Paulette JACHIMOWICZ

A photo intended to symbolize Paulette Jachimowicz, taken by the students.

Who was she?

A group of 9th grade students from the Jean de la Fontaine middle school in Le Mée-sur-Seine worked on the biography of Paulette Jachimowicz, a little girl of just 9 years old who was deported and killed.

As part of their research, the students visited the Shoah Memorial in Paris, where they listened to the testimony of Anna Koch, who was hidden as a child during the war. They then visited the Drancy memorial.

As there are no photographs of Paulette, the students produced an image that could be representative of her. Here’s their explanation: “We chose hopscotch because it’s a child’s game. The first three squares of the hopscotch symbolize Paulette’s short childhood, playing with toys. The further you go up the squares, the closer you move to her death, symbolized by the swastika, the convoy number and the barbed wire around the hopscotch court.”

Two students then wrote an imaginary monologue, spoken by Paulette, using her arrest in Saint-Mandé as a starting point.

I. Before the war

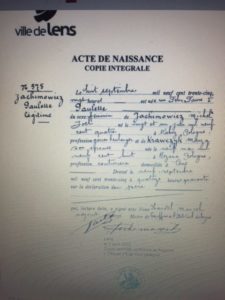

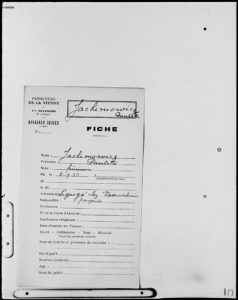

Paulette Jachimowicz was born on December 8, 1936 at 5 rue Félix Faure in Lens, in the Pas-de-Calais department of France. She was the only daughter of Michel Joël Jachimowicz and Maszak Krawczyk. Her father was born on June 21, 1904 in Kalisz, Poland, a town on the Prosna River in Wielkopolska. He worked as a baker’s boy. His wife was born on May 9, 1908, in Rogana, a town about 50 miles from Warsaw in northern Wielkopolska. She worked as a dressmaker.

Paulette’s father arrived in France in 1922, at the age of 18. Some of his relatives were already in France, and he sometimes stayed with them. He moved several times to various towns in the Lorraine region of France: first to Metz and then to Thionville in 1923. From there, he moved to Saint Avold, then to Etain in 1925, to Homécourt in 1932 and then back to Metz before moving to Toul on May 15, 1934.

Paulette’s parents were married in Argenteuil in the Seine-et-Oise department of France on November 24, 1934. They lived at 6 rue de la chaussée in Montigny-les-Metz. They got divorced four years later, on June 8, 1939, but had probably separated before that date given that mother and daughter left Lens as early as 1936, without the father. There is no trace of him after this.

Masza Jachimowicz went to stay with Aizyk Jachimowicz at 22 rue du Champé in Metz on January 21, 1936. On February 20, 1936, she moved to 7 rue Serpenoise and then nine days later she went to stay with some people called Mekler or Keller at 7 bis rue des Allemands. She left them on November 7, 1936, but we have no details of where she went after that.

Paulette lived in Lens for the first four months of her life and then on January 26, 1936, she went to live with the Batry family on rue des Minimes in Metz (although we are not certain of that since the handwriting on the census form is barely legible). On May 26, 1936, Paulette left rue des Minimes for Marange, a town about 12 miles from Metz, possibly to live with a nanny.

II. The war

1) The exodus to the west of France

We gathered this information from the testimony of Félicia Barbanel, who travelled the same path as Paulette. We assume that Paulette and her mother also took a refugee train, since they lived close to the German border, as part of a plan to evacuate people from the eastern border areas of France. This was a military operation, organized by the French authorities.

The train journey to the Bordeaux took three days. Paulette and her mother were then taken to Les Billaux, about 5 miles from the town of Libourne. We can confirm this as we have documentary proof. We suppose that Paulette and her mother were housed in a large, middle-class home where they were allocated a room to live in. They were eligible for refugee benefits, although their names do not appear on the list of claimants. We also assume that Paulette went to the local school in Les Billaux, where they stayed until the Germans invaded France. Félicia Barbanel reports that a number of people from the Alsace and Lorraine regions were evacuated to Berthegon in the Vienne department of France. This was the last place that Masza, Paulette’s mother, ever lived. The Jews had to check in every day at the town hall in Berthegon.

2) The internment camp in Poitiers

The Nazis arrested Paulette and her mother along with all the other Jews and took them to an internment camp in Poitiers. They arrived there on July 15, 1941. The living conditions in the camp were horrific: there was a shortage of facilities, heating and food and diseases were rife. The clay soil turned to sticky mud in wintertime. By mid-July 1941, 309 Jewish adults and children were interned there.

3) Masza was deported

On July 8, 1942, Paulette’s mother, like Félicia Barbanel’s, was deported on Convoy 8 from Angers to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

We note that Paulette went back and forth to the camp several times, in between staying with host families, no doubt thanks to the efforts of Rabbi Bloch. Paulette may have passed through the children’s home at “La Sansonnerie” in Migné-Auxances, about five miles from Poitiers. In a letter written to Rabbi Bloch, Masza asked that her daughter be placed with her sister-in-law, a Ms. Wachtel, in Angoulême, after she left Migné. However, there is no record of this in the Poitiers camp registers.

4) The host families

a) The Rosenchein family

On November 26, 1941, Paulette was taken in by a Jewish family, since the Germans strictly forbade the placement of Jewish children other than with Jewish families (although in some cases, non-Jewish families were also allowed to take them in). Host families were often like a second family to the children. They tried to make the children’s day-to-day lives more bearable.

Paulette was initially placed in foster care with the Rosenchein family in Ligue, a village about five miles south of Poitiers in the Vienne department in what is now the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of France. She was placed with this family together with Georgette and Nina Krieger and Régine Rein.

The Rosenchein family were originally from Czechoslovakia. Eizik (or Misik) was born on March 24, 1870 in Cinadowa. He was a tailor. His wife, Henni, was born on January 1, 1875. They had two daughters, Thérèse and Serena and lived in Ligugé. They registered themselves as Jews in Poitiers, as required by a German decree dated September 27, 1940, which obliged Jews to declare their presence in their local area and to give details of their relatives.

Eisik was arrested and transferred to the Poitiers camp on October 9, 1942 and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 42. Henni and Serena were also rounded up and deported on December 7, 1943 on Convoy 64.

b) The Salmona family

After the Rosenchein family was arrested, Paulette was placed with Esther and Moïse Salmona, who lived at 14 rue Arthur Ranc in Poitiers. Paulette must have gone to school, as her name appears on the plaque at the Victor Hugo high school in Poitiers. We have our doubts, however, as to whether Paulette, who would have been too young for high school, actually went there, especially given that it was a boys’ school.

Moïse, known as Maurice, worked in s an administrator. His wife’s maiden name was Esther Nahmias. The Salmona family, who lived in Paris before the war, had two sons: Isaac, who was born in Salonika in 1913 and Gérard, who was born in Paris in 1919 and died in Greece in 2009. The Salmona family, apart from Gérard, also registered as Jews in 1940. Moïse and Esther Salmona were deported on Convoy 66 on January 20, 1944.

5) Paulette’s return to the Poitiers camp and transfer to the UGIF children’s homes

On May 24, 1943, all the children in foster families in and around Poitiers were rounded up and taken back to the Poitiers camp. They left there on May 26, heading to Drancy camp.

There were seventy children on the bus to Paris, and they sang songs on the journey. They were not sent to Drancy in the end, but to a children’s home on rue Lamarck, which was run by the UGIF, the Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews. The UGIF was founded according to a French law passed by the Vichy government on November 29, 1941, in response to a request by the Germans during the Occupation of France. The Germans inspected the UGIF homes regularly.

a) Louveciennes

Paulette attended school in Louveciennes from October 18, 1943 to January 11, 1944. The Louveciennes children’s home was near Marly-le-Roi in the Yvelines department. She stayed at UGIF center no. 56. The Louveciennes UGIF center was a former orphanage for farmers’ children that was then converted for use as a children’s home. A Miss Schoen was the principal of the girls’ elementary school. Paulette passed the “cours préparatoire“, an elementary school certificate, when she was in the equivalent of 2nd grade, at the same time as ten other pupils, one of whom skipped a grade. During the month of October, Paulette didn’t miss a single class, but then the teacher reported that as of January 10, 1944, she had “left for another center”. Nevertheless, Paulette remained on the school roll until May 1944.

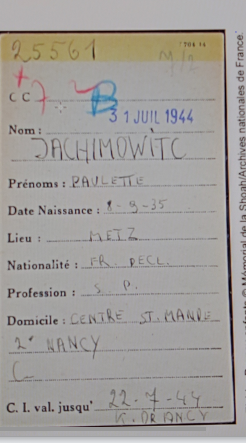

b) Saint-Mandé

The UGIF center 64, where Paulette was sent next, was at 5 rue Granville in Saint-Mandé, which is on the outskirts of Paris near the Bois de Vincennes. The home was intended for young girls in poor health. It opened in the first week of June 1943. Twelve girls were transferred there on June 1. A woman called Thérèse Cahen was in charge. The children went to Paul Bert elementary school, accompanied by Ms. Cahen. They were well looked after: the staff were very kind and there was a piano, which Ms. Cahen played. Outside school time, activities included theater, choir and sewing.

6) Paulette’s arrest and her time in Drancy

On Saturday, July 22, 1944, Aloîs Brunner organized a round-up. The little girls from Saint-Mandé, together with the staff, were taken to Drancy during the night. There they were held with all the other children from the UGIF centers in and around Paris, on stairway no.7. On July 31, 1944, they were deported on Convoy 77, the very last convoy from Drancy to Auschwitz. Ms. Cahen had promised not to abandon the children. Although she was deemed fit to work when she arrived in Auschwitz, she refused and opted to stay with them.

Out of all the girls from Saint-Mandé who were deported on this convoy, Rose Krimolowki was the only one to return alive.

We have attempted to write a monologue that Paulette might have spoken, starting on the day that she was arrested in Saint-Mandé.

“One day, on July 22, 1944, together with the other children, I left the place where I was staying, which was “the UGIF home in Saint-Mandé”. We were scared because we had to get our things together very quickly, then the German policemen told us to get on a bus. The journey took about half an hour. It was hot, and I was crying because I missed my mom so much. The manager of the home, Ms. Cahen, told me we were going to a hospitable place, and I wondered what that was. Ms. Cahen was the lady who took care of us in the home, and she was an amazing lady. She always looked out for us and helped us!

After the long journey, we finally arrived at the hospitable place, which was in fact Drancy, but I didn’t really know what it was. I saw some buildings and some people. Lots and lots of people. It was anything but the place I’d imagined. The police told us to get off the bus. I was unhappy, very unhappy. I saw lots of adults going into a sort of hut, and through the window I could see them being searched. My supervisor took us to staircase 7 and up to the second floor. I told myself that at last, I’d be reunited with my mom. I wasn’t so unhappy after that. I was with all the other children. I was hot and hungry and wanted to go to the bathroom, but the police wouldn’t let me. My mom was nowhere to be seen, so then I was sad again. I caught the smell the food coming from the kitchen downstairs. I said to myself, “At last I’m going to have something to eat”, but when we went to the dining hall, the food was terrible.

At long last, I got to use the bathroom. It smelled terrible and there wasn’t even a tap to wash your hands. I lived like that every day for nine days. I still hadn’t seen Mom and I began to think I’d never see her again…

One day, we left Drancy. They put us on buses to take us to a station, which wasn’t far away. When we got off the bus, the Germans shoved us into cattle cars. There were so many of us, we were all crammed together, it was very hot and I could no longer see daylight. The train pulled away from the platform. I wanted to get out, I needed to go to the toilet and I was hungry and thirsty. The train journey took three days. I was very scared, but Ms. Cahen was there to comfort us.

At last, the train stopped. We had arrived somewhere, but we didn’t know where. German soldiers dragged us out of the car. They shouted at us and told us to stand in line. I stayed with Ms. Cahen and the other girls from the children’s home. I didn’t understand what the Germans were saying. Ms. Cahen tried to reassure us because we were all scared. She told us everything was okay. We walked along the railroad track until we arrived in front of a German soldier, who told us to get into a truck. I was happy because I couldn’t walk any further. Ms. Cahen told us that we were finally going to be able to rest.”

Français

Français Polski

Polski