Camille MEYER

Resistance to deportation in France and in Europe

2023-2024 round of the French National Resistance and Deportation Contest.

Prosopographical research: some biographical details about the lives of Camille Meyer and Daniel Naiman, who were deported on Convoy 77.

In his book Le Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Jews deported from France [1], Serge Klarsfeld wrote of Convoy No 77: “The number of deportees was 1,300. Convoy 77 (…) carried more than 300 children under the age of 18 to the gas chambers in Auschwitz. (…) 291 men were selected with registration numbers B 3673 to B 3963, as were 283 women (A 16457 to A 16739). By 1945, there were 209 survivors, 141 of them women.

“I will give them an everlasting name” (Isaiah 56.5, Bible KJV

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The Convoy 77 European project

- The UGIF

- The roundup on rue Vauquelin

- Daniel Naiman

- Annex

- Bibliography

Opening remarks

In researching the lives of Camille Meyer and Daniel Naiman, both of whom were deported on Convoy 77, we found a great deal of information about Mr. Naiman’s life. Details about Ms. Meyer’s life, on the other hand, are few and far between, but our research has enabled us to sketch a broad outline of her life nevertheless.

We requested some information on arolsen.org: the Arolsen Archives sent us some records about Mr. Naiman, but they have nothing on Ms. Camille Meyer née Belaich. On other research sites, we found only snippets of information about her.

As we attempt to keep the memory of Camille Meyer and Daniel Naiman alive, it is important to bear in mind that our work was carried out as part of the Convoy 77 European project. We must also remember the reason Ms. Meyer was staying in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, and the roundup that took place there.

Introduction

The two biographies we have written are both about French deportees. They were written as a contribution to the work of the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, a European project which aims to document the lives of all of the people who were deported on this particular convoy

To survive is also to resist. There are many different types of resistance, and not everyone resists in the same way. Many deportees who survived were unable to talk about their experiences until years later, either because they found it too difficult to speak about such unspeakable events, or because they were trying to live some semblance of a normal life again. There was also a limited “audience” for their stories, as the truth about deportation and the camps was only gradually coming to light. For a long time, France continued to believe that the Vichy regime never existed in law. The prevailing view was that the Republic had been temporarily transferred to Algiers and London. This was reflected in the decrees that reinstated republican laws, which were passed as early as 1944[2]. The French President Jacques Chirac acknowledged the legal validity of the Vichy regime in 1995, thus paving the way for a new chapter of remembrance for Resistance fighters and deported persons. For example, the French Council of State, the supreme administrative body, was then able to take into account the State’s responsibility for deportation and spoliation, which led to compensation for victims and their heirs.

Continuing to research the lives of Resistance fighters is a way of refusing to let them fall into oblivion, and of keeping their memory alive. Few of the survivors are still alive, and future generations have a duty to keep the flame alive, to ensure that their shattered lives will never be forgotten.

Present and future generations have a duty to remember them, as there are so few written testimonies to pass on their legacy. In France, on April 24 each year, we pay homage to the victims of deportation. In doing so, we make sure they will never be forgotten.

There are stories about the day-to-day life of a doctor and his wife, who was a nurse, during their time in Auschwitz. Eddy de Wind’s book “Terminus Auschwitz” is one such example. This book is one of the few to have been written while the author was actually in the camps, so his memory did not fade over time. The book was published several times in the Netherlands, his native country, initially in 1946, when very few copies were sold. After this first attempt at publication failed, the book fell into oblivion. It was published in France in 2020.

In 1985, Claude Lanzmann made Shoah, a 10-hour documentary film describing the extermination of the Jews, based on eyewitness accounts and footage taken at the scene of the genocide.

Books and films play an important role in resistance, especially those written by survivors or their children. Survival is itself a means of resistance, and by writing books and telling their stories they teach people about what really happened and help to combat the risk of Holocaust denial.

There are now numerous memorial sites in France and throughout Europe dedicated to the victims of deportation and the Resistance movement. In France, in the 1952, a Mauthausen survivor and lawyer, Paul Arrighi, and Annette Lazard, the widow of a man who was deported to Auschwitz and died there, founded the “Réseau du souvenir” (Remembrance Network), which took the initiative to build a memorial to victims of the Holocaust. President Charles de Gaulle inaugurated the memorial, which is in the 4th district of Paris, in 1962 [3]. Since then, many more memorials and study centers have been built, including the Shoah Memorial on rue Geoffroy Lasnier in Paris, which opened in 2005. On March 12, 2024, the Paris Memorial and the authorities in the city of Nice, on the south coast of France, decided to build a second Shoah Memorial Museum in Nice.

Across Europe, several initiatives are underway to preserve the memory of the Resistance and the deportation. The European Parliament, for example, continues to work on Holocaust remembrance [4]; Since 1995, it has passed a series of motions calling for remembrance not only through commemorative events, but also through education. In November 2018, the European Union became a permanent international partner of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). In terms of legislation, the Digital Service Act, which was passed in 2022, is designed to combat online hatred and discrimination, including Holocaust denial.

It is currently considering the idea of erecting a “European monument” in Brussels [5], the idea being to reflect this new approach to Holocaust remembrance, and to involve the whole continent.

The Convoy 77 European project

This Europe-wide project [6] gives schools the opportunity to research and write the biographies of Jewish people wo were deported during the 2nd World War.

Convoy 77, which left Bobigny station on July 31, 1944, was the last major transport of Jews from the Drancy internment camp to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi extermination camp.

1,309 people, including 324 children and babies, were crammed into cattle cars and deported.

The train arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau in the early hours of August 3, and the “selection” was carried out immediately. The official date of death for all of the deportees who were not selected to go into the camp to work was later declared to be August 5, 1944.

At the end of the war, on May 9, 1945, only 251 people who were deported on Convoy 77 were still alive; 847 were murdered in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived.

Spurred on by the advance of Allied troops following the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, and taking advantage of the confusion caused by the failed assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of the Drancy camp, pressed on with his murderous obsession. He was determined not to leave any Jewish children alive, and rounded them up from everywhere he was sure to find them: in UGIF (Union Générale des israélites de France or General Union of French Jews) children’s homes in and around Paris.

More than 300 children (including 18 babies and 217 children between the ages of 1 and 14) were arrested, taken to Drancy and then deported on Convoy 77. Among them were the 20 little girls from the Saint-Mandé orphanage and the manager of the home, Thérèse Cahen, who stayed with them when they were sent to the gas chambers.

For three days, with no food or water and standing up most of the time, Léon travelled locked in a cattle car. As soon as he arrived at Auschwitz, men in gray and blue striped suits made him get out and separated him from the other children: the men had to line up on the left and the women on the right!

The majority of the prisoners (55%) had been born in France, but there were also people of 35 different nationalities. Aside from the French citizens (which included Algerians), they were mainly Polish, Turkish, Russian (in particular Ukrainian) and German.

There were a great many children on this convoy, 324 in total, and 125 of them were under 10 years old.

We took this information from the Convoy 77 website. This non-profit organization plays a vital role both in finding out what happened to the people who lost their lives, and making sure they are never forgotten. The website features work by students from several European countries: we think it would be good if some of them were able to meet each other.

The UGIF

The UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews), was founded by the Vichy government, at the behest of the Germans, on November 29, 1941.

All Jews had to join the organization. This was so that the government could identify them, as their religious background had not been recorded in the census since 1872.

The law under which it was founded in 1941, in common with all the other anti-Semitic legislation that the Vichy regime had enacted since the first anti-Semitic decree on the status of the Jews was passed in October 1940, signaled a break with France’s republican and secular values. There was nothing “republican” about the Vichy government’s anti-Semitism.

The law under which the UGIF was established aimed to merge Jews into a separated population group and to bring an end to their assimilation into the French state. In return, the Germans and Vichy agreed to provide a number of welfare services, at a time when Jews were being forbidden to work in certain professions and their businesses and property were being confiscated, which meant that large numbers of people needed help. Many of the men and women who were in charge of Jewish charitable organizations in the 1930s agreed to run, and work for, the UGIF.

The UGIF took in and cared for children in homes in Paris, including those on rue Lamarck, rue Vauquelin, rue Guy Patin and rue Montevideo, as well as outside Paris in Montreuil, Saint-Mandé and La Varenne, for example. Of the 35,000 Jewish children under the age of 15 who were still living in the Seine department of France in 1941, around 3,500 ended up spending time in one of these homes. It was not long before it became dangerous for Jewish children to be grouped together in one place. German soldiers and the French police often arrested children in UGIF homes.

Source: L’UGIF, collaboration ou résistance ? (The UGIF, collaboration or resistance) by Michel Laffitte, in the Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 2006/2 (N° 185), pages 45 and 64.

The roundup in the home on rue Vauquelin

During the night of July 21-22, 1944, a roundup took place at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris, the headquarters of the Séminaire Israélite de France, (Jewish Seminary of France) which also housed a UGIF home for girls. 33 Jewish girls were staying there at the time, and all of them, together with the staff, were arrested. Many of them were deported on Convoy 77, the last major transport of Jews from Drancy to Auschwitz, which left Bobigny station on July 31, 1944.

Camille Meyer

Among the adults deported from Drancy on Convoy 77 was Camille Meyer (née Belaich), who was 58 years old at the time.

There is very little information available about her, which reminds us of a something that Patrick Modiano said in his book, Dora Bruder (published by Gaillimard in 1997): “These are people who left few traces behind… what we know about them often amounts simply to an address. And this topographical exactitude contrasts sharply with what we shall never know of their lives – that blankness, that chasm of uncertainty and silence”.

Camille was born on August 3 1886 in Algiers, in en Algeria. Her husband, Léon Meyer, who was born on February 24 1877 in Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque, in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France, was also deported on Convoy 77. He was 67 years old at the time. Their last address was 9, rue Claude-Bernard in the 5th district of Paris.

The records reveal that Camille gave birth to a son in Cameroon, and to a daughter, Suzanne Reine, in Marseille, in the Bouche-du-Rhône department of France.

She was arrested at the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin. We have no information about what work she did, but her husband Léon was the manager of the home.

Here is what we found out about Camille Meyer:

- Her name is included on the list of people referred to in a French decree issued on July 3, 1995, which stipulated that the words “Died during deportation” be added to their death certificates (French Official Gazette n°191 dated August 18, 1995): By order of the Minister of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War dated July 3, 1995, the words “Died during deportation” shall be added to the death certificate and declaration of death of: (… ) Meyer, née Belaïch (Camille, Boucris) on August 3, 1886 in Algiers (Algeria), died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland).

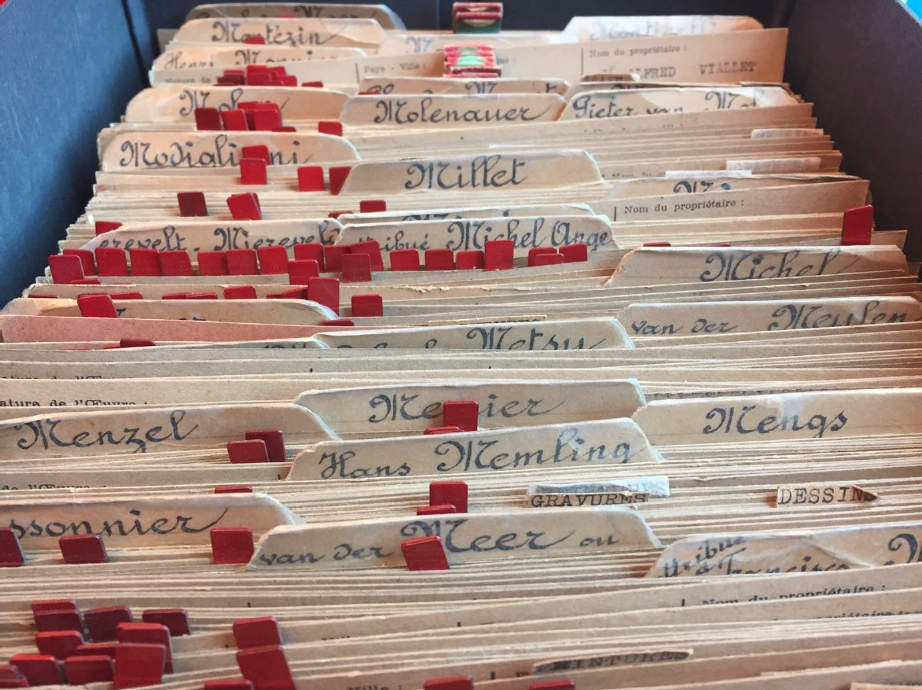

- Camille is also listed in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ documentation on cultural property: 209SUP 35 45.853 “Ms. [Camille] Meyer, Paris”, CRA correspondence and inventory, 11/1945-12/1945. The CRA (Commission de Récupération Artistique, or French artistic recovery service) archives are a collection of records produced by the services responsible for the recovery of cultural property looted during the Second World War. They are drawn from a number of different sources. The CRA was founded according to a decree issued by René Capitant, the French Minister of Education, on November 24, 1944, at the request of Jacques Jaujard, the director of the Museums of France department. It was initially made up of 17 organizations; by 1939, there were to 30. It is based at 20 avenue Rapp in Paris.

CRA (French artistic recovery service) files.

Diplomatic archives, ref. 209SUP/748

We do not know what Camille Meyer did in the Resistance. However, her husband, Léon Meyer was the manager of the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin and his biography can also be found on the Convoy 77 website.

Appendix:

This is taken from the biography of Léon Meyer (1877-1944), which is also on the Convoy 77 website:

Who are we?

We are a group of students in class 4B AFM at the De Viti de Marco high school in Triggiano in Bari, in the Apulia region of southern Italy. With the guidance of Ms. Paola Barone, our French as a foreign language teacher, we first found out about the Convoy 77 project in February 2021. We found the project an interesting proposition: to tell the story of Léon Meyer, a French Jewish citizen who was deported to Auschwitz on the last transport from Paris in July 1944.

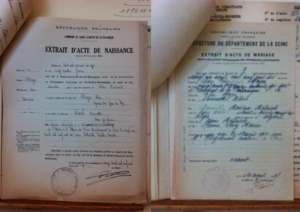

Léon Meyer’s birth certificate and Léon Meyer and Camille Belaish’s marriage certificate:

Bibliography

Archive sources

- Allier Departmental archives, refs. 1580 W 9, 1756 W 2 N° 5860

- Paris Archives, ref. 3595 W 138

- French national library, on the Gallica website, list of naturalizations – Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service

- Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine (Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation) – Civil status register, 7th district of Paris

- Serge Klarsfeld – List of prisoners transferred from Vichy to Drancy on July 15, 1944

- Serge Klarsfeld – Memorial to the Jews deported from France, FFDJF 1978

- Memorial book published by the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation

- French Defense Historical service in Vincennes (Dossier GR 16 P 439315

Articles

- Michel Lafitte’s, “L’UGIF, collaboration ou résistance?” (The UGIF, collaboration or resistance?), Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 2006/2 (N° 185), pages 45 to 64.

Websites

- Enfants juifs à Paris, 1939-1945 – L’enfant et la Shoah (Jewish children in Paris, 1939-1945 – Children and the Holocaust) (lenfantetlashoah.org)

- Serge Klarsfeld – Memorial to the Jews deported from France – Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France – Serge Klarsfeld | Fondation Shoah

- Convoy 77 – Teaching the history of the Holocaust in a different way

- CIVS (the French Commission for Restitution of Property and Compensation of Victims of Anti-Semitic spoilation)

Notes and references

[1] In 1975, Serge Klarsfeld began compiling a list of the victims of the Holocaust in France. The first edition of his Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Deportation of the Jews from France) was published in 1978. Since then, he has published a number of other reference works that have furthered our understanding of Anti-Semitic persecution during the war. He also wrote: Vichy-Auschwitz. Le rôle de Vichy dans la solution finale de la question juive en France (Vichy-Auschwitz. (The role of the Vichy government in the Final Solution to the Jewish Question in France) (1983), Le calendrier de la persécution des Juifs de France (Calendar of the Persecution of the Jews of France) (1993) and Le Mémorial des enfants juifs déportés de France (Memorial to the Jewish Children Deported from France) (1994). The most recent edition of the Memorial to the Deportation of the Jews from France, published in 2012, is the culmination of 15 years’ work

[2] The decree of August 9, 1944 declared that “the form of government is and remains the Republic. In law, it has never ceased to exist”. The aim was to minimize the responsibility of France and the French people for the actions of the Vichy regime, which De Gaulle deemed “null and void” (source: 12th grade students from the Henri IV high school with their teacher, Ms. Morisseau)

[3] Mémorial des martyrs de la Déportation (Memorial to the martyrs of the Deportation) | ONaCVG (The French National Office for Combatants and Victims of War) (onac-vg.fr)

[4] Magdalena Pasikowska-Schnass and Philippe Perchoc, Research Service for MEPs, The European Union and Holocaust Remembrance, European Parliament website, 2020.

[5] Towards a European Holocaust memorial? Touteleurope.eu

[6] Convoy 77 – Teaching the history of the Holocaust in a different way

Français

Français Polski

Polski