Necha GOLDSZTEJN

This investigation was carried out by the students from 9th grade classes C and D at the La Cerisaie middle school in Charenton-le-Pont in the Val-de-Marne department of France: Julie Adda, Yasmine Aliouane, Coumba Cissoko, Fatoumata Dabo, Elyanna Kaleba, Amira Smaali and Shaïly Tubiana with the guidance of their teachers, Nathalie Baron and Sonia Drapier.

La Cerisaie middle school, Charenton-le-Pont – 2021-2022

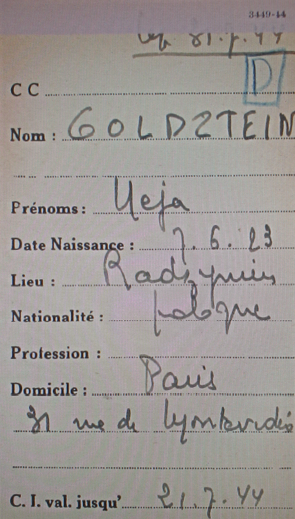

Our investigation into the life of Necha Goldsztejn began with a bundle of 48 documents that soon led us to the obvious conclusion: Necha was one of the survivors of Convoy 77, which left Drancy for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944.

We therefore set out to trace the story of her life. Our research was facilitated by our email exchanges with several members of her family, including her grandson Pascal, her niece Laurence and her daughter Jocelyne. We also had the opportunity to meet her sister, Georgette, and her fellow deportee, Yvette Levy.

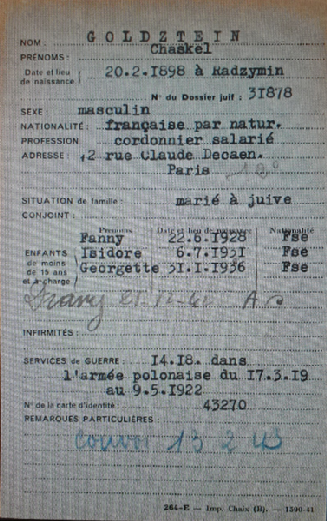

Our research was complicated somewhat by the different transcriptions of her first and last names from Polish to French: Necha or Neja for her first name and Golztein, Goldzteyn or Goldsztejn for her last name. For ease of use we have chosen to use the spelling given on her identity card.

We would now like to share with you Necha Goldsztejn’s life story.

I- A Polish family that moved to France

Necha Goldsztejn was born into a Polish Jewish family from Radzymin, a small Polish town in the Mazovian province located about 16 miles northeast of Warsaw.

Photograph of the rural village of Radzymin in 1930

Source: http://polishpoland.com/radzymin/

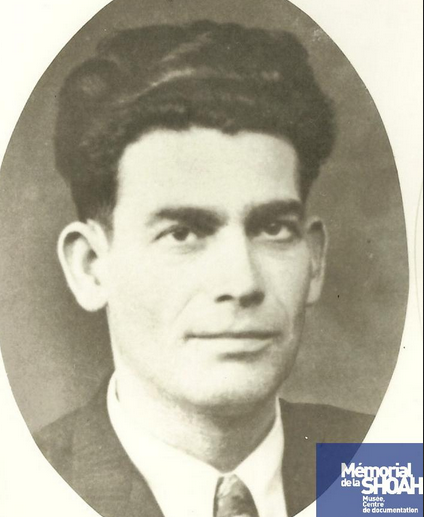

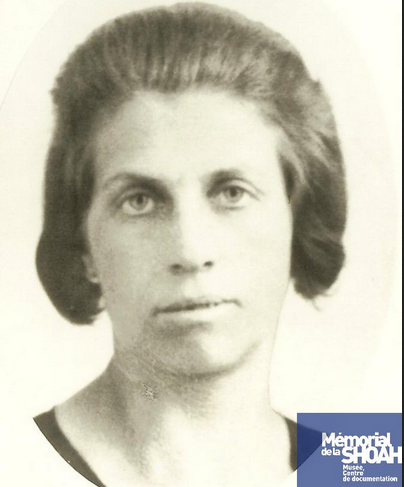

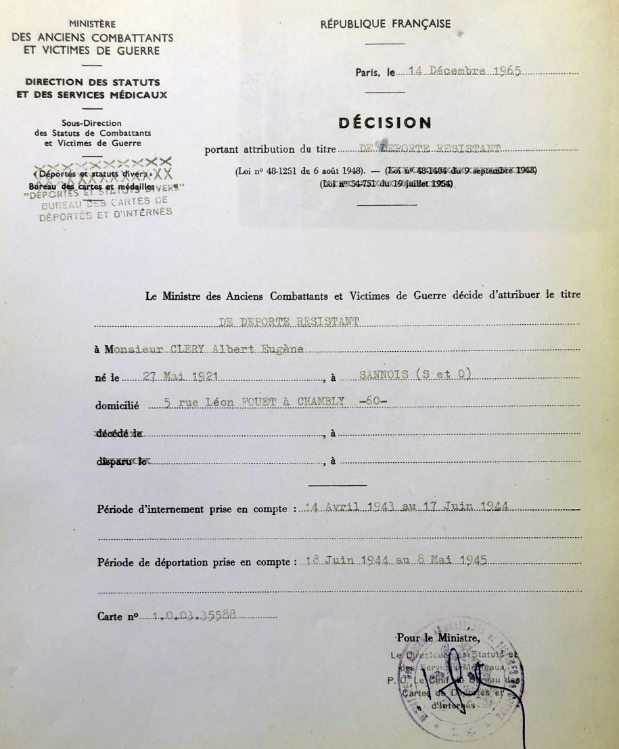

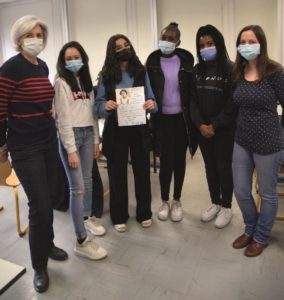

Necha’s parents were both born in Radzymin; Blima Jarzembek on 1 August 1897 and Chaskel Goldsztein on 20 February 1898.

They got married on March 3, 1919, although their first daughter, Marguerite (known as Marsza or Margot), was born on February 20, 1918.

Chaskel enlisted in the Polish army during the First World War and then again from March 17, 1919 to May 9, 1922. He moved to Paris alone at the end of 1922 when France was appealing to foreigners to help rebuild the country.

Blima and their two daughters followed him in 1924. It seems that Necha, born on March 2, 1923 in Radzymin, only met her father several months after she was born.

The family first settled at 30 passage Saint-Ange, in the 17th district of Paris, and then moved to 72 rue Claude Decaen, in the 12th district.

⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀⠀

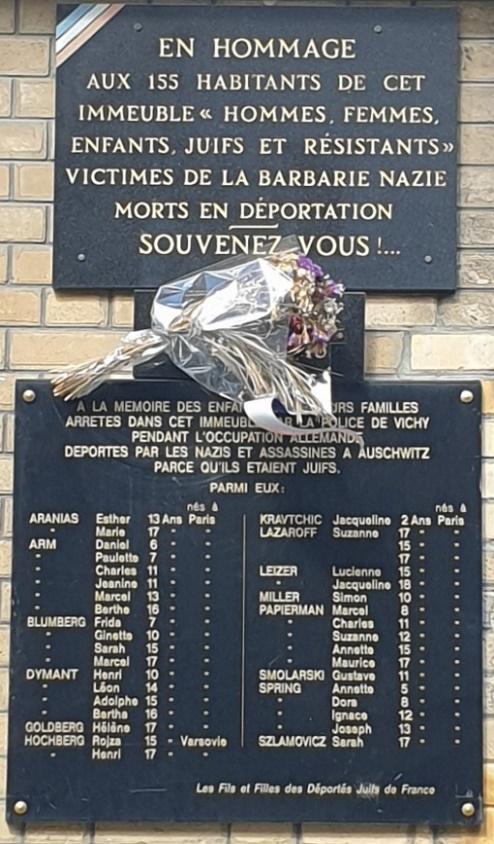

Apartment building at 72 rue Claude Decaen – 12th district of Paris (Photos: Nathalie Baron)

Chaskel worked as a shoemaker while Blima raised their five children. After Marguerite and Necha came Fanny, who was born in Paris on June 22, 1928, Isidore, born on July 6, 1931 and Georgette, born on January 31, 1936.

Chaskel, Blima and their two oldest daughters were naturalized as French citizens by decree on November 14, 1938 and kept their French nationality during the war.

⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀

Chaskel and Blima Goldsztein

Source: https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org

It was in their apartment on rue Claude Decaen that the French police arrested Chaskel and Blima on December 23, 1942, as a result of someone having turned them in.

The children, who were not at home when their parents were arrested, were alerted by a neighbor who suggested that they go into hiding. They initially took refuge with their sister Marguerite who was living at 85 rue du Faubourg Saint Denis and then went to stay in children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews). Fanny stayed at the UGIF centers on rue Guy Paty and rue Lamarck in Paris. As for Isidore and Georgette, they spent the war years with the Bruneau family in Parnes, near Gisors, in the Eure department of France.

The children were unaware that on February 13, 1943, their parents had been deported to Auschwitz, where they were killed in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived.

A record from the Paris Police Department

Shoah Memorial in Paris

II- Necha’s childhood

Necha was barely a year old when she arrived in Paris with Marguerite and their mother. She went to school in the 12th district, most likely at the Brêche aux Loups school, as far as her sister Georgette can remember.

Necha passed her primary school certificate on June 15, 1936. She then took childcare classes on the rue des Epinettes in Paris. At the age of 16 she got a job in a company where she learned to be an assistant accountant.

Necha in 1938, when she was 15

Source : Identity photo

After her parents’ arrest, Necha stayed in a UGIF center, run by a Mrs. Mortier, at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris. She continued to work as a secretary/assistant accountant, and it was at work that she met Paulette Cléry, who was to become her best friend and later her sister-in-law.

While staying in the home on rue Vauquelin, Necha shared a room with Yvette Dreyfuss (married name Levy) who told us that they soon became close friends. While Yvette was a member of the Girl Scouts, where she was known as “Gipsy”, she said that Necha was not.

You can read the biography of Yvette Levy, née Dreyfuss, on the Convoy 77 website here: https://en.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/yvette-dreyfuss/

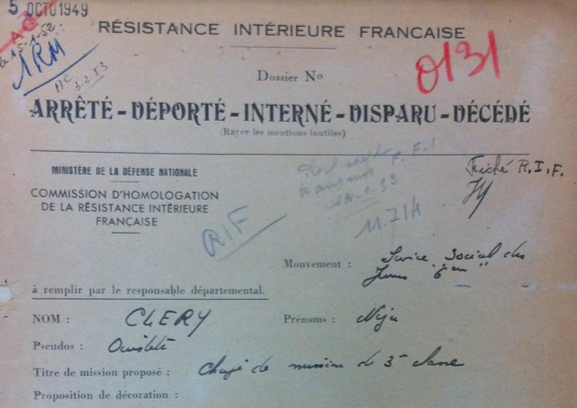

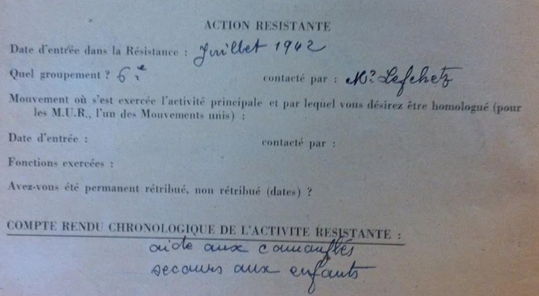

We have not been able to find out why Necha applied to be recognized as a resistance fighter under the alias of “Ouistiti”, as shown by the records. She submitted an application to be recognized as having “helped the camouflaged”, meaning people in hiding, and “helped the children” as a “3rd class officer” in the social service for young people known as “La Sixième” (The Sixth).

According to her daughter and sister, Necha never took part in any Resistance activities. This was confirmed by Yvette Levy, who was herself a member of “La Sixième” section of the Éclaireurs israélites de France, the Jewish Scouts of France. This was a movement that involved young French and immigrant Jews, which was allowed to operate until September 1942 and which focused on helping children.

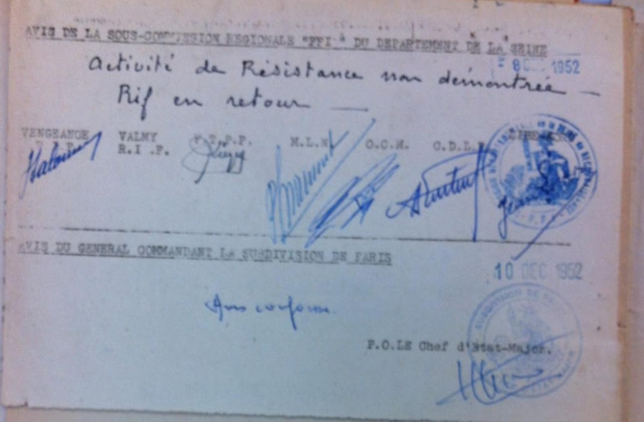

Necha’s request to be recognized as member of the FFI (French Forces of the Interior), which she submitted in 1950, was not successful. Did Necha submit this request because she occasionally helped the children who were staying in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, or might she have been influenced by the fact that her husband, Albert Cléry, was acknowledged to have been a member of the Resistance?

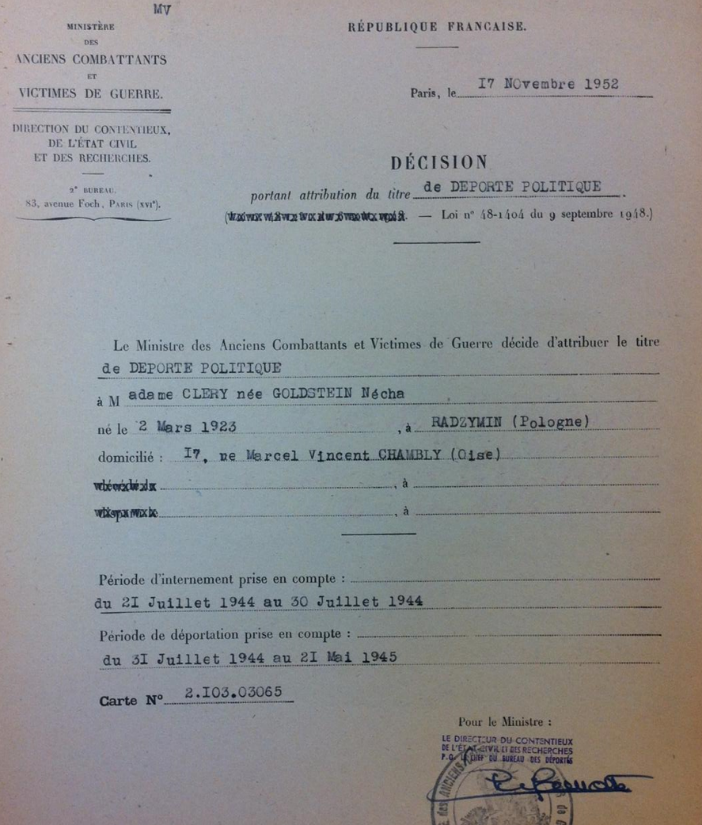

Given that she was arrested at the UGIF center on rue Vauquelin, there is no doubt that she was deported for political reasons and was therefore a “political deportee”.

Application for recognition as a French Forces of the Interior Resistance fighter

Application for recognition as a French Forces of the Interior Resistance fighter

Notification of refusal to grant the status of Resistance fighter

III- Arrest and deportation

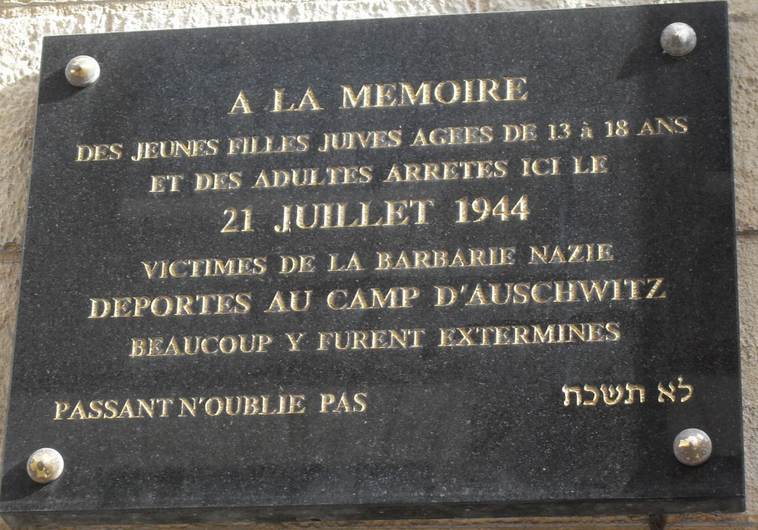

During the night of July 21-22, 1944, at around 5 a.m., the UGIF center on rue Vauquelin was the scene of a roundup organized by the Gestapo, following a failed attempt on Hitler’s life on July 20. Using retaliation for this attack as an excuse, the commandant of the Drancy camp, Aloïs Bruner, had all the children from the UGIF homes arrested. At the time, the Allies were only about 25 miles from Paris.

According to Yvette Levy, all of the children, the manager, Mrs. Mortier, and the janitor, Mrs. Kohn, were taken away before they even had time to get dressed. Mrs. Mortier had to go back to rue Vauquelin to collect some of their belongings because the girls were still in their nightgowns. We found Yvette Levy’s testimony about her arrest and deportation invaluable, since her journey from rue Vauquelin to Kratzau exactly coincided with Necha’s.

The building and the commemorative plaque at 9 rue Vauquelin, Paris

Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org

The children and staff were then taken to the Drancy internment camp, where they stayed from July 22 to 31, 1944. Yvette Levy told us that they were housed on staircase number 7, which now bears a plaque in honor of Max Jacob, who was also detained there. The older girls looked after the children, and tried to keep them occupied as much as possible. Necha, who was 16 years old by then, shared a bed with Yvette Levy and Evelyne Kann.

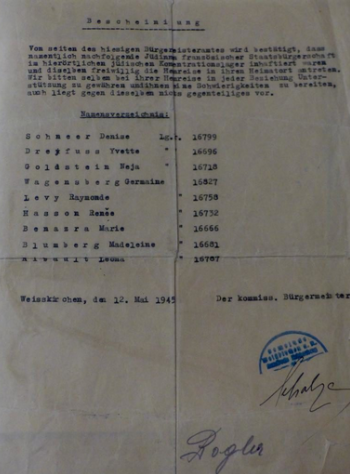

Source: Drancy records – Shoah Memorial in Paris

Convoy 77 was the last major transport of Jews from the Drancy internment camp. It left from Bobigny train station, bound for the Nazi extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, carrying one thousand three hundred people, including three hundred and fifty children under the age of 18.

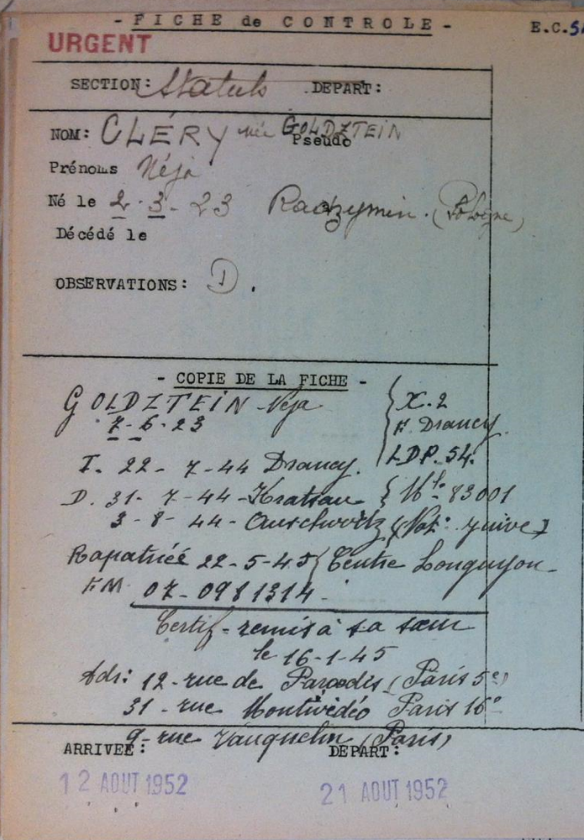

The journey to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp took three days and three nights. The living conditions during the journey were appalling, with 100 people crammed into each cattle car. During the night of August 2 to 3, nine hundred and eighty-six people arrived at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. As soon as they arrived, the selection process took place. Those who were deemed fit to work were separated from those who were not. In the case of this convoy, therefore, most of the people were killed in the gas chambers, including all of the children. As soon as they arrived, the selection process took place. Those who were deemed fit to work were separated from those who were not. In the case of this convoy, therefore, most of the people were killed in the gas chambers, including the children. The people who survived the selection were tattooed with a number, which added to the dehumanization process. Necha’s number was 16718. She was interned in Auschwitz Birkenau from July 31 to October 27, 1944.

Throughout her internment she remained with Yvette Levy, Evelyne Kahn, Denise Schneer and Germaine Wagensberg. Germaine and Denise also vouched for her in various post-war administrative procedures.

When they arrived at Auschwitz, Yvette Levy told us that they were quarantined because the Nazis were worried about the spread of germs. Necha, unlike many of her fellow deportees, never caught typhoid fever.

On October 27, 1944, Necha and her friends were sent to the kommando Weißkirchen bei Kratzau, located in the Sudetenland in northern Czechoslovakia, about 10 miles from Reichenberg. They stayed there until May 9, 1945, together with around a thousand other Jewish women. The camp was located in a small place called Weißkirchen, in an abandoned textile factory, about 2 or 3 miles from Kratzau.

Necha worked in a weapons factory making parts for pistols and rifles. She had to walk for an hour each day to get to the factory, and once there, she had to work continuously for twelve hours, day or night, alternating every other week.

Yvette and Necha did not work in the same workshop. Necha worked in a weapons factory and was assigned the task of painting. The deportees were given empty grenades which had to be polished and then coated with anti-rust oil before being painted. They were given a glass of skimmed milk every day to help prevent them from being poisoned by the chemicals they were exposed to. According to Yvette Levy, the deportees sometimes poured the milk into the paint to contaminate it.

Yvette Levy also remembers that the girls collected scraps of fabric from the workshop, persuaded a soldier to give them a needle and thread and then made bras for themselves. The female SS guards were so rough with the women that a foreman called them out because he needed them to keep working. They washed themselves as best they could at night, in a bucket of warm water.

This testimonial, which was found on the internet, gives an idea of what life in Kratzau was like for Necha: https://www.cercleshoah.org/spip.php?article705

The Kratzau camp was liberated by the Red Army on May 9, 1945. In her testimony, Yvette Levy reports that the Soviet soldiers did little to help the deportees, who were left to their own devices.

Denise (known as “Furet”, meaning “ferret”) went with Yvette to the town hall in Kratzau to ask the mayor for a pass so that they could return to France. They got a lift to Prague in a truck around the 10th of May and stole a cart to carry the weaker ones. They stole a pushcart to carry the weaker ones, while the others pulled and pushed it. They had nothing to eat. They went to the American zone, but no one paid much attention to them and they received little help. They set off on foot again and had to walk all the way to Frankfurt and then to the Longuyon reception center in Meurthe-et-Moselle.

From there, they took a train carrying army troops, and when they arrived at the Gare de l’Est station in Paris an officer pointed out bus, probably a Red Cross bus, which took them to the Hotel Lutetia in Paris, a gathering place for survivors. When they arrived there, they were not even given anything to eat or drink and they did not dare to ask.

It was Necha’s friend Paulette Cléry who collected her from the Hotel Lutetia. According to her sister, Georgette, Necha was barely recognizable and extremely thin.

Necha said very little to her family what happened during the war. Her children can only pass on the following points:

- while working in the weapons factory, Necha had access to a little hot water and was slightly better fed;

- One day, when Necha had been selected to be sent to the gas chambers, one of her roommates died during the night, so she pretended to be this other woman, which saved her life. Yvette Levy, however, has no memory of this incident.

Her sister Georgette also explained to us that the deportees sometimes used to try to slow down or sabotage the morning roll call by discreetly moving a few steps in order to falsify the prisoner count.

The pass issued by the mayor of Kratzau (Source: Yvette Levy)

Decision granting Necha Goldsztejn the title of “political deportee” dated November 17, 1952.

This document confirms the periods during which Necha was interned and deported.

Record of verification issued in 1952 detailing Necha’s journey through the deportation process, from internment at Drancy to repatriation to the Longuyon reception center in France.

IV- Necha’s return to France

When she got back to France, Necha stayed with her best friend Paulette Cléry in Chambly in the Oise department. It was during that time that she met her husband to be, Albert Cléry.

Necha also met up with her sister Fanny, who was staying with a family in the Val de Marne department, and then with her other sister Marguerite. Although Marguerite was married to a prisoner of war (Charles Rozlowski), she was arrested on July 21, 1944 and deported to the Bergen Belsen camp on Convoy 80. When she came back from the camps, Marguerite returned to Paris, where she became a shoemaker.

As for the two younger siblings, Isidore stayed with his foster family while Necha took in her youngest sister Georgette in order to avoid sending her to an orphanage. Both Georgette and Yvette told us about Necha’s will to live and how she remained cheerful, as can be seen from her smile in the photos below.

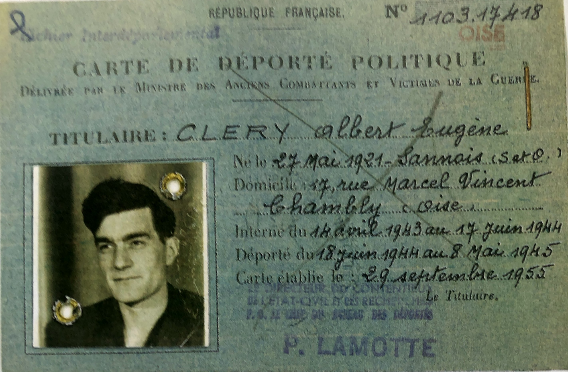

Albert Cléry, who was born on May 25, 1921 in Sannois, worked for SNCF, the French railroad organization, and was a member of the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (French Forces of the Interior) from October 1942 to April 1943. On April 14, 1943, he was arrested by the French police and sentenced to five years in jail and a fine of 40,000 francs for “political activity, distribution of tracts and anti-national activity”. He was then deported to Dachau in June 1944. In 1955, he was officially recognized as having been a “political deportee”, although this was rectified in 1965 when he was granted the status of “deported Resistance fighter” for a number of activities including “transporting explosives”, “distributing tracts” and “helping patriots to escape”.

Albert Cléry’s “political deportee” card, issued in 1955

Certificate stating that Albert Cléry was recognized as a “Deported Resistance fighter “ in 1965

Photo taken at Necha and Albert’s wedding on October 6, 1946 – Family archives

The girl on the bottom left of the group is Georgette, then the third from the left on the bottom row is Fanny, while Isidore is on the top left. Marguerite is not shown.

It should be noted that the official spelling of the family differs between family members. It is:

– Goldsztein for Necha’s parents and her oldest sister, Marguerite

– Goldsztejn for Necha (which is spelled Necha in Polish and Néja in French)

– Goldztejn for her sisters Fanny and Georgette and for her brother Isidore, all three of whom were born in France.

Necha Goldstejn’s family tree

Necha and Albert were married on October 6, 1945. They had six children: Pierre, Andrée, Martine, Jocelyne, Dominique and Jean-Marc, who then became parents themselves. The grandchildren are not shown in the above family tree.

Necha worked as an assistant accountant until the birth of her first child, Pierre on July 24, 1947. She raised her sister Georgette and also her niece Chantal, Marguerite’s daughter, from birth to the age of eleven since her parents were living in too small a house. Albert was a metalworker for the French railroad organization, SNCF.

In 1952, Necha was granted the status of “political deportee”. However, despite making several requests, she was never acknowledged to have been a Resistance fighter.

Necha gave a few testimonials in schools, but she was mainly involved in the Oise section of the FNDIRP (Fédération Nationale des Déportés et Internés Résistants et Patriotes, or National Federation of Deported Resistance Fighters and Patriots), of which she was the secretary. She kept in touch with several former friends who were also deported, including Yvette Lévy, whom she met again during meetings and on trips organized by the FNDIRP, such as from Warsaw to Nancy via Vichy (see photos).

Georgette explained that in 1978 she had gone on a remembrance trip to Auschwitz with Necha, during which they had met Yvette Levy. It was Yvette Levy who provided us with the following photo, which was taken at the time.

Warsaw – 1978

Source: Yvette Levy

Necha died on March 29, 1999 in Beaumont sur Oise in the Val-d’Oise department of France. She had been sick for some time and passed away in hospital in the presence of her family and her friend, Yvette Levy.

Survivors’ reunion – Nancy, France, May 9, 1993

Source: Yvette Levy

A get together in Nancy – late 1970’s

Source: Yvette Levy

A reunion in Vichy – date unknown

Source: Yvette Levy

We would like to thank everyone who helped us in our research.

This biography does not include all of the records that we have, since there are so many of them. They can however be made available to any of our readers who wish to see them.

On a similar note, if while reading this biography, which is inevitably incomplete, anyone who knew Necha should remember anything about her or has any anecdotes to share, we would be delighted to hear from them.

Our main sources:

- file relating to Necha from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, kindly provided by Convoy 77

- Shoah Memorial in Paris: various records unearthed with the invaluable assistance of the archivists

- family rerecords kindly provided by Pascal, Necha’s grandson, Laurence, her niece, and Jocelyne, one of her daughters, who also shared their memories of Necha

- the testimonies given by Georgette and Yvette, both of whom we were privileged to meet

- file relating to Albert Cléry from the Ministry of Defense archives

- civil status records from the Chambly town hall

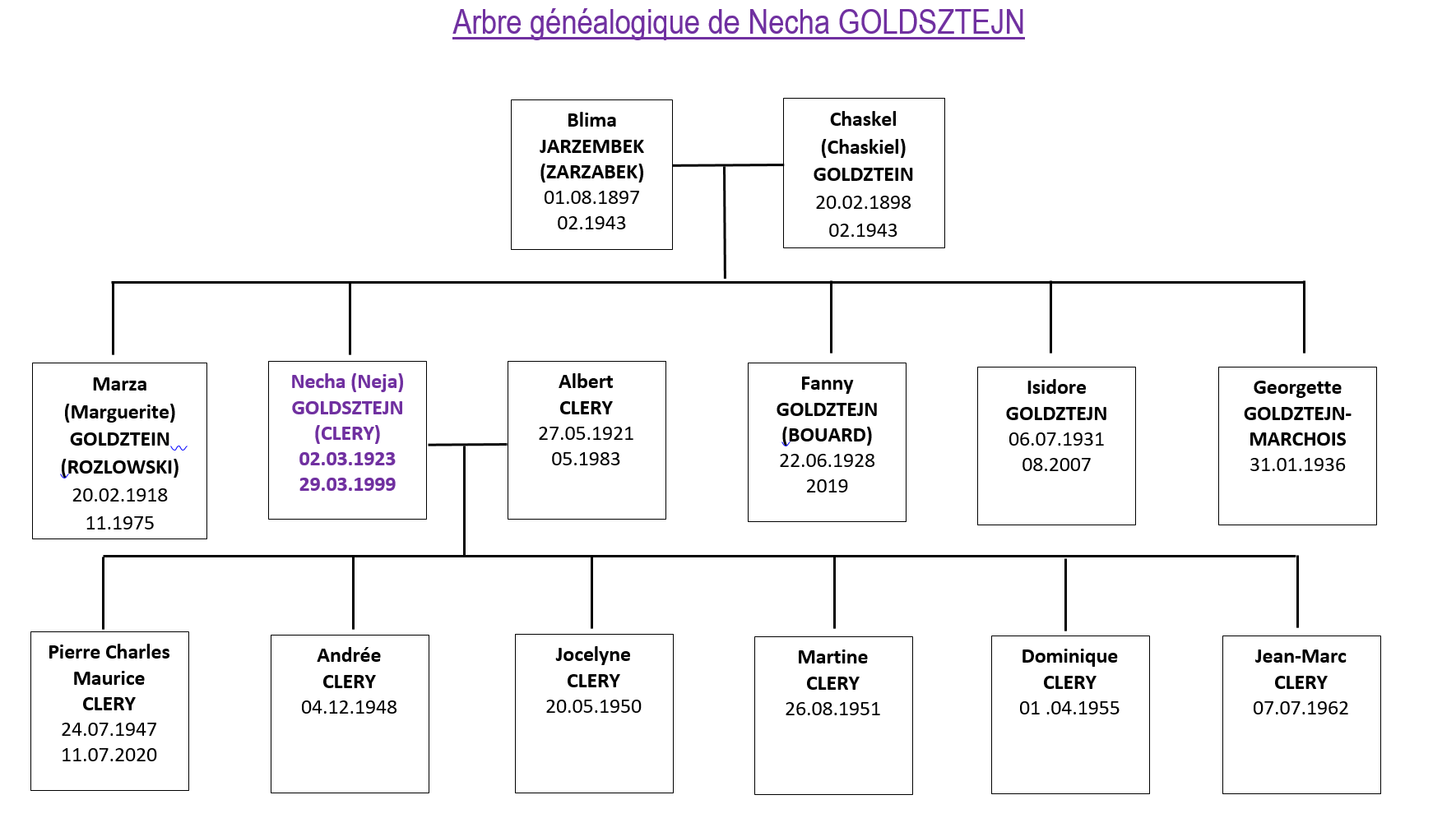

The authors: Julie Adda, Yasmine Aliouane, Coumba Cissoko, Fatoumata Dabo, Elyanna Kaleba, Amira Smaali and Shaïly Tubiana, 9th grade students from classes 3C et 3D at the La Cerisaie middle school in Charenton-le-Pont.

Their history teachers: Nathalie Baron et Sonia Drapier

⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ ⠀

March 23 2022 – Amira and Elyanna meet Georgette in Paris

May 23 2022 – Yasmine et Shaïly meet Yvette in Paris

Julie, Amira, Fatoumata and Elyanna with Ms. Baron and Ms. Drapier on either side

Source: Charenton Magazine, March 2022

Français

Français Polski

Polski