Henri Eichner (1900-1972)

Life for the Jews in the Austrian Empire (1900-1919/1920)

Henri Eichner was born on March 10, 1900, in Brzezinka, near Oświęcim, which in those days was in the Austrian partition and is now in southern Poland. His parents were Israel Joseph Eichner, a butcher, and Jeny Eichner. Henri was one of three children.

When Mr. Eichner was born in Brzezinka in 1900, there was already an elementary school, which started out with one class and later expanded to two. In 1908, the first fire station was built in the village. In 1910, the local residents teamed up to found an agricultural cooperative that made farm machinery available to members, which made the farm work easier and increased crop yields.

In 1914, the outbreak of the First World War turned village life upside down. All the men between the ages of 20 and 50 and fit for military service were conscripted into the army. The village continued to grow however, even during the war, although industrial development was concentrated around the railway junction in Oświęcim. As a result, in 1916-1917, the “Baraki” (Oświęcim II) housing estate, made up of 22 brick buildings and around 90 wooden structures, was built in the Zasole district. In 1919, the Polish army took over the buildings and turned them into barracks. At that time, the “Potęga (Power) Oświęcim” iron and metal foundry was becoming increasingly productive.

After the First World War ended in 1918, when the Austrian Empire collapsed and Poland regained its independence, the village of Brzezinka began to thrive again.

Maps showing the location of Brzezinka in relation to other towns and villages in the Lesser Poland (Małopolska) Voivodeship (region), source: Polish National Archives in Krakow.

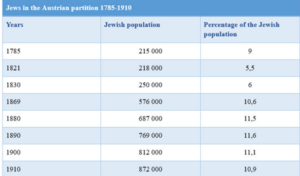

In 1900, the town of Oświęcim had a large Jewish population. Many of them lived in the surrounding villages, including: Babice, Bestwinka près de Kaniów, Bielany, Broszkowice, Brzeszcze, Brzezinka, Bujaków, Bulowice, Czaniec, Dankowice avec Kaniów Dańkowski, Dwory, Grojec, Haręże, Hecznarowice, Jawiszowice, Kańczuga, Kaniów Stary, Kęty, Kobiernice, Klucznikowice, Kruki, Łazy, Łęki, Malec, Międzybrodzie Kobiernickie, Monowice, Nowa Wieś, Osiek, Oświęcim, Pławy, Pisarzowice, Polanka Wielka, Poręba Wielka, Porąbka, Przecieszyn, Rajsko avec Budy, Skidziń, Stare Stawy, Stara Wieś Dolna, Stara Wieś Górna, Wilamowice, Witkowice, Wilczkowice, Włosienica and Zaborze.

Map of Oświęcim and the surrounding area (prior to 1939).

The Jews who lived in Oświęcim played an active role in the town’s political life. In 1904, of the 24 members of Oświęcim’s municipal council, 13 were Jewish.

The Jews also made a significant contribution to economic development in the area. During the first decade of the 20th century, the Jewish community of Oświęcim and the town as a whole expanded and flourished. The opening of a seasonal workers’ employment office run by the National Labor Office and the construction of railway lines had a significant impact on the local economy. The Jewish contribution to the town’s growth was reflected in the founding of the Nathanson and Malcer tar paper and asphalt factory, the Landau and Wolf tar paper factory, and Józef Schönker’s “Union” chemical processing plant. Schönker also took over the Frenkel Brothers & Co. factory, and then founded the Agrochemia fertilizer plant in 1906. There was also the Jakub Haberfeld vodka and liqueur distillery.

The Market Place in Oświęcim (before 1914)

Oświęcim (1900)

In 1910, when the district (powiat in Polish) of Oświęcim was founded, 3,000 Jews were already living there. In 1915-1916, the first secondary school in Oświęcim opened. In 1919, the Kraków Voivodeship comprised 24 political districts, including the Oświęcim district. In 1921, according to the records, the total population of Oświęcim was 12,187, including 4,950 Jews.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a difficult time for the Jewish population, as anti-Semitism began to gain ground in the Austrian partition. The idea that Jews were equal to their non-Jewish neighbors was called into question, as was their integration into the local community. Jews who felt they belonged in the community were accused of cynicism, religious indifference, materialism and being obsessed with money, as well as being sycophantic and focused on climbing the social ladder.

Life for the Jews in Europe between the wars (1919/20-1935)

Einrich (Henri) Eichner lived in Austria for many years before he moved to France and was deported to Auschwitz. After the First World War, the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed and was replaced by the Austrian Republic. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Jews decided to move to Austria, in particular to Vienna. After 1918, the Social Christian Party, a political group that promoted anti-Semitism, became increasingly influential. This is reflected in the Austrian Constituent Assembly elections of February 1919. 72 Austrians voted for the Social Democratic Labor Party (SDAP) and 69 for the Christian Social Party, which epitomized the widespread anti-Semitism in Austria at the time. Over time, the Social Christian Party and the Nazis became increasingly popular. This led to a decline in the Jewish population. Migrants became ever more unwelcome, and it goes without saying that the Jews felt the brunt of the hostility. As a result, during the early years of Hitler’s regime, Jews found it very difficult to move to Austria. In 1933, there were 23,553 Jews, and by 1938, there were still only 27,000. It is worth noting that this small population increase of barely 4,000 can be attributed to births rather than immigration, given the anti-Jewish restrictions on the Austrian border. In 1938, 9 000 Jews were able to enter Austria. Not only did the country not rebel against this anti-Semitism, but it also put Nazi ideology into practice. In 1932, anti-Jewish attacks became more frequent, such as the attack on the “Café Sperlhof”, a Jewish prayer hall, during which a number of people were beaten up and the premises were vandalized. This is further proof of the extent to which the Jews were treated as second-class citizens and of the rise of anti-Semitism in Austria.

Life in Vienna during a period of persecution (1935-1939)

On June 3, 1923, in Vienna, Heinrich (Henri) Eichner married Salomea (Sally) Eichner, who was born in Nesselroth on May 10, 1900. He was working as a butcher at the time. According to the sources, he lived at two different addresses in Vienna: 62, Wallensteinstraße and 5, Karl Maiselgasse.

Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg sought to improve his country’s relationship with the Reich, yet also wanted to safeguard Austria’s independence. On July 11, 1936, he signed the July Agreement with the Reich, which included an amnesty for imprisoned Nazi activists. The Nazis, however, wanted Germany and Austria to become one country. During a meeting between Hitler and Schuschnigg in Berchtesgaden on February 12, 1938, Hitler threatened to invade Austria if Schuschnigg did not give in. On March 11, Austrian Nazi groups seized control of some cities. 72,000 people, most of whom were Jews, were arrested, mainly in Vienna. In April 1938, most of them were sent to the Dachau concentration camp. Jewish organizations were closed down and banned. On March 12, 1938, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler arrived at Aspen airport in Vienna, together with some SS men and police officers, with the intention of taking over the Austrian police force. Hitler and Seyss-Inquart met in Linz that same evening. Hitler announced the Anschluss: the annexation of Austria by Germany. Hitler arrived in Vienna on March 15. A referendum on the annexation, which in reality had already taken place, was scheduled for April 10. There was an unprecedented propaganda campaign throughout Austria. Unsurprisingly, Jews were denied the right to vote in the referendum.

Austrian Jews were regularly assaulted and humiliated. Many lost everything they owned. Josef Bürckel was responsible for the mass deportation of Jews, while Adolf Eichmann was behind the “forced emigration” policy, under which Jews were expelled from Austria. Some 200,000 Jews had been living in Vienna in 1938, but by April 1945 there were only a few dozen left. Jews were banned from owning businesses and working in the public sector.

On the night of November 8-9, 1938, in what became known as Kristallnacht, Joseph Goebbels unleashed a wave of terror and violent attacks on Jews and Jewish institutions throughout the Reich, in Vienna, Klagenfurt, Linz, Graz, Salzburg and Innsbruck, as well as in several towns in Lower Austria. Jews were arrested and deported to concentration camps, in particular Dachau. Almost all of the synagogues were set on fire and their ruins demolished. In Vienna, 42 synagogues were burned down, 27 Jews were killed and 88 were seriously injured. By May 1939, half of all the Jews in Austria had left the country, rising to two-thirds by September 1939.

The war (1939-1942)

Henri Eichner joined the French army as a volunteer in 1939. He was demobilized in 1940. He was arrested on January 3, 1940 in Lyon, in the Rhône department of France, and then interned in the Gurs concentration camp, in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department. He appears to have been released from Gurs sometime in 1943.

In 1938, there were 25,440 Jewish businesses in Austria, but by 1940, 18,800 had been closed down. In the months following the annexation, Jews living in provincial areas had to move to Vienna, and their property and belongings were looted. In February 1941, deportation operations began again.

Sally Eichner, Henri’s wife, was arrested in Vienna on May 1942, and deported to the Izbica concentration camp. She was then transferred to the Majdanek camp. She did not survive.

Majdanek, which was founded in October 1941, was a Nazi killing center near the town of Lublin in occupied Poland. It had its own gas chambers and crematoria.

Henri Eichner’s life and arrest in Lyon (1942-1944)

In July, 1940, Lyon had become the most important city in the free zone. The Paris newspaper industry moved there, and it became the main hub for media organizations and administrative services. In early summer 1940, when the first civilian and armed Resistance groups were founded, a large number of underground pamphlets and flyers were published in Lyon. However, on November 11, 1942, the situation changed dramatically: the Germans invaded the area to the north and occupied the city.

Henri Eichner, who lived at 70 rue Rabelais in Lyon, was arrested on July 5, 1944. He was initially taken to Montluc prison in Lyon, where the Nazi authorities listed his occupation as that of a butcher, and was then moved to the Gurs internment camp. On July 24, 1944, he was transferred to the Drancy transit camp, north of Paris, where he was assigned the serial number 25,692.

Henri was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. He was selected to enter the camp for forced labor and assigned the serial number B-3739. On October 26, 1944, he was transferred from Auschwitz-Birkenau to the Stutthof concentration camp, where he arrived on October 28.

Lyon City Hall (June or July, 1940)

Drancy camp, with a French military police offier on watch (1944)

KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1944-1945)

The prisoners were deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp by train, in appalling conditions. Most of the deportees had no idea where they were going. There was no room to sit down in the cars, so they had to stand for most of the journey. Trains would sometimes stop and leave people stranded on platforms. When they arrived in the camp, the selection process took place immediately. People who were deemed fit to work were sent into the concentration camp, while the others were sent straight to the gas chambers. The new arrivals underwent what is known as the camp admission procedure. Their personal belongings were confiscated (and from then on belonged to the Third Reich), and they had to take a shower before being disinfected, shaved all over and having serial numbers tattooed on their arms.

Until 1944, Jewish men and women were assigned a number from the “general series”, but in May 1944 the camp authorities decided to identify all Jewish prisoners according to a specific numbering system. The idea was to begin the series for Jewish men and women with successive letters of the alphabet. Under this system, from May 1944 until the camp ceased operations, the following numbers were issued :

- 20 000 numbers beginning with the letter A – male Jewish prisoners

- 15 000 numbers beginning with the letter B – male Jewish prisoners

- 30 000 numbers beginning with the letter A – female prisoners

When Henri Eichner arrived in Auschwitz, he was assigned the serial number 3739.

The ramp at Birkenau (1944)

The Jews held in the Auschwitz camp had to wear clothes bearing a yellow triangle and wooden clogs, which often did not fit them. They were not given enough to eat: just a hot, watery drink in the morning, soup at midday and a hunk of bread in the evening. They were forced to work twelve hours a day. Every night, some five to ten prisoners were found dead in the barracks.

Liberation and repatriation to France (1945)

Henri Eichner was liberated on January 27, 1945 and repatriated to France in July 1945.

The events of the Second World War and its aftermath had a huge impact on the Jewish community. The liberation of Jews from concentration and extermination camps was an important milestone in Jewish history. When the war ended, a war reparations process was initiated in order to help compensate the Jews for the harm inflicted on them at the hands of the Nazis.

The liberation of Jews from concentration camps began in April 1945, when the Allied troops crossed into Germany. In the liberated areas, camps were set up for Holocaust survivors. Many of these were makeshift camps in which living conditions were still very basic, but they did at least provide a minimum of protection and met people’s essential needs. War reparations for the Jews were agreed at the Vienna Conference in 1945.

The procedure for applying for political deportee status (1945-1958)

After Henri Eichner was repatriated to France, he was allowed to stay according to four agreements between Poland and France, which were signed on February 20, 1946, September 10, 1946, November 28, 1946 and February 24, 1948.

Henri’s life from 1959 to 1972. His daughter’s investigation into what had happened to him. His descendants.

Henri moved back to Lyon, where he lived until he retired.

While he was still living in Vienna, he married (Sally) Eichner, with whom he had two children, Edith and Kurt. He later married again, this time to Eva Feuerwerker.

Henri died in Lyon on July 1, 1972. His address at the time 10 rue Burdeau, Lyon (record 12/56).

He had two children from his first marriage: Edith Breskin, who was born in 1926, and Kurt Eichner, who was born on January 23, 1927 in Vienna.

Henri’s children are both listed as former owners of the London-based companies K.D. Jewells and Holborn Diamond Polishing Company. These companies are still operating successfully today. The second is now run by Sally Naomi Eichner (Kurt’s daughter, Henri’s granddaughter). We also know Edith Breskin’s has a family member called David Jay Breskin. In 1986, Edith Breskin wrote a letter seeking information about her father. She also applied for compensation.

Français

Français Polski

Polski