Léon MEYER (1877-1944)

Who are we?

We are a group of students in class 4B AFM at the De Viti de Marco high school in Triggiano in Bari, in the Apulia region of southern Italy. With the guidance of Ms. Paola Barone, our French as a foreign language teacher, we first found out about the Convoy 77 project in February 2021. We found the project an interesting proposition: to tell the story of Léon Meyer, a French Jewish citizen who was deported to Auschwitz on the last transport from Paris in July 1944.

For this project, we took on the role of investigators. With the help of Mr. Serge Jacubert and the Convoy 77 project team, we gained access to a wealth of archive material which enabled us to put together this biography. But we still needed more… We therefore searched for photos of Léon but were unable to find any. We also approached Ms. Filomena Montella, a history teacher at our school, who helped us to better understand the historical events that are usually only covered in the final year in high school (in our case, 5th class), including the Nazi occupation, what happened to the Jews in France, the Vichy regime and the Liberation.

This has been a very moving experience for us, which culminated in an online presentation of the project in Jerusalem on April 28, 2022, on the occasion of “Yom HaShoah“.

Why this project?

To understand this, we must read Primo Levi’s poem:

Se questo è un uomo

Voi che vivete sicuri

nelle vostre tiepide case,

voi che trovate tornando a sera

il cibo caldo e visi amici:

Considerate se questo è un uomo

che lavora nel fango

che non conosce pace

che lotta per mezzo pane

che muore per un sì o per un no.

Considerate se questa è una donna,

senza capelli e senza nome

senza più forza di ricordare

vuoti gli occhi e freddo il grembo

come una rana d’inverno.

Meditate che questo è stato:

vi comando queste parole.

Scolpitele nel vostro cuore

stando in casa andando per via,

coricandovi, alzandovi.

Ripetetele ai vostri figli.

O vi si sfaccia la casa,

la malattia vi impedisca,

i vostri nati torcano il viso da voi.

Primo Levi

If this is a man

You who live in peace

In the warmth of your homes,

You who come home in the evening

To hot food, and friendly faces,

Consider if this is a man,

Who toils in the mud

Who knows not rest

Who fights for a crust of bread

Who dies because someone says yes or no.

Consider if this is a woman,

With no hair and with no name

Without even the strength to remember

Her eyes vacant and her womb cold

Like a frog in winter:

Never forget that this happened:

No, never forget:

Inscribe these words on your heart

Think of them at home and when you go out,

When you go to bed and as you get up;

Repeat them to your children:

Or may your house be destroyed,

Or sickness befall you,

Or your children turn away from you.

The Second World War was a time of unprecedented violence and crimes against humanity. While the survivors were able to bear witness to the horror of the camps, and describe how the victims suffered and were dehumanized, the dead remained silent forever. The Nazis’ mass murder stripped them of their humanity and dignity. Turned to ashes, with no graves for loved ones to mourn them and no inscriptions to commemorate them, they fell into anonymity.

The Convoy 77 project is all about chronicling the life of each and every victim aboard this death train: who they were, how they lived and why they died. The last convoy to leave Drancy on July 31, 1944, this was the starting point for uncovering, retracing and recounting Léon Meyer’s life story.

Why Léon?

Because he was born in south-east France, not far from the Italian border.

Léon Édouard Meyer 1877-1944

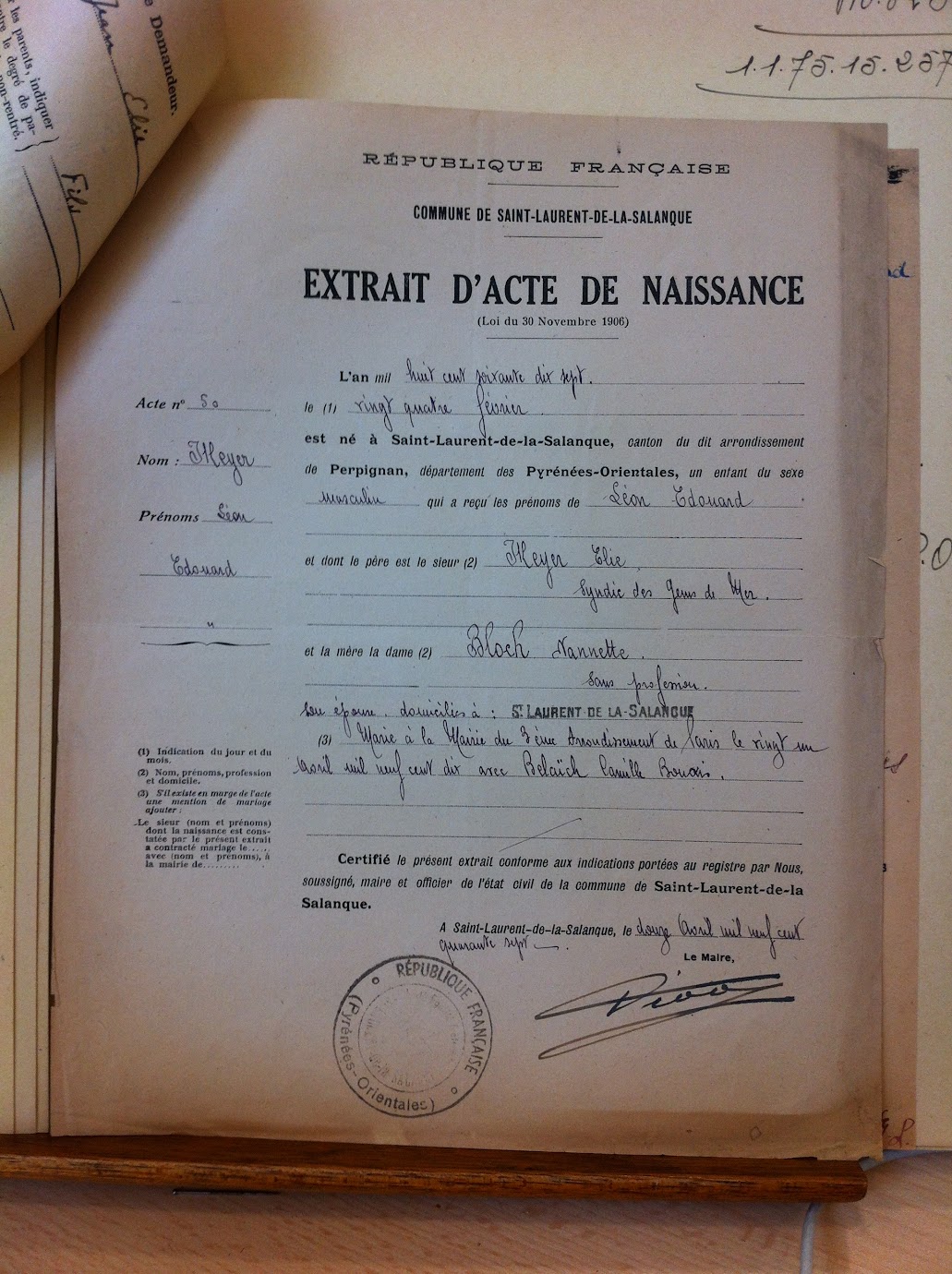

Léon Édouard Meyer was born on February 24, 1877 in Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque, in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France.

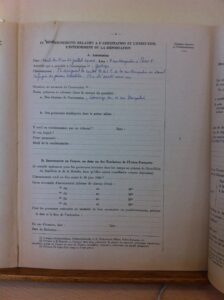

Léon Meyer’s birth certificate. Sadly, there are no photographs of him.

Source: Saint-Laurent-de-La-Salanque town hall

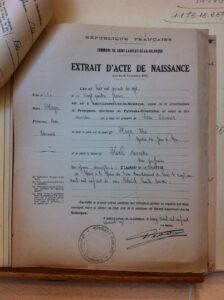

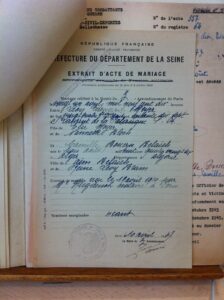

Léon was married to Camille Boucris Belaïch, who was born on August 3, 1890.

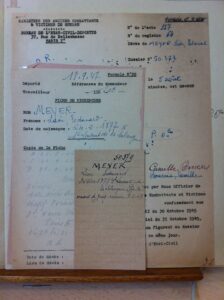

Marriage certificate, from the Prefecture of the Seine department of France.

They had two children: Jean Elie, born on April 30, 1912 and Suzanne Reine, born on May 28, 1914.

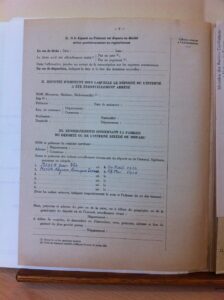

Information about Léon’s family.

Source: Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, Paris.

He was arrested during the night of July 21-22, 1944, when the Gestapo raided the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews) home on rue Vauquelin in Paris, of which he was the manager.

The concierge at 11 rue Vauquelin witnessed the arrest.

Source: Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, Paris.

Among the earliest of the Vichy regime’s anti-Semitic policies was the law of October 4, 1940, which introduced internment of foreign Jews resident in France. The Germans’ mass arrests of Jews, first in the occupied zone and subsequently in the free zone marked the second stage, when French Jews were interned as well. Drancy camp then became the antechamber to Auschwitz, where the “Final Solution” was put into effect.

On July 21, 1944, Léon was arrested. On the 22nd, he was interned in Drancy. From there, he was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944.

Source: Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, Paris.

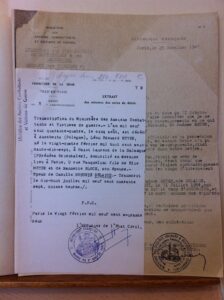

His official date of death is August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Léon Edouard Meyer’s death certificate was issued in Paris on July 18, 1947.

Minutes of the decision of the date of death.

Prefecture of the Seine department, 5th district of Paris

Death certificate.

Minister of the Civil Registry of Deportees from Paris

His last address was 9, rue Vauquelin, Paris. Rue Vauquelin was a street in the Val de Grace neighborhood of the 5th district of Paris.

Rue Vauquelin, 5th district of Paris

Source: Wikipedia

The raid on the rue Vauquelin children’s home

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, the Germans raided 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris, which was the former headquarters of the Séminaire Israélite de France (Jewish Seminary of France), which, like other Jewish organizations, had been banned from operating during the war. At the time, it was being used as a UGIF home for girls, and 33 Jewish girls were staying there. Many of them were deported from Drancy on Convoy 77, on July 31, 1944, the last major convoy to leave Bobigny station, heading for Auschwitz.

Among the adults deported from Drancy on Convoy 77 were:

- Camille Meyer (née Belaich) (58 years old)

She was born on August 3, 1886 in Algiers, Algeria. Her husband, Léon Meyer, was also deported on Convoy 77.

- Léon Meyer (67 years old)

He was born on February 24, 1877 in Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque. This is our Léon!

Convoy 77

Convoy 77 was the last major transport of Jews from the Drancy internment camp in Paris. It left Bobigny railway station on July 31, 1944, bound for the Nazi extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

There were 1,309 people on board, including 324 children and babies, all crammed into cattle cars.

It arrived during the night of August 3, and the “selection” process began immediately. The official date of death for all of the deportees who were not selected to work in the concentration camp was later determined to be August 5, 1944.

At the end of the war, on May 9, 1945, only 251 of the people deported on Convoy 77 were still alive; 847 were exterminated in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived.

Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of the Drancy camp, who was already under pressure from the advancing Allied troops who had landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944, was spurred on by the confusion caused by the failed attempt on Hitler’s life on July 20. He took advantage of the situation to press ahead with his killing spree. He was determined not to leave any Jewish children behind, and rounded them up in places where he was sure to find them. These included the UGIF children’s homes in and around Paris, and other homes in which they had been placed.

More than 300 children (including 18 babies and 217 children aged 1 to 14) were arrested, taken to Drancy and deported on Convoy 77. Among them were 20 little girls from an orphanage in Saint-Mandé, together with the manager, Thérèse Cahen, who went with them to the gas chambers.

The people on the convoy

Léon traveled for three days in a cattle car, on his feet, with no food or water. When he arrived at Auschwitz, men in gray and blue striped suits told him to get out and to split up with the others: men to the left, women to the right!

The majority of deportees (55%) were born in France: There were also people of 35 different nationalities, including, other than French citizens (which included Algerians), Poles, Turks, Russians (in particular Ukrainians) and Germans.

There was a significant number of children (324) on this convoy, and 125 of them were under 10 years of age.

Drancy: Léon was arrested on July 21, 1944 and arrived at Drancy on July 22, 1944

Drancy camp in August 1941.

Source: Wikipedia

From August 1941 through August 1944, Drancy internment camp was the hub of the anti-Semitic deportation policy in France. Located northeast of Paris, in the town of Drancy (which at that time was in the Seine department, but is now in Seine-Saint-Denis), the camp was the main internment site for Jews prior to their deportation from the Bourget railway station (1942-1943) and then the Bobigny railway station (1943-1944) to the Nazi extermination camps, mainly Auschwitz. Nine out of ten Jews deported from France passed through the Drancy camp during the Holocaust.

A cattle car at the Drancy Memorial.

Source: Wikipedia

The Drancy internment camp was set up in October 1939, in a vast U-shaped complex that was part of a low-cost housing estate known as the “Cité de la Muette“, designed by architects Marcel Lods and Eugène Beaudouin. Built between 1931 and 1934, it also included five fifteen-story high-rise blocks, as well as several three and four-story buildings arranged in the shape of a “comb”.

A deportation center

A round-up of Jews in Paris, August 20, 1941.

Source: Wikipedia

The camp was first and foremost an internment center, where living conditions were intentionally tough: malnutrition soon resulted in dysentery, and some of the French military police officers abused the internees, inflicting arbitrary punishments and humiliating them.

As of 1942, when Nazi Germany turned to the Final Solution, Drancy was no longer an internment camp, but a transit camp, and the last stop before the Jews were deported to the extermination camps.

Jews arriving in Drancy, August 1941.

Source: Wikipedia

Jewish internees in Drancy camp.

Source: Wikipedia

Up until July 1943, German soldiers and French military policemen travelled on the transports. Later on, police officers were sent from Germany to escort the convoys.

Léon’s arrival in Birkenau Auschwitz

Léon arrived in Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 and five days later, at the most, he was dead.

Auschwitz was the largest of the Third Reich’s concentration camps and extermination centers. Formerly an army base, it was in the province of Silesia, some 30 miles west of Krakow, in the vicinity of Oswiecim (Auschwitz in German) and Brzezinka (Birkenau in German), which had been annexed to the Reich after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939.

The concentration camp, run by the SS, was set up on April 27, 1940 on Heinrich Himmler’s orders; it was extended to include an extermination center (the construction of which began at the end of 1941) and a second concentration camp for forced labor (set up in the spring of 1942). The Red Army liberated both camps on January 27, 1945. The entire camp and various adjoining sites, including an area with a stretch of railroad line, covers an area of around 21 square miles. The camp alone covered an area of almost 4 square miles. The site, now in Poland, is now a permanent memorial.

Witnesses from Convoy 77

Yvette Lévy, a survivor from Convoy 77, who was deported at the age of 18.

Source: Wikipedia

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, the Gestapo arrested Yvette Lévy, a young Jewish woman who had just turned 18, and took her away, together with the other children from the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin in Paris.

“In the middle of the night, we were woken up, shaken and arrested. I still have his eyes in my head, of the German who was standing there yelling “Get up and hurry! Move faster!”.”

She was plunged “into hell”: a hell she has been committed to sharing for many years, testifying in various schools (taken from Marjorie Lenhardt’s article on leparisien.fr, July 21, 2019 at 7:24 pm). When she arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1944, Yvette Lévy was kept in quarantine for three months. Of the people on her convoy, 900 were sent straight to the gas chambers and killed (including our Léon), while 200 were sent to labor camps. Yvette Lévy was subsequently sent “deep into the Sudetenland”, to the Kratzau labor camp in Czechoslovakia, where she worked 12 hours a day in a weapons factory. She stayed there until the Liberation.

Of the 1,309 deportees who arrived at Auschwitz on Convoy 77, more than half, including all the children, were immediately sent to their deaths in the gas chambers. 291 men and 183 women were selected for forced labor.

When the war ended on May 9, 1945, only 251 deportees had survived the forced labor, abuse, Nazi pseudo-medical experiments and deprivation: 93 men and 158 women. The full list of people deported on this transport is available here on the Convoy 77 non-profit organization website, along with over a hundred biographies.

Conclusion

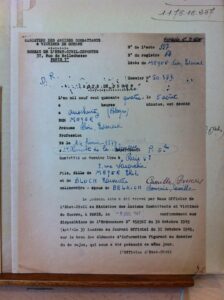

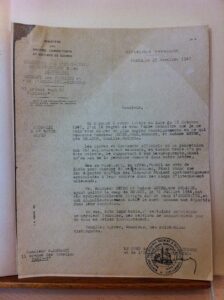

Letter dated November 25, 1947.

Source: Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War.

Paola:

“A moving, rewarding and even painful experience! After reading this letter (dated November 25, 1947, from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War), I couldn’t hold back my tears. The sentence: “…deportees from the era of the “disappeared” were systematically EXTERMINATED on arrival in the German internment camps were systematically EXTERMINATED on arrival in the German internment camps” seems so very harsh!”

Français

Français Polski

Polski