Liki BORNSZTAJN (Borensztajn)

Liki Bornsztajn was born on August 26, 1927 in Nancy, France and died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz. In the spring of 1940, her family fled Nancy; this was the just the beginning of a period of upheaval, uncertainty and anxiety about the future.

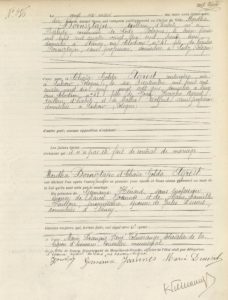

Liki was born on August 26, 1927 in Nancy. She was the daughter of Mordka Bornsztajn (or Bornstajn), a tailor who was born in Baluty, Poland (Baluty later became a Jewish district in Lodz) on February 13, 1897, and Golda Agrest, née Chaïa, a seamstress, who was born in Lukow, a town in eastern Poland. They were married in Nancy on March 26, 1927.

Liki’s parents’ marriage certificate; Municipal Archives of Nancy, Civil Status Marriage Registers 1927, January 3 – May 6,3 E 336

Liki was from a poor family. There is a note on the marriage certificate: “the wife having declared that she does not know how to sign [her name]”.

When Liki was born, the family as living at 38 rue Clodion in Nancy. Liki had an older brother, Henik-Albert Bornstajn, born on March 19, 1925 (we will come back to him later), and a little sister, Ida, who was born on July 24, 1926, but sadly died on July 14, 1927, just a month before Liki was born.

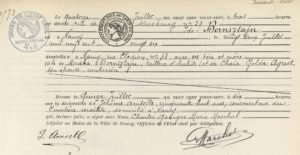

Ida Bornsztajn’s death certificate; Municipal Archives of Nancy Civil Status death register, 4 E 372

Two years later, the family grew larger when Marthe-Odile arrived. She was born on May 4, 1929 in Belfort. Mordka, her father, died before she was born, at the age of 32, on February 19, 1929, in Belfort.

Ten-year register of births including the name of Marthe-Odile Bornsztajn; Territoire de Belfort departmental archives 1 E TD 2

The last child, Wolf, was born on October 21, 1933 in Nancy. After her husband died, Golda, their mother, lived with her new partner, Gabriel Weiss. Wolf took his mother’s surname because his biological father was still married at the time.

Liki was born into a large Polish family that migrated to France in the 1920s. We can surmise that her parents moved to Nancy to find work. After the First World War, due to the high numbers of casualties, France welcomed large numbers of Polish workers. On September 3, 1919, the French government signed an immigration agreement with its Polish counterpart, which provided for the recruitment of Polish citizens, with equivalent employment contracts and the same pay as the French workforce.

Liki (on the left); Shoah Memorial in Paris, Serge Klarsfeld collection

We have no records about Liki’s education or her personal interests. A photograph from Serge Klarsfeld’s collection shows her as a teenager, with a friend. One can imagine that she enjoyed going out with her friends.

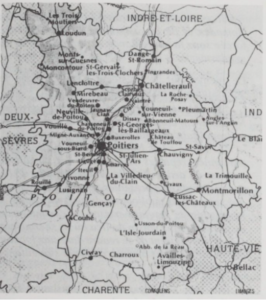

After the phony war, during the German offensive in May 1940, Liki, together with her mother, sisters and brothers took refuge in Saint-Jean-de-Blaignac, in the Gironde department in the southwest of France. It was a small village with a population of a few hundred, on the Dordogne River south of Libourne. Golda may have worked as a seamstress. After that, they moved to Bordeaux. A lot of other families from Nancy and the surrounding area moved to the Gironde department. In late 1940, the Germans expelled the Jewish refugees from Gironde and sent them to the Vienne department, because Gironde was on the coast and the Germans were afraid of being spied on. The Bornstajn family moved to Savigny-sous-Faye, a small, rural community to the south of Loudun.

The entire Atlantic coast was in the occupied zone (a restricted area as of 1941), including Bordeaux. The Vienne department, like 12 other departments, was cut in two by the demarcation line. Poitiers, Loudun and Châtellerault were in the occupied zone. The German anti-Semitic legislation came into force in the summer of 1940.

Map showing the various zones during the Occupation; Source: map based on Yvain Roué and Philippe Grange-Ponte, 2001-2012, “La France après l’armistice de 1940”; © cartography Réseau Canopé, 2016

Main towns in the Vienne department; Taken from the book “Un camp de concentration: Poitiers 1939-1945”

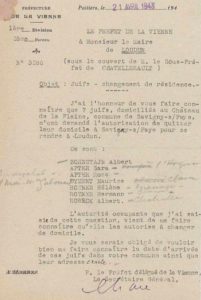

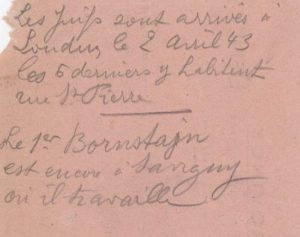

The eldest brother, Henik (Albert), lived in the outbuildings of the Château de la Plaine, as documented in this record from 1943. He worked a handyman on local farms. Along with six other Jews (three women and three men), he asked to change his residency. A later report from the prefecture shows that in the end, he stayed in Savigny-sous-Faye.

Request for the transfer of several Jews out of Loudun (1943); Vienne departmental archives

Handwritten note mentioning what happened to Henrik-Albert; Vienne departmental archives

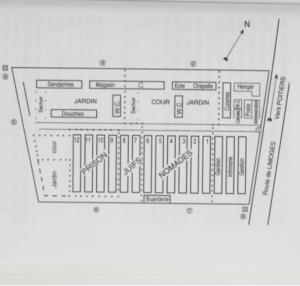

On October 9, 1942, Golda and her three children were rounded up and interned in the camp on the Limoges road in Poitiers.

As of October 1939, Spanish political refugees had been interned in this camp, then from the end of 1940 people who the Vichy regime called “Nomads” were kept there. In 1942, there were over 400 of them. The first Jewish internees arrived in the summer of 1941.

The camp on the Limoges road; Taken from the book “Un camp de concentration: Poitiers 1939-1945”

Conditions in the camp were extremely unhealthy, due to inadequate sanitary facilities and very limited food rations. The families were crammed into three Adrian barracks (wooden prefabricated huts) and had to sleep on the ground, on straw. There were no separate dormitories for the children, and no schoolhouse.

Golda was transferred to Drancy camp on October 15, 1942. She was among a group of 231 people, including 94 women, 86 men and 51 children. More than half of the group were Polish. Her three children remained in the camp in Poitiers because they were French citizens, which Golda was not. One can only imagine how distressing it must be for her to have to leave them behind and be sent to an unknown destination. Her children must have been equally sad, left to fend for themselves in the camp. Golda was deported to Auschwitz on convoy no. 42 on November 6 of the same year.

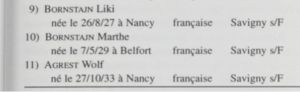

Rabbi Elie Bloch, with the help of Father Fleury, the Catholic chaplain for the “Nomads”, who worked in secret, managed to get some children out of the camp. He argued with officials about their status as French citizens. Jean-Marie Lemoine, the police superintendent for the Poitiers region, agreed to the release of 11 children on the grounds that they “qualified as French” citizens in November 1942. Liki, her younger sister Marthe and her half-brother Volf were therefore released on November 12, 1942. They were placed with Jewish or non-Jewish families (although in theory this was not allowed) in or near Poitiers.

Extract from the list of children liberated on November 12, 1942; Taken from the book “Un camp de concentration: Poitiers 1939-1945”

They were arrested again on July 23, 1943 and again interned in the camp on the Limoges road in Poitiers. Then, together with ten other children and escorted by several police officers, they were transferred to Paris on August 19, 1943. They travelled by train, in a cattle car. They were the last children to leave the Poitiers camp.

The three children were then placed in the care of the UGIF (Union générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews) in a children’s home on rue Lamarck, where all Jewish children were taken before being sent to other homes. They were then separated: Liki was placed in the home on rue Vauquelin, which took in young girls over the age of 15, while Volf was sent to the orphanage in La Varenne-Saint Hilaire. What happened to Marthe is unclear. Might she have gone with Liki? Given that Marthe was not rounded up with her sister, it would seem that she must have been taken in by someone else.

In July 1944, Aloïs Brünner, deputy chief of the German police in Paris, decided to deport all the children who were being cared for by the UGIF. He organized roundups in all the UGIF homes in and around Paris. He had the 33 girls from the rue Vauquelin home arrested, including Liki, during the night of July 21-22, 1944. They were then transferred to Drancy, where Liki was reunited with Volf.

They were deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, on Convoy No. 77. Both of them were murdered as soon as they arrived.

The anti-Semitic policies of the Germans and the Vichy government destroyed a large part of the family.

Martha survived, as did Henik Albert.

Identity photo of Henik (taken post-war); Ministry of Defense Historical Service, dossier ref. GR 16 P 74640

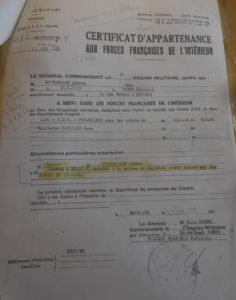

Henrik had joined the Resistance, in which he used the pseudonym Albert Boréal. He was formally authorized to use this name in 1987. He was awarded the status of Déporté et Interné de la Résistance, or Deported and Interned Resistance Fighter (DIR), and member of the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur, or French Interior Forces (FFI) (see annexes 4 and 5).

During his time at the Château de la Plaine, he met Rosa Apter, who later became his wife. In 1998, she filled out the testimonial forms that can be found on the Yad-Vashem website. Albert died on December 4, 2004 in Lyon and Rosa on October 13, 2012 in Avignon. Marthe died in 1984 in Créteil. She had two children: a daughter, Hélène, and a son, Ariel.

Sources

Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Caen :

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division, dossier ref. 21 P 482609

Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Vincennes :

- Resistance department, dossier ref. GR 16 P 74640

Shoah Memorial in Paris :

- Drancy files, search log and transfer log

- Serge Klarsfeld collection

Territoire de Belfort departmental archives :

- Ten-year register of births, 1 E TD 2

Nancy municipal archives :

- Nancy death register, 4 E 372

- Nancy marriage register, 1927,3 E 336

Communication via social networks with Martine Boréal, one of the two daughters of Albert Boréal, Liki’s older brother.

Bibliography

- Paul Lévy, Un camp de concentration : Poitiers 1939-1945, Paris, Sedes,1999.

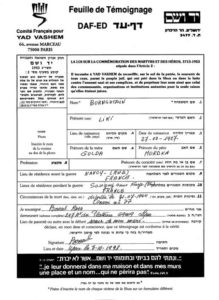

Annexe 1: Testimonial form in the name of Liki Bornsztajn, completed and submitted by Rosa Boréal

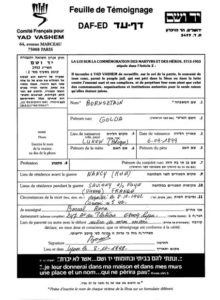

Annexe 2: Testimonial form in the name of Golda Agrest, completed and submitted by Rosa Boréal

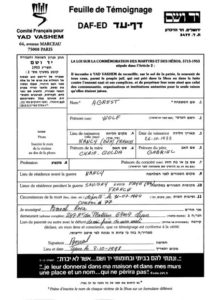

Annexe 3: Testimonial form in the name of Volf (Wolf) Agrest, completed and submitted by Rosa Boréal

Henik Bornsztajn’s French forces of the Interior membership certificate; SHDV, dossier GR 16 P 74640

Henik Boréal’s Deported and Interned Resistance Fighter certificate

Français

Français Polski

Polski