Rosa GOURENZEIG or Rajzla GURENCAJG, née CUKIER or TUKIER

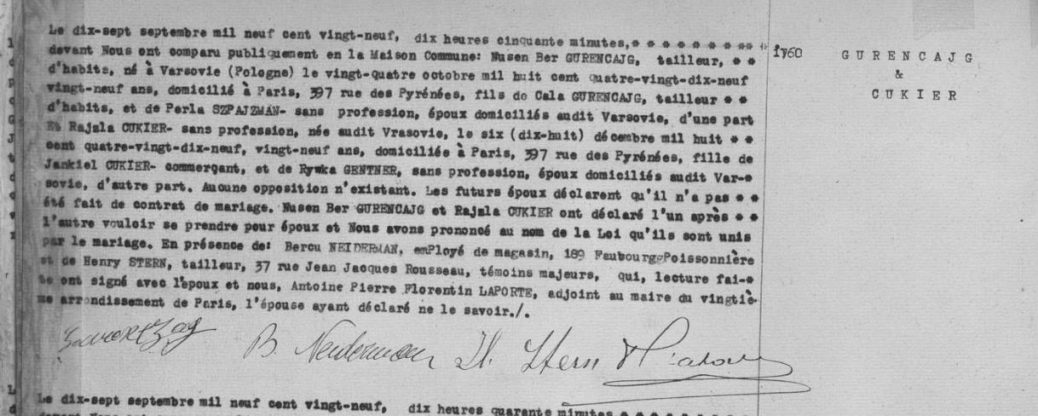

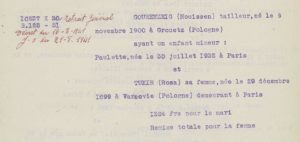

To the left, Noussen and Rosa’s marriage certificate. Source: Paris Archives, ref. 20M79

Rosa Gourenzeig, who is referred to by different names depending on the source: Tukier, Cukier, Gurencajg or Rajzla Cukier, was born in either Warsaw or Kiev, cities that were then were part of the Russian Empire.

According to her marriage certificate, she was born on December 6 or 18 ,1899 in Warsaw. She was the daughter of Jankiel Cukier, a trader, and Rywka Gentner.

It is not known exactly when she left her homeland to move to France. According to the minutes of the commercial court of the Seine department of France, Rosa must have married Nusen Ber Gurencajg, usually known as Noussen Gourenzeig, before they came to France, since it was noted that they had been “married under the Russian regime”.

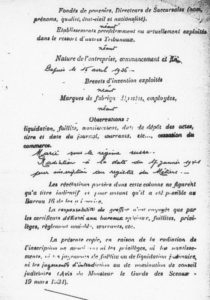

From the minutes of the commercial court of the Seine department of France

Source: French National Archives, dossier reference 662.

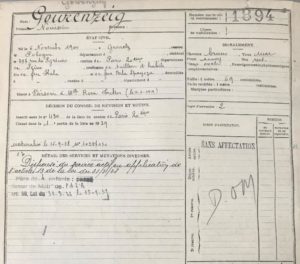

In fact, however, according to Noussen’s military service record, the marriage took place on June 4, 1919 in Warsaw, Poland.

Noussen’s military service record. Source: Paris Archives, ref. D4RI 3686

They may have needed to get married in France as well for administrative reasons, given that we know that they were married again on September 17, 1929 in Paris. Once again, from the minutes of the commercial court of the Seine department, we see that Noussen was granted permission to reside in France in 1920, and we can surmise that the same was true for Rosa.

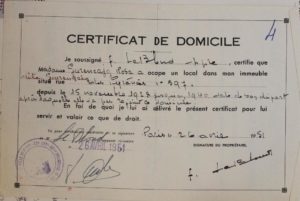

According to Joseph Fourand, her son, they set up home at 397, rue des Pyrénées, as confirmed by the 1931 Paris census and their landlord, Mr. Leblond.

Residence certificate. Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service.

In this Parisian neighborhood, where a variety of different communities lived, they had four children: André, Marie, Joseph and Paulette.

During the time she spent in Paris, Rosa Gourenzeig used to cook stuffed carp and clepors, typical dishes from her native country. Also, on Friday evenings, at the start of Shabbat, she would place a veil over her head and wept as she looked at the burning candles and thought of her family back home in Poland12. And although she often offered business advice to her husband, nowadays we would say that Rosa was a “housewife”, who took care of her home and her children. Paulette says that her mother sometimes took her to the movies, and also that her mother spoke mainly in Russian, Polish and Yiddish, but knew very little French.

In the spring of 1940, following the German offensive, Noussen sent Rosa and their children to seek shelter in a little village near Sens, where they stayed with an elderly English woman. They all returned to Paris a few days later, before the Germans moved into the capital.

Rosa, who had been granted French nationality by naturalization on September 15, 1938, according to a decree of the then President of the Republic Albert Lebrun, lost it again on August 21 1941 when the Vichy government put in place a law requiring the annulment of French citizenship accorded to Jews in particular.

Extract from the decree dated September 15, 1938 by which Rosa was granted French citizenship. Source: https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/mm/media/download/FRAN_0312_38517_L-medium.jpg

According to the article in the French newspaper Le Monde published online on December 5, 2015 “The law of July 22, 1940 provided for the systematic review of all naturalizations granted since 1927 – 1927, since the law of August 10, 1927, which replaced a very old one dating back to 1889, facilitated the acquisition of French nationality by reducing the residency requirement from ten to three years […] and by increasing the number of cases of automatic accession. Indeed, between 1917 and 1940, nearly 900,000 people acquired French nationality. […] For four years, the Commission excluded 15,154 people from the French citizenry, and lists were published in the French Official Gazette – a little fewer than half of them would have been Jews, although it is difficult to verify this. This was not a large number out of the 900,000 people who were liable to be stripped of their citizenship, because the Commission, even though the law did not mention it, was primarily aimed at the Jews. Since October 1940, Jewish foreigners had been interned in specialized camps or held in groups of foreigners, including those who had been “denaturalized”. The first deportation convoy (on March 27, 1942) changed the nature of this “denaturalization”; effectively, the wise men on the committee were now sending the Jews who had been stripped of their nationality to their deaths.”

After they lost their French citizenship, the father decided to look for a place to relocate his family in the free zone. He left first, as a pathfinder. He was arrested while trying to cross the demarcation line and spent two weeks in jail in Chalon-sur-Saône. After this initial failure, he employed a people smuggler and thus made his way to Lyon, where he found a place to live. From there, he sent another people-smuggler to pick up his wife and children. The smuggler went to Paris to pick up Rosa, but she panicked and became distraught at the idea of leaving behind the city and the memories she had of it.

The following day, she went to the Gare de Lyon station with her sons, her daughters having gone on ahead a short while earlier. However, once on the train, she was unable to find them. She decided to get off at Dijon and return to Paris to look for them. Meanwhile, her sons continued on their way with the smuggler, but they were arrested while trying to cross the demarcation line and imprisoned firstly in Chalon-sur-Saône and then in Autun.

After 8 weeks in captivity, the boys returned to Paris. Since they were wanted by the police, Rosa decided to leave Paris with her children in order to meet up with her husband and take refuge with him in the free zone. She found a people smuggler who took them to the demarcation line near Chalon-sur-Saône. They then had to cross the border on foot, in the snow. Rosa’s silk stockings stuck to her legs. When she arrived in Lyon, her husband used tweezers to remove the fragments of her stockings encrusted in her skin.

The apartment was on the fifth floor of a building at 11, place Antonin Gourju, in the 2nd district of Lyon. It was made up of two large rooms furnished with chests and a typical Lyon-style kitchen.

Rosa was happy there, surrounded by her family. Her husband’s work and income provided enough money to support everyone. However, on November 9, 1942, everything changed: this was the day on which the Germans crossed the demarcation line. Rosa wondered whether it would be safer to flee to Switzerland, but her husband refused, which caused some friction between them18. Food was difficult to come by and Rosa, who was a heavy woman, lost a lot of weight. Paulette recalls that meals often included fava beans cooked in water. Rosa was upset because she could not feed her family as well as she would have liked.

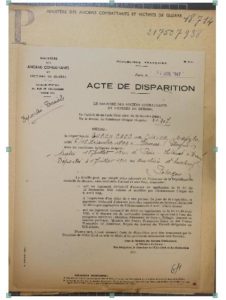

On July 18, 1944, as documented in her missing persons certificate, Rosa was arrested at her home by the French Gestapo, together with her husband, her son Joseph and her husband’s two Polish employees. They were taken to the Gestapo headquarters, which had been on Place Bellecour since May 26, 1944, when Allied shelling destroyed its former headquarters on Avenue Berthelot.

Missing person’s certificate. Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Meanwhile, André hid in a closet in their apartment and avoided being seen by the Gestapo soldiers. Rosa’s other daughter, Marie, had managed to escape and Paulette had been sent to live with a family in the country. Rosa was still a mother, however, and must have been worried about Marie, who had run off and from whom she had no news, about Paulette, who was staying with strangers in the countryside, and about André, who was a frail child and had been separated from the others.

She may have been arrested due to having been denounced in a letter from her cousin’s mother-in-law, but this was just a hypothesis put forward by Joseph and his father; it has never been substantiated.

After spending a night in the Gestapo building, Rosa was separated from her husband and son in the Montluc jail, which was at 4, Rue Jeanne Hachette.

The Jews’ barracks in the main exercise yard

Source: Rhône departmental archives, ref. 4544 W 17

The location of the Jews’ barracks today. Source: Photo by Christèle Vial

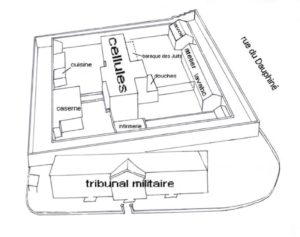

Plan of the Montluc prison

Source :http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media496-Plan-de-la-prison-de-Montluc-Lyon#fiche-tab

She stayed there for a total of 6 days, from July 19 to July 24, 1944. The men were separated from the women, and the young children were placed in hospitals. As for Rosa, she may have been held in the workshops or in the prison barracks. At first, she was alone, but a few days later her daughter Marie, who had been captured, was sent to the same jail.

In the prison, resistance fighters, civilians, opponents of the Nazi regime and Jews were all kept together and were subjected to more abuse than the other prisoners. The men, such as Rosa’s husband and son, were held in what was known as the “Jews’ barracks”. The detention facilities were horrible: the cells were very narrow, with 8 to 10 people in each. The prisoners had no proper beds, since they had been removed after someone escaped, so they only had three sacks of straw. There was one basin of water for washing and one bucket to relieve themselves, both of which the prisoners had to share. As a result, they had to endure the stench and unsanitary conditions. Their only activity was going outside for 45 minutes a day. The only food provided was a hunk of stale, black bread and a piece of tough meat. In the evenings, the Red Cross brought them a bowl of soup. Diseases were rife due to the poor living conditions, and there were lice, fleas and rats.

After her stay in Lyon, on July 24, 1944, Rosa was transferred to the Drancy transit camp.

Jews interned in Drancy camp, France, between 1941 and 1944

Photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Source: http://www.ajpn.org/images-camps/1287327403_juifs.jpg

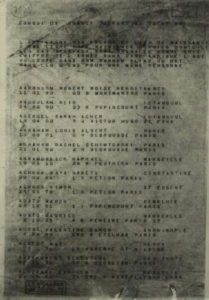

Extract from the list of people deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. Source: Copy of 1.1.9.9 / 11191135, in conformity with ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives.

Alphabetical lists of Jews deported from Drancy transit camp (Original transport lists held by the French National Research Agency)

Drancy was made up of 3 distinct sites, 3 blocks of buildings in the shape of a “U”. The section on the left was for the prisoners detained in cells, who were frequently shot. The section on the right was for people who were to be deported. The middle building was used to hold the Mischlingen, which means Aryan men or women who were married to Jews. During the day, they were free to go outside, except for the day before a deportation convoy, when a fence was erected to cordon off the building on the right.

The camp gates were guarded by French police. During the Gourenzegs’ internment in the camp, on July 28, 1944 to be precise, the courtyard was fenced off to separate the Jews from the other prisoners.

On July 31, 1944, 17 days before the camp was liberated, Rosa and her family were deported to Auschwitz Birkenau by train, on Convoy 77, (the last of transport to leave Drancy), with 986 men and women and 324 children on board.

The travelling conditions on the train were appalling: the cars were normally used to transport livestock and hundreds of Jews were crammed into them. Besides that, the prisoners had no food or water during the journey, which lasted three days and two nights. Many unfortunate people died of malnutrition, diseases or suicide. The corpses were intermingled with the people still alive, which made the journey even more traumatic.

When they arrived and got off the train, the SS made a selection. Men were sent to one side, women to the other. Rosa was separated from her husband and her sons, who were sent to the Auschwitz camp. She was also separated from her daughter Marie, who was selected to go to the Birkenau camp, while she herself was sent to the “showers”. We can only imagine what Rosa’s last hours were like. She was all alone, without her loved ones, in the midst of a crowd of strangers. They are taken to a large room where they had to get undressed in front of people they didn’t know. And then they had to go into the showers, in which no water ever flowed, but instead the soldiers poured in Zyklon B gas. Rosa must have felt the air thinning, her life ebbing away, and death looming. Afterwards, her corpse was incinerated in the crematorium and her ashes were intermingled with those of over a million other people.

At the age of just 45, Rosa lost her life; the Nazi system condemned her simply for having been born.

Français

Français Polski

Polski