Hémy CUPERMANN (1910-1944)

Hémy Cuperman, later known as Henri or Henry, was born on July 7, 1910, in the 4th district of Paris[1]. His parents were David Cuperman and Ernestine Braunstein, both of whom came from Romania and later became French citizens[2].

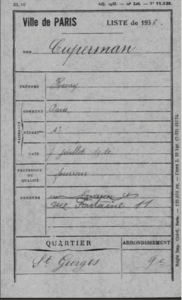

© Paris city archives, 1936 population census of the

Saint-Georges quarter, D2 M8 576

Hémy was one of five children. He had two older brothers, who went on to work in sales, and one sister. The last child was born in 1930, by which time Hémy was already 20 years old.

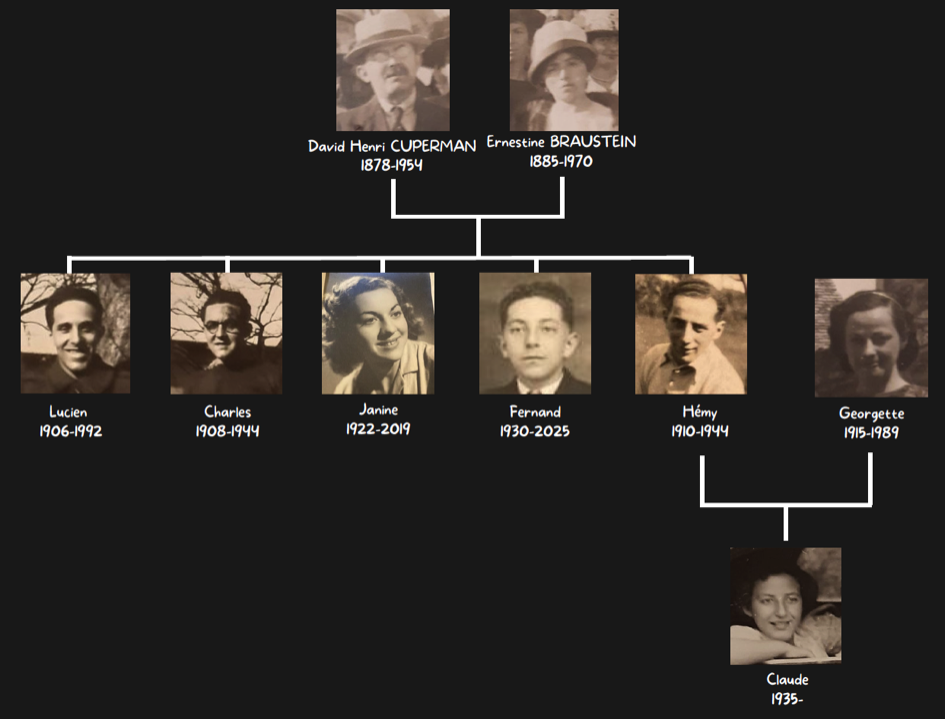

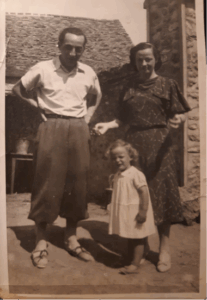

The Cuperman family tree, illustrated with photographs from the Lentzner family’s private collection.

According to his daughter, Hémy met his wife-to-be, Georgette Sigal, at the Alliance Française, a multicultural organization dedicated to promoting French language and culture.

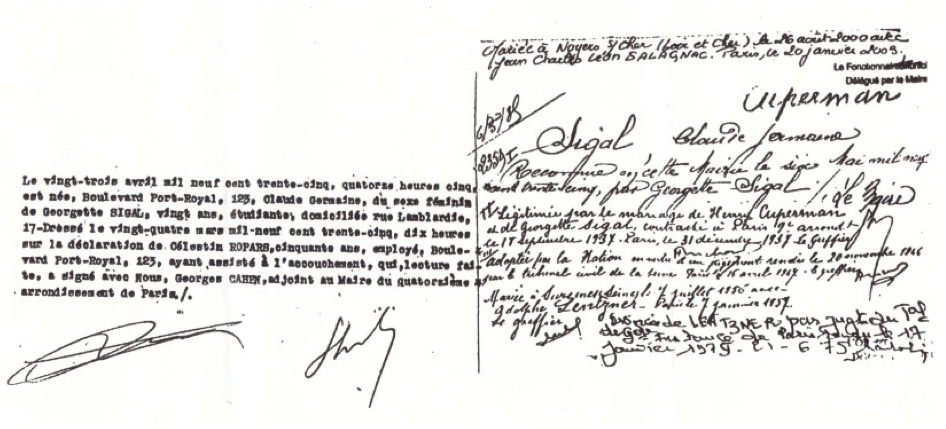

Claude Germaine Sigal Cuperman’s long form birth certificate, issued by the town hall of the 14th district of Paris © Paris city archives

On April 23, 1935, before they were married, Hémy and Georgette had a daughter, Claude Germaine. They did not have custody of her, as her mother was only 20 years old when she had the baby, and this was below the age of majority at the time. In addition, Georgette’s family objected to their relationship, as Hémy was a mere furrier while their daughter was a high school graduate[3].

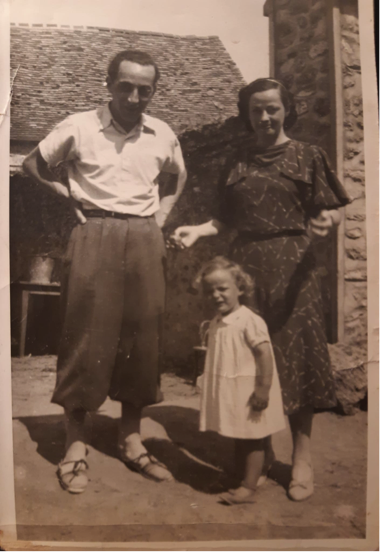

Photo of Hémy, Georgette and Claude Cuperman taken in 1937 or 1938,

© Lentzner family private collection

For the first three years of her life, Claude was raised by a nanny in Brettencourt, in the Somme department of France.

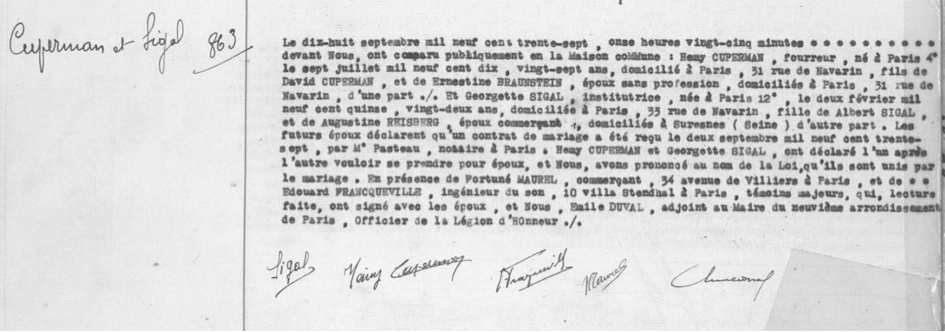

When Hémy and Georgette got married on September 18, 1937, at the town hall in the 9th district of Paris, they were neighbors. They lived at 31 and 33 Rue Navarin respectively, meaning that they were not living together at the time.

Hémy and Georgette’s marriage certificate, issued in 1937, ref. 09, 9M 347

©Paris city archives

According to Claude, her parents took her back in 1939. The family was then living in Suresnes, in the Seine department[4]. Claude does not know what her parents did during the early years of the war. However, she told us that Hémy and Georgette moved to Lyon, in the Rhône department of France, in 1942. They took refuge at 4 Rue Sylvestre in Villeurbanne, on the outskirts of Lyon, with someone who took the risk of hiring Hémy as a furrier despite the fact that he was Jewish. Georgette became the concierge of the building where they lived. They probably chose to relocate to the Rhône department because it was in the “free” zone in the southern half of France, which at the time was not occupied by the Germans[5]. Claude also told us her father got involved with the French Resistance movement, and helped out as a lookout on the bridges in Lyon.

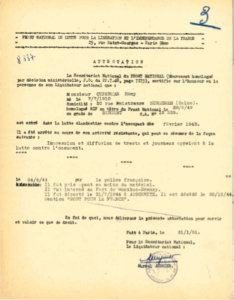

Statement issued by the National Front, dated January 21, 1951.

© File on Hémy Cuperman, French Ministry of Defense Historical service in Caen, Dossier 21 P 439 890

Hémy and Georgette officially joined the Resistance in February 1943. They belonged to the Front National de la lutte pour la libération et l’indépendance de la France (National Front for the Struggle for the Liberation and Independence of France), an organization founded by the French Communist Party. They secretly printed leaflets and newspapers in their apartment, which they then posted and distributed.

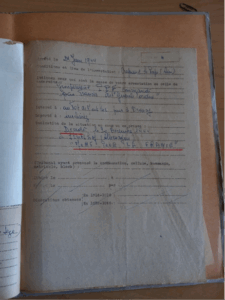

On June 24, 1944[6], Hémy and Georgette were arrested during a round-up in Crépieux-la Pape, a suburb of Lyon. A group of people from the PPF (Parti Populaire Français, or French People’s Party) led by Francis André, who was known as “Gueule Tordue” (“Twisted Mouth”) caught them in possession of flyers and leaflets, and handed them over to the French police[7].

Arrest record. File on Hémy Cuperman © French Ministry of Defense Historical service in Vincennes, Dossier 16 P 152 988

They were taken to the Fort de Montluc prison in Lyon, where they were held from June 24 to June 30, 1944. They were then transferred to the Drancy internment and transit camp north of Paris, which was run by SS commander Aloïs Brunner.

On July 31, 1944, they were both deported on Convoy 77 to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in occupied Poland. They arrived there during the night of August 3 to 4, 1944. They were both selected to enter the camp for forced labor. Men and women were segregated in the camp, which was huge.

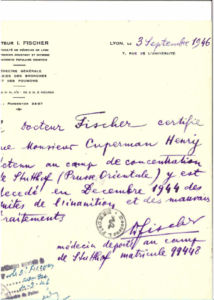

Hémy spent three months in Auschwitz-Birkenau, after which he was transferred to the Stutthof camp in East Prussia in early October 1944. According to a witness statement from a Dr. Fischer, who was in the camp with him, Hémy died there on December 30, 1944, as a result of abuse he had suffered.

Dr. Fischer’s witness statement, dated September 3 1946. File on Hémy Cuperman

© French Ministry of Defense Historical service in Caen 21 P 439 890

After the war, Hémy’s widow Georgette, who survived her time in the camps, applied for husband to be posthumously granted the status of “Deported Resistance fighter”. Her request was denied on December 6, 1951, on the grounds that, although Hémy had been a member of the Resistance, he had been arrested during a roundup rather than while actually carrying out an act of resistance. Georgette then applied for the status of “political deportee” (meaning that he was deported on grounds of his Jewish “race”). Her request was approved on November 3, 1953.

Hémy’s death certificate, dated April 1, 1947, bears the words “Mort pour la France” (“Died for France”). This inscription is not a formal acknowledgement by the French state of Hémy Cuperman’s Resistance efforts aimed at liberating his country[8]. He was however posthumously assigned the equivalent of the rank of sergeant in the R.I.F (Résistance intérieure française, or French Internal Resistance)[9].

Order issued by the French Ministry of National Defense on May 16, 1950. File on Hémy Cuperman © French Ministry of Defense Historical service in Vincennes, Dossier 16 P 152 988

Hémy and Georgette’s daughter Claude was made a ward of the State on November 20, 1946[10].

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to Georgette and Hémy’s daughter, Claude Salagnac, and her children, Valérie and Rémy Lentzner. They kindly shared with us their memories and family photographs and gave us permission to use them in this biography.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Henry, or Henri, (which was the name he usually used) was born at 7 rue des Lions-Saint-Paul, in the Marais neighborhood, in the 4th district of Paris. His parents lived at 62, rue de Richelieu, in the 2nd district, not far from the Bourse. They had moved to France with their families sometime prior to 1905, but had since moved away from the district where most Jews from Central and Eastern Europe settled, and where his grandparents still lived.

Hémy Cuperman’s birth certificate, dated July 1910. © Paris city archives

Did Henry go to school near the Bourse, or in the 9th district, which is where his family eventually settled? Henry’s father was a hatmaker, but neither he nor his brothers followed in their father’s footsteps. Instead, he trained as a furrier.

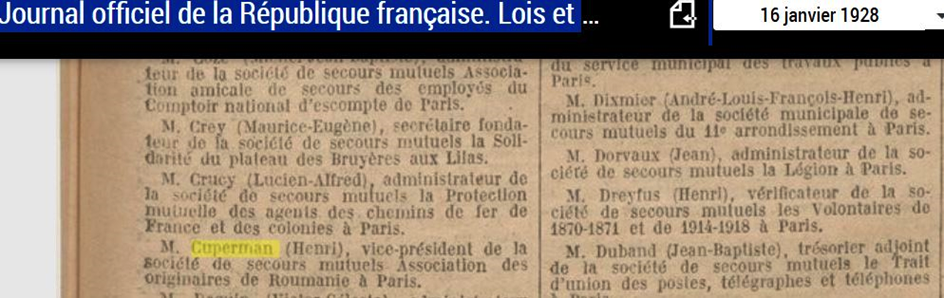

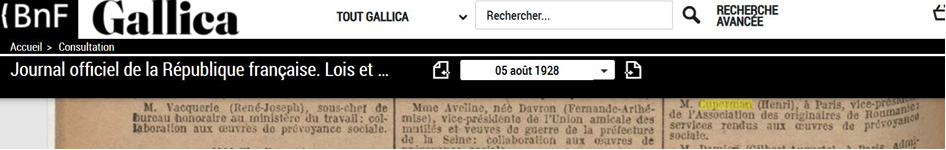

Fully integrated into French society, Henri was actively involved in the social life of his parents’ native community. When he was just 18, he became vice-president of the Société de secours mutuels Association des originaires de Roumanie (Mutual Aid Society of Romanian nationals). This appointment was published in the French Official Gazette on January 16, 1928.

Six months later, as vice-president, he was awarded a bronze medal for welfare work. It is unclear whether this was a Jewish-only organization or was open to all Romanians.

In 1930, he passed the “board of revision” (registration no. 1703) at the 6th office of the Seine (main list). That same year, on April 27, the family’s youngest child, Fernand, was born. His parents left it to his plder sister to arrange the birth announcement, which was published in the French daily Excelsior on May 4, 1930: “Jeannine Cuperman is pleased to announce the birth of her little brother Fernand”.

In 1936, Henry and his father David were on the electoral roll in the St Georges quarter of the 9th district of Paris.

Henry’s voter registration card © Paris city archives

A few years after they registered to vote, both father and son moved out of 31 rue Navarin. David moved to 9, rue Alfred-Stevens, as did his sons Lucien and Charles while Henry rented an apartment at 11, rue Fontaine. He probably did not stay there for long, however, because he, his wife Georgette and their daughter Claude relocated to Suresnes, where Georgette had grown up and her parents still lived. He no doubt continued to work as a furrier in Paris.

The war, and in particular the German Occupation prompted Henri to flee the Paris area and relocate to Lyon. He only returned to Paris briefly when he was interned in Drancy camp, prior to being deported.

Notes & references

[1] His paternal grandparents, Nathan and Seindl, had moved to France by 1905, the year in which his grandfather died.

[2] On July 8, 1905, David Cuperman and Ernestine Braunstien were due to be married; the banns were published, but they did not show up ( Paris City archives, town hall of the 9th district, 1905 weddings). Ernestine was born in Cracova, Romania, on September 6, 1885.

[3] Georgette was a schoolteacher when she married ( with a pre-nup contract). When she returned from camps in June 1945, she stated that she had been a town hall secretary before the war (AN F9 5584).

[4] The address, 20 rue Maistresse is listed in the National Front (part of the Resistance) certificate.

[5] This was no longer the case after the German army occupied the free zone on November 11, 1942, in retaliation for the Allied landings in North Africa (Morocco and Algeria) on November 8.

[6] Georgette said it happened on the 25th, that she was living in Lyon at the time and that she was arrested by the PPF (AN F9 5584).

[7] https://museedelaresistanceenligne.org/media494-Francis-Andr-dit-Gueule-Tordue

[8] The distinction “Died for France” was awarded when it was proven that death was attributable to an act of war, either during or after the actual war. This applied to civilian casualties, bombing victims, etc. Although Henry was confirmed to have been a Resistance fighter and held the rank of sergeant, he was not granted Deported Resistance fighter status. It seems that Georgette did not appeal the decision (too weary of it all, perhaps, having hoped it would be granted and that she would be entitled to compensation)

[9] Among the inscriptions on the tombstone are the words “In memory of our beloved sons who died during deportation as victims of Nazi barbarism” and “To my much-loved husband, To my darling daddy”. Hémy’s brother Charles arrived in Drancy in February 1944, and was deported on Convoy 69. He never came home.

[10] In France, children under the age of 21 whose parent has been killed or injured as a result of war, a terrorist attack or while performing certain public duties are made wards of the State.

Français

Français Polski

Polski