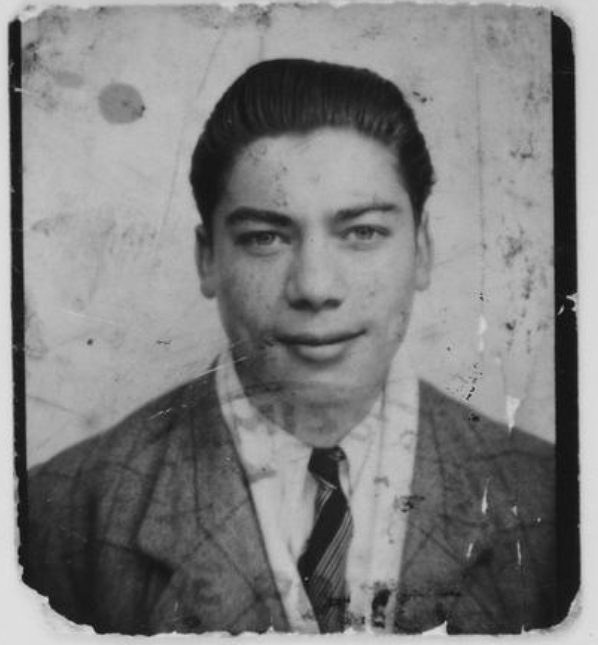

Maurice GRINBERG

Identity photo of Maurice, taken in around 1944 © Shoah Memorial, Paris

Maurice was born on May 24, 1927, in the 10th district of Paris. He was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 together with his mother, Esther Guittel Grinberg née Spatz, his older sister Rivka, known as Renée and his younger sister Monique. When he arrived in Auschwitz, was selected to enter the concentration camp for forced labor, was then transferred to other camps and disappeared sometime after February 1945 in the Tubingen area of Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

We were able to retrace Maurice’s life story with the help of the various historical records. In addition to writing this biography, we produced some maps in order to compile an “Atlas of the Grinberg family”, and recorded a series of podcasts. These are included throughout the biography.

You will find the Atlas, in French here.

The family emigrated to France from Eastern Europe

The first podcast report, in French:

Maurice’s father, Shil Grinberg, was born on January 16, 1904 in Bar, in Vinnytsia, which was then in the Russian Empire but is now in the Ukraine, not far from the Romanian border. He appears to have grown up a little further south, however, in Secureni in Bessarabia, in present-day Moldavia. According to the records, his parents were Leib (Louis) Grinberg and Freida Rothstein, but oddly, he also appears to have had or lived with a second family, Mendel and Chana Reider, who, along with their daughter Doudle, died while on a death march in 1943 [1]. According to his naturalization application, Shil had two younger brothers.

Shil arrived in France as a Russian refugee (he had a passport issued by the right of asylum department in 1924, which was renewed in 1930). He was a secondhand dealer at the Saint-Ouen flea market (and later became a delivery driver, but possibly not until 1941).

His mother was Esther Gittel Spatz (Schlank/Shank), who was born on December 16, 1902 in Siedlanka, a suburb of Lezajsk, a small town some 30 miles northeast of Rzeszow, which was then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire but is now in Poland. Her mother, Maurice’s grandmother, was Hinde Spatz, and her father was Zolme Schank.

Esther’s parents wanted to send their children “to America” in order to escape poverty and, more importantly, the pogroms. Her hometown of Lezajsk also got caught up in the fighting between the Russians and Austro-Hungarians between November 1914 and May 1915, which would hardly have enticed them to stay.

Below are two maps that chart their journey into exile.

Esther met Shil Grinberg in 1922 or 1923. He had arrived in France from Bessarabia or Moldavia, she from Poland. They were not yet 20, and both were hoping to emigrate to America (Esther had a sister in Brooklyn), but in the end, they stayed on in Paris. They met in a refugee “shelter” on rue Lamarck and then set up home together in a shanty-town in the Saint-Ouen flea market, an area in which many Jews from Eastern Europe lived. Between themselves, they always spoke Yiddish. They were naturalized as French citizens on December 4, 1933.

As a child, Esther had never been interesting in learning to read and write. “She was a savage,” her daughter Renée used to quip. She regretted it later in life, and insisted that her children did not follow her example. Renée, when she was around 6, began to read the newspapers to her and help her learn French. Esther never let her children speak Yiddish and only let them speak French at home, although when she said, “Kindlerkh, kimt shoyn!” they obviously understood that they had to come, and if she added, “Kimt zim Tish!”, they knew it was mealtime.

The move from the shanty-town to a low-cost housing development near Porte d’Aubervilliers

Shil and Esther with their daughter Rivbaka/Rivka/Renée in their shack

in the shanty town (in the late 1920s?) © Family archives

When Maurice was born in May 1927, they were living at 7 rue Saint-Laurent, in the 10th district of Paris. Shil officially declared himself to be the father the following day, and Esther declared herself to be both Maurice and Rivka’s mother on July 16, 1930, shortly before she and Shil were married.

Shil and Esther were married on July 22, 1930 in Saint-Ouen. They were then living 100 rue Jules Vallès: a street in the flea market, not far from what would become the Malik market in the 1940s. They lived in a neat, well-kept shack in what was known as the “zone”, a shanty town that had sprung up on the site of some old fortifications (now under the Paris ring road). The Grinberg family built up a network of work colleagues, neighbors and friends, including two other families from Eastern Europe, the Blumbergs and the Schlosses (or Szlos), whose children all played together.

Maurice’s father became a secondhand dealer, hunting for old objects in the nicer neighborhoods, initially with a handcart. Then, so he could sell larger pieces of furniture and earn more money, he bought a horse called KikI, and a horse-drawn cart. Later still, he bought a motor car, a Citroën convertible.

An old postcard of the rue Jules Vallès in the Saint-Ouen flea market

© Saint-Ouen municipal archives

According to the 1936 census, they then moved to 18 rue Charles Lauth, in the 18th district of Paris.

Here is a map of the area around rue Charles Lauth, in Porte d’Aubervilliers:

The Grinberg family in around 1939: they already had five children by then (from right to left, by age, oldest first: Rivbaka/Rivka/Renée, Maurice, Jeannette, Berthe and Simone) © Shoah Memorial, Paris

Rue Charles Roth was part of a low-rent housing complex built in 1935. Only French nationals were allowed to live there (this was one of the advantages of being naturalized citizens!). Their apartment had all “mod cons”: two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen with a coal-fired stove, a shower and a toilet.

The family was reasonably religious: Esther prayed every Friday evening. As for Shil, according to Maurice’s sister Renée, he was more of a Communist.

They had seven children in all: Rivbaka/Rivka/Renée (1925-2024), Maurice (1927-1945?), Jeannette (1930-2018), Berthe (1933-2019), Simone (1935), Daniel (1940) and Monique (1942-1944). As far as we are aware, there is only one photo of the family, and only the five older children are in it.

The first signs of trouble

In 1934, the family went on vacation to Poland, where they stayed with Esther’s sister and her family. Esther took with her the four children that she had at the time: Renée, who was 9, Maurice, 7, Jeannette, 4 and Berthe, who was just a year old. They did not book seats on the train, and the children had to sleep in the overhead baggage nets. The children remembered the Polish countryside vividly, as they had only ever known Saint-Ouen. Their grandmother was a wonderful woman, who still had four of her children with her, but the eldest sister had emigrated to America (where Esther had also intended to go), and another sister and two brothers had moved to Palestine.

They had to cross Germany on the way to Poland. They must surely have heard about what was happening to the Jews there.

Maurice became a mechanic

The courtyard of the Auguste-Balnqui school in Saint-Ouen © Saint-Ouen municipal archives

We do not know if Maurice continued to go to school in Saint-Ouen after they moved to Paris (both homes were about the same distance from the school on rue Blanqui), or if he then went to the boys’ school on rue Charles-Hermite, near rue Charles Lauth: we only know for sure that he went to school in Porte d’Aubervilliers. Either way, various records state that he was a mechanic when he was arrested.

Maurice’s father was rounded-up and disappeared

The second podcast report, in French

When war was declared in September 1939, the social welfare department moved the family out of the city: with so many children and their mother pregnant again, they were first in the queue. Renée was on vacation in the Allier department at the time along with some other children from Paris (but not Maurice?), and Shil went to pick her up and bring her back to Guerrouette, in what was then called the Loire inférieure department. Esther gave birth to Daniel in January 1940 in Saint-Nazaire. They then moved back to Paris, where not only the war but also the Vichy government’s antisemitic legislation made life increasingly difficult for Jews. The couple then went their separate ways, but not for those reasons: they split up for a while because Shil was unfaithful to Esther, although they got back together soon afterwards and had another baby, Monique.

The situation continued to worsen, and then in the summer of 1941, Shil was arrested. Perhaps, in their last few weeks together as a family, Maurice overheard his parents talking, and would surely have understood what they were saying in Yiddish: “Oy vay! Vous vet vern fin indz?“ Esther might have said ”Oh my! What’s going to become of us?” What if she discussed with Shil what they should do with the children? Send them somewhere safe? Keep them hidden? “Vous tit mit di kindas? Zoln mir zey yo avekshikn ahin? Ofn dorf?” Send them to stay in the country somewhere?

A recent photo of the café opposite the Cité de la Muette in Drancy

The French police arrested Shil in a café at Porte de Clignancourt during one of the roundups in August 1941, after which he was interned in Drancy camp. On June 23, 1942, he was deported on Convoy 3 to Auschwitz, where he remained for ten months. The Auschwitz-Birkenau records state that he died on July 24, 1942.

The family must have been aware of what happened to people who were sent to Drancy, and that the same was probably in store for them too. In fact, Renée and her mother, Esther, went to Drancy to “see” Shil. They had to wait in the bistro opposite the camp (no doubt the same one that is now opposite the Cité de la Muette) until the prisoners came out on the balconies, but as Renée later explained: “It was very difficult to communicate with them because the guards were so intimidating”.

With no income of her own and a family to support, Esther soon found it hard to make ends meet. She managed to secure an allowance from the U.G.I.F. (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews) [2] for her seven children, as well as ration coupons and a soldier’s pension (had Shil served in the army in 1939?). She had to sell off everything she had that was worth anything, such as the car Shil used for work.

The younger children were sent into hiding

In 1943, the younger children (except for the baby, Monique) were sent into hiding in Brittany, thanks to the assistance of Father Devaux from the order of Notre-Dame de Sion.

Two sisters who lived in Amanlis, near Rennes, took them in. In 1943, these two young women, who were themselves wards of the French welfare system, had decided to open a home for abandoned children in Janzé. The nuns from Notre-Dame de Sion placed six children from the Paris area with them. The social worker who brought the children to them explained that their parents had been deported and that they had no food ration cards. In late 1943, the shelter was moved to Amanlis. A local support network, made up of some farmers, a baker and Les Docks du Ménage, a Rennes-based firm, helped out and provided the food. Jeannette, Berthe, Simon and Daniel Grinberg were placed with two families in the village. Their older sister, Renée, took them there because Esther had too strong a Polish accent, so could not travel around without drawing attention to herself. Their lives were saved as a result, as were those of all the other children who were kept hidden in Amanlis. Renée, who was also deported but survived her time in the camps, went to collect them after she returned to France in May or June 1945.

However, neither Renée nor her mother found the strength to leave little Monique in Amanlis, either in 1943, at the same time as the others, or in late May/early June 1944, just before the Normandy landings: she really was still only a baby!

Maurice too was arrested and deported, along with his mother and two of his sisters

The third podcast report, in French

Esther and her other three children, Rivbaka/Renée, Maurice and Monique, were rounded-up on the night of July 8, 1944. Five men (militiamen, French police and Gestapo agents) arrived at their apartment, on the pretext of checking their identity papers, but then arrested them.

All four of them were taken to Drancy. Maurice was sent to room 4 on staircase 18, while Esther, Renée and Monique were put in room 2 with some other women. They remained there until July 31, 1944, when they were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77.

According to Renée, during the three-day journey to Auschwitz, Maurice tried to make his mother and sisters as comfortable as possible in the cattle car, and shared out the water. Whenever he could, he gave his mother a break by taking baby Monique in his arms, but Monique, who was distraught, tried to cling on to her mother. When they arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Maurice and his sister Renée were separated from their mother and little sister, who were sent straight to the gas chambers.

From Auschwitz to Natzweiler

Renée said in her testimony, which was recorded in 2006, that she met Maurice for the last time a few weeks after they arrived in Auschwitz. This was before she was sent to the Kratzau camp and before he too was transferred to other camps. They saw each other and spoke very briefly, not knowing that they would never see each other again.

We were able to find out what then happened to Maurice from records in the Arolsen archives.

When he entered the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on August 3, 1944, Maurice Grinberg (spelled Grinbert in the records) was assigned prisoner number B 3781. He was forced to work there until fall. On October 26, 1944, under the name Grimberger, he was loaded onto a transport to the Stutthof concentration camp, near Danzig in Germany, which was run by the Todt organization. He arrived there on October 28, 1944. On November 29, 1944, he was included in a convoy of 600 Jewish workers bound for the Hailfingen annex camp, near Tubingen, also in Germany, where the Nazis were building an airstrip. The camp was part of the huge Natzweiler concentration camp complex. The 600 Jewish deportees who arrived there from Auschwitz via Danzig were billeted in a hangar and assigned to work on the runway from late November to mid-February 1945. Three months later, 189 of them were dead: there was not only severe hunger, freezing cold temperatures, abuse and violence, but various diseases, which claimed the lives of around a third of them. Then, from February 1945 onwards, as the Allied troops were advancing towards the camps, the German guards forced the deportees to walk from camp to camp on what became known as the death marches, which increased the death toll even further.

Map of the Natzweiler-Struthof camp complex. The arrow points to the Hailfingen camp, where the SS was building an airfield © https://amicalenatzweilerstruthof.fr/camps-rattaches

Maurice arrived there on December 1, 1944, and was assigned the serial number 40621. From that moment on, there is no further trace of him.

He was officially declared missing in Paris on August 9, 1952, and a missing person’s certificate was issued.

Maurice’s death certificate was issued on April 12, 2011, after which it was entered into the civil register at the town hall of the 18th district of Paris. He was officially deemed to have died on August 5, 1944, which is clearly incorrect since we know that he spent time in Auschwitz and other camps and was still alive in December of that year.

Having become a French citizen by declaration in 1930, Maurice was regarded as a French national. In February 1949, the army concurred. Since he had not reported for duty when he was called up, he was classified as an “insubordinate soldier”. The military investigating judge, who Renée had notified that Maurice had gone missing, was unconvinced. He said he needed formal proof from the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs.

Maurice was posthumously granted the status of “Political Déportee”, in recognition of the fact that he had been deported on political grounds, i.e. that he was Jewish.

Notes

[1] This second family remains a mystery, but Renée and Jeannette Grinberg filled in testimonial sheets at Yad Vashem for these two people, stating that they were their granddaughters and great-nieces.

[2] The U.G.I.F. was founded in 1941 by the Vichy government at the behest of the Germans, and was supervised by the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives (General Commissariat for Jewish Questions). It was, among other things, responsible for helping Jews in need.

Sources

- File on Maurice Grinberg held by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service;

- File on Maurice held in the Arolsen Archives;

- Records available on the Amicale nationale des déportés et familles de disparus de Natzweiler-Struthof et de ses Kommandos website;

- Records held by the French National Office for Veterans Affairs and Victims of War;

- Paris archives (civil registry, census data, school records);

- Interview with Renée Nadjar née Grinberg, filmed in 2006 by Jérémy Nedjar;

- Records for various members of the extended family on the Yad Vashem website;

- Summary of a discussion between Renée Nedjar née Grinberg, Laurence Klejman and Muriel Baude on December 28, 2018 (with Renée’s handwritten corrections).

Thanks

We would like to thank Renée Nedjar’s son, Alain, and her nephews, Jacques Nedjar and Olivier Szlos, for their personal accounts and the many valuable documents still in their possession, which contributed greatly to this biography, and David Choukroun, who helped us trace the family of Renée Nedjar, Esther’s daughter, supplied Shil and Esther Grinberg’s naturalization file and helped us with our research.

Thanks also to: Claire Stanislawski at the Shoah Memorial in Paris and to the guides at the Shoah Memorial at Drancy; to Charlène Ordonneau from the Saint-Ouen municipal archives, who allowed us to explore the archives relating to the “zone” and the flea market; and to Macha Fogel of the French Yiddish Cultural Centre for giving us a brief introduction to the Yiddish language.

We would also like to thank Laurence Klejman for proofreading our biographies of the Grinberg family and providing us with a wealth of additional information, making them the most detailed we could ever have wished for!

Français

Français Polski

Polski