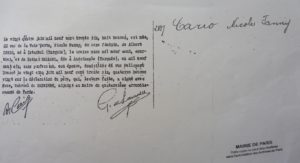

Albert Cario

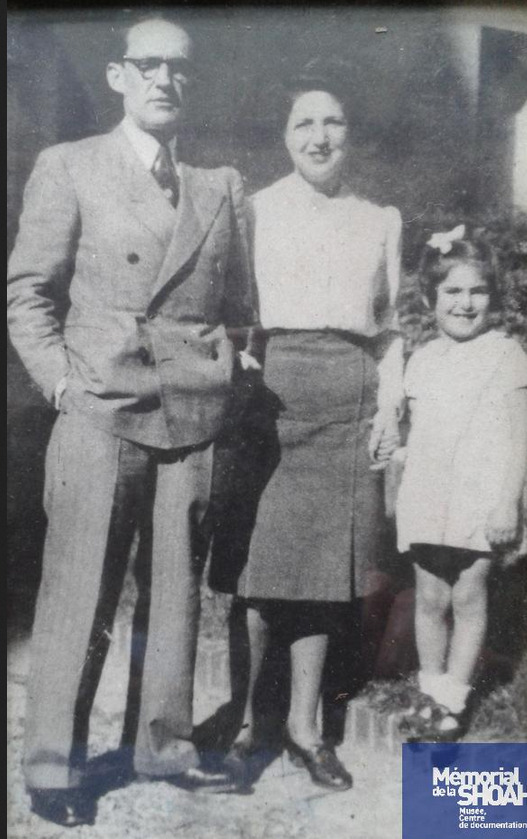

Photograph source: Shoah Memorial, Paris – Laurence Cohen-Carraud collection

“The distinction between our family histories and what we call History, with its pompous capital letter, makes no sense. They are exactly the same thing. There is not, on one side, the great and good of this world, with their scepters and televised speeches, and on the other side, the drudgery of daily life, the short-lived anger and hope, the anonymous tears and unknown people whose names are rusting away at the foot of a war memorial or in some country cemetery.” Ivan Jablonka, in “A History of the Grandparents I never had”.

To begin with, the students worked on this passage and thought about the ways in which family stories shape History, because I had been so impressed by the book. I had no idea that the Jablonka family knew one of Régine Balloul’s daughters, a sister of Esther Cario, Albert Cario’s wife. We only discovered this at the end of the project.

Here is the students’ work, in their own words:

In order to read the documents in the biography more clearly, click on the images to see them in their original format.

A man who lived in our neighborhood

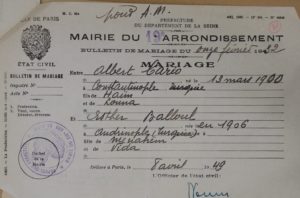

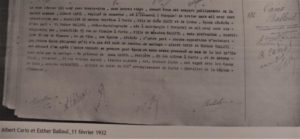

The first record is Albert Cario and Esther Balloul’s marriage certificate, which is dated February 11, 1932, but was only issued on April 8, 1949 by the town hall of the 19th district of Paris.

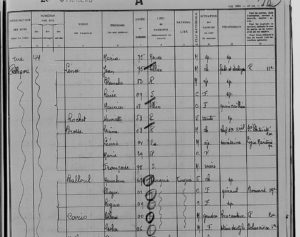

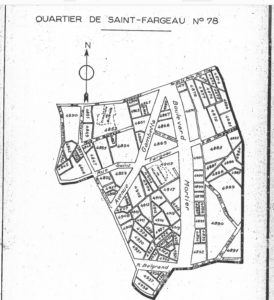

The second record is the 1936 census of the population of the Saint-Fargeau district of Paris.

From the first record we discovered that Albert was born on March 13, 1900 in Constantinople, Turkey and that his parents were called Haïm and Louna Cario, that Esther was born in 1906 in Andrinople, Turkey and that her parents were Menahem and Vida Balloul and that Albert and Esther were married on February 11, 1932 in the 19th district of Paris. At that time, Turkey was part of the Ottoman Empire.

From the second record (an extract from the 1936 census, found in the Paris Archives) we discovered that the Esther and Albert Cario lived with the Balloul family (Esther’s father and two of his children) at 44 rue de Pelleport in the 20th district of Paris. Esther’s father was the head of the household. He was unemployed, as was one of his children, Régine. His other child, Eliezer, was the manager of a store in the 19th district of Paris, while Albert was a secondhand dealer in the 20th district and his wife, Esther, was a typist.

The census data shows that everyone in the Balloul/Cario household was born in Turkey. Menahem was the head of the household and Albert was his son-in-law. Menahem was a widower, Albert and Esther were married and both Eliezer and Regine were single.

We also see that Eliezer’s employer was a firm called Bernard, in the 19th district, that Albert had his own business and that Esther worked for a firm called Delavaivre, in the 1st district of Paris.

44 rue Pelleport today:

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

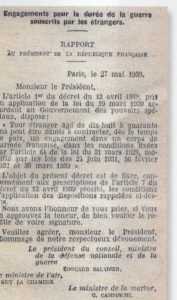

A soldier during the Second World War

Albert Cario was born on March 13, 1900 in Constantinople. He was a Turkish immigrant who voluntarily enlisted in the French army in 1939 (service number 16239). He was allowed to do so according to a law dated May 27, 1939, but he only just made it, since he was 39 years old at the time and the maximum age allowed was 40. He had no criminal record. His unit was based at train depot n° 9 in the first military division and he enlisted at the Seine department central recruitment office.

Dossier 8_0087 Enlistment records.

The Shoah Memorial in Paris runs a workshop entitled “In the Name of Freedom”, in which the students took part.

They focused on the lives of other people who had volunteered in the same way as Albert Cario: Léo Cohn (who joined the First Foreign Infantry Regiment), Joseph Kessel (who joined the Free French Air Force), Joseph Epstein (leader of the Franc-Tireurs et Partisans guerrilla fighters in Paris) and Victor Fajnzylberg (who joined the International Brigade).

In September 1939, foreigners began to volunteer for the army. Of the 83,000 who applied, 43,000 were recruited, 25,000 of whom were Jews. The volunteers wanted to defend their adopted country from the Nazi aggression, to work together with the French soldiers and to become French citizens. In doing so, they risked their lives. More than 25,000 Jewish volunteers were drafted into the infantry regiments of foreign volunteers (RMVE), the Foreign Legion and the Polish and Czechoslovakian armies operating in France.

Only some of the volunteers were actually mobilized over the winter of 1939 and in the spring of 1940, depending on requirements, the equipment available, which was often lacking, and the capacity of the army in question.

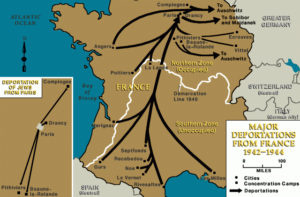

The context in which Albert Cario was arrested and deported

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

In 1944, France was divided in two. The free zone, in the south, was ruled by Marshal Pétain, who had been in power since 1940, and the occupied zone in the north, which had been taken over by Nazi Germany, also in 1940.

The Russian army’s victories over the German army in Europe (including Stalingrad on February 2, 1943) enabled it to conquer and/or recapture a number of areas, particularly on the Eastern front, including in Finland, Romania and Bulgaria, where the Germans retreated. Moreover, on the Western Front, the conquest of Italy (one of the three Axis countries, together with Japan and Germany) began in January 1944.

The Eastern Front: In the summer of 1944, the Russians launched a major offensive, which liberated the remainder of Belarus and Ukraine, the Baltic states, and eastern Poland from Nazi domination. In August 1944, the Soviet troops crossed the German border.

Nazi Germany began to lose more and more battles to the USSR and on June 6, 1944, the Americans, British, Canadians and some French resistance fighters led by General de Gaulle landed in Normandy. Faced with successive military defeats, Hitler ordered the German troops to deport and kill more Jews.

This was the context in which Convoy 77, one of the last large convoys from France, was organized. It left Drancy for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, carrying more than a thousand Jews.

The German troops in France became even more focused on their task, aware that there were only a short time left before the Allies reached Paris. This proved to be true, since Paris was liberated on August 26, 1944.

Albert Cario was arrested and deported about a month after the Allied landings in Normandy and a month before Paris was liberated. This marked the end of the Vichy regime (which was replaced by the CFLN, the French Committee for National Liberation, which became the new government) and the last council of ministers in Vichy was held on July 12, 1944. For the German army, it was a debacle. France was liberated little by little thanks to the Allies.

Internment in Drancy camp

A cattle car at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy.

A cattle car at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy.

“One story particularly struck me: the one in which one of the former internees recalled that when he was playing on a balcony with some other children, a German soldier shouted loudly and pointed his gun at them. This episode attests to the brutality of life in the camp and the cruelty of the guards.”

“The children were treated the same as the adults. The majority of the guards had no mercy toward them and even went as far as hitting them.”

“Another thing that made an impression on me were the drawings made by the internees: dark, sad and gloomy, they depict life in the camp. This bleak and dismal way of depicting what they saw shows their despair at being interned in the camp, as shown by the titles of these drawings, “Living like a dog” and “On the threshold of hell” in particular.”

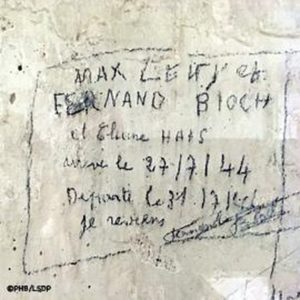

“I also saw the remains of a wall on which is engraved a name, the date of arrival and deportation and a phrase that moved me immensely, which is “I will be back”.”

Eliane Haas were deported on Convoy 77

“What moved me the most was the story of the tunnel built by the internees to escape and then discovered by the guards. Luckily, the 12 internees who were caught were sent to another camp. On the train, they managed to escape along with the other people in the car.”

https://www.fondationshoah.org/memoire/les-evades-de-drancy-de-nicolas-levy-beff

“The hunger and the incessant noise seemed to come up again and again in the testimonies; it must have been really traumatic for them. The sanitary conditions were appalling and I can’t understand how people enjoyed making other people suffer like that. One thing that came up a lot in the testimonies, even though the camp survivors who were interviewed were not asked about it, was the fact that they did not want to be noticed because of the risk of being hurt. The example given of how important it was to respect this unwritten rule is quite simply horrifying and chilling: turning a gun on children because they were playing noisily is appalling.”

“One thing that really amazed me was that people (police officers and their families) voluntarily agreed to live in the towers overlooking the camp and thus were able to watch men, women and children suffering all day long. These people were despicable.”

“What impressed me the most during our visit to Drancy was the railroad car. This SNCF wagon was used to deport Jews to Auschwitz to be slaughtered like cattle.”

“What struck me during the visit to the Drancy Memorial and listening to the testimonies was the lack of hygiene. Knowing that people slept on the floor on mats full of excrement and that they could not wash themselves at the taps with even a little privacy shocked me. Also what struck me during this visit and listening to testimonies was the how hungry these people were in the camps. Parents would sacrifice themselves so that their children could eat and not go hungry by giving them their own food. The little boys rummaging through the garbage looking for leftovers and eating whatever they could really made my heart ache. No one deserves to be that hungry and everyone should have enough to eat. Life in the camps was monstrous for everyone and I think even more so for those who were there without their parents.”

“The fact of seeing the enormous number of children who were interned really struck me; it seemed unthinkable and senseless to me to see so many children living in such conditions, most of them without their mothers and for reasons that were completely incomprehensible at their age. No one deserves to live in such poor living and sanitary conditions no matter who they are, regardless of their background, religion or sexual orientation. These children deserved nothing of what they went through.”

“During the visit to the Drancy Memorial, the thing that struck me most was the children who must have been left with no points of reference, no parents and no brothers and sisters. And when, during their testimony, one of them said that because their soup was not enough for them, they waited for the cooks to take out the garbage so that they could eat whatever they could find. Because they were very hungry, and that made me react immediately because I find it sad that a child could not eat as much as he or she wanted.”

His arrest and deportation

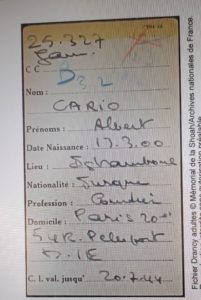

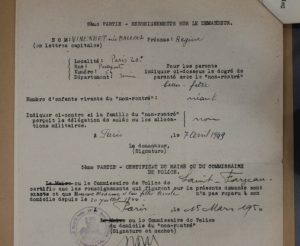

Drancy internment record

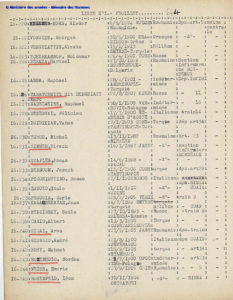

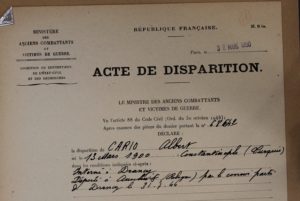

Albert Cario was officially registered as having disappeared on March 30, 1950. He was arrested on July 20, 1944, interned in Drancy and deported on July 31, 1944 to Auschwitz, in Poland.

Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service.

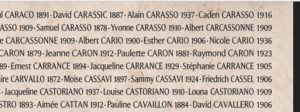

On the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris we were able to see the names of Albert, Esther and Nicole Cario:

Research undertaken by relatives; the students investigate

Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service

Records show that victims’ relatives applied to have them officially acknowledged as “non-returnees”, meaning that they never back after having been deported. In this case, it was Régine Vinerbet, since in the section “for relatives, note below your relationship with the “non-returned person””, she stated for Albert that it was her brother-in-law.

Based on the Cario family records, we can see that Régine Vinerbet, Albert Cario’s sister-in-law, filed an application to the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War on March 15, 1950, in order to have Nicole, Albert and Esther Cario’s recognized as non-returnees.

Their closest family members, such as Régine Vinerbet, were concerned about them and made inquiries to find out what had happened to them. To do this, she made a “non-returned person” declaration by submitting the necessary paperwork to the Saint Fargeau Police Department in Paris.

From the records that we have , it is impossible to tell if her request was granted. It is clear that they died, but Régine wanted to know where and in what circumstances. We noticed, however, that she had the same address as the Cario family (54 rue Pelleport, postcode 75020), so might she have lived with them?

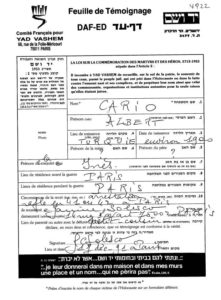

According to the testimony sheets recorded and made available by the French committee of Yad Vashem, it was a Janine Solesco who undertook to have the Cario family listed as Holocaust victims.

This person was living at 14 rue Favart in the 2nd district of Paris.

The Poccard restaurant on rue Favart.

https://www.lesnocesdejeannette.com/restaurants-insolites-paris

https://www.lessoireesdeparis.com/2018/11/28/les-roses-de-poccardi/

Perhaps we could contact her by mail, we thought, and perhaps she might have some other records or information. A branch of Esther’s or Albert’s family lived in the 2nd district of Paris: perhaps they still do?

Either way, the address given on December 17, 1991, which was 14 rue Favart, postcode 75002, now seems to be that of a restaurant called Les Noces de Jeannette, formerly the Poccardi.

At the Bibliothèque historique des postes et télécommunications (Historical Library of Post and Telecommunications) on rue Pelleport, a search of the microfilms of old directories revealed that Janine Solesco had lived in the 12th district. However, when we went to the address given, no one was able to give us her current address.

Microfilms at the Historical Library of Post and Telecommunications

Microfilms at the Historical Library of Post and Telecommunications

On the page on the Shoah Memorial website we noticed that at the bottom it says Coll. Laurence Cohen-Carraud. We therefore searched for what Coll means. It apparently means collaborator, in particular if someone has helped to provide an image or document. We wondered if the photo of the Cario family belonged to Laurence Cohen-Carraud, and we then tried to find out more about her: 5.

https://www.annuairetel247.com/cohen-carraud-laurence-paris-rue-dareau

Perhaps this was the person mentioned below the photo?

We got in touch with her.

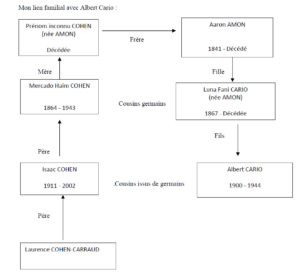

She sent us Albert’s family tree:

Laurence Cohen-Carraud is a distant cousin of the Amon family: Albert Cario’s mother was Fanny Louna, née Amon. Laurence Cohen-Carraud says:

“A long time ago, my father, Isaac Cohen, recognized Leon Cario and a cousin, Henri Amon, in a photo, but said nothing else. Our family was also severely affected by deportation (convoys 59 and 63: my grandparents Mercado, Sultana, my uncles Joseph and Jacques, my aunt Marie, my cousin Monique and two of my grandparents’ cousins including Rebecca Amon-Chaki, Fanny Louna Amon-Cario’s sister)

6.https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=fulltext%3A%28MERCADO%20COHEN%29%20AND%20id_pers%3A%28%2A%29&spec_expand=1&start=0

and it was impossible to talk about it with Papa, or to ask him even the tiniest question, because it would lead to floods of tears. We thus became accustomed to not asking questions.

Later on, I did some genealogical research and I think that we are related to the Amon family through my great-grandmother ( my grandfather Mercado Cohen’s mother), who was probably Aaron Amon’s sister, Louna Amon’s father and Albert Cario’s grandfather. This has been corroborated by a DNA test taken by my first cousin Claude Cohen as well as by Moris Amon ( the son of Emil Amon, grandson of Vitali Haïm Amon, showing that they are fourth cousins).

I was also able to find, thanks to a photo found on the Museum of Jewish Art and History website, Henri Amon’s daughter, Monique Thibault-Amon. She put me in contact with some other descendants of the Amon-Cario family via the My Heritage genealogy site. As a result, I was able to contact Julio in Costa Rica, the grandson of Albert Cario’s sister Victoria, and Peter in Australia and Mark in the United States, both grandsons of Albert Cario’s brother Maurice. Their cousin Moris in the States also gave me some information. From their stories, along with those of my cousins Claude and Françoise, and my own research in archives, I was able to piece together the following information about Albert Cario’s family.

Their genealogical research goes back as far as Albert Cario’s grandparents: Aaron Amon and Susana Sultana Salti, who were married in around 1858.

They had five children, including Fanny Louna Amon, Albert Cario’s mother. Fanny Louna’s siblings are: Yom Tov Amon, Vitali Haïm Amon, Rébecca Amon (married name Chaki) and Menahem Amon.

It should be noted that the spellings of names may differ from document to document: Indeed, the spelling of names/first names must be treated with caution, because in the 19th century and early 20th century, names were written either in Hebrew, or in Judeo-Spanish using the Rashi or Solitrao alphabets, or in Turkish using the Muslim alphabet. As a result, they were transcribed into French phonetically, so we find, for example, the following:

- Susana/Suzanne/Suzanna (often associated with Sultana)

- Haïm, Hayim, Haym, (meaning life, often associated with Vitali)

- Fanny Louna/Fannie Luna/Fani Luna

Also, sometimes names that were regarded as too Jewish or too different were changed completely into French names: Thus, as Leon Cario told his grand-nephew Julio, Albert replaced Abraham, Maurice/Morris replaced Moses or Mordechai, Arthur replaced Aaron and Leon replaced Jehuda.

Albert’s family:

Fanny Louna Amon married Vitali Haïm (or Hayim or Chaim) Cario. Vitali was a banker.

They had had six children, five girls and a boy, called Maurice, Arthur, Albert, Victoria, Léon and Joseph.

They lived in Constantinople, I think on the Asian side, in Kuzguncuk.

Their eldest son, Maurice, began studying medicine in Paris, probably shortly before the First World War. His brother Arthur was in England during the First World War and was interned in a prison camp, because Turkey was hostile to England at the time. Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire were sometimes considered enemies of the Triple Entente, but also sometimes held a special, protected status, as they were not legally considered as Turkish citizens. In France, as well as in England, members of the family found themselves in both of these situations.

Fanny Louna and her husband, Vitali Haïm Cario, died of typhoid fever in Turkey around this time. Their youngest children were temporarily adopted by their maternal uncles Vitali Haïm Amon and Menachem Amon.

It was the 1920s, when Victoria, Albert, Léon and Joseph travelled to France to be with Maurice.

Albert’s siblings:

Maurice Cario

Maurice Cario gave up studying medicine after his fourth year at the Sorbonne in Paris in order to learn about the diamond trade. One of his brothers was already working in this sector. When he finished his training, he was sent to Hong Kong, probably in the early 1920s, to work in the precious stone business. He lived there for the rest of his life, except for a spell (perhaps a year?) in Japan in the 1930s to buy pearls from the emerging cultured pearl industry.

At some point in the 1920s or 1930s, he secured a seat in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and began working part-time as a broker. He was a founding member of the Hong Kong Stockbrokers’ Association. During the Second World War, his business was plundered by the Japanese and he was interned. He gave up the gemstone industry after the war and concentrated on his stock market trading. He sold his seat in the stock market and retired in the 1970s. He moved to the United States to live with his daughter and grandchildren in Annandale, Virginia, in the early 1980s and died on April 5, 1983 at his home in Annandale.

Maurice and Laura on their wedding day

Maurice and Laura on their wedding day

Arthur Cario

Albert Cario’s second brother was born in Constantinople on November 24, 1895. According to Julio, Arthur Cario lived in England during the First World War and was interned in a prison camp as an “enemy alien”. He was a pearl broker, who lived at 7 rue Cadet in Paris. He remained single and died in his home on January 29, 1924.

Albert Cario

Albert Cario was therefore the third of the siblings. He was born on March 13, 1900 in Constantinople, and when he married Esther Balloul, he was a sales person and was living at 18 avenue Secrétan in Paris.

It is interesting to note that none of Albert’s or Esther’s family members were witnesses at their wedding. As far as Albert was concerned, Maurice and Victoria had already left France and Arthur had died 8 years earlier. Léon and Joseph still lived in Paris, however.

Their daughter Nicole Fanny was born on June 24, 1936 in the 14th district of Paris, at 22 rue de la Voie Verte. They lived at 44 rue Pelleport in Paris. Albert was a broker at the time. We note that Nicole’s middle name was Fanny, her paternal grandmother’s name. Her father Albert Cario’s signature is also visible on her birth certificate.

Although he had volunteered to serve in the war as a foreigner at the Seine Recruitment Office in 1939, despite his age and family responsibilities, he was arrested on July 20, 1944 along with his wife Esther and their daughter Nicole.

They were interned in Drancy camp and deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 on Convoy 77.

Victoria Cario (married name Amon)

Albert Cario’s sister, Victoria Cario, was born in 1904 in Constantinople and died in San José, Costa Rica, on July 25, 1971.

Victoria married her mother’s cousin, Isaac Amon-Betsallel, whose family had also emigrated to France after World War II. After they were married in about 1923 in Lyon, France, they emigrated first to Curaçao and then to Costa Rica. Their grandson, Julio, says:

“My grandfather was already living in Costa Rica. His business depended a lot on his brother Raphael (who was deported in 1942 on Convoy No. 3) who sent him goods from France such as linen, cashmere, Marseille soap, wine, olive oil, etc. He also sold some Chinese products, which came from Hong Kong. Peter’s grandfather, Maurice Cario, who lived there, helped him to make business connections.”

Victoria Cario-Amon with her son Alberto Amon-Cario. (Curaçao 1926). Photo kindly provided by Julio, Victoria’s grandson.

Léon Cario

Léon was born on July 10, 1905 in Constantinople.

He arrived in France in 1925. We suppose therefore that Albert and Joseph did too.

He first lived at 31 rue de Maubeuge in Paris and was a jewelry broker at 11 bis rue de Maubeuge. In November 1932, he went to live with his aunt (widowed name Abeniacar) at 8 bis Boulevard d’Ormesson in Enghien-les-Bains in the Val-d’Oise department of France.

Léon Cario with my uncles Joseph and David Cohen in about 1938 – Photo kindly provided by my cousin Françoise.

Monique told me that her father, Henri Amon, was a first cousin of Léon Cario. Léon visited Henri three times a week. He would eat “pishcado” (fish) on Friday evenings at their house. My cousin Françoise told me that he went to my uncle David’s house on Sundays. Léon was probably a stateless person during the war.

He never had a store, although he was a diamond dealer. He was a diamond dealer. He was always at the Club des Diamantaires on rue Cadet. He remained single and never had any children.

Léon was a very secretive man. Monique never went to his house and did not even know where he lived.

Photo taken in 1947, with Monique Amon and Françoise (David Cohen’s daughter) as children. Photo kindly provided by Monique.

He never really recovered after his brother Albert and his family were deported.

He died on February 1, 1994 in Garches, in western Paris.

Joseph Cario

Joseph was the youngest of the siblings: He was born on January 8, 1908 in Constantinople.

Joseph was naturalized as a French citizen on April 15, 1930. He changed his first name to José Pierre.

A watchmaker and jeweler by trade, he lived at 92 rue de Montreuil in Vincennes.

He also never recovered after his brother Albert and his family were deported.

He died of cancer in Paris on September 28, 1953.

We don’t have any photos of him.

I don’t know if it was at his house or at Albert’s that Papa took refuge that first night after his family was arrested in 1943. Papa only ever said in a letter that he spent that terrible night with Léon Cario’s brother.

I asked the Amon Carlo family if they had any souvenirs or memories of Albert.

Julio Fernandez, grandson of Victoria Cario, sister of Albert Cario, who went to live in Costa Rica in the 1920s, sent me this photo with a note saying: “After the war, Uncle Leon met Albert’s housekeeper who told him that the French had taken all his belongings from his apartment but had left behind these opera glasses, which she gave to him and which Leon then passed on to my grandmother, Victoria.

And that brings Laurence Cohen-Carraud’s story to a close.

It was through a daughter of Régine Vinerbet, née Balloul, that we discovered the story of how the Cario family was arrested: Albert and Inès wanted to stay in Paris, thinking they would be shielded by their Turkish citizenship. They sent Nicole to live with Régine Balloul in Saint-Solve in the Correze department for a year or so. Nicole then returned to Paris and her parents had to hide somewhere other than at 54 rue Pelleport. Nevertheless, so that she could continue to go to school, Nicole must have gone to a neighbor’s house at lunchtime.

Régine Balloul said that Nicole was most likely reported. She was arrested first, and as a result, her parents were arrested too. Nicole, Albert and Inés were all deported and gassed as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

To conclude this biography, a few final comments: “The Convoy 77 project moved us deeply because the Cario family’s story is so very sad. It enabled us to discover the cruelty that Jewish people suffered during the war. What happened to them was inhumane and we were shocked and upset by it.” “We shared in their experiences and feelings through the archived records”. “Even though Albert Cario was not born French, he volunteered in the French army and fought in it but still he and his family were deported”.

Sources:

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service.

- Yad Vashem website

- The Universal Israelite Alliance library

- Encyclopedia United State Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Paris City archives

- Historical Library of Post and Telecommunications

Links :

- https://www.fondationshoah.org/memoire/les-evades-de-drancy-de-nicolas-levy-beff

- https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en&s_id=&s_lastName=cario&s_firstName=IN%C3%A8s&s_place=&s_dateOfBirth=&cluster=true

- https://www.lesnocesdejeannette.com/restaurants-insolites-paris,

- https://www.lessoireesdeparis.com/2018/11/28/les-roses-de-poccardi/

- https://www.annuairetel247.com/cohen-carraud-laurence-paris-rue-dareau

- https://www.bibliotheque-numerique-aiu.org/tous/item/9176-photo-de-groupe-l-alliance-a-casablanca

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Thank you so very much for all of your work. This appears to be the best documented history of my family I have ever seen. I had heard parts of the story, but my grandfather, Maurice Cario, did not speak much of his family. He just said that Albert and his family had died. Reading all this and seeing the documents for the first time was extremely moving and difficult. It’s a very impressive piece of scholarship by young people. I’m very grateful.