Louise PISANTI

We are Sofia, Emma, Elisa, Anaïs, Aaron and Pierre-Alain. We are in 9th grade at Les Blés d’Or secondary school. This biography was written as part of the Convoy 77 project. We are going to tell the story of Louise Pisanti, a Jewish girl who was deported on Convoy 77. We were able to write it with the help of the archived records provide to us by the Convoy 77 nonprofit organization, our own research on the internet, survivors’ testimonies and personal experience (such as our trip to Berlin and our visit to the Drancy internment camp).

We chose to focus on Louise Pisanti because she was a teenager who was deported at the age of 14, the same age that we are now. There was also much more archived material available about her than about the rest of her family, which we felt would enable us to produce the most comprehensive biography possible. With the support of our French and History/Geography teachers, we decided to write her story in the first person.

BIOGRAPHY

My name is Louise Pisanti and I was born on July 28, 1930 in the Rothschild Jewish Hospital in the 12th district of Paris.

The Rothschild Jewish Hospital, in the 12th district of Paris

Louise Pisanti’s birth certificate

On Louise’s birth certificate, we can see her name, her parents’ names, and that she was born on July 28, 1930. However, it does not mention exactly where she was born, just that it was in the 12th district of Paris. We assume therefore that she was born in the Jewish hospital in the 12th district, the Rothschild Hospital at 5 rue de Santerre, not far from where the family lived.

Photos of Louise Pisanti (on the left) and of the Pisanti family (on the right)

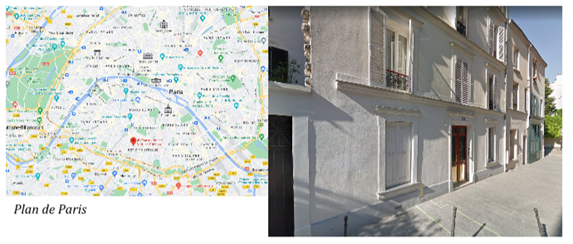

Ever since I was born in 1930, I had lived at 49 rue du Moulin Vert, in the 14th district of Paris.

49 rue du Moulin Vert

49 rue du Moulin Vert

I lived in an apartment with my father and mother and my two sisters, both of whom were older than me. One was called Bequi, she was born in 1925, and the other was Victoria, who was born in 1927. All three of us were French citizens because we were born in France. My father, who was called Albert Pisanti, was an electrician. He was born on April 24, 1899 in Constantinople in Turkey, as was my mother, Fortunée Pisanti, née Tchiparel, who was born on February 20, 1901 and was a seamstress. They were Jewish Turks and were stateless persons. A stateless person is a person that no state recognizes as one of its citizens. This means that the stateless person falls under the legal jurisdiction of a country other than the one in which he or she is resident. My parents had to leave Turkey because the Turkish government no longer wanted Jews in the country after they renounced their rights under the Treaty of Lausanne. After that, my father was fired from his job and he then moved to France in search of a better life.

My family and I were Jewish but we were not very religious. We only went to synagogue on special holy days. I was never really involved in my religion and did not pray very often. I went to school as soon as I was old enough, which was around 1934. I went to the Alesia public elementary school which was about ten minutes from our apartment.

The route from rue du Moulin Vert to the Alésia elementary school

Rue d’Alésia

I didn’t learn about religion at school either. My childhood was quite happy and I did not want for anything. My family was not rich, but we were comfortable. I had some good friends at school and I got along well with the other children. I was happy to go to school because I liked meeting my friends and enjoyed learning new things.

My mother and my aunt both had apartments in Villepinte, in the northern suburbs of Paris, about twenty miles from the city center.

In 1939, we heard the news that war had been declared. I was worried about what might happen to us, but at nine years old, I didn’t understand what being at war really meant.

It was in June 1940, after France was defeated, that my sisters and I had to begin hiding from the Germans due to the persecution of the Jews. My sister and I had to be very careful when we went to Villepinte because it was becoming more and more dangerous. From the moment we had to start keeping a low profile, I began to feel less at home. I didn’t understand why we had to hide. Because we were born Jewish? But it was just a religion like any other, wasn’t it?

In October 1940, the Vichy government announced new restrictions on the Jewish population in the occupied zone; Nazi policy drastically reduced “Jewish participation” in the medical and legal professions in particular. Jewish patients were no longer admitted to public hospitals, judges in German courts could no longer cite legal arguments or judgments made by Jews, Jewish officers were expelled from the army, and Jewish medical students were no longer allowed to sit their exams.

Louise, as a Jew, was subjected not only to restrictions, but also to bullying (people in power made life difficult for newcomers in the military and in schools). Such restrictions and bullying were commonplace. New legislation was published regularly.

The Germans took over the north of France and when they arrived in Paris, they began to persecute the Jews. This meant that we had to try to remain invisible and not draw attention to ourselves. New legislation was introduced as well, meaning that we had fewer and fewer rights and we were not allowed to have certain things or go to certain places. At that time my family and I were still living in our apartment on Rue du Moulin Vert.

In 1942, my sisters and I were obliged to wear the Star of David, as were all other Jews. My parents did not have to wear it because they were Turkish subjects were therefore protected by Turkey.

I did not really understand why we had to wear the star and hide. I became more and more afraid. There were rumors that Jews were being rounded up. I still went to school sometimes, but it wasn’t like before. Most of my friends no longer talked to me because I was wearing a star. I spent more time with other Jews and a few of my old friends. Losing friends and being shunned like that hurt me a lot.

I lived through that for four years. If I went to school, I had to keep a low profile. Round-ups happened more and more frequently, including in our neighborhood. Fortunately my family was not arrested, but we lived in constant fear.

On June 6, 1944, we heard that the Normandy landings had taken place, and this news gave us a glimmer of hope. We believed that the war would soon be over, we really thought this was the end of it all.

Unfortunately, on July 7, my father was arrested at work. We then sought refuge in my aunt’s apartment in Villepinte, but on July 12, 1944, my sisters and I were arrested after someone reported us. My mother and my aunt were not arrested because they were Turkish citizens. The police only took we three children, Victoria, Bequi and me, even though I was blond and had blue eyes.

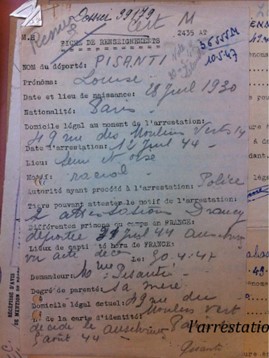

Information sheet about Louise’s arrest

Louise does not know who had reported her to the authorities. On the information sheet about her arrest, it says that she was arrested for “racial reasons”. This means that she was arrested because she was Jewish. She was deemed to be an “Israelite”, which meant a member of the Jewish community.

A record of her arrest was made on July 12. It also states that she was arrested by the police and taken to the Drancy internment camp. This information sheet about her arrest was compiled by her mother in 1947. It contains all the information about her arrest and the places she was sent to (Drancy and Auschwitz).

When I was arrested, I was afraid because I had to leave my parents, even though I was with my two sisters and some other children. The police put us in a detention facility. We stayed there for a few days and then most of us were transferred to the Drancy transit camp. I arrived at Drancy on July 17, 1944, five days after I was arrested. It was very big, dark and dirt and there was a nauseating smell that caught our throats. This place was simply terrifying. In Drancy transit camp, we already felt that we were living in hell, but it was nothing compared to what we were to experience later on. We were given very little food, we never had any proper meals and everyone was hungry all the time. We were surprised to find our father was there too, just as we heard that we were going to be sent to Pitchipoï.

Drancy transit camp

After spending a week in Drancy, it was my turn to leave, along with hundreds of other people. No one knew where we going. We left Drancy by bus and were taken to the Bobigny railroad station. People said that we were going somewhere to work, but nobody really knew. I was really scared. When we got there, soldiers loaded us all into cattle cars. I left Bobigny station on July 31, 1944.

Convoy list Bobigny station

They crammed us into cattle cars, and we were all pressed up against each other. There were about 60 of us in each car. There was very little room. I was wedged in with the other deportees beside me. We had to stand up and take turns to rest from time to time. It was extremely hot as it was the middle of summer. And not only that, but there wasn’t even an opening, just a tiny window, so the air was hard to breathe. There was just one bucket in our car for us to relieve ourselves during the journey. Adults would hold a blanket or a piece of clothing around themselves in order to provide a minimum of privacy. This was the time that we lost whatever dignity we had. We had no privacy at all. When I had to relieve myself, I felt terrible. I felt so humiliated, we were treated like animals. And the smell from the bucket was really nauseating. We did stop a few times, however, and during these short breaks someone could empty the bucket. The conditions in these wagons were inhumane, and all the more so because we had no food or water either. I was hungry and thirsty, as was everyone else, but I didn’t really complain. Some people were shouting and crying. The smell was unbearable. Some of the deportees around me even died. That made me wonder if I would survive it myself. I was only looking forward to one thing: the end of this journey, that it would not go on forever, to the end of this hell. I still didn’t know where I was going or why. I was humiliated and had been stripped of all my dignity. I felt abandoned and miserable, despite being with my sisters and my father.

The journey took about two nights and three days. Finally, the train stopped once and for all. We knew we had reached our final destination when we were yelled at to get off, surrounded by barking dogs. We all jumped out of the car. There were no steps to get off and it was a long way down. The old men who couldn’t get down were beaten. The SS officers shouted orders that we didn’t understand, but if we were unfortunate enough not to react quickly, they hit us. We were treated like dogs. There was also a foul smell, a stench of burned flesh and excrement.

Louise and the other deportees did not realize it at the time, but they were at the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

Auschwitz was a labor camp, where the deportees were forced to work, while Birkenau was an extermination center. Most of the deportees were killed in the gas chambers and then their bodies were burned in the crematorium.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp

After we got off the train, the deportees all moved forward and I followed them. The guards began to carry out the selection. They separated us into different groups: women and children on one side, men on the other. I was sent to stand in a line with the children and the seniors, which meant I was separated from my sisters and my father. I had no idea why I was in that line. We were marched to a forest and then taken to a place where we had to take off all our clothes. I got undressed along with everyone else. I felt humiliated again, just as I had in the wagon when I had to relieve myself. I felt ashamed to have to undress like that in front of strangers. I still didn’t understand what was going on. Then they took us all into a room that looked like a huge shower room. At this point, besides being humiliated, I was scared, really scared. I still didn’t understand what was going to happen to me and I could never have guessed. The guards were much more brutal here too, and then they locked us in. I was so frightened and I started to cry. Everyone around me was feeling the same way. I couldn’t understand what I was doing there. Then I stumbled and fell to the ground. I never imagined, when I went into this shower-like place, that I would not make it out alive.

That was how Louise died, killed in a gas chamber, at the age of 14. Her chances of being selected to work in the camp were minimal. She died afraid and confused, alone, without any of her family or loved ones. She never got to say goodbye and farewell to them. She was just a child. Afterwards, her body was taken away with all the others and burned in the crematorium.

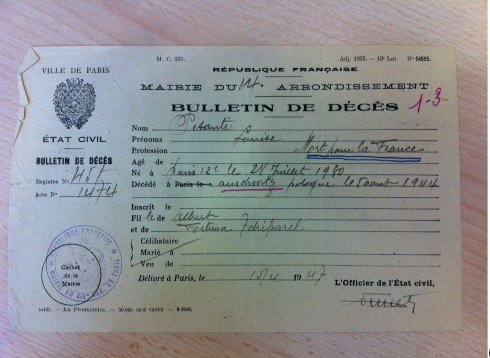

Death certificate

On Louise’s death certificate, it states that she died on August 5, 1944. In reality, however, no one knows the exact date of her death. The French authorities counted 5 days from the time she left Drancy, which is the place where she was last seen alive by people who could testify to the fact.

A few years later, on September 11, 1951, her mother made several official requests to the French authorities. As a result, Louise was recognized as having been deported for political reasons, was granted the title of ‘Political Deportee” and also that of “Mort pour la France”, or “Died for France”.

Louise’s mother was not deported and survived the war, as did her two sisters, Bequi and Victoria. Louise and her father Albert both died in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp.

Following a long and complicated administrative process, Louise’s mother was awarded 12,000 francs in compensation for the loss of her daughter. It must have taken the three women a long time to get back to a more or less normal life after the war. Their life was never the same again and they were mourning for Louise. The indemnity served as justice of a sort, but it would never be enough to compensate her mother for the loss of her daughter and husband.

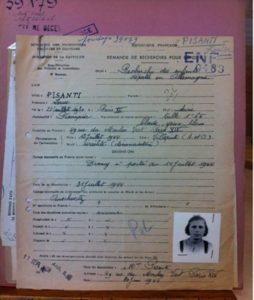

Request for research to be carried out on Louise Pisanti

Conclusion

Louise Pisanti died in a gas chamber in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. She was one of the people deported on Convoy 77, the last transport to leave Bobigny station. She died at the age of 14. Louise had no chance of surviving and living the rest of her life. She was killed in atrocious circumstances. She had been through a living nightmare since the beginning of the war due to the persecution of the Jews.

She was an innocent child who was killed simply because she was born Jewish. And sadly she was not the only one to suffer this sad fate. Six million Jews were murdered as a result of Nazi ideology.

Sources

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77.

- Witness statements from Béqui Pisanti, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, available on the Shoah Memorial website.

- Short biographies available on the Yad Vashem website.

- Books: Simone Veil – Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah; Ginette Kolinka – Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant – Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan – J’ai pas pleuré.

- Photos taken at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy.

Français

Français Polski

Polski