Zalo GOURENZEIG

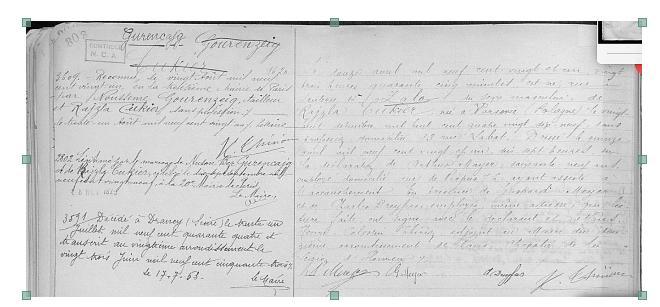

On the left, Zalo’s birth certificate. Source: Paris archives

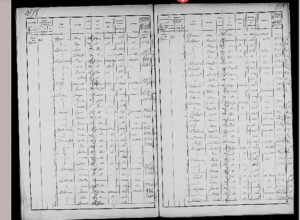

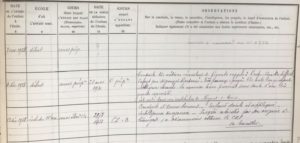

Zalo Gourenzeig or Gourencajg was born on April 12, 1921 in Paris, France. He was the eldest son of Rosa and Noussen, immigrants from Poland. The name Zalo was not the one chosen by the family. In fact, Noussen and Rosa wanted to call their son Zale, but the city employee misspelled the name on account of Noussen’s accent. According to Paulette, Zalo’s younger sister, people soon made fun of this name: Zalo, meaning bastard. This explains why Noussen and Rosa then called their son André. According to the 1931 census, the family lived at 397, rue des Pyrénées, in the 20th district of Paris. It was a cosmopolitan neighborhood. Zalo went to school at 104, rue de Belleville. According to the school register, little Zalo was a “docile and diligent” student, but his progress was “held back by his foreign background”. Yet according to his younger brother, Joseph, Zalo’s subsequent school reports were excellent.

Extract from the 1931 census. Source: Paris Archives

Extract from the register of the school on rue de Belleville. Source: Paris Archives, ref. 2846W 7

Zalo was influenced by Abraham, a first cousin who was raised by his parents and was a Trotskyite. He then became a communist. His political interests and involvement meant that he became very interested in the ideas of his political enemies. He read Mein Kampf, for example. Following the invasion of Poland, he quarreled with his father, whom he was unable to convince of the danger and advisability of moving to the United States. After that incident, he stopped speaking at all, and his father called in a psychiatrist, who had Zalo admitted to a care home for further examination. Noussen then realized that it was not the right place for his son, and took his son out of the home.

In the spring of 1940, his father sent him and the rest of the family to take refuge in a small village near Sens. They stayed with an elderly English woman. During his time there, Zalo devoured some of their host’s books. They all returned to Paris a few days later, just before the Germans invaded in the city.

In 1941, Joseph, along with all of his family members, lost his French nationality under the terms of the French decree dated July 22, 1940. According to an article in the French newspaper Le Monde: “The law of 1940 […] officially concerned “the revision of naturalizations” but its first section referred to “the revision of all acquisitions of French nationality“. This is quite different, since naturalization and the acquisition of nationality are not at all the same thing. Firstly, in terms of numbers, there are twice as many people who acquire French nationality as those who are naturalized. Secondly, legally, the children of naturalized French parents are born French, whereas naturalized persons are born foreigners”.

After they lost their French citizenship, Joseph’s father decided to look for a place to relocate his family in the free zone14. He found a place to live in Lyon and sent a “people smuggler”, or trafficker, to Paris to bring his family to join him. Joseph’s sisters were the first to arrive at the Gare de Lyon station in Paris, where Joseph, his brother and his mother were to meet them. However, the family could not find each other. His mother therefore got off the train in Dijon in order to go back to Paris to find her daughters, while Zalo and his brother Joseph continued their journey with the trafficker.

Zalo and his brother were alone on the train with the trafficker. They got off the train just before Chalon-sur-Saône to try to get across the demarcation line, which was the border between the German-occupied zone and the non-occupied free zone to the south. The demarcation line crossed thirteen French departments and was nearly 750 miles long. It was only possible to cross the demarcation line legally by submitting a lengthy application to the German occupation authorities for an Ausweis (identity card) or a Passierschein (pass), which were very difficult to obtain.

Zalo and his family decided to cross the demarcation line in secret, with the help of the people smuggler, but they were arrested by the Germans and locked up in Chalon-sur-Saône prison, where they were kept in cells. Zalo was lucky that he was with Joseph. They were interrogated in turn. They were given very little to eat and were only allowed out for 30 minutes on the first day. There was only one water closet per cell. It is very cold and there were no blankets. They had only two hours of free time per day. Joseph managed to find some bread for Zalo, but Zalo was then moved to another cell, so was no longer with his brother.

They were then transferred to Autun prison, where they were interrogated again. In Autun, the atmosphere was much better than in Chalon: the cell doors were left open all day long, and the prisoners could play cards in the refectory if they wanted to. During his time there, Zalo appeared to be lost in thought. After a while, the Jewish prisoners were taken on foot to the nearest prefecture. They were interrogated again and Joseph and Zalo were allowed home. They stayed there for eight weeks in all.

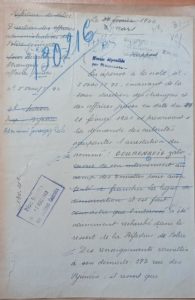

Zalo and his brother returned to Paris to join their mother and sisters. On their first night there, their mother, fearing the arrival of the police, hid Joseph and Zalo in the maid’s room. The next day, at 5 a.m., the police questioned their mother, asking where her sons were. The police abandoned the search for the time being. However, records show that they returned to the Gourenzeig’s house later on, still hunting for Zalo and his brother.

Internal memo from the Department of Foreigners and Jewish Affairs. Source: Paris Archives, ref. 77W213-130216

Meanwhile, on the same day, their mother took Joseph and Zalo to see their aunt, who lived on boulevard Richard-Lenoir. Their aunt found them another people smuggler to take them across the demarcation line. The smuggler took them by train, made them wait in a bar and then they set off on a long walk in the snow. At daybreak, the smuggler told them that they were in the free zone. A peasant woman took them in and fed them, and then the police interrogated them and put them on a train to Lyon. At last, they got there and were able to join their father and move in with him at 11 place Antonin Gourju, in the center of Lyon, on the banks of the Saône river. It was, however, near the place Bellecour, where the Gestapo was based.

Since he was not registered as being Jewish, Zalo was sent to the youth camps, from which he escaped. He then had to live in hiding and had a forged medical certificate made up so that he would not have to go back. The youth camps were ambiguous institutions, designed to instill the ideals of the Vichy regime into the young people. They were introduced on July 30, 1940. They were only open to young men over the age of 20 from the Free Zone and French North Africa, who were sent there for a six-month internship. They lived in the same way as scouts, in camps, but they were not there voluntarily. They did forestry work as a community service in an army-like environment.

Zalo took a keen interest in politics; he listened to Radio London regularly. He told his family about the collapse of the German army on the Russian front. On June 6, 1944, he broke the news about the Normandy landings, and everyone was ecstatic. This time for sure, the war was almost over. Unfortunately, on July 18, 1944, as a result of a tip-off, Zalo’s parents and brother were arrested, even though less than two months later, on September 3, 1944, the city of Lyon was liberated. Hi sister, Marie, managed to escape and hid in her bedroom closet. The Gestapo men then returned to the apartment to steal the family’s belongings and it was at this point that they found Zalo30. He was sent to Montluc prison, where he was reunited with his father and brother. During his time there, the Gestapo agents beat him on numerous occasions.

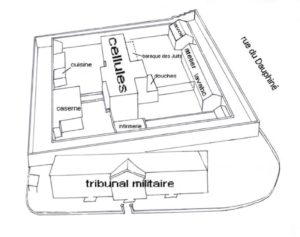

Montluc jail was at 4, rue Jeanne Hachette in the 3rd district of Lyon. It was originally built in 1921 as a military prison, on the slopes of the old Montluc Fort. It is well known for its role as a detention facility during World War II. Zalo was held in the “Jews’ barracks”, together with his father and brother. This was a building constructed of wooden planks and canvas, 100 feet long by 20 feet wide, in which Jews were crammed together in very harsh conditions.

The Jews’ barracks in the main exercise yard

Source: Rhône departmental archives, ref 4544 W 17

The location of the Jews’ barracks today. Source: Photo by Christèle Vial

Plan of the Montluc prison

Source: http://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media496-Plan-de-la-prison-de-Montluc-Lyon#fiche-tab

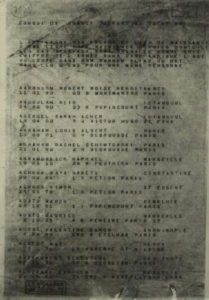

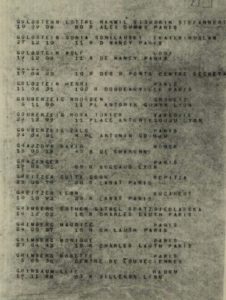

Except for Paulette, all of the Gourenzeig family was transferred to Drancy, a transit camp run by the Jewish Affairs section of the Gestapo. The camp, which was near Paris, was set up in August 1941. By the time it closed, in August 1944, nearly 40,000 Jews had passed through the camp and had been deported to Auschwitz. According to the French civil status records from July 17, 1963, Zalo died in Drancy camp on July 31, 1944, yet according to the list of deportees from Drancy, Zalo was put on the train, together with his family, to be deported to Auschwitz. His brother even reports that his mother was worried about her oldest son’s health. They were sent to Auschwitz in cattle cars, in which they took turns sitting or lying down due to lack of space and had no access to food and very little to drink. A lot of people died during the journey, which took three days and two nights. In addition, the lack of hygiene meant that various fatal diseases were able spread. Along the way, the “tinette” (a type of bucket in which the deportees relieved themselves) tipped over, which made the journey even more uncomfortable. One can imagine that the journey was hell for Zalo.

Extract from the list of deportees that left Drancy for Auschwitz on Convoy 77. Source: Copy of 1.1.9.9 / 11191135

in conformity with ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives

Alphabetical lists of Jews deported from transit camp Drancy (Original transport lists in possession of Bureau National de Recherches Francais)

In August 1944, the Gourenzeig family arrived at Auschwitz. An SS officer carried out the selection, sending the deportees to one of the two lines. The mother was sent to the line on the left, which was for those who were to be taken to the gas chambers. Zalo, despite the fact that he was limping, was sent to the line on the right, together with Mary, Joseph and their father. If the deportees were too weak or too slow, the Nazi soldiers hit the them to make them to move faster.

The prisoners were taken into the Auschwitz camp, where their personal belongings were taken away, they were shaved, washed, vaccinated, tattooed and given striped pajamas to wear, which was intended to strip them of their humanity and identity.

After that, they were put in quarantine, Zalo on the third floor of block A while Joseph and his father were on the second floor of the same block (see letter B in the primer). The prisoners slept in the dormitories with nothing more than a straw mattress for a bed. For their first meal, they had just a piece of black bread and, if they took too long to move, they were beaten mercilessly.

After that, they were sent to a stone quarry to carry out forced labor, which consisted of breaking stones all day long. The deportees who were unfortunate enough to stop were severely beaten. Their only respite was at lunchtime, when they were given warm soup containing vegetable peelings. Zalo was too sick and weak to feed himself, so his father fed him.

The evening meal was made up of a piece of black bread, a small piece of margarine and a bit of sausage.

One evening, a short while later, Zalo told his father that he wanted to put an end to this horror by taking his own life. He was desperate and could not stand it any longer. His father tried to convince him not to do it, pleaded with him to be patient and told him that he would be there for him. By this time, Zalo was at the end of his tether, he had no desire to live like that and above all, he no longer believed in anything, neither in a better future nor that life was worth living.

The following morning, Zalo was found dead in the snow under a window, frozen to the bone. According to Joseph, Zalo had thrown himself out of the window. However, since no one saw what happened to him before he died, it’s possible that someone pushed him, although that is unlikely given what he had said the day before.

HIs time in Montluc, Drancy and Auschwitz shattered this 23-year-old man and drove him to his death.

Français

Français Polski

Polski