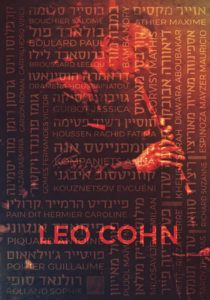

Léo COHN

——————————————————————————

——————————————————————————-

Léo as a Jewish scout in France. Source: Shoah Memorial documentary collection

The chronological biography is followed by a literary biography.

The two biographies

When we decided to study Leo Cohn’s life, about a year ago, the enormous quantity of information and archives available was a little bewildering at first. Compared to previous years, we were faced with a such a wealth of documentation that we wondered what more our investigative work and biographical writing could contribute. There remained gaps to be filled, nevertheless, in the busy life of Leo Cohn, and a remarkable story to be told. This is what we all, teachers and students alike, set out to do.

This year, once again, we have decided to write two distinct biographies, one based on archives and testimonies, which will be finalized next year because we did not have enough time to use many of the archives discovered during our investigation, and the other in a more unusual, literary format.

Léo COHN, chronological biography

This biography was researched, documented and written by students of the Charles Péguy middle school in Palaiseau, France, with the guidance of Ms. Claire Podettin, their history teacher and Ms. Clarisse Brunot, their French teacher.

It is the result of preliminary work on the archives that we acquired this year. It was not possible to use all of them and further research will be necessary to finalize the biography. Further additions may be made at a later date, as well as links to other publications about this interesting individual.

Prior to 1933

Leo Cohn was born in Lübeck, in Germany, on October 15, 1913. He was the third child of Wilhelm Cohn and Mirjam Carlebach. In 1919, the Cohn family moved to Hamburg. Leo started school at the Talmud Torah Gymnasium the following year, 1920. He was quite a good student, as shown by his report when he left the school, in September 1930. He was not as bright as his older brothers, however, and his teachers thought this due to laziness. In fact, the classroom environment was too restrictive for Leo, and the conventional teaching approach did not suit him. His behaviour was nevertheless described as “good, in general”[1]. An anecdote told by his older brother may explain this description. Leo was expelled from school because he spoke up for one of his classmates, pointing out to a teacher that the mark his friend had been given was lower than it should have been. When he got home, he told his father what he had done, smiling proudly. His father slapped him, shocked both by the fact that his son had made such a remark to one of his teachers, but also by the fact that he smiled about it. Léo, for whom fairness was paramount, had not hesitated to intervene. Discussions with his father became heated, and Léo thought briefly about leaving home[2].

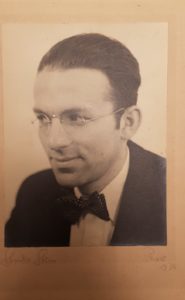

The Cohn house was a meeting place for intellectuals of all nationalities. “All sorts of languages were spoken there by the many foreigners who were our guests”[3]. Lectures and concerts were held regularly in the living room of the big house in Hamburg, as well as the study of the Torah and Greek philosophers in a more intimate atmosphere. Indeed, Léo Joseph Cohen’s maternal grandfather was a very learned rabbi and a scholar of ancient languages. A moment when grandfather and grandson were studying together was once captured in a photograph. Léo (center) and his older brother Alexander were reading the Torah with their grandfather. Absorbed in the subject matter, they took no interest in the photographer. On his father’s side, his grandfather, who died in 1919, was a member of the Carlebach family and he too was an editor and translator of ancient manuscripts.

1- Rabbi Joseph Cohn and his grandsons reading the Talmud, from Noemi Cassuto’s family archives.

This early instruction was to have a profound effect on Léo Cohn. His numerous writings show that he never ceased to expand his knowledge, both intellectual, secular as well as Biblical, and artistic, in order to share it with those around him. This spiritual and intellectual quest continued to inspire him until the very end.

He found inspiration from this background when, during the Second World War, he taught young people in the art of resistance, at the Chantier rural in Lautrec and in other rural workshops[4]. Perhaps Léo also found this same courage to resist in Auschwitz, even deep within the system of oppression, humiliation and dehumanization: “We met up in the Auschwitz 1 Stammlager camp, and you can imagine how emotional that was. We hugged each other and cried. […]

After that meeting, every evening, […] we discussed the Torah, the Psalms […], the Prophets, many passages of which we knew by heart and which gave us inner strength and warmed our hearts […]. We also appreciated medieval philosophy[…][5].

In September 1930, Léo discontinued his studies to attend to his father’s business[6]. In September 1930, Léo discontinued his studies to attend to his father’s business [6]. He left school after the first year of high school, two years before the Abitur examination. He worked in Hamburg initially. However, he notes in his C.V.[7] that “a special schedule granted by the management” enabled him to continue his lessons with his grandfather, learn music and take university classes and even evening classes in French, English and shorthand.

1933

Léo arrived in France on March 27, 1933. He moved in with his parents at 6, avenue Saint Philibert in Paris. He had entered France with a passport issued in Frankfurt am Main on March 24, 1933. On July 1 he made a request for regularization to the Ministry of Labor, in order to obtain a work permit “as a German refugee”. He stated that he was working as a warehouseman at the Compagnie d’Exportation et d’Échanges Commerciaux, at 23 boulevard Haussmann in the 9th district of Paris.[8] This was his father’s company.

He thus became a political refugee and applied for a foreigner’s identity card. He devoted all of his free time to the Éclaireurs Israélites de France (EIF), the Jewish Scouts of France[9].

1935

Léo Cohn’s parents and younger brother emigrated to Palestine. Léo stayed in Paris, where he managed the first of the Jewish Scouts of France premises, “Notre Cité”[10]. He was involved in the ‘council’ and was the Elan, or head, of an organization of more senior scouts called the Clan des Routiers[11], where he soon became a driving force.[12] He also started a choir and small instrumental group.

1936

In January, Léo joined the teaching staff of the Maimonides School, founded by Marcus Cohn, and became a teacher of Hebrew and singing. On February 11, he married Rachel, with Robert Gamzon and Édouard Simon Terquem as witnesses[13]. Léo was 23 years old, and Rachel 20. They had met in school, in Hamburg. Rachel took over from Léo as leader of the ESRA youth movement in September 1930[14]. The marriage was blessed by one of Léo’s uncles, Ephraim Carlebach, the Rabbi of Leipzig, and took place in “Notre Cité“. One of the wedding celebrations was organized by Marcus Cohn, at the Maimonides School.

Following his marriage to Rachel, Léo scaled down his involvement with “Notre Cité” and kept on only the leadership of the choir and teaching Hebrew. The couple were very much in love.

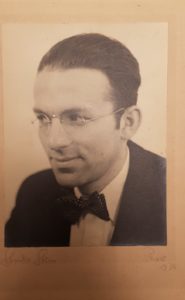

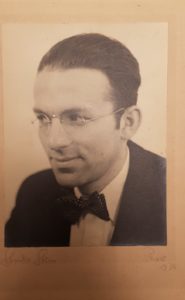

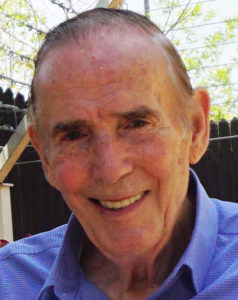

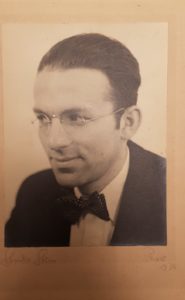

2- Photo of Léo from Noémi Cassuto’s family archives [15]

In this photo, taken in1936, when was 23 years old, he appears quite shy, as if he didn’t dare to look at the photographer from behind his discreet glasses. Was it perhaps taken on his wedding day, by the photographer Fred Stein[16]?

1937

On June 15, Leo applied for a position as a teacher of French, Singing and Hebrew at the Alliance Israélite Universelle[17]. He then hoped to join his family in Palestine.

Léo included a C.V. with his letter, as well as several references from the Jewish Scouts of France., the Consistory and also from one of his teachers at the Realschule of Hamburg. Was he perhaps rejected for this post? Or did he and Rachel decide to stay in France?

1938

Two decrees were issued in 1938, on May 2 and November 12. The first required foreigners to remain under house arrest, while the second changed this to internment, in special centres.

” […] The reasons are clearly stated in the decrees: they were a clear indication of the distinction that the government intended to make between morally dubious individuals, unworthy of our hospitality, and the healthy and hard-working sector of the foreign population […]”.

On January 10, 1938, a letter from the Consistory to the President of the Jewish community in the Lower Rhine area tells us that Shimon Hammel, who at the time was President of the Coordination Committee for Youth within the Jewish Scouts of France, came to Strasbourg to support the candidature of Leo Cohn as a youth leader. The Consistory decided against the appointment of Leo Cohn on the grounds that the post “cannot be entrusted to a foreigner […] but to a teacher who is fully compliant with the laws of the country”[18]. However, a handwritten letter from Léo[19], dated May 31, 1938 and addressed to the president of the Jewish Community in the Lower Rhine, shows how committed he was. In this letter, Léo suggested a series of activities for the Youth Centre, Villa Haas, which had recently been opened for young people from Strasbourg. A program of these activities was then published, and Léo’s proposals were accepted[20].

In 1938, Léo and Rachel were in Strasbourg. Rachel applied for the renewal of her foreigner’s identity card on May 23, and received it on June 24[21]

On September 20th, Léo Cohn wrote to the Prefect of the Bas Rhin department to express his readiness to join the French army if a large-scale mobilization took place. “I, the undersigned, Léo Cohn, of German origin, holder of identity card N°35.C.L. 49.308, asks you to kindly inform him of the place where he might present himself to enlist in the French army in the event of a possible mass mobilization. At such a grave hour for this noble country that has taken him in, he considers it his principal obligation of gratitude towards France and, as a token of his devotion to the country, to make himself available to the authorities to contribute to the defense of his adopted country.”[22]

Noémi was born on October 27, 1938 when the couple were living at 2, place de Zürich[23]. On October 28, Leo wrote to the President of the Jewish community of the Lower Rhine[24] to tell him of the birth of his daughter at the Adassa clinic.

In November, Leo Cohn made his first application for naturalization, in Strasbourg[25].

1939

Following the German invasion of Poland, on September 1, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany on Following the German invasion of Poland, on September 1, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939.

520,000 French nationals were evacuated from the border areas between the Maginot Line and Germany. On September 2, 1939, the French government evacuated people from the city of Strasbourg to Périgueux, Brantôme and Hautefort, in the Dordogne department.

First of all, Leo tried to go to Périgueux. To this end, he asked a number of prominent people to write him letters of recommendation. He also submitted a second application for naturalization[26]. Several testimonials of “good character” were written at Léo Cohn’s request. Might they have been for his application for naturalization? Or perhaps to enable him to go to Périgueux? The first was dated September 25, 1939 (from Isaiah Schwartz, Chief Rabbi of France), followed by others on November 24, (Ernest Weill, Chief Rabbi of Colmar and the Upper Rhine), December 1 (Isaiah Schwartz, Chief Rabbi of France) and December 27 (Joseph Weill)[27].

Unable to obtain permission to go to Périgueux, Léo, Rachel and Noémi moved to Gérardmer where there was an E.I.F. (Jewish Scouts of France) youth center. There they stayed with some “charming people”[28] and Noémi went to a school run by the Sisters of Notre Dame de Sion.

The evacuation had happened in a hurry and people were only able to take 66 lbs (30 kg) of baggage with them. In October, Leo Cohn asked a Mrs. Einstein to go and fetch books and personal belongings from his apartment, and then in December he asked a Mr. Hallel to go and get his wireless radio. In both cases, he gave them a floor plan of the apartment to show exactly where the items were located.[29].

3- Plan of the apartment in Strasbourg, drawn by Léo, from Noémi Cassuto’s family archives

These plans depict a small three-room apartment, with an office, living room, bedroom and kitchen. On them, Leo drew the bookshelves of his office and the living room. They include his childhood books, works in French, German (philosophy, literature, history, science and religion), English, as well as a shelf devoted to music (Beethoven, Brahms and songs).

In order to avoid internment, Léo decided to join the Foreign Legion, which was the only means of leaving the region, as he explained in a letter to his parents[30] “if I have not left, that is to say joined, either the French or related [forces], the rules involved mean that I cannot dream of moving”.

Emergency legislation concerning “nationals of enemy states”.

On September 1, 1939, two days before the declaration of war, a Decree was issued that, in the event of a conflict, provided for “the assembly of all foreigners from lands belonging to the enemy” of the male sex and aged between 17 and 50 years old. 4 days later, a circular was sent out asking them to go to the assembly centers to which they had been assigned. On September 14, men aged 50 to 60 were in turn summoned to be interned.

Joining the Foreign Legion was a means of escaping this internment. However, the military ensured that these new Legionnaires were not allowed to fight on French territory, since the Chiefs of Staff were opposed to deploying Germans against Germany “for reasons of international law and common practice”. They were therefore transferred to North Africa.

On December 15, 1939, a few days before his departure, Léo wrote to his family from Gérardmer. The letter is in French. He describes little Noemi with affection and humor. He also mentions his upcoming departure for the Foreign Legion, the possibility of being posted to Africa or Syria and his preference for the latter, writing “how glamourous that would be!”[32].

On December 26, he became a member of the Foreign Legion[33] for the duration of the war. He was recruited into the Army Service Corps in Épinal. He joined the First Foreign Infantry regiment with the regimental number 91385[34]. He was sent to Sidi Bel-Abbès, in Algeria, where he arrived on January 31[35].

4- Léo as a Legionnaire, Noémi Cassuto’s family archives

1940

Rachel and Léo communicated by letter, as did little Noémi. She wrote to him through her mother, who kept her sweet, childish language: On May 31, she wrote “My dear darling Pappi, Mommy is so happy because she sent you some nice things. I’m sending you this picture to make you happy, me too. This castle [Saint Céré and Tours Saint Laurent, in the Lot department] we can it see from our window, we live opposite. I hope you’ll come to play with me soon. I already know a lot of games and you won’t be bored with me! We got some roses from a peasant girl. Mommy put them in a vase with your picture and the candles on the table on Saturday. That was lovely! Big kisses from Noémi.”.

On July 14, she wrote “Daddy, I’m standing at the edge of the table with your picture on it. I pick it up all the time and kiss it, it’s because I haven’t seen you for such a long time, I want to see you now, and hug you and play with you. And talking to my daddy, I’m already looking forward to it so much. See you soon. Your little Noémi”[36].

In May of that year, Rachel wrote to the Prefect of the Vosges department to find out whether Léo’s application for naturalization had been forwarded to Paris[37]. The reply said that the file was being processed.

The Vichy Decree on the review of naturalizations was issued in July. It was decided that all acquisitions of French nationality since the passing of the Nationality Act of August 10, 1927, would be reviewed. In all, nearly 7,000 Jews were officially denaturalized.

Rachel had left Paris for Saint Céré and then, at the beginning of August, went to Moissac, where she wrote “there is a maternity hospital where I hope to be able to give birth in less unfavorable circumstances”. Léo was still serving in the Foreign Legion.

After the debacle in Algeria, the Foreign Legion troops were not demobilized. Leo’s unit returned to the base at Sidi-Bel-Abbès.

Rachel gave birth to her baby, Ariel, on August 17 in Moissac, far away from Léo.

A few days later, on August 14, Léo wrote to his parents from Sidi-bel-Abbès and in particular to his mother, for her birthday. He wrote the letter in French. “How far and yet how near, both at once, are the times when, on your birthday morning, we lined up by your bed to bring you our greetings, and our love… and this little treat became a tradition, often accompanied by a few “chutzpedick” lines from this little man”

Léo described his life in Sidi-bel-Abbès, in the “fortunate” company of musicians. Léo himself was a “learner of the fife”, an instrument very different from his “dear old tin whistle”, and which he compared to a flute. “When I first arrived, I didn’t know how to make the slightest sound from it, but now (without flattering myself too much and to the great amazement of my comrades) I play everything I’m asked.” A memo from Major General Beznet, dated November 14 confirms that Leo had been released. He returned from the Legion in December 1940[38] and went to join Rachel and Noémi in Moissac.

On October 4, an anti-Semitic and xenophobic law was passed, which subjected foreign Jews to arbitrary detention by the police by giving Prefects the power to intern “foreigners of the Jewish race” in special camps.

Article 1 of this law said: Foreign nationals of Jewish race, from the date of the enactment of the present law, are to be interned in special camps according to the decision of the Prefect of the department in which they reside.

Article 3: Foreign nationals of the Jewish race may at any time be subjected to forcible confinement by the Prefect of the Department in which they reside.

1941

While the Vichy statutes mentioned everything that was forbidden to Jews, they also implied that certain things were not. First and foremost, agricultural jobs were not on list of prohibited activities. This is the reason that Jewish organizations such as the Jewish Scouts were able to provide professional training courses related to rural occupations, some with the support of Vichy. The concept of a return to the land had been advocated by Robert Gamzon even before the war, and was thus in keeping with what Vichy wanted to encourage. The first permanent center was set up in the commune of Lautrec, in the Tarn department, and catered for around forty young people between the ages of 16 and 25. The second was in Taluyers, in the Rhône department, and the third in Viarose, in the Tarn et Garonne. These centers managed to stay open to provide education for Jews and were generally well accepted by the local community[39].

On January 22, 1941, Léo and Rachel moved to Lautrec[40], a small town about ten miles from Castres, in the Tarn department.

Lautrec was a rural workcamp set up in November 1940. The complex included several farms, artisanal workshops and a training center. An initial group moved to the farm in La Grasse on November 11, and a short time later, another team converted the premises of what was to become known as the “Chantier Rural de Lautrec” in the outbuildings of the Château de Lautrec. Lautrec was a relatively large estate in a poor state of repair, but the outbuildings provided accommodation for about forty young people. At the farm at La Grasse, about a mile away, where the E.I.F. group were sharecroppers, they were “Défricheurs” [people who cleared the land ready for cultivation][41].

They were housed on the ground floor of the Maison d’Estampes, an old 17th century house with very basic facilities. There was electricity, but no running water. They had to fetch water from a well a hundred yards or so from the house. In the winter, it was a long way! Léo taught the children in the house to draw water with a bucket. The rooms were heated by small wood-burning stoves[42]. The Gamzon family, (Robert, his wife Pivert, and their two children), as well as the Pulver couple and their twins were also living in the house.

In November, Léo applied to the Refugee Service of the Tarn department for an allowance. He said that he was working as an “agricultural apprentice” at the Lautrec rural workcamp, and declared that he was not receiving a salary, just a small allowance, from the workcamp. He explained that he had been a student before he was evacuated. The mayor of Lautrec rejected this request on the grounds that “A 28-year-old farmer: at that age he can support himself. Children receive the refugee allowance“[43].

On April 15, 1941, Léo Cohn received a foreigner’s identity card, N°0018, issued in Lautrec and valid until March 9, 1942[44]

Léo founded a Jewish Scouts of France newspaper, called Sois-Chic (Be Chic). It was a wall poster publication for the Défricheurs at Lautrec. From December 1941 onwards, there was also a “reduced” version, which was sent to all the Jewish Scouts of France groups. Publication dates were random[45] because Léo was short of contributors. He lamented this in the December 1941 issue: “Everyone can have their say, everyone can participate, everyone must feel responsible for Sois-Chic”. This publication will then become a reliable reflection of the soul of the camp. Look good in this reflection, be elegant, be “chic”!” The content of the paper was very varied, focusing on lambing, stories, and even an article on Judaism in the workcamp.

In Lautrec and in the other rural camps and children’s homes run by the Jewish Scouts, Léo was able to practice his talents as a teacher and choir leader. He taught Hebrew[46], was one of the instructors for the Jewish Scouts leaders’ training courses, and was also a religious leader. Teaching was in his heart and soul. Regardless of whether a person was a child or an adult, and whatever his or her intellectual ability[47], he wanted to impart and share not only his knowledge, but his philosophy of life. This appetite for teaching began when he was very young, as mentioned by one of his teachers, Dr. Joseph Jacobsen, from the Talmud Torah school[48].

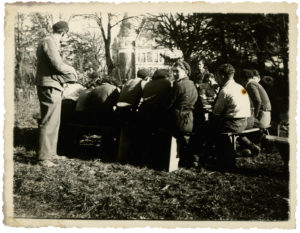

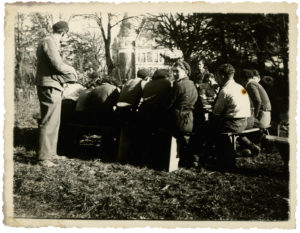

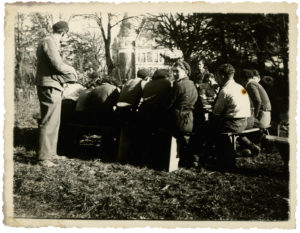

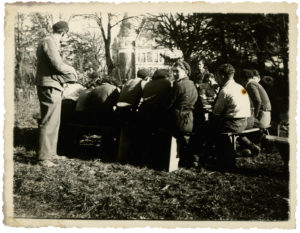

5- A group of young people working in the grounds of Château de Lautrec, under Léo’s watchful eye. Shoah Memorial archives

5- A group of young people working in the grounds of Château de Lautrec, under Léo’s watchful eye. Shoah Memorial archives

6- Léo officiating, Shoah Memorial archives, ref. MXXXVa_6

Music and singing were important to Léo, and also, he was sure, for the “pioneer” group that he led. Singing helped to unite the community in joy and fellowship, and it was also a way of living a more cheerful Jewish life, a necessary accompaniment to the hard work on the land at the Lautrec rural workcamp.

1942

The small booklet handed out to the audience tells us that among the sopranos was Léo’s wife, Rachel, who was described as the “Mother of Estampes”. The choristers came not only from Lautrec, but also from various other places, such as Moissac and Marseille… The repertoire was varied: classical choirs (Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Haëndel) and synagogue choirs, as well as popular French, Palestinian and Jewish songs. During the concert, Castor addressed the audience.

The choir was very popular, as Leo wrote in the February 1942 issue of Sois-Chic: “We went to preach the return to Earth, but we were told that we had returned to Heaven. Is Lautrec in Heaven? Is the workcamp like one of those spherical temples in which visionaries imagine the Seraphim devoted tirelessly to divine service?”[50]. Yet in Lautrec, Léo’s chosen approach was sometimes criticized: “May the admiration of city people, who took our singers for angels from a better world, open our eyes so that we discover the value of our new life”.

In April, he wrote to a man named Lucien, with whom he disagreed on matters of religious practices. The document in the family archives [51] appears to be a draft, written in pencil. Perhaps it was never sent? In this letter he expresses his deep disagreement with Lucien, whom he calls “orthodox”, reproaching him for superficial, unfounded explanations and even for his audacity and his presumption. He appears to be replying to a letter that he had received, in which Lucien reproached him for his anger and aggressive tone. Discussions in Lautrec seem to have been very lively. Leo’s introduction of “Neo Hasidism” was not acceptable to everyone, whether they were “orthodox” or, on the contrary, declined to practice religious rites.

On May 1, Leo wrote to Chameau[52]. In this letter, he again mentions internal disputes between the leaders of the Jewish Scouts. He expresses his disappointment that the young people in the workcamp did not respect the Sabbath. He regrets not having been able to accomplish the mission that Robert Gamzon had given him “to readapt Judaism to country life”. Elsewhere in the letter, Leo describes with great tenderness the “exploits” of Naomi and Ariel. A whole page is dedicated to them the love and admiration of a father for his children is evident.

7- Noémi, Rachel, Léo and Ariel, Noémi Cassuto’s family archives

Léo made numerous trips to the various Jewish Scout centers, in particular in the summer, a busy period in the agricultural calendar, when the workers did not have time for studies or deep discussions: “From the 1st to 12th of June, I shall camp with Loinger at Montintin [a children’s home run by the O.S.E, a Jewish Children’s Aid Society.], and I shall take the opportunity to stop over in Périgueux, where they are making preparations for an Oneg-Coco on the 13th. Afterwards, if my papers allow it, I shall make a visit to Beaulieu [a Jewish Scouts’ children’s home]. From the 19th to the 29th of July, I have to camp with the Routiers [more senior scouts]. From August 27th to September 7th I will go to Montserval [a Jewish Scout school camp]. On or around August 12th, Musa is getting married in Haute Savoie. If I have to go there, I would like to spend some time in a real training course at your place. (…) The only unpleasant thing about all these trips is leaving Rachel all alone the whole time. But Rachel herself is happy to see me immersed in the “world” again.” [53].

On August 25, in Vichy, Robert Gamzon heard that a raid was to take place in the Southern zone. On August 26, 1942, he called a meeting of Jewish Scouts leaders, in Moissac, where they laid the foundations for the future clandestine movement: la Sixième, or the Sixth.

1943

In 1943, in the face of increasing danger, the Jewish Scouts national team decided to disband all of its centres, children’s homes and rural workcamps. Léo, Rachel and the children moved to a small house in a hamlet called La Caroussinié, in the municipality of Labessonnié, about 2 miles from the village of Lautrec. They adopted the surname Colin. We know that Léo had false identity papers thanks to Aviva’s birth certificate, on which he declared that his name was Léon Bernard Colin, born in Bourbach in the Haut Rhin department. Rachel’s name was given as Renée Schmitt, born in Bischwiller in the Bas Rhin department.

Rachel gave this account of that secret life: “We left Lautrec in 1943, for life in the Maquis [an underground Resistance movement]. To tell the truth, it wasn’t an organized Maquis group. We went to live in a small house that Toulouse-Lautrec’s family had made available to the Jewish Scouts. (…) We lived in this little house for a year and a half, and we took in young people. There were as many as eight or ten of us in the house and we led a truly peasant life, although that did not prevent us from maintaining an active spiritual life as well. In the evenings, with the fire burning in the hearth, we read French classics. We passed for Adventists, a sect that celebrates the Sabbath. We had false papers in the name of Colin, as did our two children. As for my daughter, born in March 1944, she had a “genuine false identity ” from the moment she was born, and when we arrived in Israel, we had great difficulty proving that she really was our daughter…”

We still published “Sois Chic”. We were in contact with all the leaders of the Sixth and in particular with Hammel, who was in charge of organizing children’s crossings into Switzerland, under the aegis of the Jewish Scouts of France (E.I.F.).”[55].

On 18 September, a search warrant was issued by the Prefecture of Police of the Tarn department since Léo Cohn “had left, without authorization, the commune where he was under house arrest”, and should “be taken under heavy escort to the camp at Noé, by Muret.”[56].

The development of the Sixth’s military arm took place in two separate phases. On December 16, 1943, a group of eight scout leaders and young farmers formed a Maquis group at an abandoned farm, La Malquière, in a remote corner of the Sidobre area of the Lacaune mountains, to the east of Vabre in the Tarn department. Then, on April 29, 1944, a similar group, also from Lautrec, which by this time had shut down, formed another Maquis group in an old, ruined farm at Lacado, about 4 miles from La Malquière. The commanders of the French Forces of the Interior, in Vabre, made La Malquière into a military training center for local Resistance fighters[57].

Shimon Hammel recalls this secret meeting: “Bouli (Simon) and I were given orders to go to the Montagne Noire area, near Castres. We were to find Leo Cohn and other chiefs and elders in a woodcutter’s hut, and there we were to lay the foundations of a Jewish underground movement. This is one of my most moving recollections. We had in mind appointing Gamzon as captain, Gilbert Bloch as lieutenant, and Roger Kahn and Adrien Gainsburger as second lieutenants of the Jewish resistance. I, who had never progressed beyond the rank of sergeant, had to appoint a captain and three lieutenants.

We arrived at nightfall at this wooden hut in the middle of the forest, it was very cold. We had a great philosophical discussion on a Jewish subject, dominated by Leo. It lasted until half past midnight. Then we asked Roger Kahn and Adrien Gainsburger to come out, and in the moonlight, in the frost of the forest, we made them both lieutenants of the resistance group. It is one of my most poignant memories.

This military ceremony in the forest, in the silence of the night, with these Jews who had always been peaceful people“[58]

1944

On March 2, 1944, Aviva was born on rue de la Tolosane in Castres, under the name of Yvette Colin. [59]. Noémi and Ariel remember having walked a very long way the day before, in the cold, to get from the house where they were hiding to the town of Castres.

In a letter to Hardy in April 1944,[60] Léo describes, in a coded message, his upcoming departure with a group of young people: “We are facing a clear and decisive turning point in our activities and our position. We have had to close all our farms and circles [? illegible] and those who have not yet had to leave for the STO [the compulsory labor service] have had to find their own solutions. I’m going to try to run a farm with a few brave people on my parents’ side. I would like to see you before getting into this. I will be in Lyon on May 3rd[61]. Do you want to write to me in advance, or there, care of the post office, or to make an appointment at your convenience?”. However, the meeting in Lyon never took place, since Hardy’s reply arrived too late[62].

On May 7, Léo took Rachel and their three children to the Swiss border, close to Annemasse. The border crossing was delayed by a day because Leo and Ariel said their prayers in the morning and as a result the family missed the train that was supposed to take them to Annemasse. This prayer saved their lives, as the train was searched and all the Jews were arrested. took them across the border. Léo had entrusted her with his family after a final farewell. Noémi remembered forever these final moments that the family spent together. They had to hurry to get through between two German patrols guarding the border. Nevertheless, Léo took the time to bless his children and promised them that they would meet again in Palestine. The group the set off, and when Noémi turned around, she saw her father waving at her for the last time. To get under the barbed wire, Noémi and Ariel were wrapped up in a blanket. Each child was passed through separately. Ariel remembered the guard and his rifle, and how afraid he felt because he thought he was a German soldier.

Back in the little house, on May 11, Leo wrote his first letter to Rachel: “I’m longing to hear from you. I think about you all the time”[64]. He asked about little Aviva, and even gave Rachel some advice on how to feed her: “Do it [breastfeed Aviva], it is still best, don’t give dried milk, but add orange juice on a spoon from the 3rd month”. In this letter Léo also described his final preparations and recent meetings, and said that he would definitely be leaving on the Monday, which was May 15.

Léo was arrested on May 17, 1944, at the station at Saint Cyprien, near Toulouse, along with Jacques Roitman[65], Hermann-Hubert Pachtmann[66] and three other members of the Resistance. Rachel thought that was turned in[67]. He was supposed to be taking some young people to Spain, and was arrested just as he was about to board the train. He had barely enough time to swallow the sheet on which the names of the young people were written.

Abraham Block witnessed the arrest. It was he who took the young people to Spain, and then, in October 1944, to Palestine [68]. Léo was first imprisoned in Saint Michel prison in Toulouse, together with Jacques Roitman. Robert Gamzon tried to get a message through to him to find out whether he was arrested as a Resistance fighter or because he was a Jew. This task was given to a woman called Elsa Baron, but she was unable to do it[69].

Léo was sent to Compiègne[70] initially, as a member of the Resistance. He was then transferred to Drancy on July 6, where he was given the number 24895.

Léo wrote his final letters to Rachel, the children and his friends. These letters were smuggled out of Drancy. Was it the camp doctor who took them out, as Ariel believes, based on what Rachel told him? Or a network of resistance fighters inside the camp, as Aviva believes, according to what Rachel told her? Or perhaps both? He asked about his children, in particular about little Aviva’s health, and mentioned that he was in good physical shape.

He finished work at the camp metalwork shop[71] to take care of and play with some children. “I’m heading to an unknown destination and there are 300 youngsters in the convoy! There are no complaints about their treatment, but it’s such a pity to see so many who do not know who their mothers and fathers are, and don’t even remember their names! I often play with these children; I left the locksmith’s shop for them. I fought tooth and nail to go with them in the wagons, but it was impossible, “single” men are subjected to a harsher regime and held separately”[72].

Between July 21 and 25, 1944, a series of raids on Jewish-run children’s homes in the Paris area resulted in the arrest of 250 children and 33 members of staff. All of them were deported on Convoy 77, on which there were 330 children under the age of 18.

He started a choir, but “every day its membership changes and it’s hard to get anything done,” he wrote[73]. After the war, Shimon Hammel took a photo of some graffiti[74] drawn by Léo, the last trace he left before he disappeared. Leo remained profoundly religious and practiced his faith to the very end.: “I’ve broken the fast now, at 4 pm, because tonight we are leaving and I’ve just been shorn and shaved. Yesterday evening, with two boys and four girls, I read the scroll of Jeremiah”[75].

Léo was deported on July 31, 1944, on Convoy 77. In the cattle car, he organized one final choir for young women. Those who survived later recounted that he had encouraged them “to stick together and to sing as loudly as possible, to give strength to the group. In Buchenwald they were nicknamed “Les Françaises qui chantent“ (The singing French women)”.[76].

Even in those most difficult of times, in Drancy with all the orphaned children and in the cattle car that took him to Auschwitz, Léo found in his heart the strength to lead a choir, to bring a little comfort to those around him.

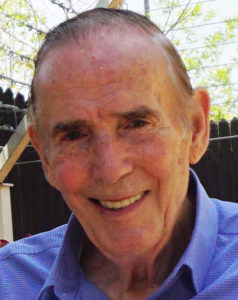

Léo was among those who was chosen to be sent into the camp to work. Transferred to the Echterdingen camp, he died of exhaustion on December 28, 1944.

While searching the archived documents, we found a letter from Robert Weil, in which he describes the last moments he spent with Léo in Auschwitz. We were all moved by its pertinence, and it is with this excerpt that we would like to conclude: “I was trying to convince Leo to see things from a more rationalist angle, [at least] I was under that impression at the time. I have changed since then. […] Reality is only an illusion; it depends on the way in which it is approached. [ …] One has to bring about one’s own transcendence. […] I was young at the time, having had a Cartesian education. Leo had more contact with the imaginary world, being a musician and poet, and he was nearer the mystical, close to the Masters, who were “intoxicated with God”.».[77]

Biografie von Léo COHN

Léo als Pfandfinder der éclaireur israélite de France (EIF), Dokumentenbestände aus dem Mémorial de la Shoah.

Die Biografie wurde von den Schülern des Collège Charles Péguy de Palaiseau, unter der Leitung der Geschichtslehrerin Claire Podetti und der Französischlehrerin Clarisse Brunot, recherchiert, dokumentiert und verfasst.

Diese Biografie ist das Resultat der ersten Bearbeitung der Dokumente und Quelle, die wir dieses Jahr gesammelt haben. Wir konnten nicht alle Quellen bearbeiten, sodass noch einige Recherchen notwendig sind, um die Biografie zu vervollständigen und fertig zu stellen. Daher ist es möglich das noch Veränderungen und Ergänzungen vorgenommen werden.

Vor 1933

Léo Cohn wurde am 15. Oktober 1913 in Lübeck geboren. Er ist das dritte Kind von Wilhelm Cohn und Mirjam Carlebach. 1919 zog die Familie nach Hamburg. Léo besuchte ab 1920 das lycée Talmud Torah. Er war ein guter Schüler, was durch sein Abschlusszeugnis deutlich wird. Dennoch waren seine älteren Brüder besser und seine Lehrer fanden, dass er faul sei. Tatsächlich, hatte Leo Schwierigkeiten, da der klassische Unterrricht nicht zu ihm passte. Sein Verhalten wird als« bon, en général »[1], also gut im Allgemeinen, beschrieben. Eine Anekdote, die sein älterer Bruder erzählte, kann dies vielleicht erklären.

Leo wurde von der Schule verwiesen, weil er einen seiner Klassenkameraden verteidigt hatte und er den Lehrer darauf hinwies, dass die Note, die er ihm gegeben hatte, niedriger war, als sein Klassenkamerad hätte haben sollen. Zu Hause erzählte er seinem Vater von seinem Einsatz und war sichtbar stolz darauf. Sein Vater ohrfeigte ihn, schockiert sowohl über die Tatsache, dass sein Sohn dem Lehrer widersprochen hatte, als auch darüber, dass er stolz darüber lächelte. Es folgten lebhafte Diskussionen und Streit mit seinem Vater, und Léo dachte eine Zeit lang darüber nach, das Familienhaus zu verlassen [2].

Das Haus der Familie Cohn war ein Ort, an dem Intellektuelle aller Nationalitäten zusammenkamen[3]. Es fanden sowohl Vorträge und Konzerte, als auch Studien über die Thora und die griechischen Philosophen in dem Wohnzimmer im hamburger Wohnhaus statt. Der Großvater von Leo Joseph Cohen mütterlicherseits war ein gelehrter Rabbiner und Experte für alte Sprachen. Ein Foto hält diesen Moment fest, in dem der Großvater und die Enkel gemeinsam in der Thora lesen. Auch der 1919 verstorbene Großvater väterlicherseits der Familie Carlebach, war Herausgeber und Übersetzer alter Manuskripte.

1- Der Rabbiner Cohn mit seinen Enkeln, wie sie im Talmud lesen. Familienarchive Noémi Cassuto

Die Lehre durch seinen Großvater wird Léo Cohn stark prägen. Seine zahlreichen Schriften zeigen, dass er nie aufgehört hat, sein intellektuelles, biblisches und säkulares – aber auch künstlerisches Wissen zu erweitern, um es mit den Menschen um ihn herum zu teilen. Diese geistige und intellektuelle Suche beschäftigte ihn bis zum Ende.

Daraus schöpfte er auch Kraft, als er während des Zweiten Weltkriegs, als jungen Mann im Chantier rural de Lautrec lernte, Widerstand zu leisten [4]. Auch in Auschwitz, wo Unterdrückung, Demütigung und Entmenschlichung ihren Höhepunkt erreichten, fand Leo die Kraft, weiterhin Widerstand zu leisten: « Nous nous sommes rencontrés au camp d’Auschwitz 1 Stammlager avec l’émotion que tu devines. Nous nous sommes embrassés et nous avons pleuré. […]

Zitat: „Dès cette rencontre, tous les soirs, […] nous discutions de la Torah, des Psaumes […], des Prophètes dont nous savions de nombreux passages par cœur et qui nous redonnaient de la force intérieure, la chaleur de l’âme []) Nous aimions aussi la philosophie médiévale […]“[5]

Im September 1930 unterbrach Leo sein Studium, um sich um die Geschäfte seines Vaters zu kümmern. Er war in der 11. Klasse und es blieben ihm noch zwei Jahre bis zum Abitur. Er arbeitete zunächst in Hamburg. Er präzisiert jedoch in seinem Lebenslauf[7], dass er mit Erlaubnis der Schuldirektorin, dem Unterricht seines Großvaters folgen durfte und so Musikunterricht bekam, Universitätskurse und sogar Abendkurse in Französisch, Englisch und Stenographie besuchte . .

1933

Am 27. März 1933, kam Léo in Frankreich an. Er wohnte zunächst bei seinen Eltern in der 6 avenue Saint Philibert in Paris. Er ist mit einem Pass eingereist, der am 24.Mai 1933 in Frankfurt ausgestellt wurde. Am 1. Juli beantragte er beim Arbeitsministerium eine Arbeitserlaubnis. Er erklärte, dass er als Stauer bei der Compagnie d’Exportation et d’Échanges commerciaux, 23 Boulevard Haussmann im 9. Arrondissement, [8] in der von seinem Vater gegründeten Firma, arbeitete.

Er war also ein politischer Flüchtling und hatte einen Personalausweis für Ausländer beantragt. Er verbrachte seine gesamte Freizeit bei den Éclaireurs Israélites de France (E.I.F.)[9].

1935

Die Eltern von Léo emigrierten mit seinem kleinen Bruder nach Palästina. Léo leitete die « Notre Cité»[10], das Zentrum der E.I.F. Er war Mitglied des« Conseil municipal » und des clan des routiers[11] wo er einen wesentlichen Anteil beitrug[12]. Er gründete einen Chor und ein Musikensemble.

1936

Im Januar wurde Léo Lehrer für Hebräisch und Gesang an der Maïmonide Schule, die von Marcus Cohn gegründet wurde. Am 11. Februar heiratete er Rachel unter Anwesenheit von Robert Gamzon und Édouard Simon Terquem[13]. Léo war 21 und Rachel 20 Jahre alt. Sie haben sich in der Schule in Hamburg kennengelernt. Rachel hat 1930 die Nachfolge von Léo bei der Führung des mouvement de jeunesse ESRA angetreten[14]. Die Trauung fand in der« Notre cité » statt und wurde von Ephraïm Carlebach, Rabbiner von Leipzig und Onkeln von Léo durchgeführt. Eine der Feiern fand in der Maïmonide Schule statt.

Nach der Heirat, reduzierte Léo seine Aktivität bei Notre Cité und blieb nur noch Leiter des Chors und der Hebräischkurse.

2- Fotografie von Léo, Familienarchive Noémi Cassuto [15]

Auf diesem Foto von 1936 ist Léo 21 Jahre alt, er wirkt sehr schüchtern, da er den Fotografen nicht direkt anschaut. Wurde das Foto vielleicht am Hochzeitstag von Fred Stein aufgenommen[16]?

1937

Am 15. Juni bewarb sich Léo als Französisch-, Gesang- und Hebräischlehrer an der Alliance Israélite Universelle[17]. Er hoffte darauf, zu seiner Familie nach Palästina zurückzukehren.

In der Bewerbung befanden sich ein Lebenslauf, sowie Empfehlungsschreiben des E.I.F., des Kirchenamtes und der Realschule in Hamburg. Hatte er eine Absage bekommen oder entschied er sich doch in Frankreich zu bleiben?

1938

Zwei Dekrete vom 2. Mai und 12. November 1938 erzwangen, dass Ausländer unter Hausarrest gestellt wurden, woraus später eine sogenannte Verwaltungsinternierung wurde. Die Gründe für diese Maßnahme wurden in den Dekreten klar dargelegt: Diese Dekrete markierten eine diskriminierende Einteilung in moralisch zweifelhafte Personen, die der Aufnahme im Gastland nicht würdig sind und dem gesunden, hart arbeitenden Teil der ausländischen Bevölkerung.

In einem Brief vom 10. Januar 1938 des Präsidenten der Israelischen Gemeinde des Niederrheins erfährt man, dass Shimon Hammel, der ehemalige Präsident der Jugend des EIF, nach Straßburg gekommen war, um eine Empfehlung für Léo als Lehrer auszusprechen.

Der Consistoire spricht sich zunächst gegen Léos Anstellung aus, da die Stelle nicht an einen Ausländer gehen dürfe, aber an einen guten Lehrer[18]. Dennoch, wird aus einem Brief an den Präsidenten der Israelischen Gemeinde Niederrhein, datiert am 31. Mai 1938, deutlich, dass Leo doch schließlich angestellt wurde.

In diesem Brief schlägt Léo ein Freizeitprogramm für das Jugendzentrum Villa Haas vor, das bald für die jungen Straßburger geöffnet werden sollte. Dieses Programm wird schließlich veröffentlicht, sein Vorschlag wird also umgesetzt[20].

Im Mai 1938 sind Léo und Rachel in Straßburg. Rachel erneuerte ihren Ausweis am 23. Mai und bekam ihn am 24. Juni zurück[21].

Am 20. September schrieb Léo an die Präfektur Niederhein um deutlich zu machen, dass er bereit sei um in die französische Armee zu gehen, sofern eine Genrealmobilmachung notwendig sein würde. (Zitat Anfrage Eintritt in frz. Armee[22]).

Noémi wurde am 27. Oktober 1938 geboren. Das Ehepaar lebte zu der Zeit in Zürich [23]. Schon am 28.Oktober, schreib Léo dem Präsidenten der Israelischen Gemeinde[24] um die Geburt seiner Tochter in der Klinik Adassa zu verkünden. Im November stellt Léo Cohn die erste Anfrage auf Einbürgerung in Straßburg[25].

1939

Nach der Invasion in Polen durch die Deutschen am 1. September 1939, erklärten Frankreich und Großbritannien Deutschland am 3. September den Krieg.

520 000 Franzosen wurden aus den Grenzgebieten zwischen Maginot Linie und Deutschland evaquiert. Am 2. September 1939 lässt die französische Regierung Straßburg über das Périgueux, Brantôme, Hautefort evaquieren…

Zunächst versuchte Léo ins Périgueux zu gelangen. Dafür bat er mehrere Personen, ihm ein Empfehlungsschreiben auszustellen. Außerdem stellte er einen zweiten Antrag auf Einbürgerung[26]. Es wurden mehrere Schreiben für Léo ausgestellt, war das der Grund für die Antragstellung der Einbürgerung? Oder um das Périgueux zu erreichen? Das erste Datum, der 25. September 1939(Isaïe Schwartz, Rabbiner Frankreichs), es folgten weitere am 24.November 1939 (Ernest Weill, Rabbiner von Colmar und dem Niederrhein), 1. November 1939(Isaïe Schwartz), 27.Dezember 1939(Joseph Weill)[27].

Da sie keine Erlaubnis bekamen, ins Périgueux zu gehen, ließen sich Léo, Rachel und Noémi in Gérardmer nieder, wo es auch ein Jugendzentrum des E.I.F. gab. Sie wohnten bei sehr höflichen Leuten[28]. Noémi besuchte die Schule der sœurs de Notre dame de Sion.

Die Evaquierung spielte sich sehr rasch ab und jeder durfte nur 30 kg Gepäck mitnehmen. Im Oktober fragte Léo Madame Einstein, ob er einige Bücher und persönliche Sachen aus seiner Wohnung hohlen dürfte [29].

3- Gemalter Grundrissplan der Wohnung in Straßburg von Léo, Familien Archive, Noémi Cassuto

Diese Pläne zeigen ein kleines Apartment mit der Zimmern: Büro, Wohnzimmer, Schlafzimmer und Badezimmer. Er bildet auch die Bibliothek im Arbeits- und Wohnzimmer ab. Dort findet man alles, was ihn als Kind geprägt hat: Werke auf französisch, deutsch und englisch (Philosophie, Literatur, Geschichte , Wissenschaft, Religion). Ein Bereich widmet sich nur der Musik(Beethoven, Brahms…).

Um eine Internierung zu vermeiden, versuchte Léo, sich in die Légion einzugliedern, um die Region verlassen zu können[30]

Am 1. September 1939, zwei Tage vor Kriegserklärung, wurde ein Dekret veröffentlicht, dass im Falle eines Konfliktes, die Versammlung aller Männer zwischen 17 und 50 Jahren vorsah. 4 Tage später, wurden sie durch ein Schreiben aufgefordert, sich zu den Sammelstellen zu begeben. Am 14. September, wurden die 50-60 jährigen Männer zur Internierung vorgeladen.

Die Fremdenlegion war eine Möglichkeit, der Internierung zu entgehen. Aber das Militär konnte durch setzten, dass diese neuen Legionäre nicht auf dem Territorium der Großstadt kämpfen durften, und der Generalstab widersetzte sich dem Engagement der Deutschen gegen Deutschland “aus Gründen des Völkerrechts und der Sitte”. Sie wurden deshalb nach Nordafrika verlegt[31].

Am 15. Dezember 1939, wenige Tage vor seiner Abreise, schrieb Léo an seine Familie aus Gérardmer. Der Brief ist auf Französisch. Er spricht liebevoll und mit Humor von der kleinen Noémi. Er erwähnt auch seine bevorstehende Abreise für die Legion und seine mögliche Entsendung nach Afrika oder Syrien und seine Vorliebe für das letztere Ziel[32].

Am 26. Dezember wurde er für die Dauer des Krieges in die Legion [33] eingegliedert (Rekrutierung für das Militärkommissariat in Épinal). Er trat in das erste ausländische Infanterieregiment mit der Regimentsnummer 91385 [34] ein. Er wurde nach Algerien nach Sidi Bel-Abbès geschickt, wo er am 31. Januar ankam [35].

4- Léo als Legionär, Familienarchive Noémi Cassuto

Léo und Rachel kommunizierten über Briefe. Auch mit der kleinen Noémi hatte er engen Kontakt, die ihm über ihre Mutter schreibt[36].

Im Mai schrieb Rachel an die Präfektur der Vogesen, um herauszufinden, ob der Einbürgerungsantrag von Léo tatsächlich nach Paris übermittelt worden war [37].Man sagte ihr, dass gegen die Akte ermittelt werde.

Vichy-Dekret über die Revision von Einbürgerungen.

Es wurde beschlossen, dass alle erworbenen französischen Staatsbürgerschaften seit der Verkündung des Staatsangehörigkeitsgesetzes vom 10. August 1927 überprüft werden sollten. Insgesamt sollen fast 7.000 Juden offiziell ausgebürgert werden.

Nach dem Debakel wurde die Legion nicht demobilisiert. Die Einheit von Léo wird zum Stützpunkt Sidi-Bel-Abbès zurückgebracht.

Am 14. August schreibt Léo an seine Eltern aus Sidi-bel-Abbès und vor allem an seine Mutter zu ihrem Geburtstag. Er schrieb diesen Brief auf Französisch. Léo erzählt über sein Leben in Sidi-bel-Abbès, in einer “privilegierten” Gesellschaft von Musikern. Léo ist selbst ein “Fünferschüler”, ein Instrument, das sich sehr von seinem “lieben alten Pipeau” unterscheidet, das er mit einer Flöte vergleicht. Ein Memo von Generalmajor Beznet vom 14. November belegt, dass Léo seine Freiheit wiedererlangt hat. Er kehrte im Dezember 1940 von der Legion zurück [38] und ging nach Moissac, um sich Rachel und Noémi anzuschließen.

4.Oktober: Ein antisemitisches und fremdenfeindliches Gesetz, das ausländische Juden der Polizeiwillkür ausliefert, indem es den Präfekten die Macht überträgt, “Ausländer jüdischer Rasse” in Sonderlagern zu internieren.

Art. 1 – Ausländische Staatsangehörige jüdischer Rasse werden ab dem Datum der Verkündung des vorliegenden Gesetzes auf Beschluss des Präfekten des Departements, in dem sie ihren Wohnsitz haben, in Sonderlagern interniert.

Art. 3 – Ausländische Staatsangehörige der jüdischen Rasse können jederzeit vom Präfekten des Departements, in dem sie ihren Wohnsitz haben, zum Zwangsaufenthalt zugewiesen werden.

1941

Die offiziellen Vichy-Texte geben wieder, was für Juden verboten war. Es wird jedoch auch deutlich, dass das nicht auf alle Bereiche zutrifft. Zum Beispiel die landwirtschaftlichen Berufe fehlen auf der Liste der Berufsverbote. Aus diesem Grund entwickelten jüdische Vereinigungen wie die E.I. die Berufsausbildung im Zusammenhang mit ländlichen Aktivitäten, teilweise mit Unterstützung von Vichy. Das Thema der Rückkehr in das Land wurde bereits vor dem Krieg von Robert Gamzon befürwortet und entsprach damals dem, was Vichy fördern wollte. Das erste Zentrum wird in der Gemeinde Lautrec mit etwa vierzig jungen Menschen zwischen 16 und 25 Jahren eingerichtet. Das zweite in Taluyers (Rhône) und das dritte in Viarose (Tarn et Garonne). Diesen Zentren gelingt es, eine feste Existenz aufrechtzuerhalten, eine jüdische Erziehung umzusetzen und von der Bevölkerung allgemein akzeptiert zu werden [39].

Am 22. Januar 1941 ließen sich Léo und Rachel in Lautrec[40] nieder, einer kleinen Gemeinde, die etwa fünfzehn Kilometer von Castres entfernt liegt.

Lautrec ist eine ländliche Gemeinde, die im November 1940 gegründet wurde. Das Gebiet umfasste mehrere Bauernhöfe, Handwerksbetriebe und ein Studienzentrum. Eine erste Gruppe zog am 11. November 40 auf den Bauernhof von Grasse, und wenig später richtete ein Team in den Nebengebäuden des Château de Lautrec die Räumlichkeiten des so genannten “le chantier rural de Lautrec” ein. Lautrec war ein ziemlich großes Anwesen in schlechtem Zustand, aber die Nebengebäude des Schlosses konnten etwa vierzig junge Leute beherbergen. Der 2 km entfernte Bauernhof von La Grasse, wo die Gruppe der E.I.F. als Teilpächter tätig war, waren die “Défricheurs” [41].

Sie wohnten im Erdgeschoss des Maison d’Estampes, einem alten Haus aus dem 17. Jahrhundert ohne viel Komfort. Es gab Strom, aber kein fließendes Wasser. Sie mussten Wasser aus einem Brunnen schöpfen, der sich hundert Meter vom Haus entfernt befand. Léo zeigte den Kindern, Wasser mit einem Eimer zu schöpfen. Kleine Holzöfen heizten jeden Raum [42]. In diesem Haus befanden sich auch die Gamzons (Robert, seine Frau, der Specht und seine beiden Kinder) sowie das Ehepaar Pulver und ihre Zwillinge.

Im November beantragte Léo eine Zulage beim Flüchtlingsdienst des Departements Tarn. Er sagt, dass er als “landwirtschaftlicher Lehrling” im ländlichen Workcamp Lautrec arbeitet, und erklärte, dass er kein Gehalt, sondern eine Zulage vom ländlichen Workcamp erhalte. Er gab an, dass er vor seiner Evakuierung Student war. Der Bürgermeister von Lautrec hatte jedoch eine ablehnende Stellungnahme zu diesem Antrag mit dem Motiv “Landwirt im Alter von 28 Jahren: kann in diesem Alter selbstständig sein. Die Kinder, die von der Flüchtlingshilfe profitieren” [43]. abgegeben

Am 15. April 1941 erhielt Léo Cohn einen auf Lautrec ausgestellten Ausländerausweis Nr. 0018, der bis zum 9. März 1942 gültig war [44].

Léo kreierte Sois Chic le journal. Es handelt sich dabei um eine Wandzeitung des E.I.F für die Défricheurs de Lautrec, ab Dezember 1941 gab es auch eine Version, die an alle E.I.F.-Zentren verschickt wurde. Die Veröffentlichung blieb unregelmäßig [45], weil Léo keine Mitarbeiter hatte. Er bedauerte dies in der Dezember-Ausgabe 1941: “Jeder hat das Sagen, jeder kann mitmachen, jeder muss sich für ‘Be-Chic’ verantwortlich fühlen. Diese Publikation wird dann ein getreuer Spiegel der Seele der Baustelle sein. Seien Sie hübsch vor diesem Spiegel, seien Sie elegant, seien Sie “chic”! “Der Inhalt der Zeitung ist sehr abwechslungsreich, wir können einen Schwerpunkt auf Lämmer, Geschichten oder sogar einen Artikel über das Judentum im Workcamp machen…“

In Lautrec und in den anderen ländlichen Zentren oder Kinderheimen der E.I.F. konnte Léo seine Talente als Lehrer und Chorleiter ausüben. Leo lehrte Hebräisch[46], er war auch einer der Leiter der Ausbildungskurse für die I.F.E.-Leiter, aber auch ein spiritueller Leiter. Im Herzen war er ein Lehrer. Unabhängig davon, ob es sich um ein Kind oder einen Erwachsenen handelte, und unabhängig von seinem intellektuellen Niveau[47], hatte er den Wunsch, nicht nur sein Wissen, sondern vielmehr eine Lebensphilosophie weiterzugeben und zu teilen. Dieses Bestreben nach Weitergabe entstand, als er noch sehr jung war, wie einer seiner Lehrer, der Arzt von Joseph Jacobsen, der Lehrer von Leo Cohn an der Talmud-Tora-Schule, erwähnt [48].

5- Gruppe junger Leute, die vor dem Schloss Lautrec unter Aufsicht von Leo arbeiten, Fonds Mémorial de la Shoah, MI_392a

6- Leo als Beamter, Holocaust-Gedenkfonds, MXXXVa_6

Musik und Gesang waren wesentlich für Léo, davon war er überzeugt, für die Gemeinschaft der “Pioniere”, die er leitete. Singen hilft, die Gemeinschaft in Freude und Brüderlichkeit zu vereinen; es ist auch eine Art, ein freudigeres Judentum zu leben, eine notwendige Ergänzung zur harten Arbeit auf dem Land im ländlichen Arbeitslager von Lautrec.

1942

Vom 15. Bis zum 23. Januar, ging der Chor du chantier rural de Lautrec, den Léo leitete, auf Tournee.

Um sich fortzubewegen, erhielt Leo von Robert Gamzon einen Passierschein für sicheres Geleit. Tatsächlich konnten die Präfekten seit den antisemitischen Gesetzen vom Oktober 1940, ausländische Juden unter Zwangshausarrest stellen. Dies war der Fall bei Leo. Am 18. Januar trat der Chor um 15 Uhr in Marseille im “Temple israélite”, rue de Breteuil auf [49].In dem kleinen Büchlein, das an die Zuschauer verteilt wurde, steht, dass sich unter den Sopranistinnen Rachel befindet, die als “Mutter der Druckgrafik” bezeichnet wird. Die Chorsänger kommen aus verschiedenen Orten, nicht nur aus Lautrec… Das Repertoire ist vielfältig: klassische Stücke (Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Haëndel), Synagogengesänge, aber auch populäre französische, palästinensische und jüdische Lieder.

Der Chor wurde sehr geschätzt, wie Léo in der Februar-Ausgabe von Sois-Chic 1942 schrieb 50]” Dennoch wird der von Leo gewählte Weg in Lautrec manchmal kritisiert.

Im April schrieb er an einen Mann namens Lucien, mit dem er einen Streit über Fragen der Religionsausübung hatte. Das Dokument [51] ist ein mit Bleistift geschriebener Entwurf, vielleicht wurde er nicht abgeschickt? In diesem Brief bringt er seine tiefe Uneinigkeit mit Lucien zum Ausdruck, den er als “orthodox” bezeichnet, er wirft ihm oberflächliche, unbegründete Erklärungen und sogar seine Unverschämtheit und Anmaßung vor. Er antwortet offensichtlich auf einen Brief, den er erhalten hat und in dem Lucien ihm seine Wut und seinen aggressiven Tonfall vorwirft. Die Diskussionen könnten in Lautrec sehr lebhaft sein. Leos Einführung des “Neo-Chassidismus” wird nicht von allen akzeptiert, ob sie nun “orthodox” sind oder sich im Gegenteil weigern, religiöse Riten zu praktizieren.

Am 1. Mai schreibt Leo an Chameau[52] und verweist erneut auf die internen Konflikte zwischen den Führungskräften von E.I. Leo bedauert, dass die Jugendlichen des Workcamps den Schabbat nicht respektieren. Er bedauert, dass er den Auftrag, den ihm Robert Gamzon erteilt hatte, “das Judentum wieder an das Landleben anzupassen”, nicht erfüllen konnte. Im gleichen Brief beschreibt Leo mit großer Freude über die “Heldentaten” von Naomi und Ariel. Eine ganze Seite ist ihnen gewidmet, und man kann dort die ganze Liebe und Bewunderung eines Vaters für seine Kinder sehen.

7- Noémi, Rachel, Léo und Ariel, Familienarchive, Noémi cassuto

Léo unternahm viele Reisen zwischen den verschiedenen Zentren des I.E., vor allem im Sommer, während der Zeit der großen landwirtschaftlichen Arbeiten, in der die Défricheurs sich nicht mit Studien oder Diskussionen über Gelder beschäftigen konnten: “Vom 1. bis 12. Juni werde ich mit Loinger im Kinderheim Montintin [O.S.E. Kinderheim] campen, ich werde die Gelegenheit nutzen, einen Zwischenstopp in Périgueux einzulegen, wo sie eine Oneg-Coco für den 13. vorbereiten. Danach werde ich, wenn meine Papiere es erlauben, Beaulieu [E.I. Children’s Home] einen Besuch abstatten. Vom 19. bis 29. Juli muss ich mit den Lastwagenfahrern zelten. Vom 27. August bis zum 7. September werde ich nach Montserval [E.I.F.-Schulcamp] fahren. Am oder um den 12. August heiratet Musa in Haute Savoie. Wenn ich dorthin gehen muss, würde ich gerne einige Zeit in einem echten Trainingskurs bei Ihnen vor Ort verbringen. (…) Das einzig Unangenehme an all diesen Reisen ist, Rachel während dieser Zeit allein zu lassen. Aber Rachel selbst ist glücklich, mich wieder in der “Welt” zu sehen” [53](original Zitat auf Französisch).

Am 25. August erfuhr Robert Gamzon in Vichy, dass in der Südzone eine Razzia stattfinden sollte. Am 26. August 1942 berief er in Moissac ein Treffen der Leiter des I.E. ein. Dies war die Geburtsstunde der illegalen Bewegung: la sixème [54].

1943

Angesichts der wachsenden Gefahr beschloss die Gemeinschaft des I.E. 1943, alle ihre Zentren aufzulösen un zu verteilen. Léo, Rachel und die beiden Kinder ließen sich in einem kleinen Haus in der Gemeinde Labessonnié nieder, an einem Ort namens La Caroussinié, 4 km vom Dorf Lautrec entfernt. Sie nahmen den Namen Colin an. Wir kennen die falschen Papiere von Léo dank der Geburtsurkunde von Aviva, in der er angibt, dass sein Name Léon Bernard Colin ist, geboren in Bourbach am Oberrhein, Rachel heißt Renée Schmitt, geboren in Bischwiller am Niederrhein.

Rachel dokumentierte ihr Leben im Verborgenen: “Wir verließen Lautrec 1943 für den Maquis. Um die Wahrheit zu sagen, es war kein organisierter Maquis. Wir gingen in ein kleines Haus, das die Familie von Toulouse-Lautrec dem I.E. zur Verfügung gestellt hatte (…) In diesem kleinen Haus lebten wir anderthalb Jahre lang, und wir nahmen dort junge Leute auf. Wir waren sogar acht oder zehn Personen in diesem Haus, und wir lebten wirklich ein bäuerliches Leben, was uns nicht daran hinderte, ein aktives spirituelles Leben zu führen. Abends, mit dem Feuer im Kamin, lesen wir französische Klassiker. Wir haben für Adventisten bestanden, eine Sekte, die den Sabbat feiert. Wir hatten falsche Papiere auf Colins Namen, ebenso wie unsere beiden Kinder. Was meine Tochter betrifft, die im März 1944 geboren wurde, so hatte sie vom Moment ihrer Geburt an eine “wirklich falsche Karte”, und als wir in Israel ankamen, hatten wir große Schwierigkeiten zu beweisen, dass sie tatsächlich unsere Tochter war…Wir haben “Be Chic” herausgegeben. Wir standen in Kontakt mit allen Chefs der Sechsten und insbesondere mit Hammel, der unter der Schirmherrschaft der E.I.F. für die Organisation von Kinderbesuchen in der Schweiz zuständig war [55]”( original Zitat in Franzöisch).

Am 18. September erließ die Polizeipräfektur Tarn einen Durchsuchungsbefehl, weil Léo Cohn “die Gemeinde, in der er unter Hausarrest stand, ohne Genehmigung verlassen hat”, und er sollte “in guter Begleitung von Muret[56] in das Lager Noahs geführt werden”.

Der Übergang zur militärischen Option des sechsten EIF erfolgte in zwei Phasen. Am 16. Dezember 1943 bildete eine Gruppe von 8 Kadern und Jungbauern in einem verlassenen Bauernhof, La Malquière, einer verlorenen Ecke von Sidobre im Lacaune-Gebirge, östlich von Vabre (Tarn), eine Macchia. Am 29. April 1944 schuf dann eine ähnliche Gruppe, ebenfalls aus Lautrec, die jetzt geschlossen ist, ebenfalls eine Macchia in den Ruinen eines Bauernhofs, Lacado, 7 km von La Malquière entfernt. Die FFI-Führer von Vabre machten La Malquière zum militärischen Ausbildungszentrum für lokale Kämpfer [57].

Shimon Hammel erinnert sich an dieses Geheimtreffen: “Bouli (Simon) und ich erhielten den Befehl, in die Montagne noire in der Nähe von Castres zu gehen. Wir sollten Leo Cohn und andere Häuptlinge und Älteste in einer Holzfällerhütte finden, und dort sollten wir die spirituellen Grundlagen für ein jüdisches Buschland legen. Es ist eine meiner bewegend sten Erinnerungen. Wir hatten symbolisch die Ernennung von Gamzon zum Hauptmann, Gilbert Bloch zum Leutnant sowie Roger Kahn und Adrien Gainsburger als Leutnants des jüdischen Busches in der Tasche. Ich, der meine militärischen Qualitäten nie über den Rang eines Unteroffiziers hinaus schob, musste einen Hauptmann und drei Leutnants ernennen. Wir kamen bei Einbruch der Nacht in dieser Holzhütte mitten im Wald an, es war sehr kalt. Wir hatten eine große philosophische Diskussion über ein jüdisches Thema, das von Leo beherrscht wurde. Sie dauerte bis halb Mitternacht. Dann baten wir Roger Kahn und Adrien Gainsburger, herauszukommen, und im Mondlicht, im Frost des Waldes, machten wir sie beide zu Leutnants des Maquis. Das ist eine meiner bewegendsten Erinnerungen. Diese militärische Zeremonie im Wald und in der Stille der Nacht, mit Juden, die immer friedlich gewesen waren … ” (original in französicher Sprache)[58].

1944

Am 2. März 1944 wurde Aviva in Castres, rue de la Tolosane unter dem Namen Yvette Colin [59] geboren. Noémi und Ariel erinnern sich, dass sie am Vortag in der Kälte einen sehr langen Weg zurückgelegt hatten, um von dem Haus, in dem sie sich versteckt hatten, in die Stadt Castres zu gelangen.

In einem Brief an Hardy vom April 1944 [60] seine bevorstehende Abreise mit einer Gruppe junger Leute und bittet ihn um ein Treffen am 3. Mai in Lyon[61]. Das Treffen in Lyon konnte nicht stattfinden, Hardys Antwort kam zu spät [62].

Am 7. Mai fuhr Léo Rachel und ihre drei Kinder an die Schweizer Grenze bei Annemasse. Die Grenzüberquerung verzögerte sich um einen Tag, weil Léo und Ariel am Morgen beteten und die Familie so den Zug verpasste, der sie nach Annemasse bringen sollte. Dieses Gebet rettete ihnen das Leben, denn der Zug wurde kontrolliert und alle Juden wurden verhaftet. Marianne Cohn [63] brachte sie über die Grenze, und Leo übertrug ihr nach einem letzten Abschied die Verantwortung über seine Familie an. Noemi erinnerte sich an diesen letzten Moment, als die Familie noch zusammen war. Man musste sich beeilen, um zwischen zwei deutschen Patrouillen, die die Grenze bewachten, hindurchzukommen. Aber Leo nahm sich die Zeit, seine Kinder zu segnen, und versprach ihnen ein Wiedersehen in Palästina. Die Gruppe entfernte sich, und als Noemi sich ein letztes Mal umdrehte, sieht sie, wie ihr Vater ihr ein letztes Mal zuwinkt. Um unter den Stacheldraht zu gelangen, wurden Noemi und Ariel in eine Decke gewickelt. Jedes Kind ging einzeln. Ariel erinnert sich an die Wache und sein Gewehr und die Angst, die er fühlte.

Zurück in dem kleinen Haus schrieb Leo am 11. Mai seinen ersten Brief an Rachel. Er freue sich riesig auf ein Wiedersehen[64]. Er fragt nach Neuigkeiten über die kleine Aviva und gibt Rachel sogar Ratschläge, wie sie sie füttern soll: Sie solle weiterhin stillen und zu einem Löffel Milch ab dem dritten Monat Orangensaft hinzufügen. In diesem Brief erklärt Léo auch seine letzten Vorbereitungen, seine letzten Treffen, er präzisiert, dass er definitiv am Montag, d.h. am 15. Mai, abreisen wird.

Léo wurde am 17. Mai 1944 zusammen mit Jacques Roitman [65], Hermann-Hubert Pachtmann [66] und drei weiteren Widerstandskämpfern auf dem Bahnhof Saint Cyprien bei Toulouse verhaftet. Rachel glaubt, er sei denunziert worden [67]. Léo sollte einige junge Leute nach Spanien bringen, er wurde verhaftet, als er gerade in den Zug einsteigen wollte. Er hat gerade genug Zeit, das Blatt herunter zu schlucken, auf dem die Namen der Jugendlichen stehen.

Abraham Block war Zeuge dieser Verhaftung. Er war es, der die Jugendlichen nach Spanien und im Oktober 1944 dann nach Palästina bringt [68]. Er wurde zunächst zusammen mit Jacques Roitman im Gefängnis Saint Michel in Toulouse inhaftiert. Robert Gamzon versuchte, ihm eine Nachricht zukommen zu lassen, um herauszufinden, ob er als Widerstandskämpfer oder als Jude verhaftet worden war. Elsa Baron wurde mit dieser Mission beauftragt, aber sie war nicht erfolgreich [69].

Leo wird zunächst als Widerstandskämpfer nach Compiègne [70] geschickt. Er traf am 6. Juli in Drancy ein und war unter der Nummer 24895 registriert.

Léo schreibt seine letzten Briefe an Rachel, seine Kinder und seine Freunde. Seine Briefe werden aus Drancy herausgeschmuggelt. Ist es der Lagerarzt, der sie herausholt, wie Ariel meint? Oder ein Netzwerk von Widerstandskämpfern innerhalb des Lagers, wie Aviva glaubt, nach dem, was Rachel ihr erzählt hat? Vielleicht beides. Er fragt nach seinen Kindern, auch nach dem Gesundheitszustand der kleinen Aviva. Er sagt, er sei in guter körperlicher Verfassung.

Er verließ das Lager [71], um sich um die Kinder zu kümmern und mit ihnen zu spielen: “Ich fahre in eine unbekannte Richtung, und in dem Konvoi sind 300 Kinder! Man kann sich nicht über ihre Behandlung beklagen, aber was für ein Elend, so viele von ihnen zu sehen, die weder Vater noch Mutter kennen, die sich nicht an ihre Namen erinnern! Ich spiele oft mit diesen Kindern, ich verließ das Lager, um sie in ihren Wagen zu begleiten, aber es war unmöglich[72] “( original in Französich).

Zwischen dem 21. und 25. Juli 1944 führte eine Razzia in den Häusern der UGIF in der Pariser Region zur Verhaftung von 250 Kindern und 33 Mitarbeitern. Sie wurden alle im Konvoi 77 deportiert, darunter 330 Kinder unter 18 Jahren.

Er organisierte einen Chor, jedoch kamen und gingen die Mitglieder ständig, sodass eine Arbeit schwierig war[73]. Nach dem Krieg fotografierte Shimon Hammel ein Graffiti[74] von Léo, die letzte Spur, die Léo hinterlassen hat und die nun verschwunden ist. Léo blieb tief religiös, und bis zum Ende praktiziert er den seinen Glauben[75]. Auch in der Zeit kurz vor dem Abtransport.

Léo wurde am 31. Juli 1944 vom Konvoi 77 deportiert, und in dem Wagen organisierte er einen letzten Chor mit jungen Frauen. Diejenigen, die überlebt haben, erzählten, wie er sie ermutigte, zusammen zu bleiben und so laut wie möglich zu singen, um der Gruppe Kraft zu geben. In Buchenwald hatte man ihnen den Spitznamen “die Französinnen, die singen” [76] gegeben. In den schwierigsten Momenten, in Drancy mit all den Waisenkindern, in dem Wagen, der ihn nach Auschwitz bringen sollte, findet Léo die Kraft, einen Chor zu leiten, um ein wenig Wärme in seine Umgebung zu bringen.

Er gehört zu denjenigen, die im Lager zunächst arbeiten mussten. Nach seiner Deportation in das Lager Echterdingen starb er am 28. Dezember 1944 an Erschöpfung.

Bei der Durchsuchung der Archive fanden wir einen Brief von Robert Weil, in dem er die letzten Momente beschreibt, die er mit Leo in Auschwitz verbracht hat. Sie überwältigte uns alle mit ihrer Genauigkeit, und mit diesem Auszug möchten wir schließen: “Ich habe versucht, Leo davon zu überzeugen, die Dinge von einem rationalen Standpunkt aus zu sehen, das war damals meine Illusion. Seitdem habe ich mich verändert. … Die Wirklichkeit ist nur Schein, sie hängt von den Strukturen der Ansätze ab. …] Man muss seine eigene Transzendenz erkennen.

Ich war damals jung, mit einer kartesianischen Ausbildung. Leo hatte mehr Kontakt mit der Welt des imaginären Musiker- und Dichterdaseins, und er stand dem Mystischen nahe, den “Meistern”, die von Gott betrunken waren[77](wörtlich übersetzt).

Références

[1] Archive de l’école Talmud Torah, Hambourg.

[2] Témoignage de son frère ainé Haïm Cohn extrait du livre de Judith Bar-Chen, Léo 1913-1945, éditions du Ministère de la Défense, Israel ISBN 965-05-0592-X.

[3] Témoignage de Léo Cohn dans le CV qu’il a rédigé en 1937, archives familiales Noémi Cassuto.

[4] “ Internally, you could feel that it was someone who was deep, who radiated. (…). He was someone who had a very deep spiritual life, something that was reflected in his personality” oral testimony of Lia Rosenberg; Robert Gamzon’s daughter, wo lived at Lautrec with Léo Cohn when she was 10 to 12 years old.

[5] Extrait d’une lettre de Robert Weill adressée à Frédéric Chimon Hammel, in Souviens toi d’Amalek, p. 309

[6] Les parents de Léo, peu favorables à la liaison amoureuse qu’il entretient avec Rachel Schloss souhaitent éloigner Léo. (témoignage d’Aviva Geva, fille de Léo Cohn).

[7] CV page 1, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[8] Attestation d’une demande de régularisation, archives de Pierrefitte, dossier cote n°19940505/1679.

[9] En 1923, Robert Gamzon crée la première patrouille scoute de France. En janvier 1927, le mouvement prend le nom d’E.I.F. (Éclaireurs Israélites de France), il intègre officiellement le scoutisme français en 1938.

[10] « Notre Cité » est un foyer créé 38 rue Vital à Paris par Robert Gamzon à Paris pour accueillir des membres des E.I.F.

[11] Clan de routiers : dans le scoutisme cela désigne la branche ainée qui regroupe des jeunes de 18 à 25 ans. Prolongement du scoutisme destiné à des jeunes trop âgés pour être éclaireurs.

[12] Témoignage Frédéric Hammel, Souviens toi d’Amalek p.278-79)

[13] Archives municipales, Paris, État civil mairie du 16ème arrondissement, acte n°189.

[14] Précision de Léo dans son CV page 2, archives familiales Noémi Cassuto.

[15] Archives familiales Noémi Cassuto, photo des studios Stein 1936.

[16] Fred Stein né à Dresde en 1909, s’installe à Paris et ouvre son premier studio dans son appartement en 1933. Il fait partie d’un groupe d’intellectuels et artistes émigrés. Ils fréquentent notamment Gerda Taro et Robert Capa.

[17] Lettre écrite par Léo Cohn datée du 15 juin 1937, archives familiales Noémi Cassuto.

[18] Dans cette lettre, le Consistoire fait part au président de la communauté israélite qu’il ne soutient pas le choix de Léo Cohn en tant qu’éducateur de la jeunesse car il est étranger, de nationalité allemande, procès-verbaux des actes du Consistoire israélite du Bas Rhin, archives du Bas Rhin cote n° 2237 W 1.

[19] Archives du Bas Rhin, cote n° 2237 W 43/1.

[20] Archives du Bas Rhin, cote n° 2237 W 43/1.

[21] Archives de Pierrefitte, dossier cote n°19940505/1679.

[22] Copie d’une lettre de Léo Cohn, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[23] Registre des naissances de la ville de Strasbourg, acte n°4359, cote 4E82/1065

[24] Archives du Bas Rhin, cote n°2237 W 43/1

[25] Une lettre cosignée d’Edmond Fleg ,de Robert Gamzon, du grand rabbin délégué du Consistoire central et du président du Consistoire israélite de Paris datée du 30 novembre 1938 et adressée au Préfet du Bas Rhin vient appuyer la demande de Léo Cohn, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[26] Une lettre de Rachel –du 2 mai 1940- et un certificat du maire de Gérardmer attestent de cette deuxième demande de naturalisation adressée à la préfecture des Vosges en décembre 1939, archives Mémorial de la Shoah, Fonds E.I.F., correspondance Rachel.

[27] Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[28] Lettre de Léo à ses parents, 15 décembre 1939, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[29] Léo Cohn a écrit deux autorisations à pénétrer dans son appartement, elles sont visées du maire de Gérardmer et datées du 10 octobre et 15 décembre. Deux plans accompagnent ces lettres, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[30] Lettre de Léo datée du 15 décembre 1939, Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[31] Denis Peschanski, La France des camps, Gallimard, 2013, p. 76-78

[32] Lettre de Léo à ses parents, 15 décembre 1939, Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[33] Copie de l’acte d’engagement, Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[34] Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[35] La date de son arrivée est précisée dans une lettre du colonel Girard commandant du premier régiment Étranger, Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[36] Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[37] Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[38] Pour Rachel, Léo est rentré au moi de septembre, c’est ce qu’elle dit à Annie Latour témoignage de Rachel, fonds Annie Latour, DLXI-20, archives Mémorial de la Shoah), mais en fait une note de service émanant du général de division Beznet, atteste que Léo était encore à Boghar, interné au camp de Suzzoni, le 14 novembre 1944. Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[39] Jacques Sémelin, Persécutions et entraides dans la France occupée, Comment 75% des Juifs en France ont échappé à la mort, p. 257, 269-70)

[40] Fonds de la Préfecture du Tarn, notice individuelle cote n°506 W 171.

[41] Témoignage de Denise Gamzon sur le site : http://judaisme.sdv.fr/perso/pivert/guerre/lautrec.htm

[42] Témoignage Denise Gamzon, id.

[43] Archives Préfecture du Tarn, cote n° 348 W 393.

[44] Fonds de la Préfecture du Tarn, notice individuelle cote n°506 W 171.

[45] Le précédent numéro est paru trois mois avant, Sois Chic, décembre 1941.

[46] Dans une lettre d’août 1942 destinée à Fourmi – Totem de Jeanne Hammel- qui dirige le centre de Taluyers, Léo lui apprend des mots d’hébreu et répond à ses questions au sujet l’organisation d’un centre de jeunes filles (les tâches à accomplir, les responsabilités de chacune en fonction de leur âge…).

[47] “He was, I don’t know how you say it in French, in Hebrew you say “he spoke to people at eye level”, he didn’t look down on people even though he was very tall, he gave importance to the person he was talking to, it could be his daughter who was three years old or me who was ten, it could be anyone, it could be face to face, as an equal.” Oral testimony of Lia Rosenberg, Robert Gamzon’s daughter, who lived at Lautrec.

[48] Lettre du professeur dans laquelle Jospeh Jacobsen il atteste des qualités humaines et relationnelles de Léo, de ses « dons » pédagogiques, de sa « dévotion » au judaïsme et son amour pour la musique, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[49] Invitation pour assister à cette chorale, archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[50] Sois-Chic, Journal mural de Lautrec, février 1942

[51] Archives familiales, Noémi Cassuto.

[52] Totem de Shimon Hammel, durant l’été 1941 il a ouvert avec sa femme Jeanne Hammel ont ouvert un centre agricole à Taluyers (Rhône) pour sauver des jeunes garçons et filles juifs.

[53] Cité dans Témoignage Frédéric Hammel, Souviens toi d’Amalek p. 300-301

[54] Ce nom provient de la section qu’intègre les E.I.F au sein de l’UGIF après leur interdiction par le régime de Vichy. Ils intègrent la sixième section de la Direction Jeunesse.

[55] Témoignage de Rachel archives Mémorial de la Shoah, fonds Anny Latour, DLXI-20.

[56] Archives de Pierrefitte, cote 19940505/1679.

[57] In La Sixième EIF source historiques ARJF-OJC Résistance/sauvetage, France 1940-1945, p. 248.

[58] Témoignage de Shimon Hammel, Archive Mémorial de la Shoah, cote DLXI-38.

[59] Acte de naissance d’Aviva, archives état civil de de Castres.

[60] Antoinette Lublin (dite Augustine Hardy, Tony). A partir de janvier 44 elle effectue des voyages de coordination entre le comité directeur de l’Armée juive de Toulouse et celui de Lyon, les groupes francs de ces villes et celui de Paris. Elle transporte des fonds et des armes entre ces trois villes. In Organisation juive de combat, Résistance sauvetage, France 1940-1945, Éd Autrement, pp 89-90.