Alain JURKIEWICZ

Since we have no photo of Alain Jurkiewicz, we are showing an artist’s impression drawn by Shèmsie Ghouil, a student at the Edgar Faure junior high school in Valdahon, France.

“As they left, they had in their eyes that vestige of innocence, tainted by their anguish. Deprived of their mothers and fathers, who had vanished in the turmoil, they reached out their little hands to their executioners, never even understanding that they were victims of the barbarity of men” Albert Szerman

Introduction

We are a group of nine 9th grade students from the Edgar Faure junior high school in Valdahon. We decided to participate in the “Convoy 77” project, as suggested by our history and English teachers. The Second World War is a part of our history as moving as it is interesting. Soon there will be no more survivors, no witnesses to this dark period in history, and it seemed important to us to contribute to the duty of remembrance.

Alain Jurkiewicz, the young boy whose life we investigated, was arrested in Besançon, a town in our area. Writing his biography gave us an opportunity to pay tribute to this forgotten child, to honor his memory and to bring him back from oblivion.

It was not a straightforward task, however, as we started our research with very little information: a name, a birth certificate and a death certificate.

Our little deportee, who was of Polish origin, had a very common surname with at least three different spellings, which made our work even more difficult.

Indeed, this sometimes set us off on the wrong track, about his mother for instance, and this slowed us down a lot but made us even more curious.

Not only that, but Alain spent time in various different places, several camps and ultimately an orphanage: it proved quite difficult to put together all these pieces of information in a coherent and accurate chronological order.

Our research brought us into contact with some historians, as well as several genealogical associations, one of which led us to a particular episode during Alain’s flight to Switzerland.

In December, in the course of our research, we came across Ms. Fivaz-Silbermann’s thesis, which helped us enormously because it referred in detail to Alain Jurkiewicz’s journely through life. Then, when we were investigating the La Varenne orphanage, where Alain stayed, we had the opportunity to interact with Mr. Albert Szerman, its only surviving resident.

After hours of research and despite the coronavirus lockdown, we were we were able to retrace the steps of Alain Jurkiewicz’s short life. We are proud to share our work with you.

1. The Jurkiewicz family

Alain Jurkowitsch/Jurkiewicz (both spellings were used) was born on June 2, 1936 in Etterbeek near Brussels, in Belgium, which at the time was a separate town but is now part of the city. His parents were Szaja Modka (later renamed Maurice) Jurkowitsch, who was a hairdresser, and Ruchla Pilc, who was most likely a stay-at-home mother. He also had a sister called Rosa, who was born in Etterbeek on February 26, 1930. The family lived in a town called Forest, also in Belgium.

Three years earlier, on January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler as leader of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party, also known as the Nazi party) was appointed Chancellor of Germany. From 1935 on, starting with the Nuremberg Laws, persecutions against the Jews in Germany intensified.

Alain’s grandfather, Israel Jurkowitsch, was born in 1883 and was a Russian peddler. He arrived in Belgium in the wake of the persecution and discrimination suffered by Jews in the Russian Empire at the beginning of the century.

Szaja Modka, Alain’s father, who was born in Sulew in 1905, had four brothers and sisters. Their names were Sacha Reichel, Josephine Marie (the first of the siblings to be born in Belgium, in 1912), Daniel (who died at the age of one, in 1915), and Nathan, born in 1916.

There are no known survivors from Alain’s family.

Alain’s father, brothers, sisters and brothers and sisters-in-law were all deported to Auschwitz, as was Josephine, one of Alain’s two aunts (deported on Convoy No. 40 at the age of 30) and “Maurice”, his father (deported on Convoy No. 42 at the age of 37). Rosa, Alain’s sister, was the only one of the family to be deported from Mechelen, in Belgium, on January 15, 1943 on Transport XVIII, a convoy that included 287 children.

Despite all of our research, the fate of Alain’s mother, Ruchla, still remains an enigma. It might be that she remained hidden from the very beginning of the deportations, in 1942, as did thousands of Jews in Belgium. Alain was sent to Switzerland with his aunt in August or September 1942 and Rosa must have been moved to a hiding place. Unfortunately, she was found a short time later.

Maurice Jurkiewicz, Alain’s father

Sara Reichel Jurkiewicz, Alain’s aunt

Nathan Jurkiewicz, Alain’s uncle

Anti-Jewish persecution in Belgium

Before the Second World War, the Jewish community in Belgium numbered 100,000 people, 2,000 of whom were German Jewish refugees.

On 10 May 1940, Belgium was attacked and subsequently occupied by the Germans. The Third Reich levied the cost of the military occupation on the Belgians, through taxes. As was the case throughout Europe, food, fuel and clothing were strictly rationed by the German authorities.

From October 28, 1940 to June 1, 1942, the German authorities implemented a series of measures that gradually deprived the Jews of their rights:

➢ They were marginalized from mainstream society. A census of Jews was carried out with the aim of excluding them from the Belgian economy, isolating them from the rest of the population and preparing to deport them.

➢ As happened in France, Jewish businesses had to be identified by a publicly visible notice. Jewish businesses and shops were “aryanized” or liquidated. The Jews’ assets were confiscated. Deprived of their jobs, they were obliged to perform forced labor.

➢ On 29 August 1941, the Germans imposed a curfew on the Jews and placed them under house arrest in Brussels, Antwerp, Liege and Charleroi. They were forbidden to emigrate. They were all obliged to join the Association of Jews in Belgium, which was responsible for providing Jewish education and social assistance and facilitating their deportation. The requirement to wear the yellow star, introduced on May 27, 1942, was the symbolic culmination of the laws against the Jews. They were now in a position to be deported.

2. The flight from Belgium to Switzerland

All it took to upset little Alain’s life forever was for a taxi to take the wrong road. We shall now recount his tragic fate…

In January 1942, at the Wannsee Conference, the Nazis had resolved to exterminate the Jews of occupied Europe. Roundups proliferated throughout Europe, particularly in Belgium and France. Switzerland and the Free Zone offered the Jews one last ray of hope that they might survive.

During the night of September 16 to 17, 1942, around 4 am, four people arrived at a farm belonging to Achille and Agathe Chapatte, in a little place called Les Roussottes, near Le Cerneux Péquignot.

They were exhausted. They had probably started out from Morteau and made the 5-mile journey on foot, in the cold, through fields and woods.

The Chapattes could were unable to keep a stiff upper lip when faced with the young people’s misery and despair, and they decided to help them. On the night they arrived, they were fed, warmed up and invited to stay until the next day.

But who were these four people?

According the Swiss national archives, they were Alain Jurkiewicz, Josephine Jurkiewicz and David Chapochnik and Dwora Chapochnik (née Wajnberg).

David Chapochnik

Dwora Wajnberg

They had all fled Belgium together, when remaining in the occupied zone had become too risky. More and more Jews were being arrested, only to be deported a few weeks later. The only option for these men and women had been to leave, and they had to choose between going to the so-called “free” zone or to Switzerland.

They thus decided to leave for Switzerland, and for a good reason. They wanted to get to the Polish Consulate in Bern as quickly as possible. This would mean that they would no longer have to hide and would be able to live their lives more freely, whereas in the rest of Europe, Jews were regarded as stateless and “sub-human”.

Crossings into Switzerland usually took place at night, in order to avoid being spotted by German patrols.

As for the border crossing, let us start with the Bernard Bouveret’s account, given in an interview with France Bleu. Now 92 years old, he came originally from Chapelle-des-Bois, a small town in the Doubs department of France. He became involved in the Resistance very early on, at the age of just sixteen, initially as a courier, but then he decided to help refugees to cross the border in secret.

“In 1942, the risks were becoming greater and greater, but we were not aware of it at the time”. The five or six young resistance fighters often travelled through the woods on their way to Switzerland, forests that they knew by heart because they worked in them. “We were shot at several times”, says Bernard Bouveret. “At night, the Germans fired without warning because there was a curfew between 11:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. I recall a friend from Châtelblanc. He was killed at five o’clock in the morning, in a snowstorm, on his way back from Switzerland. The Germans put an explosive bullet in his knee. He died out there in the snow. He was 19 years old.”

But the dangers, the risks of being shot by the Gestapo, or being tortured like hundreds of other resistance fighters did not dampen the villagers’ patriotic spirit.

“It was quite easy to get Resistance fighters across the border” he recalls. “but the Jews were another matter. We moved whole families of ten or fifteen people. We carried the children on our shoulders. The people were scared. So were we. No one spoke during the journeys. The Resistance fighters feared one thing in particular: that a member of the Gestapo would infiltrate and destroy the networks. For this reason, Jews were never invited into their homes. They were scattered around in farms along the way, because these houses were close to the German border posts.”

Indeed, according to Besançon historian, François Marcot, such clandestine crossing of the demarcation line and the Swiss border was “one of the most important activities of the Resistance [in the area] due to Franche-Comté’s geo-strategic location”.

The Doubs and the Jura departments both border Switzerland, and the Jura was the only French department where the restricted zone was in direct proximity to the free zone. The historian adds: “While escape networks from north-eastern France followed a primarily urban route, the situation was quite different near the border and the demarcation line. In villages located near the line, fugitives from the northern zone found stopovers. Along the border, there were few inhabitants who had not, at one time or another, agreed to accommodate, provide for or “smuggle” those who wanted to cross the line. A whole network of accomplices can be identified, in which café and restaurant owners, railway workers and postal workers all acted as intermediaries, referring fugitives to professional “smugglers” and to small farmers who would accommodate them while they waited to cross the border. Their involvement demonstrates that, above all, there was a great sense of solidarity with victims in distress.”

In the Val-de-Morteau, Alain, his aunt Josephine and Dora and David Chapochnik also benefited from the assistance and protection of a wide network of farmers and “smugglers”, who sent the refugees to the farms that were used as assembly points.

The ancient smuggling routes had become pathways to freedom, and to hope.

The border post at Gardot

The following day, Agathe Chapatte called a cab company to take them to the Polish consulate in Bern. Fully aware of the risks she was taking, she chose to help the refugees because she feared that they would be turned back.

The cab driver, Fritz-Ulysse Zutter, who was supposed to make the trip, was unable to do so. He therefore delegated the task to his mechanic, Robert Schmidlin, who drove to Bern via the Ponts-de-Martel. If he had taken the Le Locle route, Alain might not have suffered the same fate.

At about 4 p.m., a military patrol car stopped the cab at Les Ponts-de-Martel. The driver was questioned, the passengers all had to show their identity papers and the vehicle was searched.

As they were refugees, they were taken to the border post, arrested by the German authorities and subsequently jailed in La Butte prison, in Besançon.

To read more about this in French, see this CAIRN article about Switzerland’s management of refugees, particularly between 1942 and 1944, highlighting the importance of the month of July 1944 (editor’s note SJ).

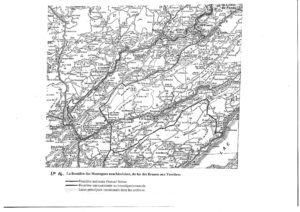

Geographical information about the area, provided by Ms Fivaz Silbermann.

The young couple and Josephine-Marie were first transferred to Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 40, on November 4, 1942. The three adults were never to return from the death camp.

As for Alain, he was sent to an orphanage at Saint-Hilaire-la-Varenne, near Paris.

What a tragic ending; the four passengers in the cab could have made it to their destination, but sadly they found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Regrettably, despite their utmost dedication and their desire to save them, the Chapattes were unsuccessful.

Following the arrest, the cab driver, the mechanic and Agathe were also arrested, but later released after being questioned by the Swiss police.

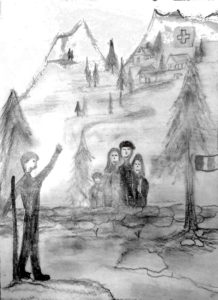

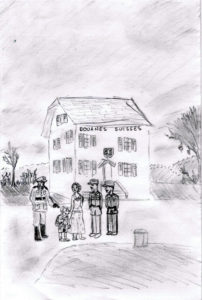

The arrest. Drawing by Robin Bollod, 9th grade student.

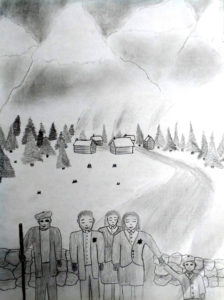

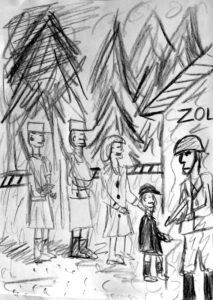

The crossing to Switzerland, as envisaged and drawn by 9th grade students.

By Mathéo Stehly

By Paolo Angelis

The border: following in the footsteps of Alain and his aunt Josephine.

A marker post on the border

A low wall, separating France and Switzerland

In the heart of a pine forest, France to the left and Switzerland to the right..

The dark, steep forests in the Doubs, at an altitude over 3000 feet

The Val de Morteau, where Alain stayed

Farms in the Jura, where Alain and Josephine found refuge just 200 feet from the Swiss border..

Farms at Cerneux Péquignot, in a place called Roussottes

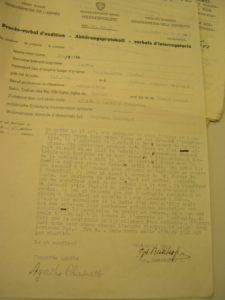

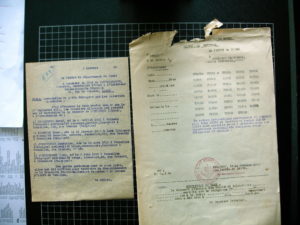

The Swiss police report.

The interrogation of Agathe Chapatte

Letter from the Head of the Police Division

Letter from the Prefect of the Doubs department, following Alain’s arrest

Drawings by Achille Combart, Téa Naveau and Justine Tisserand.

3. La Varenne: life in the orphanage

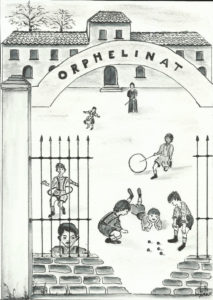

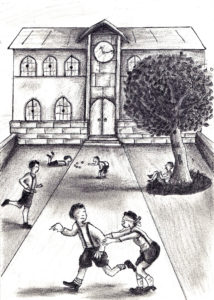

In the town of La Varenne-Saint-Hilaire, south west of Paris, there was an orphanage run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews), which took in Jewish children orphaned during the Second World War.

The orphanage housed “free” children who had often been sent there by their parents, children who had been “abandoned” for one reason or another, and children who were “blocked” or “separated”, interned by the Germans and placed in the care of the UGIF.

These so-called “blocked” children were often arrested and transferred to other facilities such as the Drancy camp. The Gestapo watched them closely and made it difficult to help them “escape”. They were at risk of being deported at any time.

During our research, we were lucky enough to have a telephone discussion with Albert Szerman, the only survivor from this orphanage. In fact, health problems on the day of the raid saved his life. In his interview, he talked about his daily life at that time, and recounted anecdotes that had an impact on him.

In the letter below he explains that he has no specific memories of Alain, but according to him, they must have played together sometimes and he compliments us on our commitment. We were very touched by his letter.

During the Second World War, life was very difficult for the population, which was deprived of various supplies.

The children in the orphanage, apart from suffering from the absence of their parents and relatives, lead a harsh life of persecution and deprivation. For example, the meals were uninteresting and repetitive, and the food was too low in calories and vitamins for growing children.

However, at least the children slept in beds with sheets and blankets every day, and such comfort was not available to everyone. Luckily the team at La Varenne was very kind, and did everything possible to make sure the children were as well cared for as possible. The monitors were lovely and taught the children songs, played with them, and even took them for walks. However, the children do not go to school and most were unable to read and write. For this reason, Albert Szerman only learned to read at the age of 9, after the war ended.

There was even an infirmary in La Varenne, which provided some relief if the children were sick.

To conclude, La Varenne was an orphanage in which the children managed to be happy at times, despite everything, and found some stability. Some of them, at such a young age, no longer remembered their parents, but they were shown a great deal of affection by their caregivers such as Roberte Caraco, Raphaëlle Chetblum and Olga Kahn.

Sadly, however, Alain Jurkiewicz could not escape the roundup that led to the entire orphanage being taken to Auschwitz.

The orphanage, as envisaged and drawn by 9th grade students

4. The arrest at the orphanage at La Varenne

In July 1944, the Normandy front was breached. As the Allies moved closer to Paris, the Nazis increased the number of deportation convoys.

In July 1944, the Normandy front was breached. As the Allies moved closer to Paris, the Nazis increased the number of deportation convoys.

A few days before the raid on La Varenne, some children left the orphanage at night with Resistance members. Alain was not among them because he was stranded, or “blocked”.

He had already been arrested by the Gestapo and thus was not allowed to leave the orphanage.

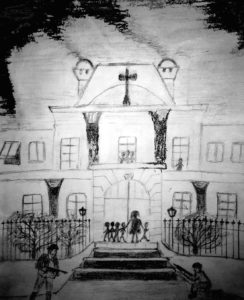

On the evening of July 23, 1944, the children, who ranged in age from 4 to 11, were brutally awakened by screams and knocks on the door of the orphanage. The caregivers tried to calm them down. The children were afraid, and did not want to leave as instructed by the SS who were shooting at the facade of the orphanage.

Albert Szerman, who was 8 years old at the time, was ill when this happened, and he watched the scene from the window of the infirmary: “The orphanage was surrounded in the middle of the night and the SS ordered it to be evacuated, but the children, overcome by panic, refused to come down. So, the SS, to show their determination, began firing automatic weapons at the facade of the orphanage (…) Eighteen frightened children came out. They were put on a bus, along with five female staff members. However, one of them convinced the Germans that she was not Jewish. She was allowed to leave.”

The caregivers were deported along with the children.

Drawing by Juliette Mougey.

Drawing by Noémie Dubo: Albert Szerman standing in front of the wall riddled with bullet holes, in the early hours of the morning

Photograph: The orphanage on rue Saint-Hilaire in La Varenne. Exact date unknown, but between June 1942 and July 1944.

Source: Groupe Saint-Maurien contre l’oubli. Les orphelins de La Varenne 1941-1944, Le Vieux Saint Maur Editeur, 1995, p.118

5. Drancy and the deportation: witness accounts

The children rounded-up in La Varenne, along with some from other homes, were taken to the Drancy camp. Another internee, André Warlin, recounts the children’s arrival and stay in the camp in his book, L’Impossible Oubli:

“On a clear, starry night, we could hear the noise of the buses coming and going, one after another […] We did not see the newcomers right away. But soon, to our indescribable horror, we heard the sparkling, jabbering voices of small children, alone, fatherless and motherless. There were some toddlers as young as two years old dragging their miserable bundles around. They were crying. They’d had no time to get dressed. They’d been dragged out of their beds and tossed around. […]

They were just left on empty landings, people improvising diapers for them and squeezing them together into beds infested with bedbugs. The whole camp was in turmoil. […]

The following day, disciplined, well-behaved, accustomed to obeying and suffering, they all lined up in the refectory, holding oversized bowls in their tiny hands and playing with their spoons. The five-year-olds took care of the toddlers. They were mature for their age and knew how to adapt. They had experienced life, persecution, and suffering, separated from their parents. […] They knew that they were Jewish: it was often the only thing they did know, not even knowing even their own name. They knew that they were in danger, having heard about the camps and deportation ever since they were born. As little children, they had an instinct for self-preservation, as do young animals. They tried to flee from danger. One of them was found in the dog’s kennel. “I want to be a dog,” he said, “because dogs don’t get deported.” […]

Then one fine day, we watched them leave.

The Allies had not advanced fast enough. The miracle did not happen.”

On July 31, 1944, Alain, his friends and caregivers were all deported from Drancy to Auschwitz. We know a few details about this horrific journey thanks to survivors’ testimonies. Here are two of them:

The journey was appalling, with the detainees crammed into cattle cars. Suzanne remembers the lack of air, the thirst, the difficulties encountered by the elderly, the air of madness, the straw on the ground, the smell and the promiscuity. A simple bucket and a sheet served as a lavatory for the entire wagon. The train stopped occasionally to empty the buckets and some people tried to take advantage of the opportunity to escape.

On arrival in Auschwitz, there was a long wait in the cattle car, over three hours with no way out, waiting for the previous wagons to be emptied. The doors opened. It was night time. Children were screaming, and mothers too, while the Kapos were shouting and their fearsome dogs were barking. Suzanne was petrified and as she jumped out of the wagon her feet slipped from under her. Fortunately, her friend Jeanine, along with some others, pulled her up and gave her friend the courage to continue. Almost immediately, a doctor, the infamous Mengele, made a “selection” with his stick: to the right, those who could work; to the left, everyone else. Suzanne was sent to the right. Mengele tapped her on the shoulder and said, chillingly, “Next time”. Suzanne then went through all the stages of dehumanization: getting undressed as a group in the Sauna [disinfection area], having her head shaved under duress and getting a tattoo (which she had removed when she returned to France).

Suzanne Barman (married name Boukobza)

“On July 31, 1944, we had to leave the camp. We were sent to a small train station where cattle cars were waiting for us. Supplies, buckets, mattresses, 48 kids and 12 adults were all crammed in. The wagons were locked, the convoy shook and we were 1300 people heading for the unknown. In the evening when the children had to go to bed in the dark, the screams began: impossible to sleep, it was hot, they were thirsty, the air was starting to run out. That same evening we crossed the Rhine.

It was the third night and the children were asleep. The train came to a halt. Germans were shouting “Schnell, Schnell Raus”. Shaven-headed men, their eyes haggard, dragged everyone abruptly onto the platform. I spoke to one of them: “Get back on the train, I can’t talk to you here” he said. He was a Frenchman. And most importantly, he told me, “don’t hold any kids in your arms!” But why? “You’ll understand in a few days’ time. The little ones, you see, they are going to be made into soap”. I saw a little girl all alone on the platform. I didn’t have the courage to leave her, so I took her by the hand. The man came up to us and said in a firm voice, “You haven’t understood what I’ve just told you …”. I left the little girl in the middle of a group of children and continued on alone. It was pitch dark, a German barricade in the middle of the road, spotlights pointed right at us: “Go right”, “Go left”, there was yelling from all directions. I found myself with 170 young and able-bodied people, the others got into the trucks. Those who had just been separated from a husband, or a young child, were sobbing”.

Denise Holstein

Conclusion

Alain Jurkiewicz was most likely murdered in the gas chambers on the night of August 4-5, 1944, along with many other innocent victims of Nazi barbarism and fanaticism.

This humble contribution has given us the opportunity to pay tribute to Alain and, most importantly, never to forget that almost 76 years ago, innocent children were massacred in the name of an ideology.

Our research about his mother was less successful, and some questions remain unanswered: Might she have survived the genocide under a different name? Why was Alain with his aunt, rather than with his mother?

This project has taught us how to carry out in-depth research and how to work as a team on a collaborative project. We had to untangle the facts from the fiction at each stage and we learned to be patient throughout the difficult but fascinating research process.

Alain, together with his friends from the orphanage, has now become a part of our lives as high school students and will remain with us in the future.

We must never forget.

We would like to thank the people who helped us during our research: Stéphane Amelineau, documentary professor at Château Thierry and friend of Albert Szerman, sole survivor of the orphanage of La Varenne, Micheline Gutmann of the association Genami, and Ruth Fivaz-Silbermann author of the thesis: La fuite en Suisse : migrations, stratégies, fuite, accueil, refoulement et destin des réfugiés juifs venus de France durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale (The flight to Switzerland: migrations, strategies, escape, reception, rejection and fate of Jewish refugees from France during the Second World War.)

Bibliography

FIVAZ-SILBERMANN RUTH, La fuite en Suisse. Migrations, stratégies, fuite, accueil, refoulement et destin des réfugiés juifs venus de France durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Thèse de doctorat Université de Genève, 2017

GROUPE SAINT-MAURINE CONTRE L’OUBLI, Les orphelins de la Varenne 1941-1944, L’Harmattan, 2004

MARCOT FRANCOIS, La résistance dans le Jura/ La Franche-Comté sous l’occupation, Cêtre, 1992

MARCOT FRANCOIS, Résistance et population( 1940-1944), Université de Franche-Comté, 1994

VUILLET BERNARD, Le Val de Morteau sous l’occupation, Archives et témoignages, 2005

Contributor(s)

This biography was researched and written by nine 9th grade students from the Edgar Faure Junior High school in Valdahon, with the guidance of their history and English teachers, Mr. Dupré and Ms. Falempe. The students were Enzo Beckert, Alexandre Boucher, Maël Guillot, Léola Jeandenand, Meltem Kurt, Manon Lenoble, Gratianne Loriod, Quentin Morel and Lydie Vuillemin. All of the 9th grade classes at the school were involved in making the drawings.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Chers enseignants et élèves, nous avons reçu un message de Belgique, de la part d’une chercheuse faisant des recherches sur les monuments funéraires. Kathleen LEYS nous indique :

Le site mentionne ‘Malgré toutes nos recherches le destin de la maman d’Alain, Ruchla reste encore une énigme pour nous. On peut penser aussi qu’elle était cachée en 1942, dès le début de la grande déportation, comme des milliers de juifs en Belgique.’

Je pense que la mère d’Alain est enterrée – ou a un monument funéraire – à Dilbeek (voir photo). Prénom: Lea. Grand-mère: Rachla (Gutermann)???

Je continue mes recherches afin d’écrire un texte autour de cette histoire (en néerlandais) et j’espère que ces informations pourront vous aider à combler les éléments manquants.