warsaw, was 22 years old. She lived with her parents and three brothers, Georges, Gabriel and Adolphe, in the 12th district of Paris, in Faubourg Saint Antoine, where many Jews worked as artisans.

They had also migrated from Poland, at the beginning of the century, following the pogroms and all kinds of abuse*. His brothers all worked in the traditional occupations of Polish Jews: one was a leather worker, one an upholsterer, and the last was a cab driver. That was original!

Laya’s father, my great-grandfather, was an upholsterer who had passed on the trade to his son Gabriel and then to his grandson Armand, my father, who had studied at the Ecole Boulle in Paris.

Armand was Laya’s eldest son, who was deported and returned home in 1945.

The younger brother, Adolphe Tellermann (Henri’s brother-in-law), was deported in 1942, together with his wife Esther, following the Vel’hiv round-up in Paris.

They left behind a little girl of three years old, who was kept hidden during war and then came to live with the family in Faubourg Saint Antoine.

Henri’s wife, Laya, was a seamstress. She was a strong and very intelligent woman.

Having arrived in Paris at the age of 17 with her parents and brothers, just three years later she was speaking accent-free French and also writing it with perfect grammar and spelling.

All these families, Henri’s on one side and Laya’s on the other, wanted only one thing: to integrate.

After their deaths we found some notebooks full of French words to be learned and practiced.

Laya, my grandmother, came from Warsaw with her parents, but they left their grandparents behind, just as Henri left his parents, whom he never saw again.

In Paris, a land of welcome for Polish Jews before the war, Henri’s father-in-law was the owner of an upholstery company that employed staff.

All of them were hard workers.

Grandmother Bella took care of the household and spoke Yiddish for the rest of her life.

Armand, Henri and Laya’s eldest son, joined the Resistance, but was captured in the Pyrenees in 1943, as he crossed the Spanish border.

From there, at the age of 20, he was deported to Bergen Belsen, and then to Buchenwald.

He survived and came back, however.

In 1950, he married Evelyne Wroubel, my mother. They went on to have two children: Dominique and Robert.

Dominique and Robert are what we call 2nd generation survivors, while Garance, Robert’s daughter, is a 3rd generation survivor.

In her book, “Coming Next”, Danièle Laufer, having interviewed various people, describes with great intelligence what life is like for the deportees’ children, grandchildren and close relatives, confronted with the disappearance and (horrific) death of their loved ones.

The generation of deportees in the Polish camps endured unimaginable hardship.

When these deportees came back, they did not speak because people did not want to listen to them.

Many of them have never mourned the loss of their relatives who were burned in the camps.

Laya, Henri’s wife, later worked at the Ministry of Veterans Affairs in Paris.

She died at the age of 86.

Armand, my father, died of leukemia at the age of 44, as a consequence of having been deported, on January 30, 1966, in Paris.

He was awarded the Military Medal and the Legion of Honor as a political deportee.

Henri died on August 5, 1944, in Auschwitz.

Henri was then recognized as having Died for France, and his name is inscribed on the wall of the Shoah Memorial in the 4th district of Paris.

Laya, after some research, obtained a Missing Person’s Certificate for her 16-year-old son Robert, who was never found.

* Note of the authors of the biography: In the books we used to compile this biography, we did not find any evidence of pogroms or anti-Semitic acts in the city at that time. However, anti-Semitism and pogroms did occur in the Czarist Empire and in Prussian controlled areas.

Chapter 6: Work on the project

Participants:

II E: Marta Sadowska, Aleksandra Kurowska

I E : Aleksandra Kubiak, Justyna Mikołajewska, Oliwier Jędrzejczak, Michał Janasik, Oliwia Wiśniewska, Zofia Błaszczyk

I B : Błażej Kraiński, Filip Gachewicz, Martyna Jaroszewska, Martyna Zaroślińska, Anna Wojtczak, Wiktoria Suwała

I D : Maksymilian Michałowski

II B :Nina Bogalecka, Marta Jasińska

Coordinator:

Dariusz Łoboda, French and Spanish teacher.

Visit to the National Archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch. Photo: Dariusz Łoboda

Our team wrapping up the project on 2.06.2012. Photo: Dariusz Łoboda

About the project:

Ania Wojtczak: I learned patience, greater trust and cooperation. (…) We all worked together, and some more did than others, but all of us did something.

Nina Bogalecka: I was surprised how little I knew about my city and the surrounding area before starting the project. I also had the chance to cooperate with some interesting people.

Błażej Kraiński: This was a new experience for me, I always wanted to be part of the “detective business”. I was surprised to discover so many facts about an ordinary man.

Marta Jasińska: I had the opportunity to visit the State Archives, which I think would be impossible in other circumstances.

Martyna Jaroszewska: I was surprised that even an ordinary person, from a small town, harbored so many intriguing stories and secrets. This project was different from other projects

Aleksandra Kubiak: I discovered many interesting websites that helped me find out about what happened to the family.

Aleksandra Kurowska: Each week brought more and more surprising information that pieced our biography together. The project taught me how important it is to keep the story of the dead alive, even in a small way.

Oliwia Wiśniewska: I think this project has made me more aware of human destiny.

Wiktoria Suwała: The project gave us the opportunity to acquire many useful skills.

Zofia Błaszczyk: I didn’t know that by knowing only the first and last name of an unknown person, we could find out so much, or learn how different our lives can be. I also learned so many interesting things about the Jews of Włocławek and Dobrzyń.

Dariusz Łoboda: This is the second time I have participated in this project. I have no doubt of its value. This story is completely different from the last one. Another subject, different participants, a different reality. Last year we were able to visit a number of establishments (Jewish Historical Institute, Polin Museum, Włocławek City Hall) in person. This year the pandemic meant that we worked mainly remotely, although we did manage to visit the State Archives twice.

Working on a historical project requires preparation. There are unexpected discoveries and sudden changes of plan, and extensive research that links together various events, sometimes from very far apart.

At the beginning we only knew the first and last name of a deportee, but in the end, we knew a great deal about his life, we “met” some of his family (about 20 people!) and we found the places they were connected to… Israel Krengel’s story is incredible. We even found the spot where his childhood home was located… Even though he was born 128 years ago and into a poor family!

Dr Adam Sitarek of the Jewish research center at Lódź University:

“A meticulously compiled biography, the level of detail, brilliance, and factual criticism of the sources surpasses that of many students at my faculty.”

Agnieszka Witkowska, author of the Bachelor’s dissertation about the Jews of Dobrzyń:

Congratulations! Very thorough and valuable work! It’s amazing that you managed to find so much information. It makes for very interesting reading!

Dominique Krengel, Israel’s granddaughter:

Bravo Darius for your work and that of your students.

Very interesting and well-documented.

I hope that, together with my contribution, it will enable my grandfather’s soul to be honored, and your students to grasp a part of their country’s history.

Telephone conference call with the support of the project coordinator, Ms Aleksandra Engler Malinowska.

Bibliography:

- Żydzi Włocławscy, Aneta Baranowska, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Grado, Toruń 2008

- Utkane sercem włocławskim Żydom, Mirosława Stojak, Miejsca Biblioteka Publiczna we Włocławku, 2015

- Atlas Historii Żydów Polskich, wydawnictwo Demart, 2010

- Byli z ojczyzny mojej. Zagłada ludności żydowskiej Ziemi Dobrzyńskiej w latach drugiej wojny światowej. Mirosław Krajewski. Wydano z subwencji Benjamina Stencla z Ramat-Gan w Izraelu. Rypin 1990.

- Tomasz Kawski. Ludność żydowska na Kujawach wschodnich i w ziemi dobrzyńskiej w okresie międzywojennym.

- Agnieszka Witkowska – praca licencjacka poświęcona Żydom Dobrzyńskim.

- Album Ziemi Dobrzyńskiej; Lubomir Dmochowski; Lipno 1908

- Gminy żydowskie pogranicza Wielkopolski, Mazowsza i Pomorza w latach 1918-1942; Tomasz Kawski; Toruń 2012.

- Patrick Modiano „Dora Bruder”

Sites Internet/Sources:

https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/d/1035-dobrzyn-nad-wisla

http://zydzi.wloclawek.pl/

https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en&

www.jri-poland.org

http://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/resultat.php?type_rech=rs&index%5B%5D=fulltext&bool%5B%5D=&value%5B%5D=krengel&spec_expand=1

https://arolsen-archives.org/ueber-uns/standpunkte/online-archiv/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI5-uz3P7T7wIVqhJ7Ch2zaQITEAAYASAAEgLL1fD_BwE

www.memoiredeshommes.sga.defense.gouv.fr

https://www.ushmm.org/online/hsv/person_view.php?PersonId=4307412

Cmentarz żydowski w Dobrzyniu nad Wisłą Jewish cemetery in Dobrzyn (cmentarze-zydowskie.pl)

krengel – Recherche (rhone.fr)

http://forum.tradytor.pl/viewtopic.php?t=5009%20http://cmentarze-zydowskie.pl/dobrzyn.htm

http://www.listyznaszegosadu.pl/pl/article_print.php?id=602783

https://www.myheritage.pl/research/collection-1/drzewa-genealogiczne-myheritage?s=1&formId=master&formMode=1&useTranslation=1&exactSearch=&action=query&p=1&qname=Name+fn.Israel+fnmo.1+ln.Krengel+lnmo.3&qevents-event1=Event+et.birth+ey.1893&qevents=List

https://www.jewishgen.org/jgff/jgffweb.asp.

http://genealogyindexer.org/

KRENGEL – GénéaFrance (geneafrance.com)

[1] Thèse de licence d’Agnieszka Witkowska: ZARYS DZIEJÓW GMINY ŻYDOWSKIEJ W DOBRZYNIU NAD WISŁĄ W ŚWIETLE ZACHOWANYCH ŹRÓDEŁ (1507-1939); APERÇU DE L’HISTOIRE DE LA COMMUNE JUIVE DE DOBRZYN SUR LA VISTULE À PARTIR DES SOURCES (1507-1939)

Coopération (par ordre d’apparition)

- Serge Jacubert – Project Coordinator, France

- Aleksandra Engler-Malinowska – Project Coordinator, Pologne

- Georges Mayer – Project Coordinator, Israël

- Claire Podetti – Project Coordinator, France

- Anna Przybyszewska Drozd – Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw

- Rafał Więckowski – State archives of Toruń, Włocławek branch

- Dr Adam Sitarek – Center for Jewish Research, University of Łódź.

- Mirosława Stojak – Expet on the subject of the Jews of Włocławek.

- Paweł Śliwiński – Historian of Dobrzyń nad Wisłą

- Krzysztof Bielawski – Historical Information Center of the POLIN Museum

- Ryszard Bartoszewski – Dobrzyń town hall

- Krystyna Andrzejewska – proofreading, translation from Russian

- Wiesława Podgórska – photos.

- Grażyna Witkowska – consultation, project materials.

- Agnieszka Witkowska – author of a Bachelor’s dissertation on the Jews of Dobrzyń.

- Dominique Krengel – Israel’s granddaughter.

On behalf of my students, the participants in the project, I would like to thank all the people, organizations and parties involved for their invaluable help, time, goodwill and productive cooperation. I would like to thank the project organizers for giving us the opportunity to take part in such a valuable project.

Dariusz Łoboda

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Merci beaucoup Monsieur Loboda , pour le superbe travail , que je vous avez fait avec vos élèves .Au delà de toute attente,vous avez réanimé l’âme de mon grand père .

Hier soir pour mon anniversaire,j’ai invité ma nièce et son ami au restaurant ,et je leur montré votre travail.Ils étaient tous intéressés et émus .

Replacer les membres de notre famille dans l’arbre généalogique , fait aussi partie ,pour ceux qui le veulent ou le peuvent de notre verticalité retrouvé.Car ce génocide a aussi créé de graves coupures dans notre univers familial de survivants ,deuxième et troisième génération comprises.

Lorsque je viendrai en Pologne( j’espère avec ma nièce , Garance Krengel,puisque je n’ai pas d’enfant) , nous ne manquerons pas de venir vous saluer.

Mais un petit point me travaille encore :

– Êtes vous sûr qu’il n’y avait pas de pogroms à cette époque ?

Ce n’est pas ce que dit le livre des pogroms ,et d’autres documents.

Pourriez vous nous éclairer sur ce point?

Si c’est possible pour vous bien sûr , et ne crée pas d’enjeux difficiles.

Encore MERCI Monsieur Loboda .

Merci aussi à Monsieur Meyer ,sans qui rien ne serait possible ,et Madame Podetti du lycée de Palaiseau ,avec laquelle nous avons passé de longues soirées à reprendre et mettre à jour des informations.

Bonjour de Pologne,

Je suis très heureux que vous ayez apprécié le travail de mes élèves. Je suis également heureux que vous l’ayez présenté à votre nièce et à son ami. Je suis sûr qu’ils pourraient être émus. Cela fait partie de leur histoire.

Si vous venez en Pologne, nous serons heureux de vous rencontrer, de faire votre connaissance en personne et de vous montrer la ville natale de votre grand-père.

Quant aux pogroms, comme nous l’avons écrit dans la biographie, dans les livres qui nous avaient servi pour préparer la biographie, nous n`avons pas trouvé de preuves confirmant les pogroms ou actes antisémites répertoriés à cette date dans la ville. Néanmoins l’antisémitisme et les pogroms avaient eu lieu dans l’Empire tsariste et sur le territoire occupé par la Prusse.

Nous nous sommes également adressés à un historien universitaire qui a les outils scientifiques appropriés. Il n’a pas non plus trouvé cette information.

Merci encore pour votre contribution. Nous sommes ouverts et nous restons à votre disposition.

Veuillez agréer, Madame, l`expession de nos sentiments distingués.

Dariusz Łoboda

This is a great piece of research on a very sorrowful subject.

I actually came across it as I was studying my family tree and found a Krengel DNA match in Paris. From there, I discovered the history of Convoy 77.