Sommer GINZBURG

Putting together Sommer Ginzburg’s biography was no easy task, as our research was often held up by delays in receiving replies from various Memorials, needing to use pay-per-view sites, and then by the upcoming baccalaureate exams, which prevented us from continuing the project.

Let us begin at the beginning. We, Lucie, Valentine, Raphaël, Thibault and Maxime were in our final year at the Cassini high school in Clermont, in the Oise department of France, when our history and geography teacher, Ms. Limonier, suggested we explore the theme of micro-history. The idea was to focus not on a large scale, nor a major event, but rather on a small group of people, and one individual in particular. Given the choice between piecing together the lives of some children who were kept hidden in the Oise department, or writing the biography of a man who lived there, Ms. Limonier chose the second option. And so we began our research, meeting every Monday afternoon. To begin with, we had very little information about Sommer Ginzburg. According to the Convoy 77 website, he was born on August 1, 1897 in Walsilishki, in present-day Belarus. He later lived in the village of Ressons-sur-Matz and was arrested in Compiègne, both in the Oise department, at the age of 46. Ms. Limonier, who saw we were stuck, suggested that we look up Sommer Ginzburg in the most recent census in the Oise departmental archives, and this gave us a starting point for our research. Meanwhile, she contacted the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, in Normandy. They sent us sixty or so documents, and our work as historians could then begin in earnest.

First of all, we sorted the records and wrote down the significant dates in order to retrace this man’s journey. We wrote numerous e-mails to memorial organizations such as the Shoah Memorial in Paris, the Arolsen archives in Germany, the Memorial of Internment and Deportation in Compiègne and the Shoah Memorial in Drancy. We also contacted the town hall in Ressons-sur-Matz, and lastly, we attempted to contact the town hall in Walsilishki, but to no avail. We then tried to contact some of the small shops in the area, but none of them spoke English. We did not give up, however, and emailed the French Embassy to ask if they had any information about Sommer Ginzburg but, as expected, we never heard back from them.

A few months went by and then our baccalaureate exams were coming up, so had to concentrate on our revision. Unfortunately, this meant we had to stop working on Sommer Ginzburg’s biography.

We would like to thank the Memorial organizations for responding to our requests, and Ms. Limonier for her guidance during the project.

Ms. Limonier continues:

During the summer vacation, as I didn’t have a job lined up, I decided to continue the research. We had gathered a lot of information and records and I felt it would be a shame not to finish the biography. I had not forgotten that the biography was also intended to be a tribute to Sommer Ginzburg. As a Holocaust victim, he deserved to be honored and respected, something that the Nazis had denied him during his lifetime.

I realized that we had no photographs of Sommer Ginzburg to illustrate the biography or to put a face to the name of the man we had been focusing on for the past few months. I therefore decided to turn to the social networking site Facebook in an attempt to track down his family. When I saw that his name was often entered in the search bar, and thus there was very little chance of finding any of his relatives, I concentrated instead on his wife’s family name, Bezborodko.

I found a large number of people with this surname, so decided to do everything I could and sent a message to around twenty of them. A few days later, I received a reply from Louise Bezborodko, who told me she was related to Sommer Ginzburg’s wife, but that she was not able to give me much information, so she gave me her great-uncle’s phone number. At that point, the project became more of a personal quest for me. Jacques Bezborodko was one of Sommer Ginzburg’s nephews, but he had never met him. Nevertheless, he and another of his cousins, Joseph Rober, helped me enormously in completing their uncle’s biography.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their help with this project, and in particular for all the research they did in their spare time in order to unearth some records and photographs of their uncle. They also kindly agreed to review their uncle’s biography before I sent it on to the Convoy 77 organization for publication on the website. Thank you both for the trust you placed in me and for your time. I hope to have paid a fitting tribute to your uncle and your family.

Sommer Ginzburg

Sommer Ginzburg was born on August 1, 1897, in Wasiliszki, in Poland (now in Belorussia).

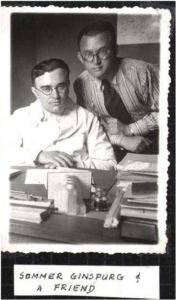

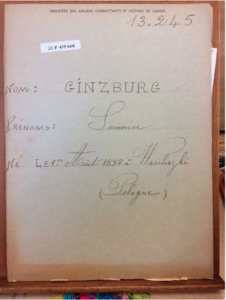

The first photo is of Sommer Ginzburg, on the left, seated, in white, was sent to me by his wife’s family. The second image was sent by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

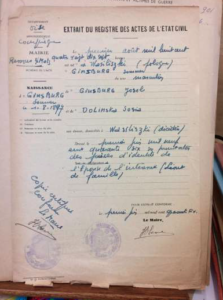

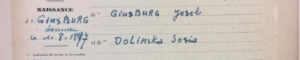

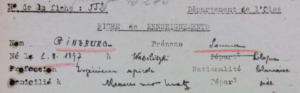

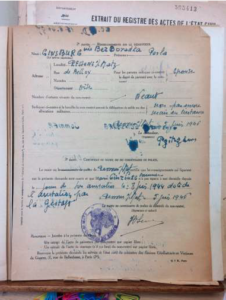

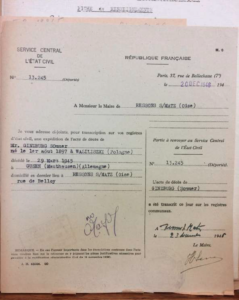

Extract from the French civil registry, dated June 1, 1945, listing Sommer Ginzburg’s parents’ names and his date and place of birth.

He was the only child of Josel Ginsburg and Sosia Dolinska, a Polish Jewish family.

Sommer Ginzburg’s birth certificate, dated June 1, 1945, listing his parents’ names and his date and place of birth.

Hitler’s rise to power: a dangerous time for Jews

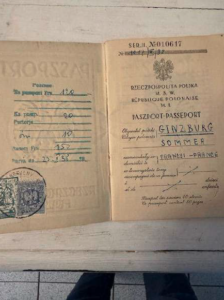

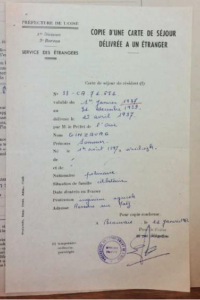

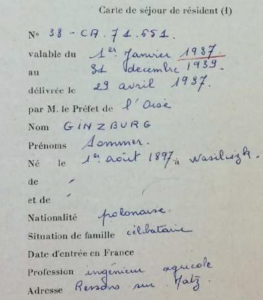

The early 1930s marked the onset of widespread anti-Semitism in Europe, particularly in Germany, where Adolf Hitler became Chancellor on January 30, 1933. His rise to power brought with it a wave of anti-Semitism in Western Europe, in addition to the anti-Semitism that was already prevalent in Russia. Suddenly confronted with this outpouring of hatred, large numbers of Jews emigrated to the USA, Palestine and France. Sommer Ginzburg was among them: he saw the danger brewing in his native country, and decided to flee to France in 1936. He soon applied for a residence card, which was issued on April 27, 1937, and stated that he was single at the time.

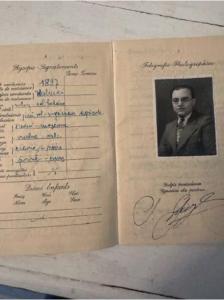

Samuel Ginzburg’s foreigner’s residence card, issued by the Prefecture of the Oise department of France. The copy was made on January 21, 1964 in Beauvais, also in the Oise department.

Sommer Ginzburg went on to study agronomy at the prestigious National Agricultural School in Nancy, in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France. It was there that he met Perla Bezborodko, a young Russian Jewish woman, whose parents were Joseph Bezborodko and Macha Peremoling. Perla was born on May 19, 1910 in Lodz, a large town in Poland with a population of around 600,000. Known within the family as “Paula”, she married Sommer Ginzburg on February 23, 1942 in Ressons-sur-Matz. The wedding took place during the Second World War, and the area had been occupied by the Germans since May 10, 1940.

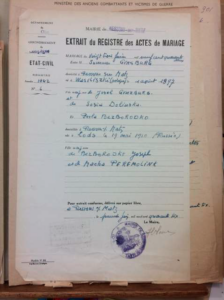

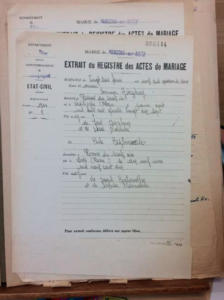

Copies of pages from the marriage register, made by the Ressons-sur-Matz town hall on June 1, 1946. The one on the left is in the name of Sommer Ginzburg and the one on the right is in the name of Perla Bezborodko, his wife.

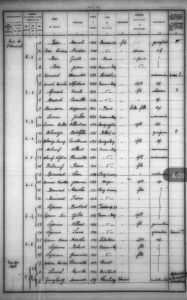

At the time of the 1936 census, Samuel Ginzburg was living at 3, rue du Bail in Ressons-sur-Matz. This was the last census he was ever listed in.

Screenshot from the Oise departmental archives, featuring a page from the 1936 census of Ressons-sur-Matz. Sommer Ginzburg is listed on the last line.

Sommer Ginsburg was an agricultural engineer there, responsible for the working with the farms that made up the Matz Valley dairy, butter and cheese cooperative.

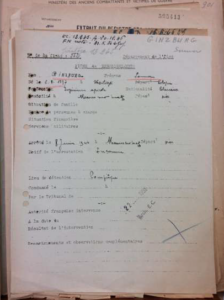

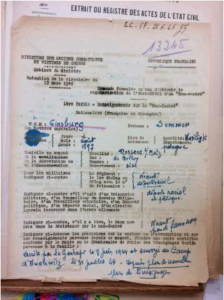

Information sheet on Sommer Ginzburg, drawn up when he was arrested on June 8, 1944, including his identity and occupation at the time.

The first time he was arrested: May 20,1943

Sommer Ginzburg, then aged 46, was arrested for the first time on May 20, 1943, in the village where he lived. He was then taken to the Royallieu camp in Compiègne, where was held for 9 days, during which time his name was replaced by a serial number, 42,639.

On May 29, 1943, he was freed from the Royallieu camp thanks to his employer, who was well respected by the authorities and was able to negotiate his release.

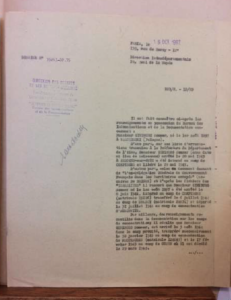

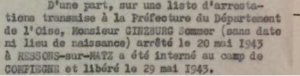

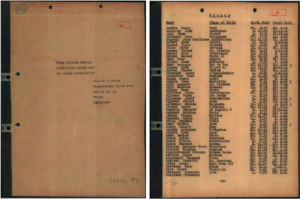

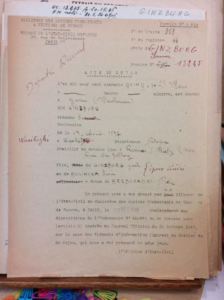

The first document provides evidence of Sommer Ginzburg’s first arrest and release in May 1943; it was produced on June 24, 1952. The second is a typed account of Sommer Ginzburg’s arrest record up to the time of his death, including the first arrest on May 20, 1943.

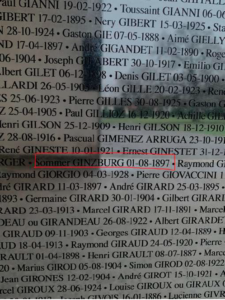

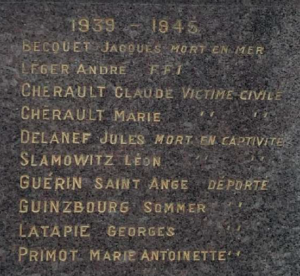

Photograph of the “Wall of Names” bearing the names of all the people who passed through the Royallieu transit camp. Photo taken by Ms. Limonier on February 10, 2024.

“Information sheet on a person arrested by the occupying authorities” drawn up at the time of Sommer Ginzburg’s first arrest.

An anonymous tip-off, the last time Sommer Ginsburg would ever be a free man: June 8, 1944

Sommer Ginsburg was arrested for the second time on June 8, 1944, just two days after the Allies landed in Normandy. Someone had reported him to the Gestapo on account of his “Jewish nationality”.

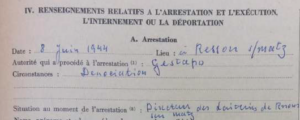

Copy on the “information relating to execution, internment or deportation”, which states that the Gestapo arrested Sommer Ginsburg for the second time on June 8, 1944, as a result of an anonymous tip-off.

Continuation of the copy of the “Information on execution, internment or deportation” drawn up at the request of Perla Bezborodko, Sommer Ginzburg’s wife. Again, it states the date and circumstances of the arrest.

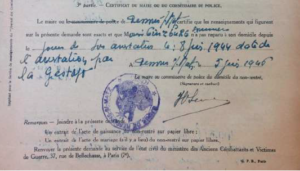

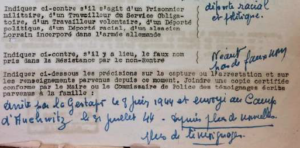

A document issued after Sommer Ginzburg’s wife asked the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War to declare him a “non-returned person” and a “racial and political deportee”. On the bottom, written in fountain pen, it says: “Arrested by the Gestapo on June 8, 1944 […]. Since then, no further news, no further sightings.”

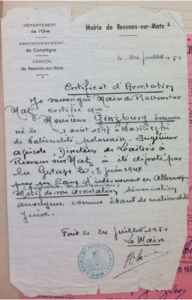

Document drawn up by the mayor of Ressons-sur-Matz on July 24, 1950, confirming that one of the residents of the village, Sommer Ginzburg, was arrested on June 8, 1944.

Once again, Sommer Ginsburg was interned in the Royallieu camp. This time, his serial number was 15,126.

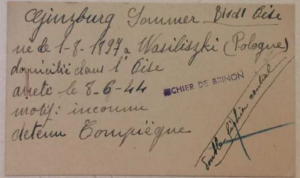

Handwritten note providing information on the place in which Sommer Ginzburg was being detained.

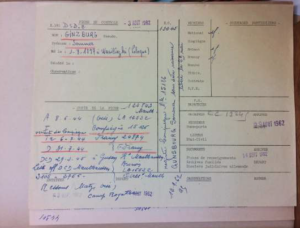

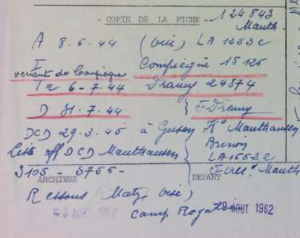

This 1962 “Verification sheet” retraces Sommer Ginzburg’s journey following his arrest on June 8, 1944. The second line of the cropped and enlarged image reads “Compiègne 15 126”, meaning that he was sent to the Royallieu camp, and his serial number there was 15,126 .

From there, on July 6, 1944, he was transferred to Drancy camp, north of Paris, where he was assigned the serial number 24,874, and put in a room the 5th floor on staircase 18.

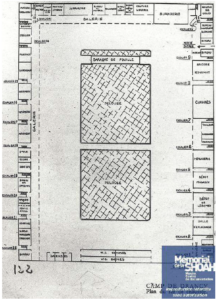

Plan of Drancy camp.

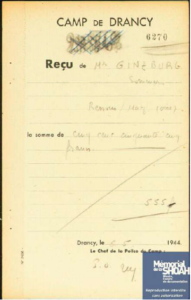

Sommer Ginzburg’s receipt from Drancy camp. When internees first arrived, they were searched and had their property confiscated. It appears that Sommer Ginzburg had 555 francs taken from him.

Deportation: the fatal journey

On July 30, 1944, the day before they left, Sommer Ginzburg and the other prisoners scheduled to be deported were all put in one area of the camp. It was on the 2nd floor on staircase 22, which had been set aside people being sent to the concentration camps. The following morning, they were gathered in a courtyard that was off-limits to other inmates, where buses were waiting to take them to Bobigny station. French military police officers accompanied them as far as the station, where they were handed over to the Germans. [3]

[On July 31, 1944, Sommer Ginsburg was deported on the last large transport from Drancy: Convoy 77. With over 1,300 Jews, including 330 children on board, the convoy set off from Paris-Bobigny station, which was the departure point for all rail transports to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp between July 1943 and August 1944.[4]

The French National Railway Company (SNCF) played a significant role in deporting Jews, and very few French drivers declined to participate in the deportations. One of those who did, however, was Léon Bronchart, who refused to drive the train.

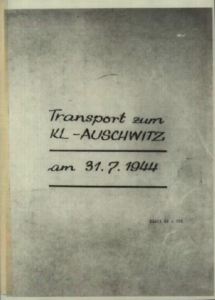

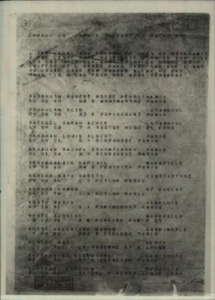

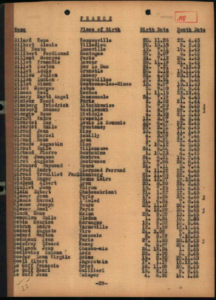

The Convoy 77 deportation list. The cover page says “Transport to KL-Auschwitz, 31.7.1944” and “Convoy from Drancy departing on 31 07 44” is written at the top of the first page of the list. Sommer Ginzburg’s name is on the second page, on the eighth line from the bottom.

With 50 or 60 people crammed into each of the 20 or so wagons, many died of exhaustion or the extreme heat, especially on Convoy 77. The journey took around 55 hours, and the deportees were given very little water. The dehumanization of deportees began even on the train: treated like animals, they were herded into cattle cars, given little food and forced to relieve themselves in front of all the others, thus losing what little dignity they had left.

On August 3, 1944, after a long, arduous journey, Sommer Ginzburg and the other deportees arrived at the Auschwitz concentration camp and killing center, around 40 miles west of Krakow in Poland.

Screenshot of the route taken by Convoy 77.

After Convoy 77 left Bobigny station, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, the train passed through Novéant sur Moselle station in France, Saarbrücken, Frankfurt am Main, Fulda, Erfurt, Leipzig, Dresden, Goerlitz and Cosel stations in Germany and Katowice station in Poland before it finally arrived in Birkenau.[5]

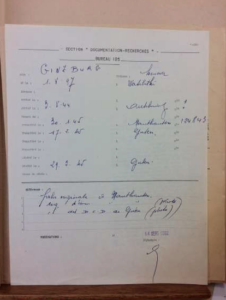

A record entitled “Section ‘Documentation-Research’”, which lists the dates of Sommer Ginsburg’s arrival and departure dates for each of the camps. It states: “Arrived on: 3.1.44 in Auschwitz”.

When the deportees arrived in Birkenau, the selection process took place immediately. Sommer Ginzburg, who was deemed fit for forced labor, was spared being sent straight to the gas chambers. However, there is no information available about his life or the work he was forced to do in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

As Nazi Germany fell from power, prisoners were moved from camp to camp

On January 12, 1945, the Red Army launched a major offensive, with the objective of taking Berlin in fewer than 45 days. The Nazis, realizing that their power was waning as the Russians advanced, decided to move the Auschwitz prisoners to other camps, including the Mauthausen camp in Austria.

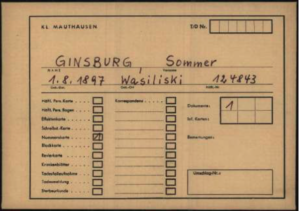

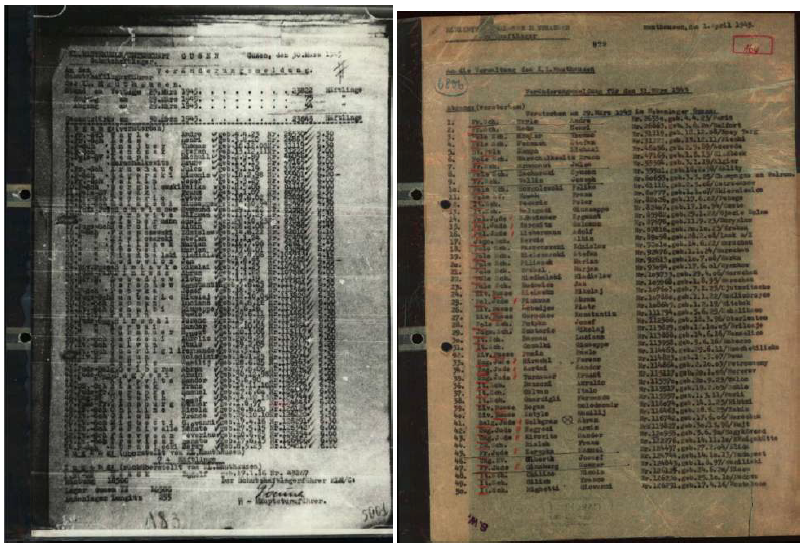

The first convoy arrived in Mauthausen on January 25, 1945. 5 days later, on January 30, Sommer Ginzburg also arrived in Mauthausen, where he was assigned the serial number 124,843.

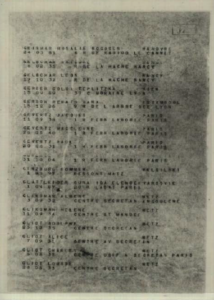

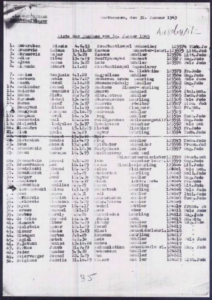

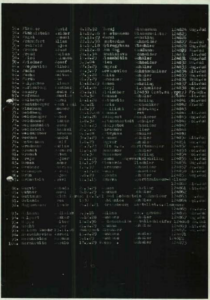

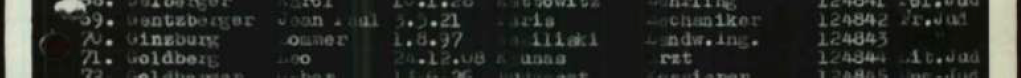

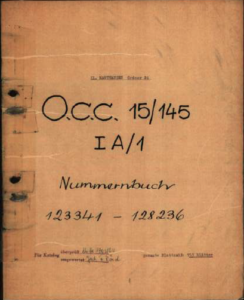

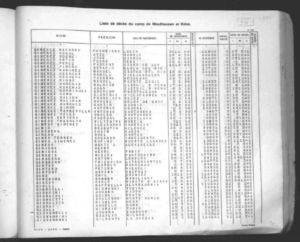

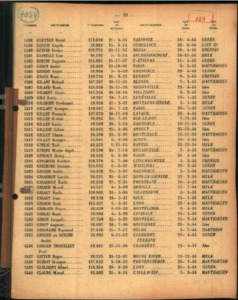

An official Mauthausen concentration camp record entitled “Liste der Zugänge vom 30. Januar 1945” (the title at the top of the first page of the list), which means ‘’List of arrivals on January 30, 1945‘’. It is dated the day after the convoy arrived: “Mauthausen, den 31, Januar 1945” (on the top right of the first page). Sommer Ginzburg is listed as number 70 on the second page – see the enlarged image.

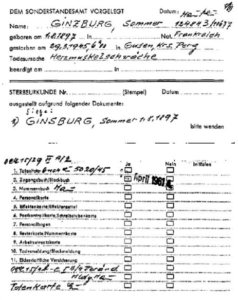

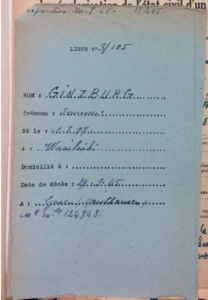

Mauthausen camp record for Sommer Ginsburg.

Thousands of prisoners died over the 3-day journey, not only as a result of the cold weather, but also due to their already poor physical health. “In Mauthausen, most of the Jews deported from France were registered as French, whereas inspection of the application files for political deportee or resistance fighter status, as well as the civil status rectification files, reveals that 36% of them were in fact of foreign nationality (most of them Polish)”.[6]

Sommer Ginzburg was thus listed as Jewish and French, whereas he should have been identified as Polish despite the fact that he had become a French citizen a few years earlier.

Mauthausen and its annex camps: a slow death from exhaustion

Mauthausen was categorized as a “level 3” camp, meaning that the system there was much tougher than in most other camps.[7]

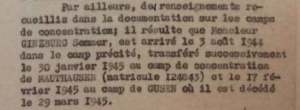

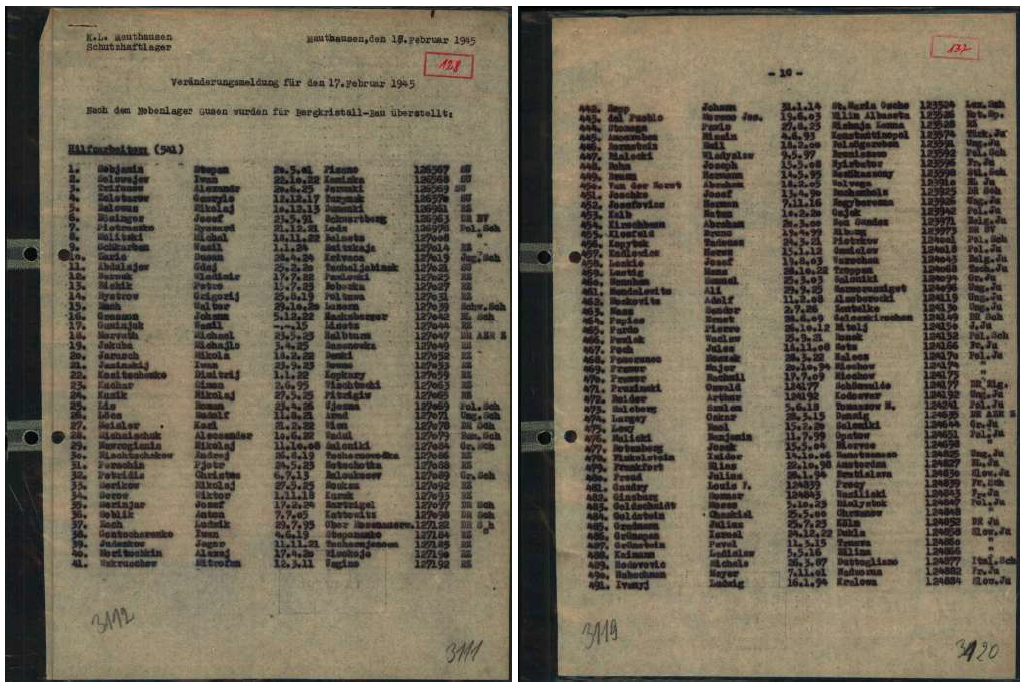

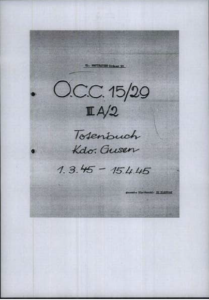

Most of the prisoners transferred to Mauthausen were sent there to be exterminated through forced labor (“Vernichtung durch arbeit”). Mauthausen had several annex camps, the most well-known of which were Gusen I, Gusen II and Gusen III, which were not far from a stone quarry. Sommer Ginzburg was on the list of prisoners selected to work there, and on February 17, 1945, he was moved to the Gusen Kommando.

A record of Sommer Ginzburg’s movements following his last arrest. The enlarged image shows that he was transferred on “February 17 to the GUSEN camp”.

Screenshot of an “aerial view of Gusen I, II and the Steyr Kommando”.

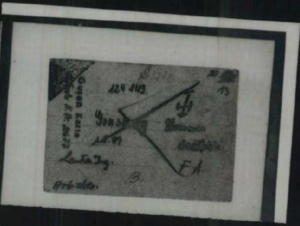

“Gusen Karte”, or “Gusen card”, in the name of Sommer Ginzburg, featuring his name and his registration number. It appears to be quite a small card and has a cross in the middle, which was probably added after he died.

Many prisoners in Gusen were put into one of two workgroups: the first hewed out granite, while the second hauled the blocks out of the “Wiener Graben” quarry, having to climb up and down a 186-step set of stairs. SS soldiers looked on intently, and sometimes pushed prisoners from the top of the quarry, just for their own amusement.[8][9]

Sommer Ginzburg, however, was sent to the Gusen II camp and forced to work on the Bergkristall-Bau tunnel construction project. The tunnels were to be underground facilities for the production of Messerschmitt fighter planes.

Official records from the Gusen concentration camp, typed on February 18, 1945. The title: “Nach dem Nebenlager Gusen wurden für Bergkristall-Bau überstellt” (at the top of the first page of the list) means: “From the Gusen subcamp, they were sent to the Bergkristall site.” Sommer Ginzburg is listed as number 482 on the second image.

Killed by Nazism

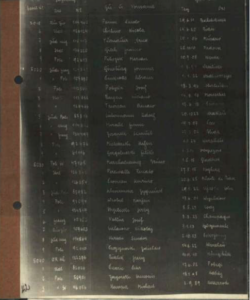

On March 29, 1945, the SS soldiers in charge of prisoner roster changes entered Sommer Ginzburg’s name on the list of deceased prisoners. The record states he died of “heart muscle weakness”, but it is not clear if it happened at 6:00 a.m. or 6:00 p.m. It was only about a month before Mauthausen was liberated. In the end, it was neither the Americans nor the Russians who liberated Mauthausen and its Kommandos, but rather, in the words of Jacques Bezborodko’s father: “We woke up in the morning and the SS had disappeared. We waited almost 48 hours before leaving the barracks, and then it was a case of kapo hunting.” The Gusen Kommando was liberated on May 5, 1945, 17 hours after Mauthausen.[10]

Information sheets on Sommer Ginzburg, from the International Tracing Service office in Bad Arolsen, Germany. The second and fourth sheets contain information about his death: “Todesursache: Herzmuskelschwäche”, meaning “Cause of death: Weak heart muscle”.

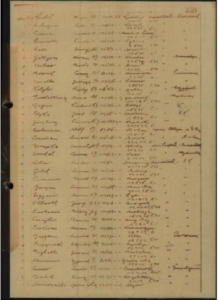

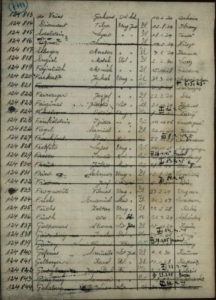

Mauthausen concentration camp daily log, dated March 30, 1945. No. 47 on the list is Sommer Ginzburg, who is recorded as deceased.

Handwritten register of deaths at the Mauthausen concentration camp and its annex camps, including Sommer Ginzburg: number 124,843

Mauthausen concentration camp register, which appears to have been altered after Sommer Ginzburg died. His name is second from the bottom, but the whole line has been crossed out and his date of death is written above his date of birth.

Death register from Mauthausen concentration camp and its annex camps. Sommer Ginzburg: N° 5020, serial number 124,843

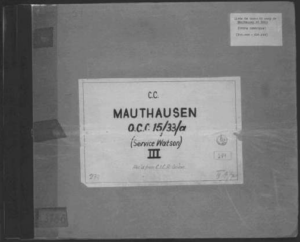

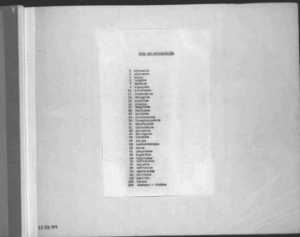

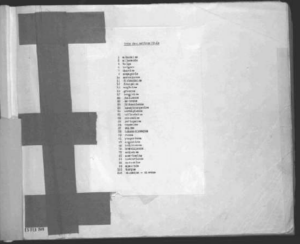

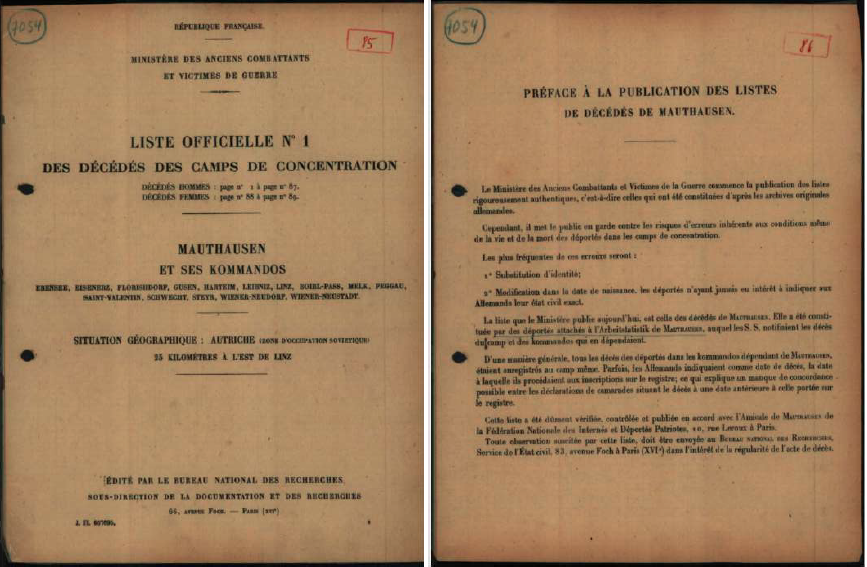

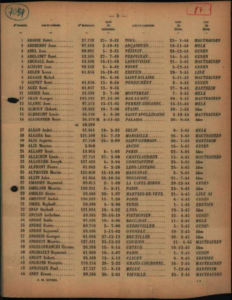

Front cover, nationality codes list and list of prisoners who died in the Mauthausen concentration camp and its Kommandos. Sommer Ginzburg’s name is on the 8th line.

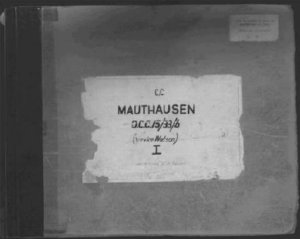

Front cover, victim categories list and alphabetical list of prisoners who died in the Gusen Kommando camps linked to the Mauthausen camp. Sommer Ginzburg’s name is on the 28th line.

Front cover, list of nationality codes, alphabetic list of prisoners who died in the Mauthausen concentration camp and its Kommandos, book 1. Sommer Ginzburg’s name is 13th from the bottom.

“Judge advokate sektion third unites states army war crimes investigation”= ”Section du juge-avocat, troisième enquête sur les crimes de guerre de l’armée américaine”. Liste alphabétique des victimes du camp de concentration de Mauthausen, également classées par nationalité (ici les français) c’est notamment une liste rédigée d’après guerre par l’armée américaine. Sommer Ginzburg: 17ème à partir du haut de la liste.

List of people who died in the Mauthausen concentration camp. This list was drawn up by the French Ministry of Veterans’ and Victims of War after the war. Sommer Ginzburg’s name is on the second list, number 1522.

Sheet listing the date and place of Sommer Ginzburg’s death.

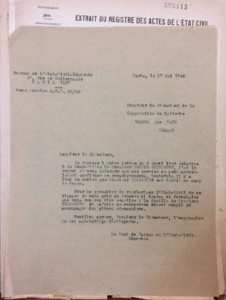

Official French record confirming the death of Sommer Ginzburg, including the date and the place of death.

Sommer Ginzburg’s death certificate, issued by the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and War Victims on December 20, 1946.

Lastly, on the French government legal website, Légifrance, a search bar provides access to a decree dated July 6, 1993, which provided for the words “Died during deportation” to be added to Sommer Ginzburg’s death certificate: “Ginzburg (Sommer), born August 1, 1897 in Wasiliszki (Poland), died March 29, 1945 in Gusen (Austria)”. [11]

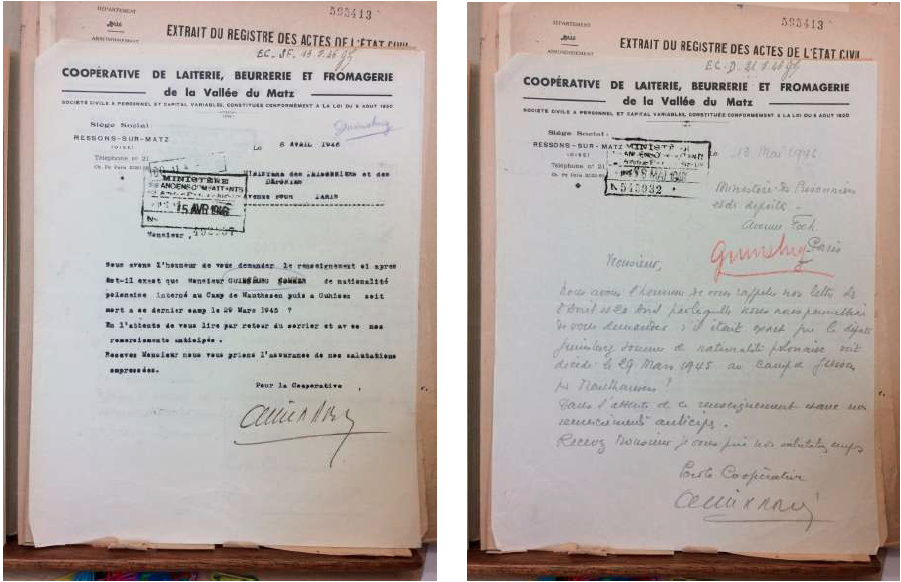

On April 8, 1946, the manager of the dairy cooperative where Sommer Ginzburg worked as an agronomist wrote to the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War, requesting confirmation of his death.

Typewritten and handwritten letters from the manager of the dairy cooperative.

Reply from the Head of the Civil Status Bureau for Deported Persons, dated May 17, 1946.

Sommer Ginzburg: a man who must never be forgotten

Sommer Ginzburg was an exceptionally good man, a saint of a man, according to those closest to him. He was well-liked by everyone, and his employer had him released after he was arrested for the first time. However, a year later, someone reported him to the Gestapo on account of his religion. Forced to leave his wife, Perla, and his family behind, Sommer Ginzburg died in a Mauthausen annex camp on March 29, 1945. During the “Holocaust” or “Shoah” (the Hebrew word for “Catastrophe”), around six million Jews were exterminated due to the deep-rooted anti-Semitism that prevailed in Nazi Germany. Sommer Ginzburg was among them.

After the concentration camps and killing centers were liberated, his wife, Paula, applied to the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War to have her husband recognized as having been deported for political reasons, on grounds of his “race”.

“To forget would not only be dangerous but offensive: to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time. And if, the killers and their accomplices excepted, no one is responsible for the first death, we are responsible for the second.” From “The Night”, by Elie Wiesel.

Photos taken on Sunday, September 1, 2024, in Ressons-sur-Matz.

The first photograph shows the whole war memorial from the front. The second is of the side of the monument, on which, as can be seen in the close-up, Sommer Ginzburg’s name is inscribed.

Sources

- (1): Sommer Ginzburg’s wife’s family archives: photo of Sommer Ginzburg.

- (2): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (3): Sommer Ginzburg’s wife’s family archives: photo of Sommer Ginzburg.

- (4): Sommer Ginzburg’s wife’s family archives: photo of Sommer Ginzburg.

- (5): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (6): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (7): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (8): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (9): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (10): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (11): Photo of the “Wall of Names” at the Royallieu Memorial to Internment and Deportation, taken by Ms. Limonier on February 10, 2024.

- (12): Photo provided by the Royallieu Memorial to Internment and Deportation.

- (13): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- (14): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (15): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (16): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- (17): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (18): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (19): Photo of a photocopy provided by the staff during a visit to the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

- (20): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (21): Screenshot of the route taken by Convoy 77, from the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center website.

- (22): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (23): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (24): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (25): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- (26): Screenshot of the “aerial view of Gusen I, II and the Steyr Kommando”.

- (27): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (28): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (29): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (30): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (31): Photo provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (32): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (33): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (34): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (35): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (36): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (37): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (38): Photos provided by the Arolsen Archives service.

- (39): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (40): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (41): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (42): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (43): Photo provided by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen: GINZBURG_Sommer_21_P_455_668_14852.

- (44): Photographs taken by Albane Aubin.

Links

- [1] https://archives.oise.fr

- [2] https://www.memorialdelashoah.org/

- [3] https://garedeportation.bobigny.fr/

- [4] https://garedeportation.bobigny.fr/

- [5] https://collections.yadvashem.org/

- [6] https://monument-mauthausen.org/

- [7] https://www.mauthausen-memorial.org/

- [8] https://www.jewishgen.org/

- [9] https://www.monument-mauthausen.org/

- [10] https://francearchives.gouv.fr/

- [11] https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/

Français

Français Polski

Polski