Suzanne SOUSSI

Suzanne Soussi, a courageous young woman

Suzanne Soussi, who was born in Paris in 1927, was arrested in 1944. Initially interned in Drancy camp, she was deported to Auschwitz and then transferred to Kratzau. She was liberated by the Red Army in 1945, after which she returned to France.

CHILDHOOD

Suzanne Soussi was born on May 26, 1927, in the maternity ward of the Rothschild hospital in the 12th district of Paris. Her parents were Avram (known as Albert) Soussi, born on March 25, 1905 in Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire, and Perla Horada, a homemaker born on April 8, 1905, also in Constantinople. Albert had a younger brother, Alfred, who was born on October 25, 1913, in Constantinople, and later lived in Marseille on the south coast of France. Albert/Avram’s parents, Yomtov and Sultana, died sometime prior to 1926.

Perla’s parents, Avram, born on April 9, 1872 in Constantinople and died on January 16, 1927 at the Goussainville train station, and Vida, known as Victoria (Bia?) Horada, who died in Paris in 1943, moved to France sometime between 1918 and 1924. Like many others, they fled the War of Independence in Turkey after the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Did Perla and Avram first meet in Turkey? Might they have been “promised” to each other by their families? Either way, they got married in Paris, at the town hall of the 11th district, on August 14, 1926. At the time, he was living at 12 cité Lemières, and she with her parents at 3 impasse

Source : City of Paris online archives. 11th district of Paris. Marriage register.

When Suzanne was born, the couple were living at 22 rue Kléber in Montreuil, east of Paris. Suzanne grew up in France and became a French citizen by naturalization in 1929 (as she stated on the medical form when she returned from the camps). Her father worked as a cobbler. Her mother had trained as a furrier, but does not appear to have gone out to work, instead devoting her time to her home and her children’s education.

Suzanne with her parents, Albert Soussi and Perla Horada, in 1929

On March 23, 1930, the family expanded with the birth of Suzanne’s little brother, Freed (sic), who was also born in the 12th district of Paris.

As a girl, Suzanne trained as a seamstress, and in 1936, according to the census, she was living with her parents and brother at 3, impasse Popincourt, in the Roquette district of the 11th arrondissement of Paris. The two nearest elementary schools were the Parmentier and Godefroy-Cavaignac schools. We were unable to determine with any certainty, however, which of them Suzanne or her younger brother went to.

In 1938, Haïm Vitali Horada, who was born on October 10, 1914 in “Stamboul” and died in 2014 in Villers-lès-Nancy, was living at the same address. He was a fairground merchant, according to his voter registration card for the Roquette 1 ward. He was already living in this building in 1931, with his mother Victoria, born in 1881 in Turkey, and Hersa (Sarah), also born in 1913 in Turkey (1931 census, Roquette, p. 203). At the time, he was a mirror-maker. He was Perla’s younger brother. At that time, however, Suzanne’s family had not yet moved into the building.

This neighborhood, and more specifically this dead-end street, was home to many Jewish families originally from Turkey.

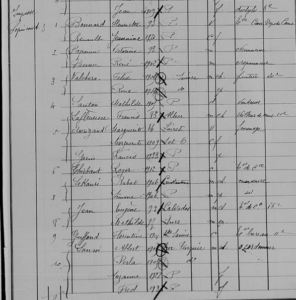

The Soussi family at the time of the 1936 census

Sources : État-civil de la Ville de Paris en ligne

Source: The online City of Paris civil register

PERSECUTION AND WARTIME

The arrest of her parents

The Soussi family had to endure all the hardships caused by the anti-Semitic policies of the German occupying forces and the French state. Albert may well have lost his job as a result. However, they stayed on in the same neighborhood.

Albert was arrested and deported in 1942. We found two contradictory pieces of information about this. According to the Shoah Memorial website, he was deported on Convoy No. 3 on June 22, 1942. The 1000 people on that convoy were all selected for forced labor, but according to Serge Klarsfeld, only 34 survived until 1945 and Albert was not among them: he died on July 28, 1942 in Auschwitz.

Extract from the deportation list of the convoy on which Albert Soussi was deported

Source: The Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation

According to a record on the Yad Vashem website, Albert Soussi was deported in September 1942. The first piece of information would seem to be correct, however.

Source: Yad Vashem website

After her father was arrested, Suzanne continued to live with her mother, Perla, and her brother until Perla was arrested in March 1944. She was taken to Drancy camp on March 27 and deported on April 13 on Convoy no. 71. She never returned to France. On the Drancy camp search card, it is noted that she had to hand over the sum of 150 francs that she had on her when she arrived. This suggests that Suzanne, Freed and their mother were struggling to survive. Among the various anti-Semitic policies, exclusion from work and business activities hit Jewish families hard.

Was Suzanne arrested at the same time as her mother? In a handwritten statement dated December 11, 1955 (file ref. 21 P 609 379 from the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy), her brother, Freed, states that his sister was arrested on “?” May 1944. If this record is to be trusted, it would mean that Suzanne was arrested after her mother, and placed in the care of the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews). Or perhaps Freed viewed the fact that Suzanne was entrusted to the UGIF, which was entirely under the control of the German authorities, to be equivalent to an arrest? We note, however, that on the medical form she completed when she returned to France, Suzanne gave her last address in France as 50 rue de Sedaine, and this was where she wanted to go back to. It was most likely that of her maternal aunt, Sarah Horada, Ahmed Dahmani’s wife (source: Généanet). Might she have gone into hiding there before her aunt placed her in the care of the UGIF?

The roundup at the children’s home on rue Vauquelin

Whatever happened, when Suzanne was finally arrested, she was living in a home for young Jewish girls at 9 rue Vauquelin, which the UGIF had founded in January 1943. Most of the girls there were orphans, but some had been placed there by their families, thinking that it was a safe place to hide them.

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, tragedy struck the quiet home at no. 9 rue Vauquelin. At the time, it was home to some thirty Jewish girls, including Suzanne Soussi. Some went to high school, while others were serving apprenticeships or working. According to Suzanne’s testimony, they were all woken up at 5 a.m. and arrested, still in their nightgowns, as were the Jewish staff. They were told they were going for an identity check. But this was merely a pretext. According to Yvette Levy, another survivor, it was Aloïs Bruner himself, the commandant of Drancy camp, who led the arrest and loaded them into a tarpaulin-covered truck bound for Drancy camp. Almost all were deported, never to return. The arrests took place as part of a series of roundups of all the UGIF homes in and around Paris.

Suzanne was assigned a serial number, 25497, and then she and her friends were placed in filthy, vermin-ridden dormitories. She did not stay long in the Drancy camp, however. On 31st July, 1944, she was deported on the last of the large convoys from the Paris area: Convoy 77. On August 17, Brunner and the Nazis fled the camp for Buchenwald, taking some hostages with them. The remaining prisoners found themselves free to go, and soon left the camp. But for the prisoners deported on Convoy 77, the horror had only just begun.

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 609 379

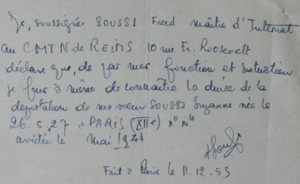

We know that her brother, Freed, was not deported, because in 1953, at which time he was a boarding school teacher in Reims, he wrote the above letter about his sister, which is included in her deportation file.

Was he one of the thousands of Jewish children who were kept hidden in France and Switzerland? This is what the testimony of his “cousin”, published on the CRIF Facebook page in March 2017 suggests, as part of a tribute to Odette Rosenstock, who founded the Marcel (Moussa Abadi) network that hid over 500 children. Freed is said to have been hidden, via this network, in an abbey in the Eure department of France. He died on December 16, 1996, in the 18th district of Paris.

Deportation to Auschwitz and then to Kratzau

Suzanne was deported from Bobigny station to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. The journey took three days and three nights. There were 1306 people on board, including a week-old baby, a number of elderly people and three hundred children, all crammed into cattle cars in the midst of a heat wave. There were sixty to a hundred people in each car, with no sanitary facilities and hardly and drinking water.

When the convoy arrived, and the children, seniors, women with children and most of the other prisoners were taken to the gas chambers and killed, Suzanne was deemed fit enough to be selected to work. She was taken into the Birkenau-Auschwitz camp. Another deportee tattooed the number 16807 on her left forearm. It was still visible on August 24, 1955, when she showed it to the person responsible for verifying her story.

“We went to the disinfection room. They beat us to make us get undressed. We didn’t want to stand naked in front of these men. Then we lined up to be shaved and shorn. The shame of it… We were traumatized,” recounts Yvette Lévy, née Dreyfus, also from rue Vauquelin, who followed the same route as Suzanne and was transferred to Czechoslovakia at the end of October.

On September 24, 1944, Suzanne was transferred to the camp at Kratzau (Weisskirchen).

Kratzau was close to the town of Chrastava in northern Bohemia, in Czechoslovakia. Since the Munich Agreement of 1938, this Sudetenland town had been annexed by the Third Reich, and during the Second World War, a concentration camp for women was built nearby. This is where Suzanne worked, in the Spreewerk factory, making ammunition for the German army. Kratzau was one of several subcamps of the larger Gross-Rosen camp.

Gross-Rosen and its sub-camps

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Below is an overview of a typical day at the camp:

- 3:30 a.m.: Wake-up call. Beds had to be made.

- 4.15 a.m.: Roll call in the dormitories.

- 4.20 a.m.: The girls took turns to “exodus” into the courtyard to fetch breakfast. Breakfast was a watery soup made from potatoes or vegetables, thickened with raw potato peelings. Female prisoners were given about 1 ½ pints of water per person. At the same time, they got their daily ration of bread, about half a pound, with a tiny bit of margarine, a slice of sausage or a little spoonful of jam.

- 5.05 a.m.: Roll call in the courtyard for the girls going to the factory.

- 5.20 a.m.: Set off for the factory on foot.

- 6.00 a.m.: Arrive at the factory and start the working day.

- 9.00-9.15 a.m.: Morning break.

- 11.30 a.m. -12.00 noon: Lunch break. Lunch was of half a cup of hot liquid, ersatz coffee or mint tea drunk with the rest of the bread ration.

12 noon-6pm: Work in the various workshops. - 6.10pm: Roll call in the factory courtyard and return to camp.

- 7:00 pm: Arrival at the camp and second roll call in the courtyard, then waiting for soup to be handed out.

The evening soup, of which the girls had about two pints, was also made from potatoes, but it was thicker and usually included some whole potatoes in their skins, mixed with a few beet. “Once a week, we got the usual potatoes with a little meat sauce and, occasionally, onions. On Sundays, too, we were allowed potatoes with a little meat sauce. A further detail about the food: “There was no salt for the last fortnight in the camp”, one prisoner recalled.

- 9 p.m.: Curfew.

This work schedule, coupled with very limited food intake, inevitably resulted in the women suffering from exhaustion. “We did have an advantage over our girlfriends in terms of working conditions though,” Yvette Lévy insisted in 2019.

Suzanne and her friends were liberated by the Russian army on May 9, 1945.

“On May 7, there was no work, but the order was given to assemble all the girls (both day and night shifts), prompting questions and alarm among the deportees. The factory manager, who arrived in a chauffeur-driven car, announced that the end of the war was near, and wished them all the best of luck in returning to their respective countries! The woman in charge, who was officially the “commandante”, but nick-named Napoléon, because she always had one hand in her blouse and the other behind her back, was furious. During the night of May 8-9, 1945, the SS had vanished, leaving only their uniforms behind, but they mined the camp. First some Czech partisans and then the Russians moved into the camp: this was “liberation”, recounts Yvette Lévy (see Yvette Lévy’s biography on this site). Did Suzanne, like Yvette and one of her friends, roam around the nearby farms in search of a few eggs to gobble up? We found no trace of her testimony, if indeed she ever made one.

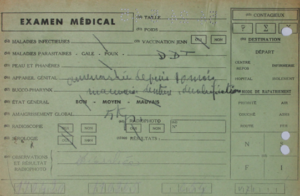

There is only the medical form, which was filled in when she returned to France, to describe Suzanne’s physical condition. It mentions “numerous physical problems caused by the deportation: amenorrhea (absence of menstruation), loss of calcium, bad teeth”. She was treated with DDT, to kill lice and other parasites. She had lost 11 pounds since she was deported, and her overall condition was considered to be “average”.

Suzanne Soussi’s medical exam card, completed when she returned to France

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. ref. 21 P 609 379

Suzanne was repatriated on May 24, 1945, fairly soon after she was liberated from Kratzau. She went to the Hotel Lutetia, the main repatriation center in Paris. On her card, she wrote that she wanted to go stay with Mrs. Dahmani at 50, rue de Sedaine, who was most likely a relative (see above). The apartment was just 250 yards or so from impasse Popincourt, where the Soussi family used to live. She did not yet know that her parents were dead, but she must have suspected as much, having been an eyewitness to the genocide.

AFTER THE WAR

Suzanne Soussi married Georges Robert Friedmann (1922-2022) on April 29, 1954, at the town hall of the 5th district of Paris. She was living in this district, at 6 rue Lagarde, when she applied for the status of “political deportee” (meaning that she was deported for political reasons, on grounds of her “race”). For some time after that, she lived with her brother at 30 rue Vieille du Temple, in the Marais district, then at 19 rue Descombes in the 17th district, as evidenced by correspondence with the authorities and her deported person’s file. However, her file shows that she then moved to Toulon, in the south of France, which is where she had her deportation card stolen by a pickpocket. It would appear that she lived there for the rest of her life.

After extensive research, we found no trace of any descendants. We began by searching the online birth registers. However, birth certificates for the years in which Suzanne might have had a child are only available on request and for personal or family reasons, which does not apply to us. We therefore searched for family members in order to contact them to ask if Suzanne had had any children. Unfortunately, we were unable to contact the cousin we traced. Another cousin, on her mother’s side of the family, knows very little, as she is thirty years younger! However, when we researched Suzanne’s death, we noticed that no children were mentioned in the death notice, although some other family members were. We therefore conclude that she never had any children of her own.

In her application for political deportee status, she stated that she worked in the leather goods trade.

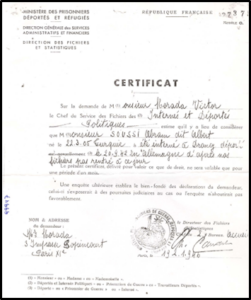

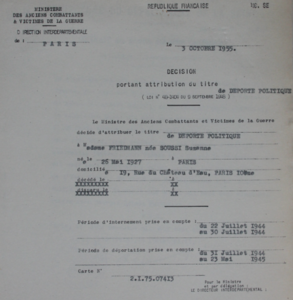

Notification of the granting of political deportee status (1955)

Suzanne Soussi was granted political deportee status in 1955.

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. ref. 21 P 609 379

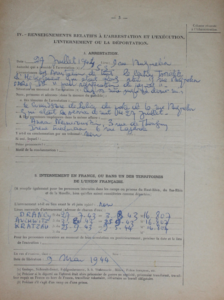

A closer look at her application raised a few questions. In fact, the dates she mentions do not tally with what happened to her. For example, she stated that she was arrested in 1943 and liberated in 1944. Even the date on which she arrived in Drancy is wrong (it was July 22, rather than July 27). It’s almost as if she wanted to erase these traumatic events from her memory, by wiping out an entire year… The person who dealt with the file didn’t even correct it, aside from the departure date of the convoy!

Extract from Suzanne Soussi’s application form for political deportee status (1954)

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. ref. 21 P 609 379

In conclusion, the life of Suzanne Soussi, who was deported during the Second World War on Convoy 77, is a poignant testimony to her resilience in the face of the horrors of deportation. Sadly, her story came to an end on November 18, 1999, in Toulon. Her courage and struggle to survive continue to serve as an inspiring reminder of the harsh reality and the terrible cruelty of that period in history.

Suzanne Soussi will always be part of our collective memory, reminding us of the importance of remembering and passing on the lessons of the past.

Sources

- French Defense Historical Service

Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division, ref. 21 P 609 379

- The Shoah Memorial in Paris

The Drancy files, search log and transfer book

- Vielle de Paris municipal archives online

The 1931 and 1936 censuses of Paris.

Français

Français Polski

Polski