NICO DASSAS (1913-1999)

This project was carried out by the 9th grade students from class C at the Hague Dike secondary school in Beaumont-Hague, in the Manche department of France: Jade Delalande, Mathilde Raimbeaux, Julie Plassart, Evan Jaunet, Melissa Aimard, Faustine Noury and Raphaël Robillard.

Their teacher, Ms. Cécilia Varin, decided to take a different approach to teaching history, in particular what happened during the Holocaust, by focusing on the life story of one man, Nico Dassas, and his family.

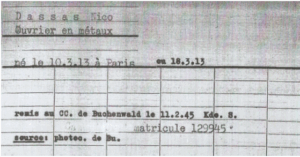

NICO DASSAS, ONE OF THE 1306 PEOPLE DEPORTED ON CONVOY 77

Nico Dassas, a man fiercely determined to live, a resilient individual, a horrific experience: a remarkable story of survival.

I) Nico Dassas’ family

A) The paternal side of the family

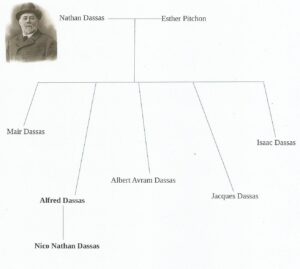

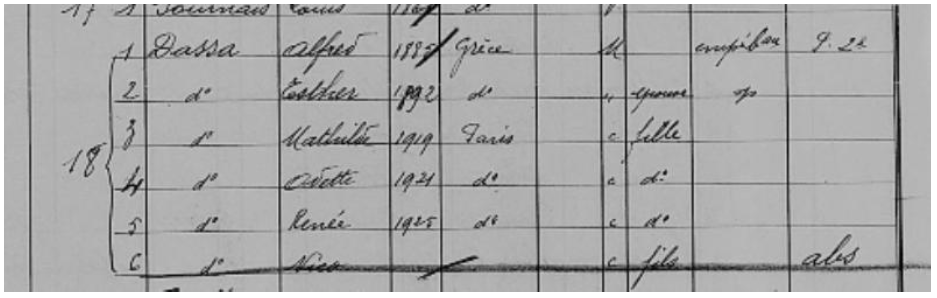

The paternal side of the family tree

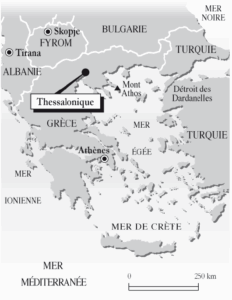

Nico’s father, Alfred Dassas, was born on May 19, 1885. His parents were Nathan Dassas and Esther Pitchon, both of whom were born in Salonika (now Thessaloniki), in Greece.

Map of the area where Nico’s father lived.

Source: Geographical atlas, published by Nathan, 2019

Photograph of Salonika (late 19th century).

Source: Photo exhibition “Salonika, Jerusalem of the Balkans” Marais-Louvre non-profit organization

Salonika was in the Ottoman Empire in those days. It is now Thessaloniki, in Greece.

In Ottoman times, the Dassas family were members of the Sephardic Jewish community..

The Sephardic Jews were originally from Spain and Portugal. After Queen Isabella of Castile signed a decree expelling them from Spain in 1492, Nico ‘s ancestors were forced to leave Seville and emigrated to the more welcoming city of Salonika in the Ottoman Empire; others chose to migrate to North Africa, the Middle East, Italy or the Netherlands.

Nico’s father, Alfred, migrated to France in 1912, together with his four brothers. He was 27 years old at the time. They all found work soon after they arrived.

His oldest brother, Maïr, worked as a butcher in the 11th district of Paris. Albert and Jacques were accountants and Isaac was a salesman in the 10th district.

All five brothers settled in Paris. Albert was the only one who became a French citizen, which he was entitled to do because he had volunteered to serve in the French army.

B) The maternal side of the family

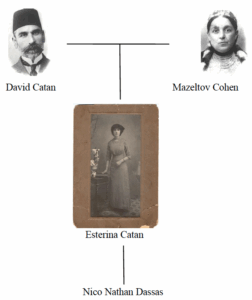

The maternal side of the family tree

Nico’s maternal grandparents were David Catan and Mazeltov Cohen. They had three daughters, Diamante, Lina and Esterina, who was Nico’s mother.

Esterina was born on July 17, 1888.

She lived with her parents in Salonika.

Esterina, like Alfred and his brothers, moved from Salonika to France for a number of reasons.

In the late 19th century, the Jewish community, which made up the majority of the population of Salonika, known as the “Jerusalem of the Balkans”, was well integrated into the city’s socio-economic life. Jews were actively involved in trade, manufacturing, banking and the professions.

However, between the end of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century, changes in the Ottoman Empire brought with them much uncertainty, which prompted many Jewish families to move elsewhere.

The Ottoman Empire, which had long been protective of Jews, began to lose its influence in the region. Inter-community relations were becoming increasingly tense, and there were rumors of war with the Balkan states. David Catan must have felt the effects of these developments.

Meanwhile, many young Jews had been educated in international schools, which catered for students from a wide range of backgrounds, and found France and other Western countries an attractive proposition.

David Catan decided to send his daughters to Western Europe. He had contacts in Belgium , so he sent Diamante and Lina. Esther, who had studied at the French high school in Salonika, was fascinated by French culture and the freedom that France was renowned for. She did not want to go anywhere else, so her father agreed.

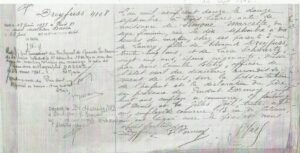

Did Alfred and Esterina meet in France? Or did they know each other already? All we could find was their marriage certificate, dated June 4, 1912. At the time, Alfred was a travelling salesman and Esterina was not working.

II) NICO’S LIFE BEFORE HE WAS DEPORTED

A) Childhood and adolescence

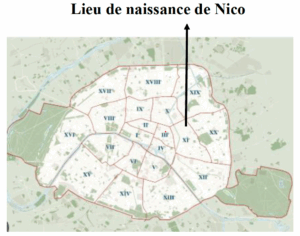

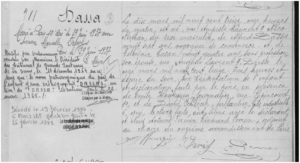

Alfred and Esterina’s first child was a son: Nico Nathan Dassas, who was born on March 10, 1913 on rue Auguste Laurent in the 11th district of Paris.

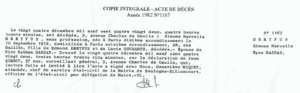

Nico’s birth certificate,

Source: Paris city archives

Esterina and Alfred went on to have three daughters:

- Mathilde, born on September 2, 1919 in Paris, and went by the name of Linda,

- Odette, born on June 24 1921,

- Renée, born in 1925.

Family tree

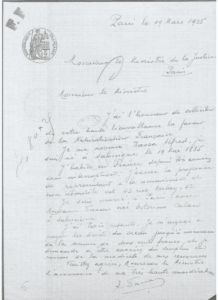

Alfred and Esterina applied to be naturalized as French citizens on June 1, 1925. The reason they gave for doing so was that their children had all been born in France.

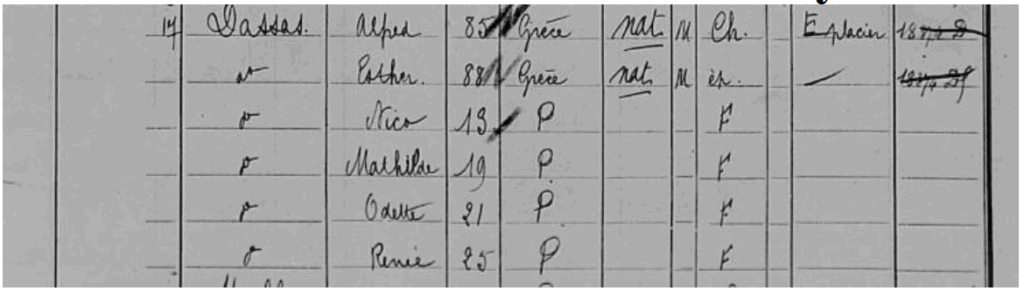

They were both granted French nationality (see the 1926 census record).

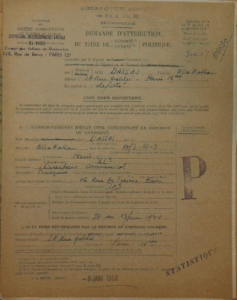

Naturalization application, Source: Ministry of Justice, French National archives

Source: Ministry of Justice, French National archives

Alfred was then working as a bookeeper for a Mr. Denforado, a milliner, at 47 rue d’Aboukir. He earned 1000 francs a month.

The family lived in an apartment block at 42 rue Meslay. It is important to note that the building at had a second entrance, on boulevard Saint Martin.

Nico grew up alongside his three sisters, who Nico’s sons described as “supportive, energetic and courageous young women, the very essence of life, freedom and happiness”.

1926 census record for 42 rue Meslay, Source: Paris city archives

As a child, Nico went to the local elementary school and then to the nearest high school, the Turgot high school in the 3rd district of Paris.

Photograph of the road on which the Turgot high school is located,

Source: photo kindly provided by the Turgot high school

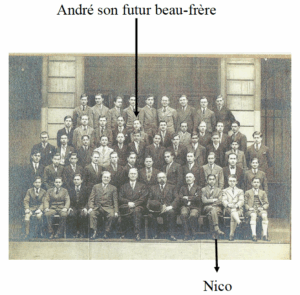

It was there that Nico met André Dreyfuss, whose sister he later married. They soon became great friends. Nico was a keen student, who always tried to get the highest marks in his class.

Class photo from the Turgot high school

After graduating from high school, he went to the ESCP, the leading business school in Paris.

B) Nico’s life before he was arrested

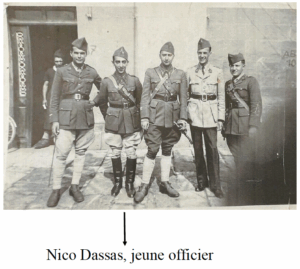

Nico volunteered to join the French army before he was called up, and was drafted into the 21st infantry regiment in October 1932. He started as a private, then became a cadet officer, and was promoted to second lieutenant in September 1933.

Photograph of Nico Dassas as a young officer. Source: Family archives

In the 1930s, Europe, including France, got caught up in the Great Depression that had begun in the United States in 1929. The French economy was hit by rising unemployment and a severe financial downturn. In response to this situation, extreme right-wing political groups, including the Nazi Party in Germany and the Ligues in France, began to emerge. Such groups voiced anti-government, xenophobic and anti-Semitic opinions.

How did Nico feel about the tense atmosphere that was no doubt apparent in the streets? Had he already begun hearing anti-Semitic slurs?

Between 1933 and 1936, he began his professional career with a footwear manufacturer, the Bata group, and made several trips to Czechoslovakia to visit the corporate headquarters. He was no longer living in the family home at the time, as evidenced by the 1936 census.

At the same time, as an army reservist, he continued his military training, and took two one-month courses in August 1935 and March 1937. He was appointed reserve lieutenant in August 1937.

The 1936 census of 42 rue Meslay. Source: Paris city archives

In 1936, Nico’s father died, leaving him the only man in the family. As such, he found himself responsible for supporting his mother and three younger sisters.

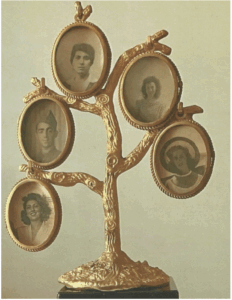

Family photo tree, minus Nico’s father

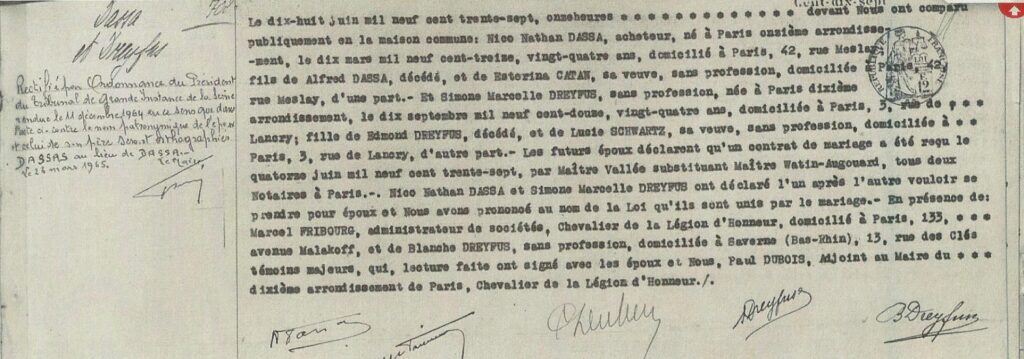

On June 18, 1937, Nico married Simone Marcelle Dreyfuss (his friend André’s sister). On Sunday June 20, they said “I will” at the synagogue on the rue de Notre-Dame de Nazareth. He and his wife were both 24 years old. According to their marriage certificate, Nico was working as a buyer, while Simone was not working at the time.

Nico and Simone’s wedding photo

Simone and Nico’s marriage certificate. Source: Paris city archives

Simone’s family

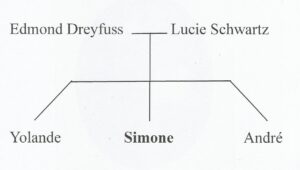

Simone’s family tree

Simone’s father was Edmond Dreyfuss, born on October 16, 1877 in Schweinheim, in the Alsace region of France. His parents were Lucien Dreyfuss, a trader, and Sarah (née Kahn).

They were Ashkenazi Jews, which means they came from Central and Eastern Europe. Ashkenazi Jews often lived in countries such as Germany, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, Hungary and Lithuania.

Simone’s mother was Lucie Schwartz. She too was born in Alsace, in 1887.

Edmond and Lucie

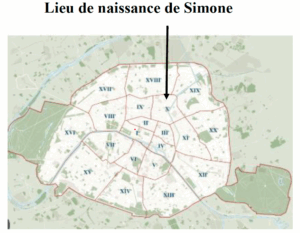

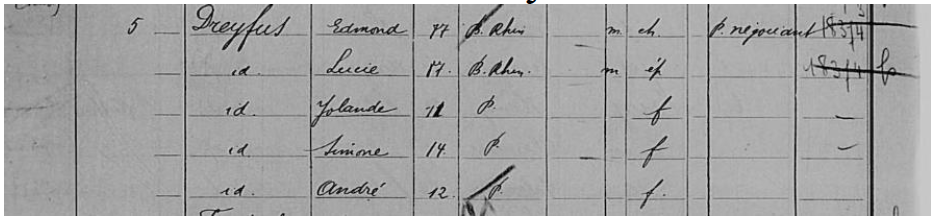

Edmond and Lucie had their first daughter, Yolande, in 1911. Next came Simone, who was born on Septembre 10, 1912, followed by a boy, André, in 1914.

Simone’s birth certificate. Source: Paris city archives

The Dreyfuss family lived at 3 rue de Lancry, in the 10th district of Paris. According to the census, the father was a merchant.

1926 census record for rue de Lancry. Source: Paris city archives

In May 1938, Nico and Simone had their first son, Gérard. He was born in Paris.

In 1939, Nico registered to vote in Faubourg Montmartre, in the 9th district of Paris. He was living at 36 rue de Trévise at the time, and described himself as an “accountant”, or “bookkeeper”.

Nico’s sisters, Mathilde and Odette, both worked in a little store on rue d’Aboukir.

On the international front, the news was bleak. In 1938, during the Munich Conference, Germany annexed the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia, but neither France nor the United Kingdom objected. Fearful of another confrontation, most European democracies opted instead for appeasement.

Nico must have been aware that Europe was on the brink, but he could hardly have imagined the danger that was in store for him and his family.

When war broke out, all that changed.

Odette stayed on in Paris, but Mathilde, who had studied at the Paris Opera, was offered a position with the Monaco Opera.

Nico, who was still a reserve lieutenant, was called back to the barracks at Courbevoie on August 23, 1939. This time, he was assigned to the 5th Infantry Regiment. On September 2, his regiment went to war.

He served during the “phony war”, which was brought about by the Germans threatening to invade the north east of France. The French army waited behind the Maginot Line for several months, but were never involved in combat. Nico was granted ten days’ leave in March 1940, much to his family’s delight. When the Germans invaded France in May 1940, he was seriously wounded by a bullet to the stomach. In a note to his wife, he wrote: “…having wanted to be brave, although not reckless, I took a slug from the Germans…”.

Nico was evacuated to hospital in Epernay, in the Marne department of France, and then transferred to Bordeaux, in the south west of the country, where, during the exodus and despite the difficult travelling conditions, his wife Simone managed to join him. When he was moved to the hospital in Carpentras, in the Vaucluse department in the south east of France, she followed him again.

During this period, he was awarded the French War Cross for his outstanding bravery in the field.

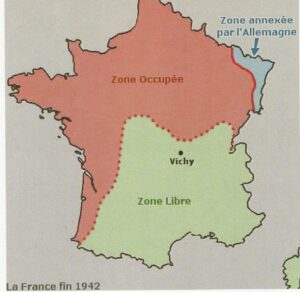

On June 22, 1940, after the German army’s lightning offensive, Marshal Pétain signed the armistice between France and Germany. This came as a terrible shock to Nico and his wife.

France was then divided into two “zones”: the “occupied” zone and the “free” zone. Germany occupied the northern part of France and the Atlantic coast, while the southern half, run by the French government, remained “free” until November 1942. However, this still did not mean that the Jews were free.

Map of France after the armistice. Source: History-geography textbook, Hatier collection

After a few months convalescence, Nico was deemed strong enough to return to service. He was assigned to the Orange regiment as head of an administration center. However, under the Vichy regime (so named after the town in which the government had been based since July 1940), he was demobilized in Avignon in January 1941.

France began collaborating with Germany on October 24, 1940. The meeting between Marshal Pétain and Hitler in Montoire did not bode well for Jews living in France.

The meeting between Pétain and Hitler in Montoire in Octobre 1940, Source: Radio France

The Vichy regime became authoritarian, collaborationist and anti-Semitic. As a result, Jews in France faced similar persecution to those in other Nazi-occupied countries.

In October 1940, the Vichy government enacted the first decree on the status of Jews.

The headline in the French newspaper Le Matin on October 19 1940. Source: Herodote.net

Jews were forbidden to work in the legal, teaching, and administrative professions , and from being in the military. They were also barred from many independent occupations, such as owning their own business.

Nico’s former employer, Roger Bellon, offered him a job in Paris, but obviously, in the circumstances, Nico chose to stay in the free zone. In March 1941, he took up a job as a bookkeeper in Avignon. Mr. Bellon made it clear from the outset that the job was well below his pay grade, but Nico explained that he had to support his family. It was wartime. What with the German occupation and the French government collaboration, Nico, who was French and Jewish, found himself in a precarious position that left him little room for maneuver.

That same year, 1941, his second son, Claude, was born in Orange, in the Vaucluse department of France. Both boys were raised in keeping with Jewish tradition, and both were circumcised.

Meanwhile, the Vichy government pressed ahead with its anti-Semitic agenda, and carried out its first roundup in Paris.

In May 1941, 6,500 Jewish men living in the Paris area were sent a summons printed on green paper. They were requested to report to one of several places in order to review their status. In reality, this was a set-up. They were arrested as part of what became known as the “Green Ticket roundup”. 3,700 foreign Jewish men were arrested and interned in the camps at Beaune-la-Rolande and Pithiviers, in the Loiret department of France.

Nico, his mother, sisters, wife and two children were all French citizens, so were not summoned.

The “Green Ticket roundup”. Source: Cercle d’étude de la déportation de la Shoah (Study Circle on Deportation and the Shoah)

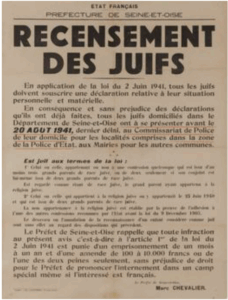

In June 1941, a second decree on the status of the Jews excluded them from mainstream society. They were forbidden from using public benches, cinemas, theaters, swimming pools, parks and public spaces.

They were also required to take part in a census, which involved going to the local prefecture to register themselves as Jews and give their personal details.

Notice about the census of the Jews in the occupied zone. Source: Museum of Jewish Art and History

This enabled the authorities to keep track of them and target them for arrest and deportation.

The census had tragic consequences: thousands of Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps and very few of them survived.

Again, we do not know if Nico took part in the census. If he did not, his identity card should not have been stamped with the word “Jew”.

We wonder if, on July 14, (the French national holiday, often known in English as Bastille Day) Nico’s sisters went to march along the Champs-Élysées in Paris, one dressed in blue, one in white and the other in red.

We can well imagine how worried Nico must have been worried about his mother and sisters, who had to endure such hardship and harassment during the occupation.

In 1942, the Vichy regime, in collaboration with the Nazis, made it compulsory for Jews over the age of 6 to wear the yellow star.

The yellow star. Source: Museum of Jewish Art and History.

This was intended to stigmatize Jews and exclude them from French society. The stars, which they had to pay for and collect from the town hall, had to be sewn onto the left breast of their clothes.

The requirement to wear the Jewish star had dramatic repercussions. It not only exposed Jews to physical abuse and harassment, but also facilitated their arrest and deportation to the death camps. They lived in constant fear. Some went into hiding to escape the persecution.

According to one of his sons, Nico did not wear the yellow star. It was not compulsory in the free zone and was not introduced even when the Germans took over the area. He does however think that his grandmother and aunts all wore the star.

Nico was therefore able to live a “fairly normal” life in the free zone until November 1942, when the Germans crossed the demarcation line.

From then on, the family, extremely worried about being caught by the Gestapo, began to look for ways to survive. Sometimes they went into hiding with friends, or sent their two children to stay with friends. Faced with this unceasing anxiety, Nico resolved to move his family to the relative safety of the free zone. They decided on a little village called Nâves-Parmelan, near Annecy, in the Haute-Savoie department of France.

View of Nâves-Parmelan. Source: Haute-Savoie departmental archives

The town hall square, where residents were assembled during the militia roundup on April 7, 1944. Source: Haute-Savoie departmental archives.

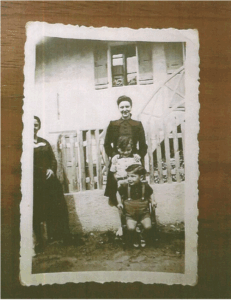

Nico rented a rustic but cosy little house there and then went back to work in Avignon. He left his wife, his mother-in-law and the two children to enjoy the crisp mountain air.

Nico’s wife Simone and their two children, Claude and Gérard, with her mother, Lucie Dreyfus, on the left. Source: Family archives.

During their time in Nâves-Parmelan, Joseph Eminet, the mayor, the school principal and the local community were very supportive of the Dassas family. Simone traded clothes with the farmers in return for eggs, butter and ham.

Nico worked for a man by the name of Roger Bellon, who owned a number of laboratories (the firm was called Orga at the time, according to a memo Nico wrote after the war). In March 1944, Mr. Bellon sent him to work for a Paris-based subsidiary “as a secretary for the Gubler company at the La Villette slaughterhouse”. Gubler made innovative products using glands and offal collected from slaughterhouses, in particular the La Villette abattoir in Paris. They were then sent to laboratories to manufacture “opotherapeutic extracts used to treat various medical conditions”.

Mr. Bellon provided Nico with a small room opposite the La Villette slaughterhouse. “A room in which I lived as inconspicuously as possible”, wrote Nico, who thus stayed away from central Paris, where there were numerous checkpoints. Nevertheless occasionally went into the city to visit his mother and sisters.

On April 7, 1944, an incident that had nothing to do with the Dassas family took place in Nâves-Parmelan. The French militia carried out a roundup there. But first, we need to explain the reasons behind this operation.

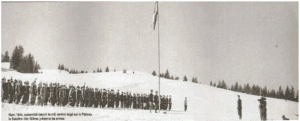

In the fall of 1943, the French Resistance asked for weapons to be sent from London. 2,500 Resistance fighters in Haute-Savoie were prepared for action. The Plateau des Glières (some 9 miles from Nâves-Parmelan) was the place chosen for the parachute drop.

Source: Nâves-Parmelan exhibition poster

After having issued a number ultimatums to the French police ordering them to curb the local maquis (resistance unit), the German army decided to take matters into its own hands. On March 26, 1944, Captain Anjot, the commander of the Glières maquis ordered the group to disperse, so when the Germans arrived, they found no one. However, as Nâves-Parmelan was not far away and on a strategically important road, the Germans set up a lookout post at the village cemetery, from which they shot six Resistance fighters. The German army then left the village. But then, on April 7, the French militia took over the village and ordered everyone to go to the town hall with their identity documents. They arrested nine people for keeping weapons in their homes, carrying forged identity papers or because they were Jewish.

We can therefore surmise that Simone, her mother and the two children went into hiding to evade the roundup. Did she tell her husband? Or perhaps she decided not to worry him further?

Nico went to see his wife and children in the spring of 1944. He then had to go back to Paris for what he knew would be a long assignment. The couple parted company on the platform at Annecy station, unaware that this would be the last time they would see each other until May 1945, almost a year later.

III) ARREST AND DEPORTATION

A) The arrest

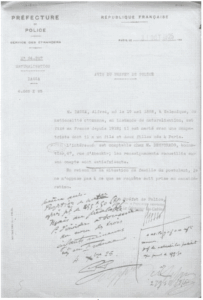

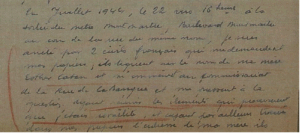

Nico Nathan Dassas was arrested at around 4pm on July 22, 1944, just as he was leaving the subway at the corner of “boulevard Montmartre and the street of the same name”.

Source: Plan of the Paris subway, showing the location of the arrest

We can safely assume that he was not wearing a yellow star, given the police officers’ reaction. According to a letter he wrote after the war, they asked him for his identity card and when they saw his mother’s name was Esther Cohen, they “twigged”. They initially took him to the police station on rue de la Banque, where they beat him.

General Commission for Jewish Affairs. Source: Licra, March 25, 2022

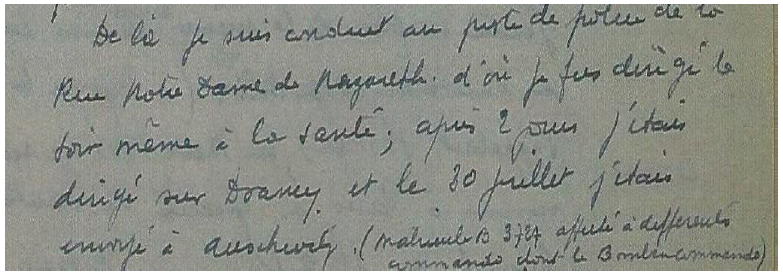

Part of the letter that Nico wrote after the war

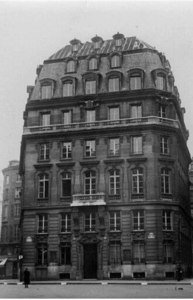

The police station on rue de la Banque. Source: Wikipedia.

The police gathered various documents to prove that Nico Dassas was Jewish and in doing so, found his mother’s address. Nico was then taken to his mother and little sister Odette’s apartment.

Nico’s mothers apartment at 35 boulevard Saint-Martin (3rd floor)

When they arrived outside the building, Nico had the presence of mind to shout out to the concierge that he was under arrest. She reacted immediately and ran to warn Esther and Odette, who had just enough time to escape down a different staircase from the one the French detectives and Nico were going up.

His mother, when she saw from a window that her son was walking out of the building onto Boulevard Saint-Martin, flanked by two policemen, said to her daughter Odette: “If he turns around, he’ll come back”. He did indeed turn around and come back! It has since become a family tradition for the grandchildren to turn around and come back when they leave their grandparents’ home.

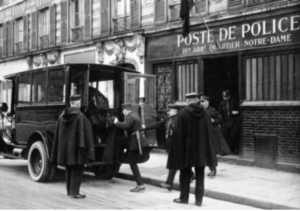

Nico was then taken to the police station on rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth, and from there to the La Santé prison. Two days later, he was transferred to Drancy internment camp.

The police station on rue Notre Dame de Nazareth. Source Wikipedia

The La Santé prison. Source : Open Edition Journal

Drancy from the air. Source: Holocaust Encyclopédia

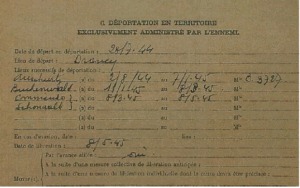

Source: Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War

B) Internment in Drancy

Source : Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War

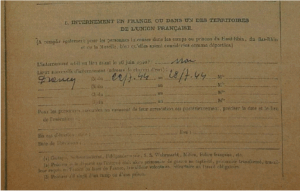

Nico was offically arrested and transferred to Drancy camp on July 22, 1944.

The courtyard at Drancy,

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, multimedia encyclopedia

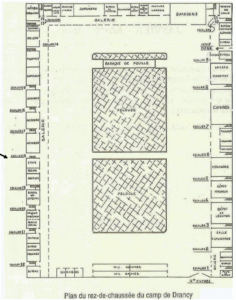

Drancy camp was in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department of France.

Aloïs Brunner, who had been in charge of the camp since June 18, 1943, was an Austrian SS officer whose sole objective, from the moment he arrived, was to hunt down all the Jews in France. He increased both the number of roundups and the degree of abuse within the camp.

Photo of Aloïs Brunner, Source: France info (AFP archives)

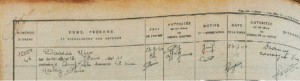

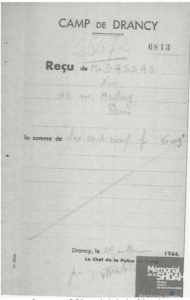

When Nico arrived in Drancy, he was carrying a small sum of money (609 francs), which was immediately confiscated. In fact, a search hut had been installed in Drancy camp, and the internees had to deposit all their money and valuables there. The 173 search logbooks from Drancy, which contain duplicates of some 18,000 receipts, are now kept at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

Nico’s receipt from Drancy camp. Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

After having handed over the money, Nico was assigned the serial number 25,672 and sent to a room on the 4th floor on staircase 18.

Source : Shoah Memorial, Drancy

The living conditions at Drancy were far from easy. People slept crammed together on the concrete floor. The buildings had no heating or basic amenities. The showers were in a barrack hut at the far end of the courtyard.

The living conditions at Drancy were far from easy. People slept crammed together on the concrete floor. The buildings had no heating or basic amenities. The showers were in a barrack hut at the far end of the courtyard.

Diphtheria (a respiratory infection that can damage the central nervous system, throat and other organs, leading to death by asphyxia/sickness, in short) spread through the camp like wildfire due to overcrowding.

We can only imagine how distraught Nico must have felt, and how worried he must have been about his mother being left alone and having no idea what was happening to his wife and children.

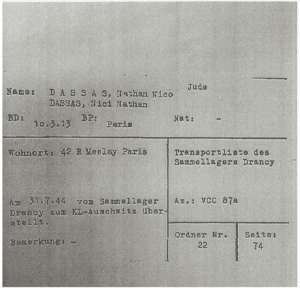

Drancy to Auschwitz transport card.

Source: Yad Vashem

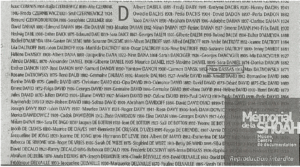

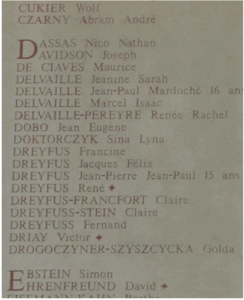

Nico Dassas left Drancy on July 31, 1944 on a transport that later became known as “Convoy 77”.

C) Deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau

After he was arrested in Paris, Nico was deported from Drancy aboard Convoy 77, bound for Auschwitz.

Source : Convoi 77.org

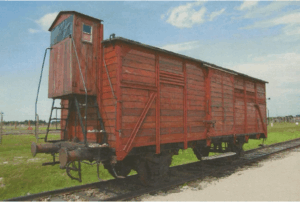

Along with many other people, Nico climbed aboard a freight train. 1306 Jews were deported on this convoy, including 324 children under the age of 16 and 986 men and women.

The transportation conditions were horrific. The deportees were all crammed together in cattle cars, with a tin bucket for a toilet. According to several eyewitness accounts, the journey itself began to sort the prisoners before they even arrived in the camp. Some died of thirst, hunger or because they driven mad. As Nico recounted during an interview on July 3, 1945, “on the way, the car I was in was only opened twice, once to empty the bucket and once to fetch water”.

A cattle car in which people were deported to the camps.

Source: 447 Holocaust Train, photo and image bank

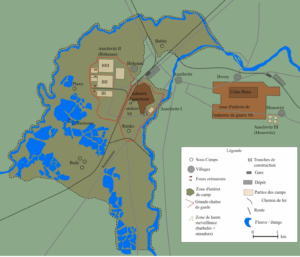

The Auschwitz-Birkenau camp was in Poland and covered an area of around 430 acres (175 hectares). It was both a concentration camp and an extermination center.

Plan of Auschwitz in 1944. Source: Memoirevive.org

Source : Unesco

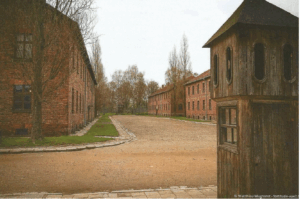

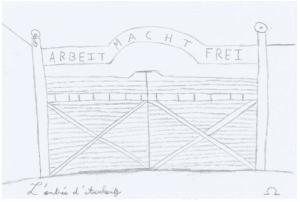

The entrance to Auschwitz. “Arbeit macht frei”, loosely translated, means “Work sets you free”.

Source : Drawing by Edwin Castel

Source : www.gettyimages.fr

The train arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau at 3 a.m. on the night of August 3 to 4, 1944. As Nico later recalled: “We immediately got out of the cars, leaving behind all our belongings. We were then made to stand in line, one by one. Once the line was complete, we marched in front of an SS officer, who waved the prisoners either to the right or to the left. On the right were women, children and the seniors, along with anyone whose physical appearance appeared to be too weak.”

Nico was sent to the left, which meant that he had been selected to enter the camp to work. He then had to walk to the Birkenau camp. “We passed through various offices where everything we had was taken from us, leaving us with only our belts and shoes. We were then taken out naked into the courtyard and into the showers, where we were shorn and shaved. After the shower, we changed into our prison uniforms. Then we were taken to the quarantine block to be interrogated and tattooed.”

Nico was then assigned a serial number: B-3727. He had to learn it in several languages and be able to say it out loud immediately in order to avoid being beaten or bullied. From that moment on, he no longer had a name. The number became his identity: yet another humiliation inflicted on him by the Nazis.

Serial number B-3727

He was then assigned to the block where he was to sleep. The barrack hut was lined with wooden bunks on three levels, with thin straw mattresses and old, threadbare blankets.

The inside of a block.

Source: Regional education department website pedagogie.ac-nantes.fr

A deportee’s uniform. Source: Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy

The Germans used a system of symbols to differentiate between types of prisoners.

The symbols used by the Nazis to identify the deportees.

Source: Memorial to the deportees from the Ain department of France, in Nantua

Nico most likely had a yellow star on his uniform. He would have been watched over by “common law prisoners” (i.e. thieves, murderers, etc.) who had green triangles on thiers. These men were mainly German or Polish.

After spending four days in the quarantine block, Nico was no doubt sent to the roll-call area with all the other deportees. He was initially assigned to work on an earthmoving site. As he explained later: “On the site, and everywhere else, every time a guard passed by, we were beaten and told we weren’t moving fast enough. We were given 250 grams [half a pound] of bread a day, a liter of soup and a slice of sausage or a little marmalade or margarine.”

The roll call area in Auschwitz,

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, multimedia encyclopedia

Three weeks later, according to the statement he gave to the Annecy gendarmerie (French military police) in July 1945, Nico and 60 other prisoners were sent to work in the Bombensucherkommando. This Kommando, which was founded in the summer of 1944, was responsible for clearing unexploded bombs from industrial sites not far from the camp, at Tschechowitz. The camp commander was SS-Oberscharführer Wilhem Edmund Claussen.

This was one of the most dangerous jobs, as none of the men had any bomb-disposal training. Nevertheless, as Nico told his sons: “It was very risky work, but it earned me a short break after every bomb I dug up”, and “I sometimes got a cigarette as a reward”. A cigarette could be used as a bargaining chip in exchange for a little extra bread, or a bit of soap, for example.

Source : Nico’s letter

In common with all the other deportees, Nico’s greatest fear was surely that of being selected to be sent to the gas chambers, and his main obsession would have been getting enough to eat.

An extra spoonful of soup could mean living another day…

Losing weight, being exhausted from work, being injured, or running a fever: all these could lead to being selected for the gas chambers. Fortunately for Nico, however, he had two major advantages: he was young, at only 31, and he no doubt had his heart set on seeing his wife, his two little boys, his mother and his sisters again.

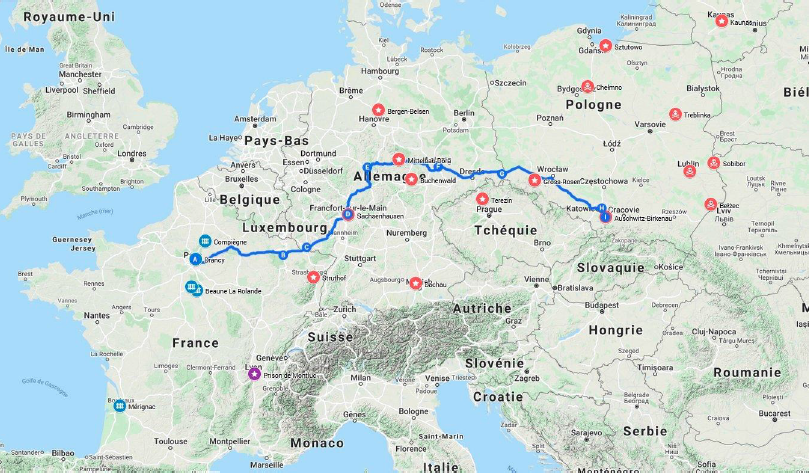

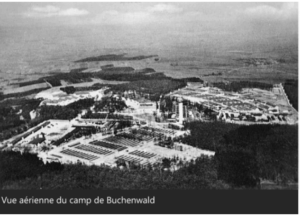

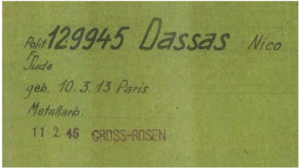

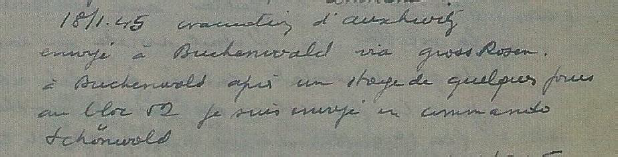

After spending 6 months in the Auschwitz camp, followed by a short stay in Gross Rosen, Nico Dassas was transferred to the Buchenwald camp.

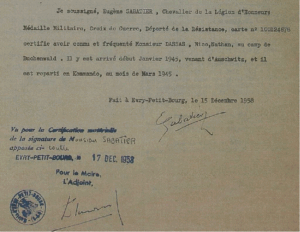

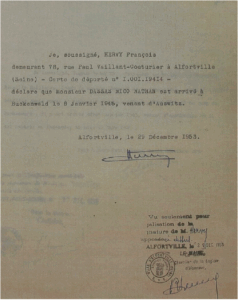

According to Nico, he left Auschwitz on January 18, 1945. However, François Hervy testified on December 29, 1953 that he arrived there on January 8. Eugène Sabatier, meanwhile, wrote in December 1958 “I certify that I met and spent time with Mr Nico Nathan Dassas in the Buchenwald camp. He arrived from Auschwitz in early January 1945 and left with a Kommando in March 1945”.

According to historical records, between January 17 and January 21, 1945, more than 50,000 deportees were forced to march to other camps in extremely harsh conditions (freezing temperatures, no food or water, shot on the spot if they could no longer move forward, etc.). These forced evacuations later became known as the “death marches”.

Other prisoners were evacuated in open railcars, also exposed to freezing temperatures.

Nico experienced both of these scenarios. In his interview with the French military police, he said: “We set off in a line during a blizzard and marched 120 kilometers (75 miles) with only one five-hour rest stop. We were guarded by the SS, and it was impossible to stop even for a moment. Fellow prisoners who could no longer walk were killed mercilessly.”

After that, Nico was loaded into an open railcar. 36 hours later, he arrived at at Gross Rosen, where he stayed for 17 days, crammed into a barracks along with 1,600 other men, even though they were only designed for 250. Food rations were even smaller there too.

D) Nico’s time in Buchenwald

Source: History-geography textbook, Belin, 2016

The Buchenwald camp. Source: Memorial to the deportees from the Ain department of France, in Nantua

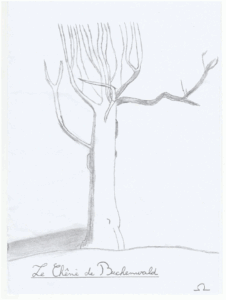

Drawing of the oak tree in Buchenwald, by Edwin Castel

Nico arrived in Buchenwald on a train from Gross-Rosen on February 10 or 11, 1945.

As we said earlier, large numbers of deportees were transferred for a second time in open cattle cars, and many died as a result of the extreme cold.

Source: Arolsen archives

Buchenwald was a Nazi concentration camp, meaning that it was a forced-labor camp rather than a killing center. Although the living conditions were still appalling, and many prisoners died of exhaustion or ill-treatment, Nico Dassas no longer had to live in fear of being selected for the gas chambers.

in July 1937 on a hill in Ettersberg, near Weimar, in Germany. Initially intended to hold opponents of the Third Reich, most of whom were communists or social democrats, it was subsequently used to hold 10,000 Jews arrested during Kristallnacht in 1938, as well as gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, political opponents and prisoners convicted of common law crimes.

During the Second World War some prisoners of war were also held there. Later on, deportees arrived from other camps, in particular Auschwitz and Gross Rosen. By February 1945, the number of prisoners had risen to 120,000, despite the fact that the camp had only been intended to hold 16,000. (Source: Wikipedia)

When prisoners arrived at the camp, it must have been much the same as it had been at Auschwitz, with the SS shouting orders and dogs barking.

If we draw on the testimony of Armand Giraud, a member of the Resistance in the Vendée department, we can visualize Nico’s arrival at the camp:

“In the distance, we made out the barbed wire fences. Further on, we spotted the wooden barracks: this was the camp we were heading for. There was a large wrought-iron gate with huge gold letters above it: “Jedem das Seine”, meaning “To each what he deserves”. Rightly or wrongly, this place was to be my home. All you who enter here, lose hope. It was with this dire warning that the Buchenwald camp welcomed the men who were to live and die behind the barbed wire fence.” (Source: Wikipédia)

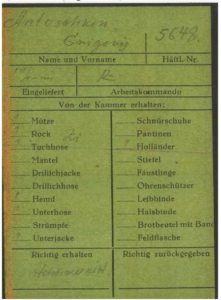

Nico arrived wearing only his deportee uniform: Rock (light jacket), Tuchhose (canvas pants), Hollander (wooden clogs), hemd (shirt), unterhose (underwear), unterjacke (vest) and mutze (hood).

Source: Arolsen archives

This time, he was assigned the serial number 129,945.

Nico’s record card, held in the Bad Arolsen Archives reveals that he was listed as a “Metalarbeiter”, meaning metal worker.

Source: Arolsen archives

We suppose that he manufactured or repaired metal parts for the Nazi war machine. At Buchenwald, deportees classified as “Metalarbeiter” assembled parts for airplane wings, for example.

The working conditions were exceptionally demanding, with over twelve-hour shifts, a maximum thirty-minute break, insufficient food and severe punishments handed out at random.

Then again, other records suggest that Nico was held in the “Kleines Lager” (small camp). On February 26, 1945, he was transferred to an outdoor camp at Berga an der Elster, where the work entailed digging underground tunnels to house the armaments factories. The work was extremely arduous. Hygiene standards were abysmal: there were no washing facilities, and food was almost non-existent. He is reported to have spent several days there, in “Block 52”.

However, in his application for deportated persons status and in his handwritten letter, Nico mentioned that he left for the “Schönwald” Kommando on March 8.

Source: Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War

Source : Nico’s handwritten letter

The Buchenwald Memorial has no knowledge of this Kommando.

By contrast, we gather from his testimony that he left the Berga an der Elster camp on April 12, 1945. He then walked more than 400 kilometers (250 miles), living on nothing but soup. The guards abandoned him on May 6, 1945.

We also know that he was not alone. He had two other deportees with him, including one known as “Little Maurice”. They were able to face up to the day-to-day suffering and humiliation as a group. Together, they were both stronger and better able to withstand the experience.

Map showing the dates on which the camps were liberated. Source: Radio France internationale

IV) LIFE AFTER THE CAMPS

A) The return journey

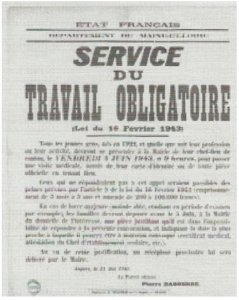

After the guards abandoned him on May 6, 1945, Nico was liberated by the Allies on May 8 and ended up in an S.T.O. (Service du Travail Obligatoire, Compulsory Work Service) camp in the Sudetenland region of what is now the Czech Republic.

Official poster on the formation of the STO.

Source: Cholet municipal archives

S.T.O stands for Service du Travail Obligatoire. This Compulsory Work Service scheme was introduced in 1943 by the Vichy regime, in response to pressure from the Nazis. It required young French people to go and work in Germany to support the Third Reich’s war effort. In 1943, Germany was short of manpower. It needed men to work on farms, in factories and in the mines.

Nico wrote that he spent ten days in “the Erlingen hospital”. He then began to make his way back to Nâves Parmelan. On May 26, he was in Falkenau an der Eger.

Source : Auschwitz Memorial

Falkenau, a former municipality in Saxony, was liberated in May 1945 by the U.S. Army’s First Infantry Division: the Big Red One. Samuel Fuller, one of the soldiers who later became a well-known film director, filmed the liberation. Some of the images can be found in Falkenau, vision de l’impossible, Samuel Fuller témoigne (Falkenau, vision of the impossible,Samuel Fuller testifies), by Emil Weiss.

That same day, Nico was sent to Bamberg, a town in the metropolitan region of Nuremberg in southern Germany.

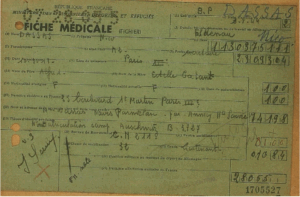

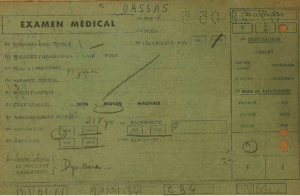

On May 28, he arrived at the Longuyon repatriation center in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France. Based in the former Lamy barracks, this center opened in May 1945, when the concentration camps began to be liberated. It was a transit point where repatriated deportees were given medical examinations to determine their state of health. They had to complete various formalities to establish who they were and where they had come from, and they were also given a range of practical assistance, food, clothing and temporary accommodation. However, according to the testimony of Yvette Lévy, who was also deported on Convoy 77 and returned via Longuyon, the Red Cross staff were not very welcoming. The deportees were simply disinfected with DTT (a popular insecticide at the time) and given a square of chocolate, after which they were put back on a train, without so much as a blanket, and sent to Paris or elsewhere in France.

Nico’s medical card states that he had lost around 45 pounds (his wife said it was around 66) and was suffering from eczema and diarrhoea.

Source : Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees, French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy

On May 30, 1945, 24 days after the Nazi guards had abandoned him, Nico arrived in Paris, thrilled to be reunited with his family. He had to start rebuilding his life and recover his strength. Like many of his fellow deportees, Nico was very modest, and spoke very little about his experiences in the camps. He did not want to frighten his children. Little by little, he returned to normal life.

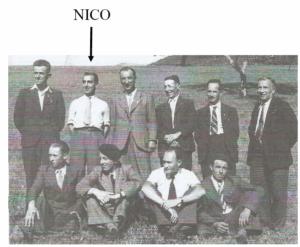

In late August 1945, a celebration was held in Nâves-Parmelan to mark the return of the prisoners. In the following photo, Nico is pictured with a group of other men who were arrested for their involvement in the Resistance.

Photo of the men arrested in Nâves-Parmelan.

Source: Le Dauphiné Libéré, August 1945.

B) Nico’s return to family life and to work

When Nico got back to Paris, the family set up home on rue de Trévise in the 9th district, and then moved to rue Galilée in the 16th district. The family grew larger with the birth of two more boys: Alain and Thierry.

Although Nico’s mother observed the fast on Yom Kippur, the children were not raised in a religious environment.

Nico went back to work to support his family. He caught up with Roger Bellon, who gave him a job, and he rose up the ranks in the laboratory. He became the export manager, then the sales manager, and ended his career as the managing director.

The firm soon made a name for itself with the development of antibiotics, which were in great demand after the war. Nico travelled abroad extensively, particularly to the USA and Latin America.

He demanded only the highest educational standards from his children: he would often say “be the best of the best”. He felt it important for them to have an international outlook. They therefore had to speak English fluently, and were expected to study at prestigious American universities such as Harvard.

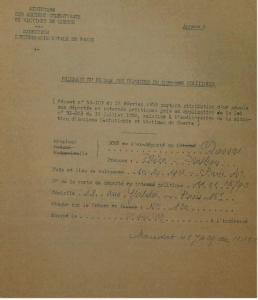

Nico Dassas applied for the status of “political deportee” on January 8, 1960.

Source : Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War, French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy

However, in order to be officially recognized as a political deportee, applicants had to submit proof that they had been deported, including witness statements.

Nico’s application included two witness statements.

The first was from Eugène Sabatier, who was born on June 21, 1918. He was deported on a convoy from Compiègne to Buchenwald on May 14, 1944. His serial number in Buchenwald was 51228.

He was placed in a large tent in the “Petit camp” (small camp) section of the camp. As of June 7, 1944, Eugène Sabatier worked in the Gustloff II arms factory, near the camp. After he returned to France, he was made a Knight of the French Legion of Honor, and awarded the Military Medal, the French Croix de Guerre and the status of Deported Resistance Fighter.

The other testimony that Nico submitted was from Hervy Francois. He testified on December 29, 1953 that Nico Dassas had arrived in Buchenwald from Auschwitz on January 8, 1945. His serial number in Buchenwald was 81507.

Whether these two men worked with Nico Dassas in any Kommando in particular, we do not know.

In December 1960, Nico Dassas was officially granted the status of political deportee and issued a card bearing the number 110126799.

Source : Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War, French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy

In 1971, he was awared the French Legion of Honor for military service.

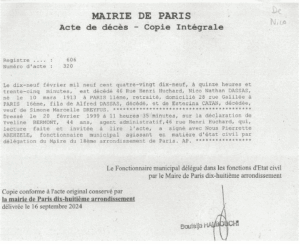

Nico’s wife, Simone Marcelle Dassas, passed away on December 24, 1982, in Boulogne-Billancourt, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of France.

Source : Paris city archives

Nico Dassas died at the age of 85 a 3:35pm on February 19, 1999 à 15h35 at the Bichat hospital in the 18th district of Paris.

Both he and his wife are buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Nico’s death certificate. Source : Paris City Hall

Source : Nico Dassas’ tomb at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris

Nico was unable to attend the inauguration of the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, which pays tribute to the 76,000 Jews deported from France. However, his children and grandchildren can still visit the site and see his name engraved in stone.

Nico Dassas’ name inscribed on the Wall of Names. Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

There is a also a memorial in Avignon, in the Vaucluse department of France, dedicated to the Jews from the department who were “deported to Nazi extermination camps between 1942 and 1944”.

The plaque was unveiled on April 23, 2010. Among the many names listed on it is that of Nico Nathan Dassas. The plaque is at 2, montée des Moulins in the Jardin des Doms, also known as the Rocher des Doms.

The memorial plaque in Avignon. Source: Geneanet

Nowadays, their children and grandchildren recall with fondness and respect all the happy and unhappy times that Nico and his wife Simone experienced, thus keeping the memory of them alive. The passing on of these memories to the great-grandchildren is an essential task, and is already in progress.

Nico Dassas surrounded by his wife, his children and his grandchildren

TRIBUTE

The students from the Convoy 77 workshop were keen to pay tribute to Mr Nico Nathan Dassas, to ensure that no one will ever forget this dark period in history. They were particularly impressed by his ability to move on with his life, from both a personal and professional perspective, after such a traumatic experience.

THANKS

The class would like to thank Mr. Alain Dassas, one of Nico’s sons, without whom this project would have never been as comprehensive as it is today. He was always available and supportive of our work.

Ms. Varin would also like to underline how lucky she was to work with Mr. Dassas, for his kindness and attention to the project, and for the trust he showed in her by allowing her to delve into his family history.

We would also like to thank Maggy Bonnemains for producing the exhibition poster, and Edwin Castel for his drawings.

STUDENTS’ COMMENTS ON THE CONVOY 77 PROJECT

Mélissa: “I really enjoyed studying the life of a deportee, his family, his wife and his children who were kept hidden. However, there were times when I was unable to find anything new, so could not move on.”

Faustine: “I very much enjoyed taking part in this project because it was great to work as part of a team. I also enjoyed talking to Nico Dassas’ son. However, there were a few frustrating moments, such as when we were unable to find all the information we wanted. The Convoy 77 project took me out of my comfort zone, as I had to make phone calls and had to be patient.”

Evan: “I felt there was a good atmosphere in the class, even though it was a serious subject. I discovered a lot about Jewish history as well as the Second World War.”

Mathilde: “I had a very good year. I enjoyed carrying out the research even if it led nowhere at times. It taught me how to work as part of a team, to remain patient and to be thorough. The atmosphere in class was great. I have no regrets about joining the program. We were very lucky to work with one of Mr. Dassas’ sons.”

Julie: “I found the project very interesting. When you study what happened to a Jewish person, you can’t help but imagine how they might have felt and what they might have gone through in their everyday lives. I feel it is important never to forget such historical events in the light of the current resurgence of anti-Semitism. It sometimes took us a long time to find information, but when we did, we were thrilled. The year went well and I emerged from it better informed.”

Jade: “The Convoy 77 project is a truly fantastic experience. Working on the life of a deportee gave me a way of paying tribute to him, in a way. At the beginning, we did some research without even knowing if we were going in the right direction, and when we began to find things out, I was so pleased. It was very satisfying. When Ms. Varin told us that Nico Dassas’ son had contacted her, I was really thrilled. If I had to do it again, I would not hesitate for a second: it’s a fantastic opportunity. I really enjoyed those Thursdays from 10 to 11 am. It’s such a shame it will all be over soon!!”

Raphaël: “I’ve learned a lot from the Convoy 77 project. I’d definitely encourage anyone interested in the Second World War, the lives of Jews in France during the war, or deportation to take part in it.”

SOURCES

- French National archives

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. File on Nico Dassas, ref. 21 P 629 122

- Shoah Memorial, Paris

- Archives from Yad Vashem in Jérusalem (Déborah Meyer)

- Arolsen archives – International Tracing Service

- Rhône-Alpes departmental archives

- Haute-Savoie departmental archives

- Shoah Memorial, Drancy

- The Auschwitz Memorial

- Mémorial de Buchenwald

- French Union of Auschwitz deportees

- French Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation

- Flossenbürg nonprofit organization

- Nâves-Parmelan town hall

- Our discussions with Nico Dassas’ son: Alain Dassas.

- Our discussions with the Convoy 77 team: Claire Podetti.

- Our discussions with a resident of Nâves-Parmelan: André Rezvoy

Historical documentation found in April after extensive research by the students

Source : Rhône-Alpes departmental archives (photocopy of the original document)

Source : Rhône departmental archives (translated by Mr. André Rezvoy, who lives in Nâves-Parmelan)

Français

Français Polski

Polski