Nicole Cario

“The distinction between our family histories and what we call History, with its pompous capital letter, makes no sense. They are exactly the same thing. There is not, on one side, the great and good of this world, with their scepters and televised speeches, and on the other side, the drudgery of daily life, the short-lived anger and hope, the anonymous tears and unknown people whose names are rusting away at the foot of a war memorial or in some country cemetery.” Ivan Jablonka, in “A History of the Grandparents I never had”.

To begin with, the students worked on this passage and thought about the ways in which family stories shape History, because I had been so impressed by the book. I had no idea that the Jablonka family knew one of Régine Balloul’s daughters, a sister of Esther Cario, Albert Cario’s wife. We only discovered this at the end of the project.

What follows is the students’ work, in their own words.

Photograph of Nicole kindly provided by a cousin, one of Régine Balloul’s daughters

In order to read the documents in the biography more clearly, click on the images to see them in their original format

A girl who lived in our neighborhood

This little girl was called Nicole Fanny Cario and she was born on June 24, 1936 in the 14th district of Paris. Her parents were Albert Cario and Esther Balloul.

She was born during the period that the Front Populaire (Popular Front) was in power. She lived in the 20th district of Paris, a working class neighborhood where there were many immigrants, including the Cario family, who lived at 54 rue Pelleport.

A map showing where Nicole lived, at 54 rue Pelleport, her school, at 103 avenue Gambetta, and our school, on rue des Prairies.

There is still a school at 103 avenue Gambetta, just a stone’s throw away from our college, as shown on the map.

A photograph of Nicole from the book written by the Tlemcen School Committee. The original photo came from Serge Klarsfeld.

We began to wonder about a few points: Was Nicole able to benefit from her parents’ paid vacations? Was she dead or alive in 1949, the date of her birth certificate? What does the plaque at 103 avenue Gambetta, which we saw on Google maps, relate to?

When we went to look, this is what we found:

54 rue Pelleport today

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The context in which Nicole Cario was arrested and deported

The Cario family was arrested on July 20, 1944.

In 1944, France was divided in two. The free zone, in the south, was ruled by Marshal Pétain, who had been in power since 1940, and the occupied zone in the north, which had been taken over by Nazi Germany, also in 1940.

The Russian army’s victories over the German army in Europe (including Stalingrad on February 2, 1943) enabled it to conquer and/or recapture a number of areas, particularly on the Eastern front, including in Finland, Romania and Bulgaria, where the Germans retreated. Moreover, on the Western Front, the conquest of Italy (one of the three Axis countries, together with Japan and Germany) began in January 1944.

Source : United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The Eastern Front: In the summer of 1944, the Russians launched a major offensive, which liberated the remainder of Belarus and Ukraine, the Baltic states, and eastern Poland from Nazi domination. In August 1944, the Soviet troops crossed the German border.

Nazi Germany began to lose more and more battles to the USSR and on June 6, 1944, the Americans, British, Canadians and some French resistance fighters led by General de Gaulle landed in Normandy. Faced with successive military defeats, Hitler ordered the German troops to deport and kill more Jews.

This was the context in which Convoy 77, one of the last large convoys from France, was organized. It left Drancy for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, carrying more than a thousand Jews.

The German troops in France became even more focused on their task, aware that there were only a short time left before the Allies reached Paris. This proved to be true, since Paris was liberated on August 26, 1944.

Nicole Cario was arrested and deported about a month after the Allied landings in Normandy and a month before Paris was liberated. This marked the end of the Vichy regime (which was replaced by the CFLN, the French Committee for National Liberation, which became the new government) and the last council of ministers in Vichy was held on July 12, 1944. For the German army, it was a debacle. France was liberated little by little thanks to the Allies.

Internment in Drancy camp

A cattle car at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy. The class visited the Drancy Memorial in March.

During their visit to Drancy, the students were able to listen to some testimonies of children who were interned in Drancy camp, such as Francine Christophe, Jacques Szwarcenberg, Annette Landauer and Gil Tchernia.

Francine Christophe was arrested together with her mother in 1942, when she was eight and a half years old. They were deported to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on May 7, 1944 on Convoy n°80. Jacques Szwarcenberg was deported to Bergen-Belsen in February 1944 at the age of 11. Annette Landauer was arrested during the Vel d’Hiv roundup in 1942 and imprisoned in Drancy when she was 11 years old. Gil Tchernia was arrested and imprisoned in Drancy in 1943, when he was 4 years old.

When they arrived in Drancy, the German authorities, their agents or the French police searched through their luggage, if they had any. They were then registered and those who did not already have a yellow star were made to wear one.

Communication with the outside world was allowed. People from the outside sent food packages to the deportees, which they shared among themselves in their rooms. They sent letters sewn into the hems of clothes, which were hardly visible, so that the German authorities would not notice them.

The witnesses describe the rooms as smelly, with blood-stained, disgusting mattresses on the floor. The internees were divided into 60 rooms, so there was no privacy. There were no showers, so they had to wash themselves with water from a faucet.

The testimonies of those who survived prove that they were the exception to the rule, as the vast majority of the internees were deported and died in the killing centers. It can be said that they were “lucky” to escape death, but nevertheless they lived in atrocious conditions. They were afraid, hungry, filthy, disease ridden and often subjected to violence. These witnesses now remember Drancy camp as a place where they suffered enormously. It is an experience that they never want to forget, a part of their personality and their moral values are influenced by the time they spent in Drancy. Seeing it again helps them to rebuild their lives, and although they would have preferred it to become a museum, some of them believe that the fact that the Drancy camp has been converted into a low-cost housing project also symbolizes renewal and renaissance.

Students’ impressions

“One story particularly struck me: the one in which one of the former internees recalled that when he was playing on a balcony with some other children, a German soldier shouted loudly and pointed his gun at them. This episode attests to the brutality of life in the camp and the cruelty of the guards.”

“The children were treated the same as the adults. The majority of the guards had no mercy toward them and even went as far as hitting them.”

“Another thing that made an impression on me were the drawings made by the internees: dark, sad and gloomy, they depict life in the camp. This bleak and dismal way of depicting what they saw shows their despair at being interned in the camp, as shown by the titles of these drawings, “Living like a dog” and “On the threshold of hell” in particular.”

“I also saw the remains of a wall on which is engraved a name, the date of arrival and deportation and a phrase that moved me immensely, which is “I will be back”.”

Fernand Bloch, Max Lévy and Eliane Haas were deported on Convoy 77

“What moved me the most was the story of the tunnel built by the internees to escape and then discovered by the guards. Luckily, the 12 internees who were caught were sent to another camp. On the train, they managed to escape along with the other people in the car.”

https://www.fondationshoah.org/memoire/les-evades-de-drancy-de-nicolas-levy-beff

“The hunger and the incessant noise seemed to come up again and again in the testimonies; it must have been really traumatic for them. The sanitary conditions were appalling and I can’t understand how people enjoyed making other people suffer like that. One thing that came up a lot in the testimonies, even though the camp survivors who were interviewed were not asked about it, was the fact that they did not want to be noticed because of the risk of being hurt. The example given of how important it was to respect this unwritten rule is quite simply horrifying and chilling: turning a gun on children because they were playing noisily is appalling.”

“One thing that really amazed me was that people (police officers and their families) voluntarily agreed to live in the towers overlooking the camp and thus were able to watch men, women and children suffering all day long. These people were despicable.”

“What impressed me the most during our visit to Drancy was the railroad car. This SNCF wagon was used to deport Jews to Auschwitz to be slaughtered like cattle.”

“What struck me during the visit to the Drancy Memorial and listening to the testimonies was the lack of hygiene. Knowing that people slept on the floor on mats full of excrement and that they could not wash themselves at the taps with even a little privacy shocked me. Also what struck me during this visit and listening to testimonies was the how hungry these people were in the camps. Parents would sacrifice themselves so that their children could eat and not go hungry by giving them their own food. The little boys rummaging through the garbage looking for leftovers and eating whatever they could really made my heart ache. No one deserves to be that hungry and everyone should have enough to eat. Life in the camps was monstrous for everyone and I think even more so for those who were there without their parents.”

“The fact of seeing the enormous number of children who were interned really struck me; it seemed unthinkable and senseless to me to see so many children living in such conditions, most of them without their mothers and for reasons that were completely incomprehensible at their age. No one deserves to live in such poor living and sanitary conditions no matter who they are, regardless of their background, religion or sexual orientation. These children deserved nothing of what they went through.”

“During the visit to the Drancy Memorial, the thing that struck me most was the children who must have been left with no points of reference, no parents and no brothers and sisters. And when, during their testimony, one of them said that because their soup was not enough for them, they waited for the cooks to take out the garbage so that they could eat whatever they could find. Because they were very hungry, and that made me react immediately because I find it sad that a child could not eat as much as he or she wanted.”

Her arrest and deportation

Nicole Cario was arrested and taken to Drancy camp on July 20, 1944 and then deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. She never returned from the camp, and is presumed to have died there. Her death certificate bears the stamp “died during deportation”.

She was one of the last people to be deported prior to the liberation of Paris. The convoy was filled to capacity with more than 1000 people.

In Nicole’s disappeared persons file, N° 68,644, the file numbers of her parents, Albert and Esther, both of whom also went missing, are included: 68,642 for Albert and 68,643 for Esther.

Nicole’s Drancy card is marked with a “B” which means that she was deported as a priority.

According to the Tlemcen school association, 12 children were deported from the school and there is now a plaque on the wall in memory of them.

The following image from the alphabetical list of Jewish children arrested and deported from the 20th district of Paris, taken from Serge Klarsfeld’s “Mémorial des enfants juifs déportés de France” (Memorial of the Jewish children deported from France), published by the association “Les fils et filles des Déportés Juifs de France” (The sons and daughters of the deported Jews of France). Members of the Tlemcen school association found out which schools these children went to, in order to commemorate all of the children from the 20th district who were deported and died simply because they were born Jewish:

On the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris we were able to see Nicole’s name together with those of her parents, Albert and Esther:

Research undertaken by relatives; the students investigate

Based on the records, we note that relatives of the victims, in this case Régine Vinerbet, applied for a certificate for a “non-returned person”. In the section “for relatives, note below your relationship with the “non-returned person””, she stated that Nicole was her sister’s child.

Based on the Cario family records, we can see that Régine Vinerbet, Albert Cario’s sister-in-law, filed an application to the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War on March 15, 1950, in order to have Nicole, Albert and Esther Cario’s recognized as non-returnees.

Their closest family members, such as Régine Vinerbet, were concerned about them and made inquiries to find out what had happened to them. To do this, she made a “non-returned person” declaration by submitting the necessary paperwork to the Saint Fargeau Police Department in Paris.

From the records that we have , it is impossible to tell if her request was granted. It is clear that they died, but Régine wanted to know where and in what circumstances. We noticed, however, that she had the same address as the Cario family (54 rue Pelleport, postcode 75020), so might she have lived with them?

According to the testimony sheets recorded and made available by the French committee of Yad Vashem, it was a Janine Solesco who undertook to have the Cario family listed as Holocaust victims.

This person was living at 14 rue Favart in the 2nd district of Paris.

Perhaps we could contact her by mail, we thought, and perhaps she might have some other records or information. A branch of Esther’s or Albert’s family lived in the 2nd district of Paris: perhaps they still do?

The date of birth of Esther, whom everyone called Ines, was in 1906 but on the card Janine Solesco entered it as 1912.

https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr&advancedSearch=true&sln_value=Solesco&sln_type=synonyms&sfn_value=Janine&sfn_type=synonyms

The address she gave as hers on December 17, 1991, which was 14 rue Favart, postcode 75002, now seems to be that of a restaurant called Les Noces de Jeannette, formerly the Poccardi.

The Poccardi restaurant on rue Favart

At the Bibliothèque historique des postes et télécommunications (Historical Library of Post and Telecommunications) on rue Pelleport, a search of the microfilms of old directories revealed that Janine Solesco had lived in the 12th district. However, when we went to the address given, no one was able to give us her current address.

Microfilms at the Historical Library of Post and Telecommunications

On the page on the Shoah Memorial website we noticed that at the bottom it says Coll. Laurence Cohen-Carraud. We therefore searched for what Coll means. It apparently means collaborator, in particular if someone has helped to provide an image or document. We wondered if the photo of the Cario family belonged to Laurence Cohen-Carraud, and we then tried to find out more about her: 5.

https://www.annuairetel247.com/cohen-carraud-laurence-paris-rue-dareau

Perhaps this was the person mentioned below the photo?

We got in touch with her.

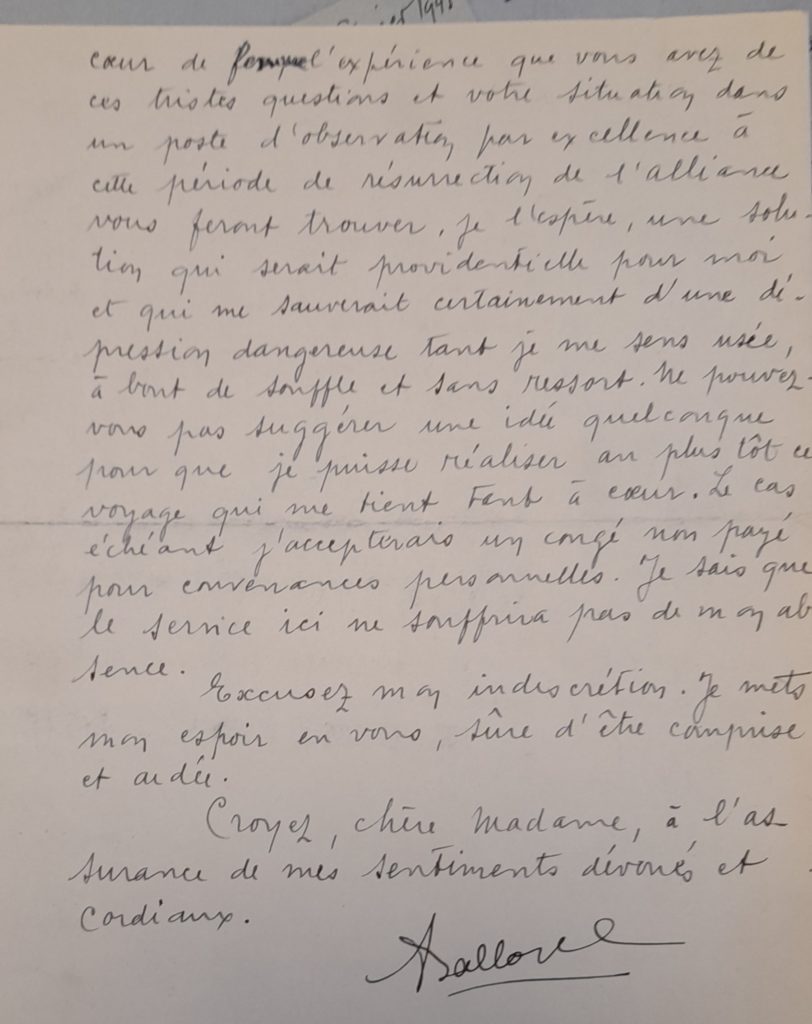

Laurence Cohen-Carraud put us on the trail of the library of the Universal Israelite Alliance schools, and in the archives, there was a letter from Amélie Balloul, Nicole’s other aunt:

Letter from Amélie Balloul dated November 28, 1944

The letter from the modern archives of the Universal Israelite Alliance (ref. AM Maroc E 019 c)

This letter was written by Amélie Balloul, another sister of Esther/Inès Cario, who was the principal of one of the 18 schools run by the Alliance Israelite Universelle (AIU) in Casablanca, in Morocco. She was writing to Suzanne Feingold, the secretary for schools at the Alliance, who joined the Resistance during the war.

Amélie Balloul had just heard that her younger sister Inès (Esther), her husband and their 8-year-old daughter had been deported to “Germany” on July 31, 1944. She must have had a very close relationship with her family because she said that her brothers and sisters were her reason for living, and her perspective, and how deeply attached she was to her family. Amélie says that she practically raised her brothers and sisters. She thought of her sisters more as her daughters because she lost her mother when she was very young, in 1927. She had contacted the Red Cross, the service for deportees, the HICEM and the president, a Mr. Tajouri, who was probably the manager of the Alliance, to ask for news of them.

Amélie is the woman who is smoking in the photo (source: The Universal Israelite Alliance library, in Paris)

Source: The Universal Israelite Alliance library, in Paris

Source: The Universal Israelite Alliance library, in Paris

In the application for French citizenship for Eliezer, one of Ines’ (Esther’s) brothers, there is some information about the family:

Also, on the French genealogy website, Filae, we found out the year in which Vidou, Ines’ (Esther) and Amélie’s mother, died: 1927.

It was through a daughter of Régine Vinerbet, née Balloul, that we discovered the story of how the Cario family was arrested: Albert and Inès wanted to stay in Paris, thinking they would be shielded by their Turkish citizenship. They sent Nicole to live with Régine Balloul in Saint-Solve in the Corrèze department for a year or so. Nicole then returned to Paris and her parents had to hide somewhere other than at 54 rue Pelleport. Nevertheless, so that she could continue to go to school, Nicole must have gone to a neighbor’s house at lunchtime.

Régine Balloul said that Nicole was most likely reported. She was arrested first, and as a result, her parents were arrested too. Nicole, Albert and Inés were all deported and gassed as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

To conclude this biography, a few final comments: “The Convoy 77 project moved us deeply because the Cario family’s story is so very sad. It enabled us to discover the cruelty that Jewish people suffered during the war. What happened to them was inhumane and we were shocked and upset by it.” “We shared in their experiences and feelings through the archived records”. “Even though Albert Cario was not born French, he volunteered in the French army and fought in it but still he and his family were deported”.

Sources :

- Archives de la Division des Archives des Victimes des Conflits Contemporains (DAVCC).

- Site de Yad Vashem

- Bibliothèque de l’Alliance

- Encyclopedia United State Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Archives de Paris

- Bibliothèque historique des postes et télécommunications

Links :

- https://www.fondationshoah.org/memoire/les-evades-de-drancy-de-nicolas-levy-beff

- https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr&advancedSearch=true&sln_value=Solesco&sln_type=synonyms&sfn_value=Janine&sfn_type=synonyms

- https://www.lesnocesdejeannette.com/restaurants-insolites-paris,

- https://www.lessoireesdeparis.com/2018/11/28/les-roses-de-poccardi/

- https://www.annuairetel247.com/cohen-carraud-laurence-paris-rue-dareau

- https://www.bibliotheque-numerique-aiu.org/tous/item/9176-photo-de-groupe-l-alliance-a-casablanca

Français

Français Polski

Polski