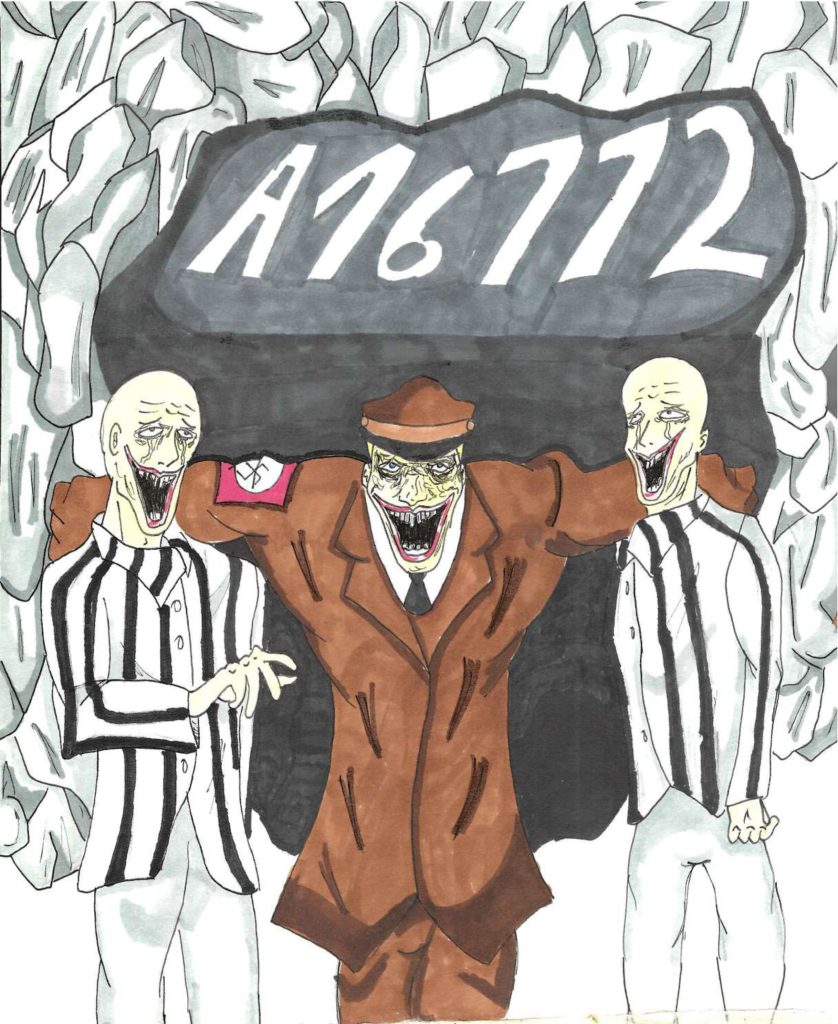

Marguerite MARCUS

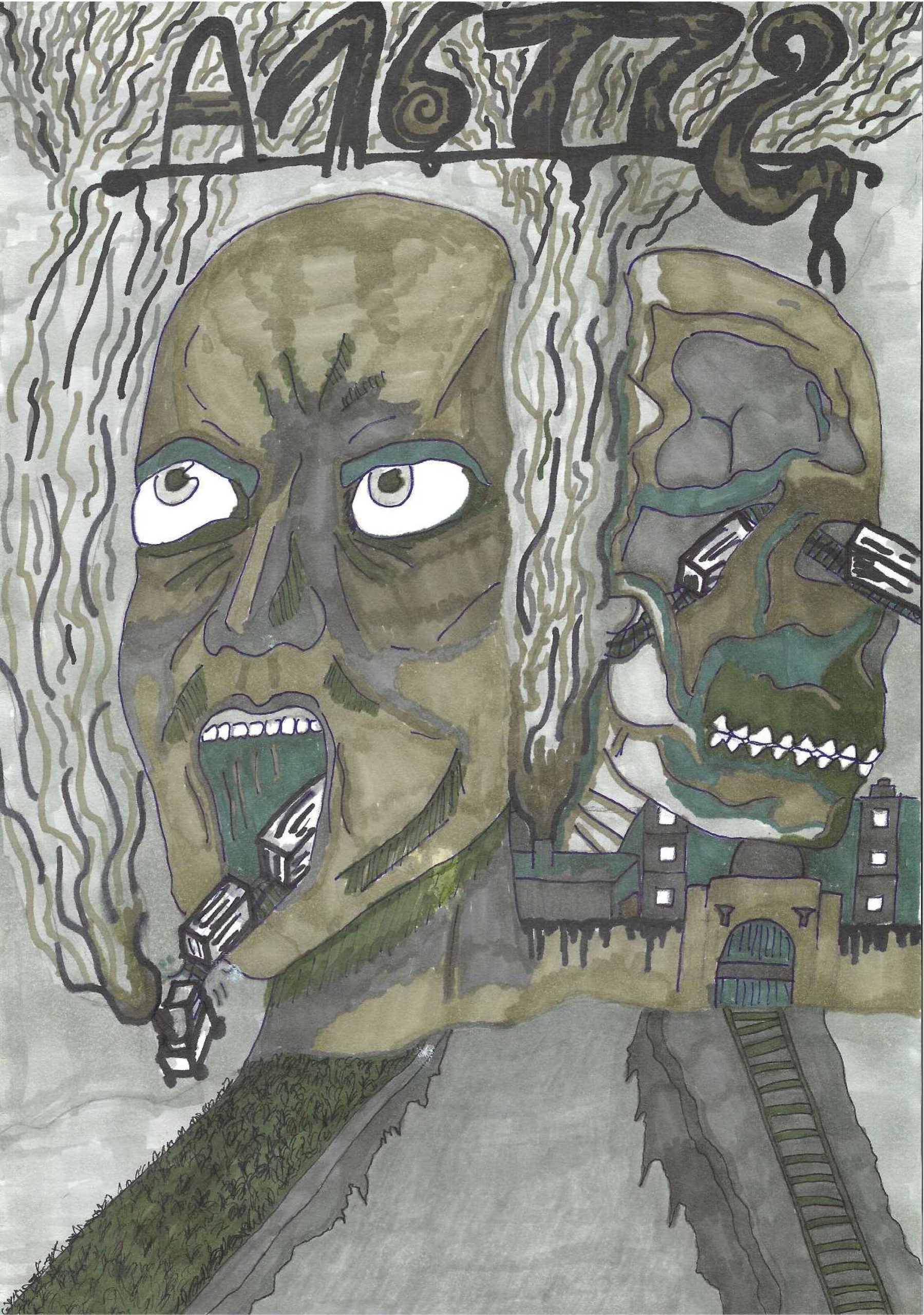

A 16772

An illustrated biography produced by the 12th grade students of class G3 at the Pierre Mendès France high school in Savigny le Temple, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, as part of the Convoy 77 project: Text: Oumou Bah, Amelle Bendounan, Merouane Biga, Soufiane Bouchneb, Rida Bouhaddachi, Antony Cardinali, Zara Chalaye, Lucas Dubarle, Bilal Embouazza, Cécilia Estorgues, Tina Galou, Valène Guillouard, Diéla Koubemba, Alicia Legros, Emie-Marthe Malonga, Sriram Muralitharan, Mahawa N’Diaye, Clara Nanteau, Tiya Phongthisouk, Abdullah Polat, Girgina Radeva, Vénus Senga Sahumba, Imane Tassafout, Sarah Tassafout and Clément Yanez

Illustrations: Bastien Angoston, Lou-Anne Balrick, Antoine de Aveiro, Maïna Cezar, Naomi Faridiala, Yasmine Le Floch, Emmanuel Nazebi, Tom Perret, Jade Pouilly and Valentin Sehairi

Introduction to the project

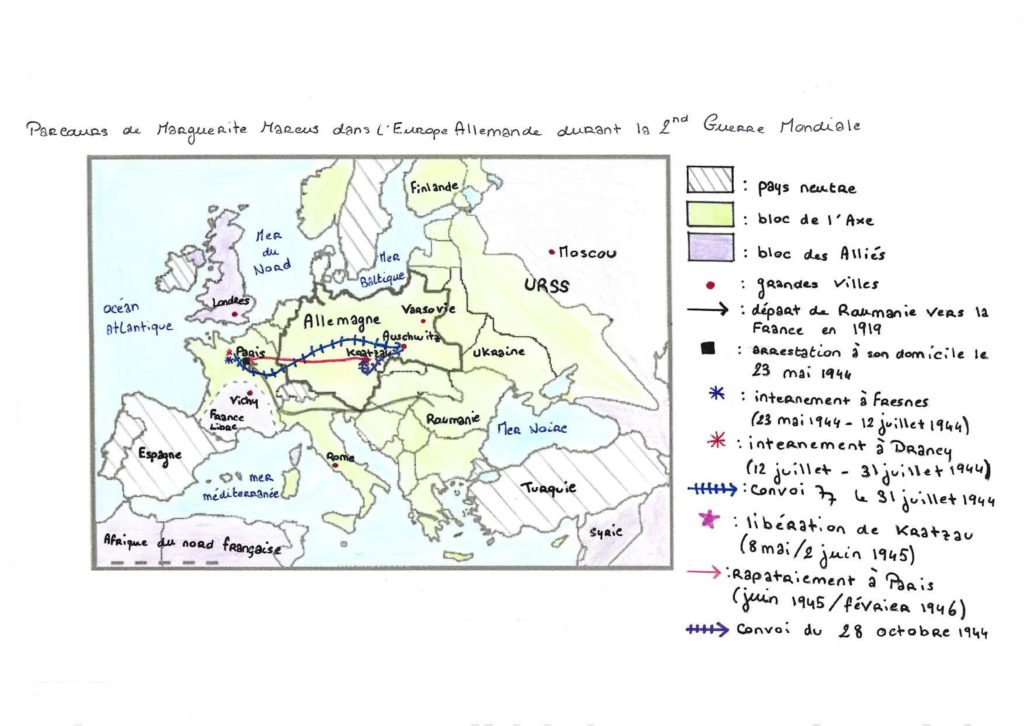

At the suggestion of our teacher, our class decided to take part in the Convoy 77 project for the French National Resistance and Deportation Contest. “Convoi 77” is a nonprofit organization which aims to compile the biographies of all of the people who were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 on Convoy No. 77. To this end, the association assigns a deported person to schools, in France or elsewhere, that want to participate in the project. We were assigned Marguerite Marcus, one of the 157 women on the convoy who survived.

Marguerite arrived in Auschwitz during the night of August 2 to 3, 1944, and stayed there until October 28, 1944. She was then transferred to the Kratzau camp, from which she was liberated on May 9, 1945. Since there are no testimonies available on the Internet to help us retrace her journey (how surprised we were to find that Marguerite was not known to anyone, even though she survived the Holocaust!), we decided to work together and undertake extensive research into her life. Our mission was to reconstruct the horrific ordeals that our deportee went through during the Second World War, by producing a twenty-page illustrated book. This biography includes the main events in her life: her childhood in Romania, her arrival in France, her arrest, deportation, arrival in the camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Kratzau, and lastly, her liberation and return to France.

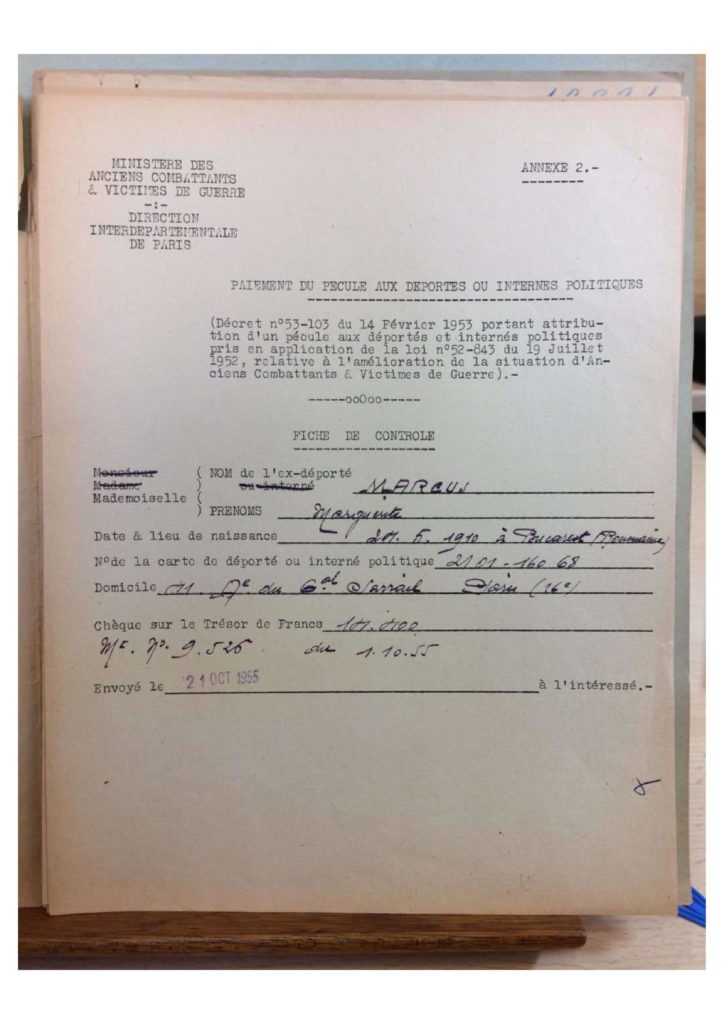

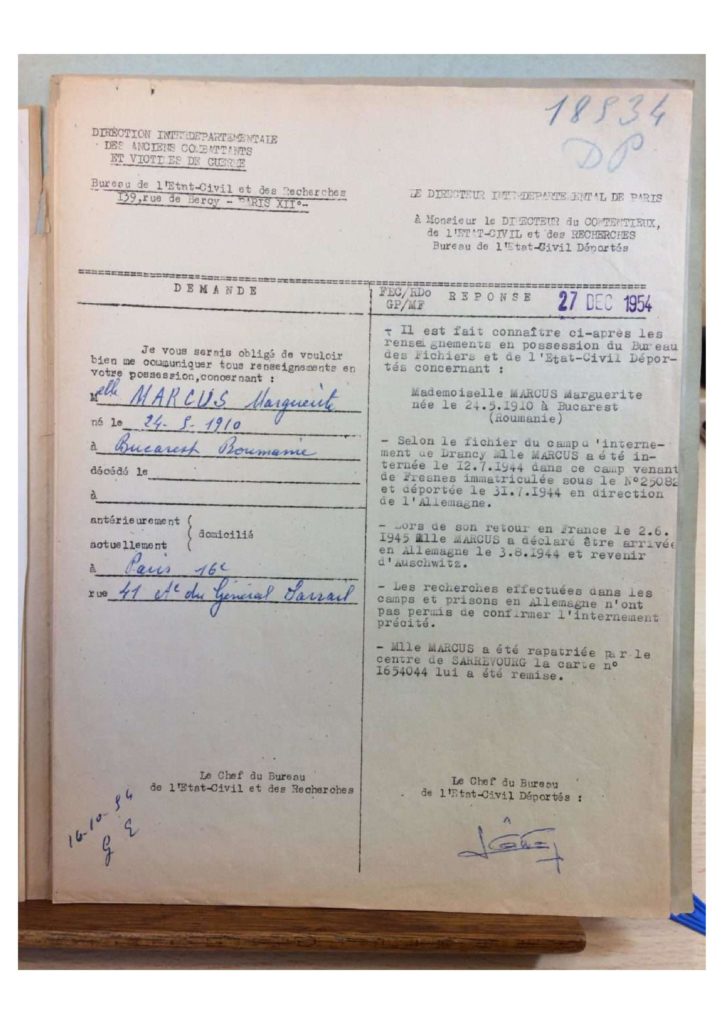

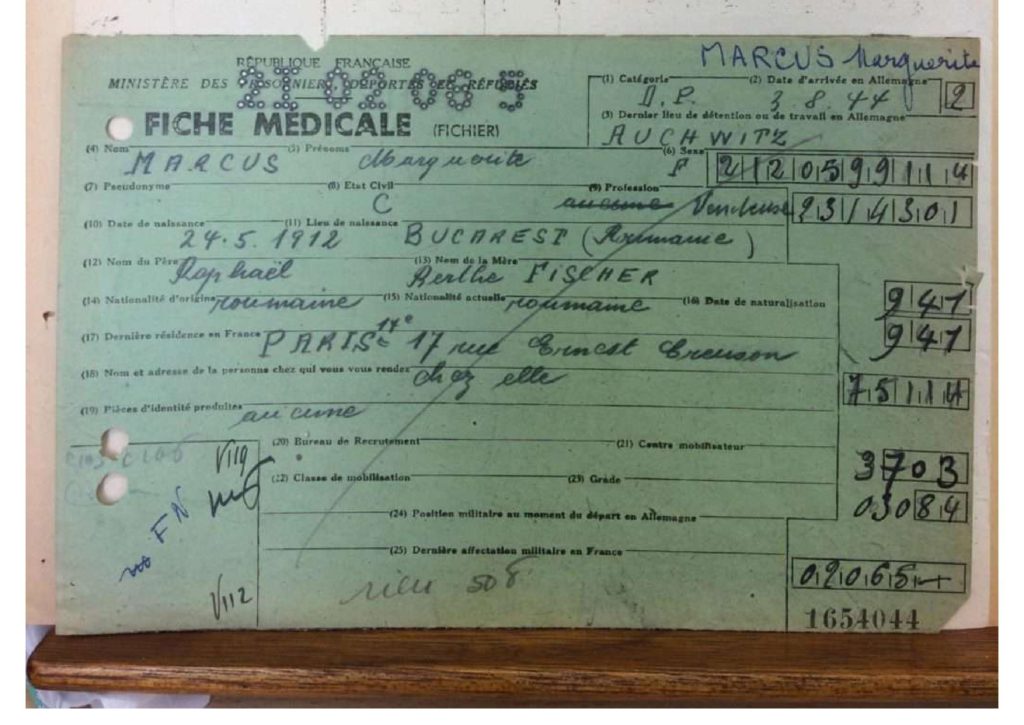

We began by splitting into several groups to try to piece together the clues about our deportee’s life, with the help of archives collected by the Convoy 77 association (some examples of which you will find in the photos). This enabled us to find out her date and place of birth and information about her background, her occupation, her family members and when and how she was deported. However, when we pooled the information gathered by each group, we found that there were discrepancies in the records, even, for example, as regards her date of birth! At that point, we realized that we would have to delve deeper.

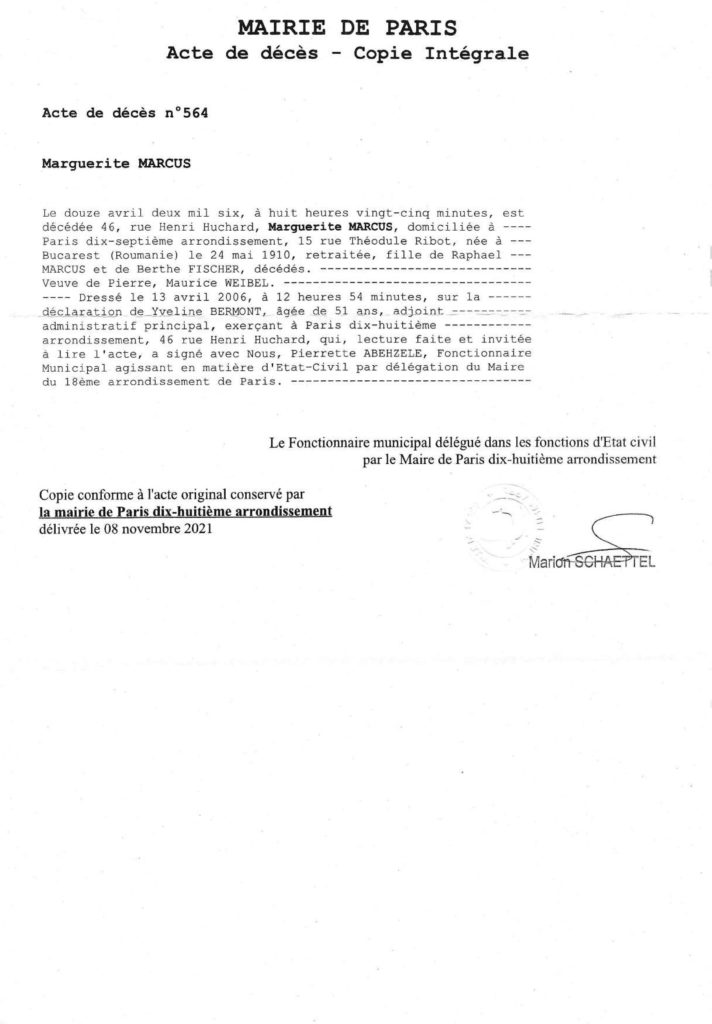

The first step was to look at the historical facts, via Internet research, in particular on the Shoah Memorial website and the French government memorial website, Mémoire des hommes. We also read books covering the period: the history of immigration in France, the way Jewish immigrants were treated, the political situation in France during the Second World War, the living conditions in the internment camps in France and Germany, etc. In addition, we scrutinized the testimony of another deportee, Régine Jacubert (born Rywka Skorka) who was on the same convoy as Marguerite Marcus. We thus linked the two together and figured that our deportee had experienced similar emotions, as well as the same unbearable living conditions as Régine. All this allowed us to produce a broad outline of a biography, but there were still many outstanding questions: we were unable to find out what had happened to her parents, for example, other than that her father was still alive in 1955. On the other hand, by inquiring at the civil registry office in Paris, we managed to obtain Marguerite’s death certificate, and thus discovered that she had been married! In addition, we have unraveled the mystery of Jean Landy, who is mentioned in the Convoy 77 archives as the tenant of the apartment where Marguerite was arrested in 1944, but with no further explanation. He turned out to be a Resistance member with the National Front, who was deported to Buchenwald! Finally, we wanted to use Marguerite’s Auschwitz deportee number as the title of our work, but the archives were full of numbers of unknown origin. Fortunately, we contacted a historian who specializes in the period and who came to our rescue.

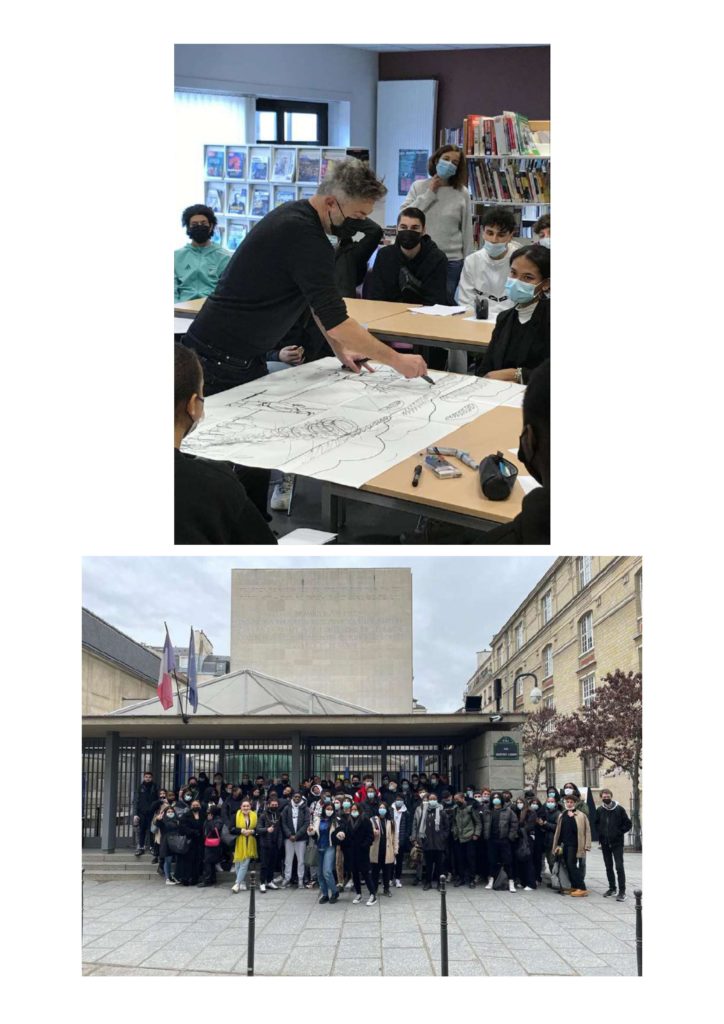

In January, Barroux, a professional painter, author and illustrator, came to visit our school. We prepared for this visit in advance, the objective being to seek advice about how to create an illustrated book that would be in keeping with the theme of our project. This enlightening encounter helped us a lot regarding the type of artwork to use, the drawing style, the choice of color or black and white, the way in which we could structure the text, and the appropriate tone for our work.

We then set about drafting our illustrations. In groups, we looked at the different phases of Marguerite Marcus’ life. Each group was made up of people with good drawing skills (our class actually includes a number of people majoring in art) who were in charge of the illustrations, while others were responsible for the written work and for figuring out which elements of Marguerite’s life we should reconstruct. We took our inspiration from photographs and books in order to make our work as realistic as possible, in the knowledge that we would sometimes be obliged to be “inventive”.

At the outset, the first difficulty we encountered was the different artistic styles of the people in charge of the drawings, a problem we solved by deciding to mix the various styles, thus creating an original and truly collective piece of work. Since we had no photos of our deportee, we did not know her face, or indeed the faces of the other people in her life… As for her feelings, they were very difficult to imagine: how could we put into words situations that we had not experienced ourselves?

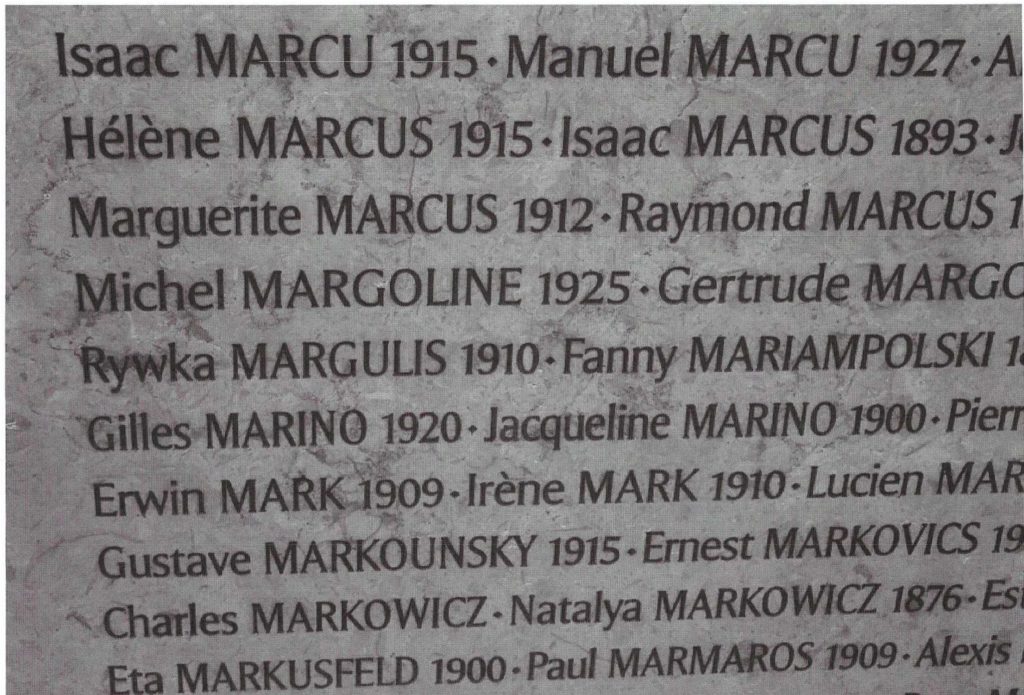

In February, we visited the Shoah Memorial in Paris with the aim not only of gathering more information and photographs, but also to visit the museum. We watched the testimony of three people who were victims of the Vel’ d’Hiv’ round-up. We saw the Wall of Names, and of course, seeing Marguerite’s name on it was a very emotional experience for us. It was impossible not to feel deep empathy for the millions of victims. Seeing the deportees’ clothing in particular was an inexplicable feeling that made the atrocities inflicted by humans all the more tangible.…

This project enabled us not only to enhance our cultural knowledge of history but also to learn about the atrocious and inhumane circumstances in which the Jews were deported. Unfortunately, we were not able to meet Marguerite, who has passed away, nor any other victims of this nightmare, except for a few lucky students who specialize in HGGSP (History, Geography, Geopolitics and Political science), who had the privilege of listening to the testimony of Ginette Kolinka, who was invited to speak at our school.

We thoroughly enjoyed this project, launching ourselves into the unknown, starting from almost nothing, not knowing what the project would be like and whether we would succeed or fail. It enabled us to work collectively, to learn to communicate with each other and to accept each other’s strengths and weaknesses, so that the texts would all fit together, giving the impression of having been written by the same person, while remaining faithful to the period about which we were writing. Each student had a task, a responsibility and a role to play. We met in the library every Friday afternoon where, like detectives, each of us a Sherlock Holmes in the making, we worked to put together the pieces of Marguerite’s story. Completing a search and finding useful material for the whole class was like unearthing buried treasure.

Unfortunately, we also knew that we didn’t have enough time to create a book worthy of publication, and that we had to accept that we could only do so much, at our own level, and in the time available. But we are proud to say that we all contributed to a “fine” project, as a team. It’s something that will stay with us forever, a lasting reminder of our high school years. It has become a part of us.

This project also helped us to broaden our knowledge of the Second World War, by going beyond the history curriculum. For example, we became interested in the human aspect of this tragedy, in order to understand that beyond the genocide, above all, were real people. In addition, even though this is a distressing subject, we are aware that we have paid tribute first and foremost to our deportee, to whom we have become quite attached, as well as to all the other victims, and that we have fulfilled our duty of remembrance.

It is essential that we never forget the Second World War and all the victims, and that we learn from the past, so that such a tragedy can never happen again. As the years go by, there are fewer Holocaust survivors alive, and soon they will all be gone. Young people must pass on this knowledge to future generations: we are the witnesses of the witnesses! We do not want all those who suffered to be erased from our collective memory, but rather to remember that they were all people of incredible courage who have earned their place in history.

1 – A CHILDHOOD UNLIKE ANY OTHER

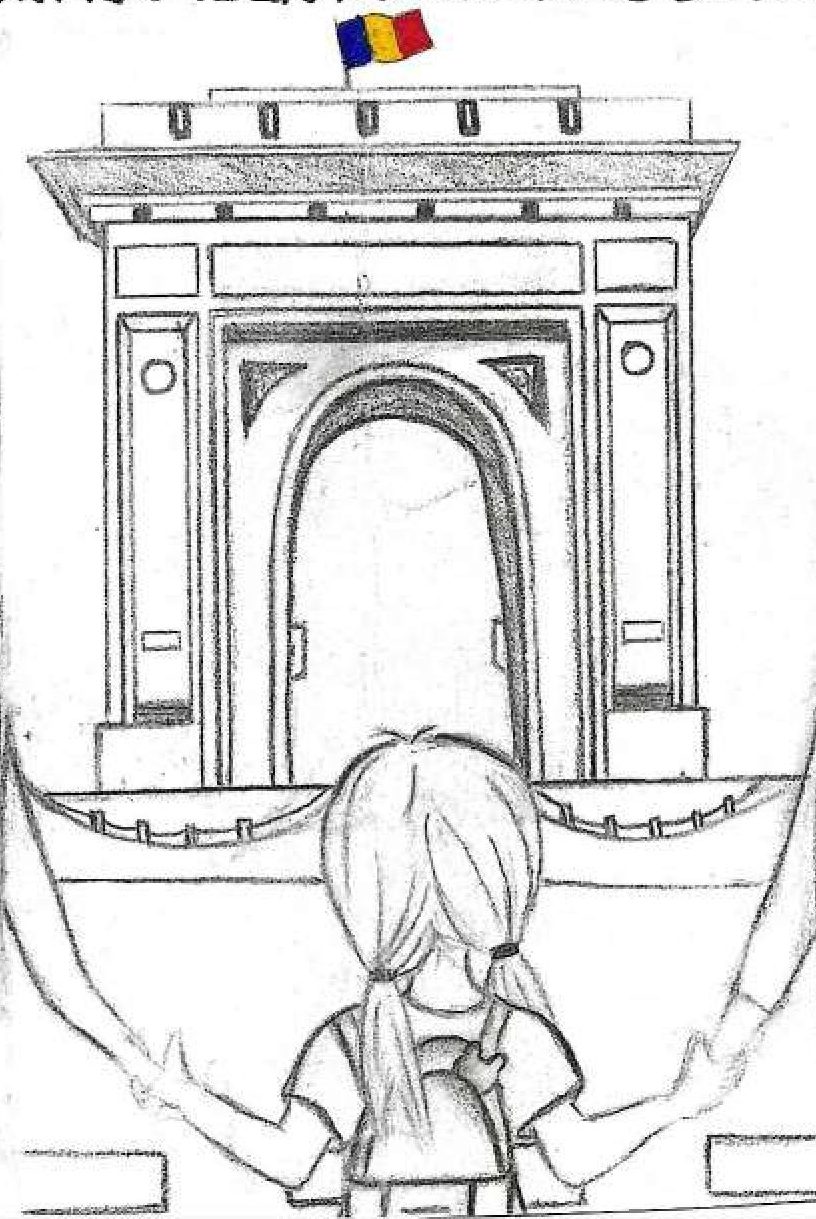

My name is Marguerite Marcus and I would like to tell you my story. I was born on May 24, 1910, in Bucharest, Romania, where I lived with my father, Rafael Marcus, and my mother, Berthe Fischer. Being Jewish, and poor, we were first threatened by the pogroms that ravaged our community, and, after the First World War, by the Hungarian-Romanian war and the depression.

I was still a child when my parents decided that our lives must change. The ideal country? France, which in our eyes stood for human rights. A country that needed manpower after the bloodshed of the First World War, and where peace prevailed. At least, that’s what we believed.

And that was why, in 1919, we moved.

We had to abandon everything, to leave it all behind, and never look back. Starting over in another country… It wasn’t going to be easy. I wasn’t sure if I had it in me.

When we arrived in France, we settled in Paris. My parents enrolled me in a girls’ school in the 17th district. I had a tough time in school and didn’t have many friends. The French children didn’t want to mix. I didn’t understand why they shunned me just because of where I came from and my religion. I began to question my identity. Must I deny who I was, for the sake of others? I began to write a journal.

2 – THE WAR

1930: I work as a salesgirl in a small grocery store that my parents opened when we arrived in France. I grew up here, behind the counter, serving all kinds of customers. We live a frugal, simple life.

1933 : Times are tough for everyone. France is struggling with the depression that has spread from the United States. We are worried. On the radio, we hear about the emergence of an anti-Semitic regime in Germany. It seems that the Germans want revenge. Atrocities were perpetrated against the Jews during Kristallnacht in 1938. That says a lot about what is in store for us if the Germans ever come to France.

September 3, 1939: France has just declared war on Germany.

May 10, 1940: I have just heard on the radio that after eight months of war without any real fighting, the Germans are attacking France.

June 14, 1940: Paris is now under German rule. There are photos in the newspaper of Hitler marching through Paris. I’m horrified.

3 – THE NIGHTMARE BEGINS

1940: France has been defeated and Germany has invaded. I’m scared. They say that the Germans are all anti-Semitic. What is to become of us? France has been divided in two. I live in the occupied zone where the Germans have taken over, assisted by the Vichy regime that is in charge of the free zone in the south. We, the Jews, are already being targeted. New laws have been introduced. A law passed on September 27 has made us a separate category of people. We have all had to register ourselves as Jews and display a sign on the front of our stores. They have to be listed as Jewish property. The thought of losing the store makes me anxious, my parents and I have invested so much money, time and hope into our business.

- It’s been a while since I’ve written anything or sketched cafés and landscapes in my journal. I’ve lost my joie de vivre. I’m 31 years old and I feel that life no longer has any meaning. I know subconsciously that nothing will ever be the same again. I’m reduced to being just a soul in a suffering body. These young years are bleak. I’m not living the life I had imagined, a life filled with first romances and parties. But sadly, I have no control over my destiny or that of millions of other Jews.

The only good thing that has happened to me is that I met dear Jean Landy and his sister. They are not Jewish, but they are revolted by what is happening to us. It seems that Jean is a Resistance fighter, and that he is involved in the National Front, a communist resistance movement!

4 – BECOMING A TARGET

Life is becoming increasingly difficult. So many stores are closed now. Circumstances were such that ours finally succumbed too. It’s gone, we’ve lost it. The French and German authorities have taken the Jews’ businesses away from them. More new laws have been enacted. We are being made to live like animals. We can no longer work or hold bank accounts. I’m far from the only person saying that that our meager income is not enough to live on.

July 16-17, 1942. Everywhere I turn, Jewish survivors are only talking about one thing. 12,884 people have been rounded up, including 4051 children. Almost the entire population has been locked up in the Velodrome d’Hiver. I don’t even want to imagine what’s going on in there. I’m so relieved to have avoided it by hiding at the Landy’s place. But I know full well that I’m not still safe.

November 1942: The whole of France is now occupied by the Germans. The free zone has just been invaded. We are becoming increasingly stigmatized, and since June 7th we have had to wear a yellow star when out in public.

I am apprehensive about this new life that I am forced to lead. I hardly dare to go out anymore. I am afraid of being stared at by everyone. And even more afraid of being arrested.

5 – AN ALMOST PERFECT HIDING PLACE

We keep hearing rumors of more and more Jews being deported on the convoys. Every day we hear that someone else has gone. I’m told that Elise, an old lady who often came to my store, has been deported. She used to buy lemons. It breaks my heart to imagine Elise in those trucks, in such appalling conditions; it’s totally inappropriate for someone of her age. Not only that, but she walks with a limp. I sincerely hope she’ll be OK. One thing is for sure, I will never forget her beaming smile and her sweet voice.

I am now permanently in hiding with the Landy family, on rue Desbordes Valmore in the 16th district. Like so many other people, I use an alias, Marais, to mask my identity and in the hope of avoiding deportation. I am aware of the danger this represents and the risk I’m taking, but I have no choice. My father is also in living in hiding.

23 May 1944: Tomorrow is my birthday. I am at Jean Landy’s house, waiting for his sister. Suddenly, we hear loud knocks at the door. I jump up, rush to the peephole and see them: German soldiers! I have no way out …

When I wake up, I feel the jolts of the road. I remember: they broke down the door, knocked over the lamp and then I passed out. And now here I am, in a Wehrmacht truck, I guess. I look around me and see other prisoners. One of them must be no more than four years old. Another is silent, with a vacant stare, while the child trying not to cry.

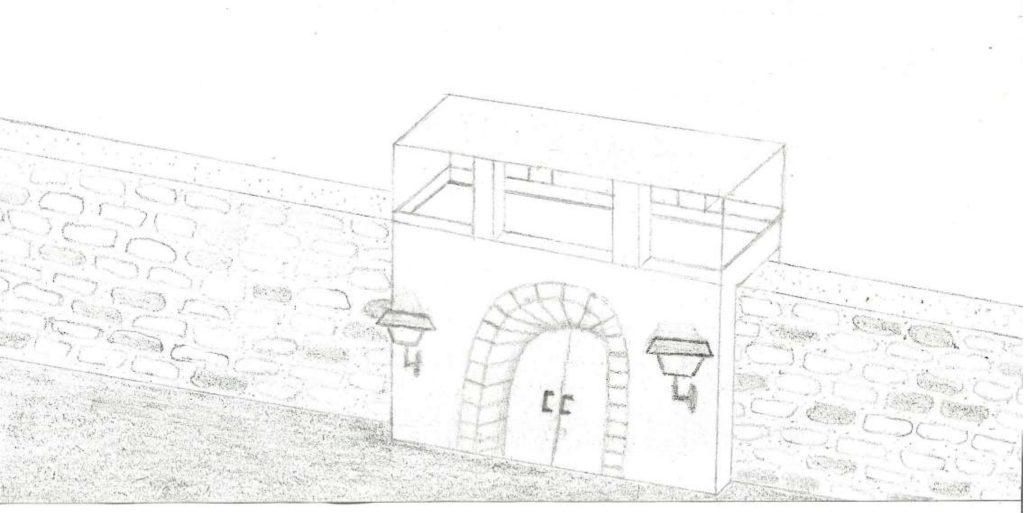

The soldiers take me into a prison. I thought I read on the sign on the gate that said “Fresnes”. I realize that I am in one of the worst prisons in France. I see damaged buildings and an unimaginable number of people. Prisoners. Little do I know that in a few days’ time, one of them will be shot down before my eyes.

No. I want to struggle, or curl up on the floor. But I keep moving. I have to move on. To survive.

some of the others, can’t get to sleep. The silent man from the truck is in the same cell, on the bed. All night long, he only says one thing, staring at me: “Are you Jewish? I don’t nod, nor do I deny it. This is the last time I hear him utter even a single word.

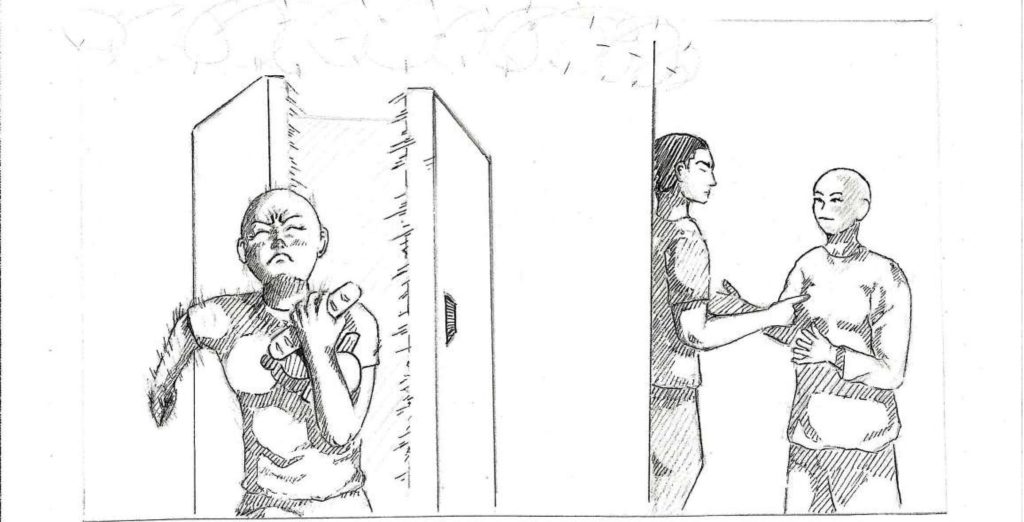

Just as I’ m finally dozing off, two guards armed with guns come to fetch me. There are three of us, and they put us in different rooms. I am trembling. I know what is going to happen next. One of the guards keeps an eye on the door as he paces up and down the hallway. The second stands in front of me. I can’t seem to open my mouth to answer his questions. My stomach is in knots. He asks me what I was doing at Jean Landy’s and if I knew anyone connected with the Resistance. He promises me a hot meal but I don’t answer. I never did see that hot meal.

As I was being led back to my cell, I ran into Blanche Auzello, the famous manager of the Ritz who was well known for her resistance activities. I had seen her go into one of those notorious rooms. Her face is swollen and her head is down. The guards have to drag her along because she can hardly walk.

I spend two months in this prison, in a state of torment, with no news from the outside world. Nevertheless, I hear that the Germans are moving large numbers of prisoners.

6 – A ONE-WAY JOURNEY

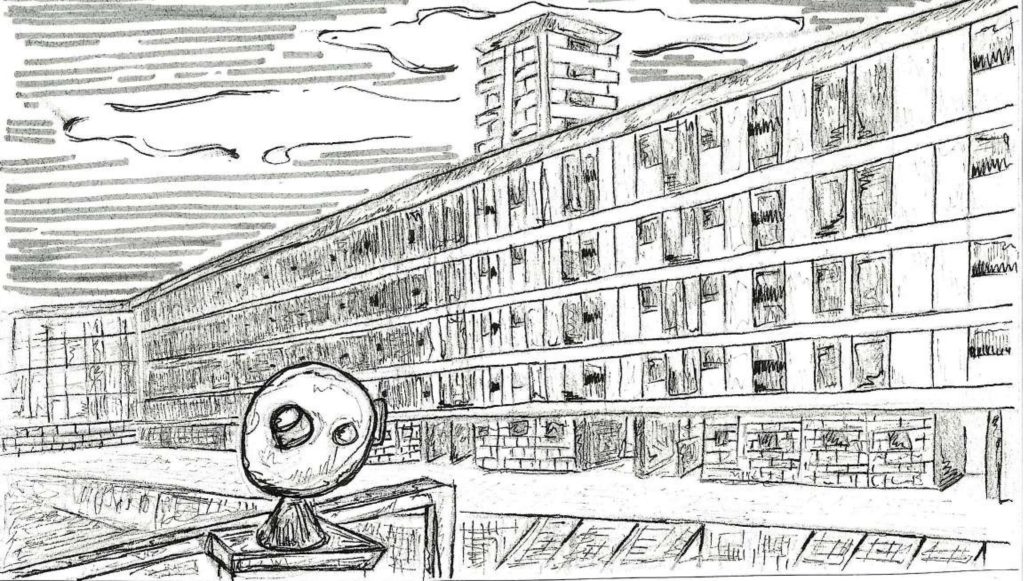

July 12, 1944 – The guards come to take me out of the vile cell in the Fresnes prison and put me in a truck with some other prisoners. We arrive at a huge internment camp in Drancy. It looks like an enormous prison. The camp is made up of five towers with a central building. At first glance, it seems that thousands of us are all gathered together in this place.

The camp seems quiet. I don’t know what to expect. We are immediately separated into two groups. The men on one side and the women and children on the other. I don’t feel at all at ease. On the contrary, in fact, I have a bad feeling about all this. I feel like I’m all alone in the world, as if I’ve landed in a place cut off from real life. I try to pull myself together, I don’t want to lose hope.

I decide to go to talk to a group of people to find out why they are here. They’re Jews, just like me.

For two weeks, we live in squalor. The soldiers put us in unfinished buildings. and we had to endure deplorable hygienic conditions. We had to endure appalling sanitary conditions. We are permanently stifled in the heat of the summer, we sleep on filthy straw mattresses, with a few washbasins as sole means of washing. We have very little to eat, and most of all, we are worried about what will happen to us. All we know is that we are going to be sent to labor camps in Germany, but we don’t know any details.

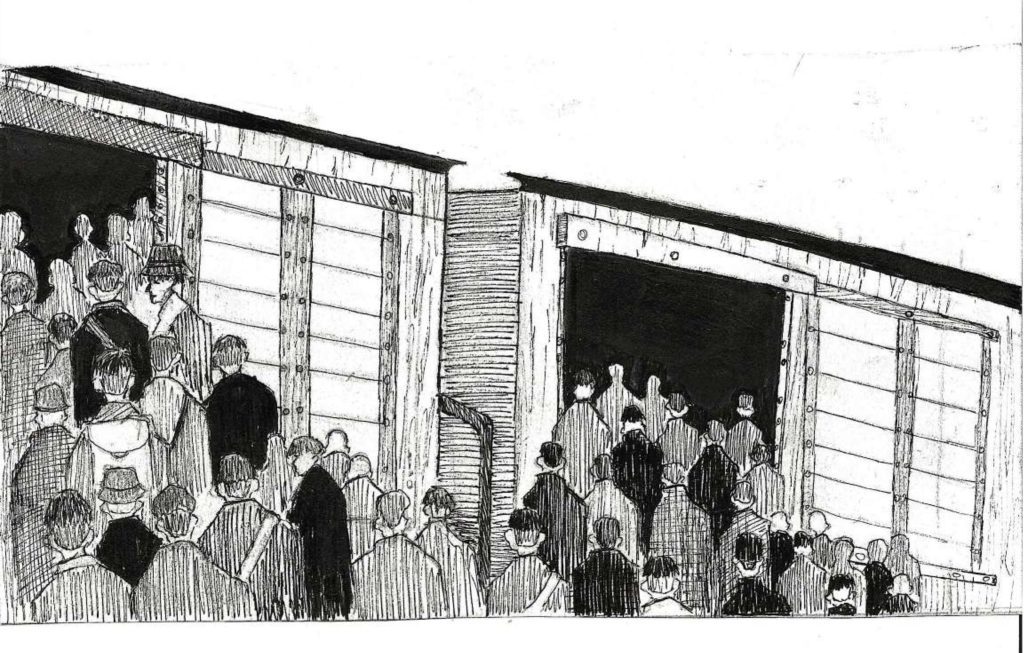

July 31, 1944 – A fortnight later, a fortnight of misery and fear of the unknown, we are moved again. This time, we’re put on a train made up of cattle cars. Our convoy, it seems, is number 77. The SS officers separate the men from the women, but everyone has to scramble up into the wagons, even the old people, sick people, pregnant women and women with children. So many children, it’s appalling. Why are they here? Are the Nazis even going to have the nerve to make the children work?

Someone whispers in my ear that the despicable man in charge of the transports from Drancy, Aloïs Brunner, was also responsible for rounding up the children. Yet I don’t see any anger in the deportees’ eyes. Everyone in the station has the same expression. All I see is resignation.

There are soldiers on either side of the doors. We board the train in single file. There are so many of us in the cars that we soon find ourselves squashed in one against the other. The children are crying and some of the women are praying.

7 – THE TORMENT BEGINS

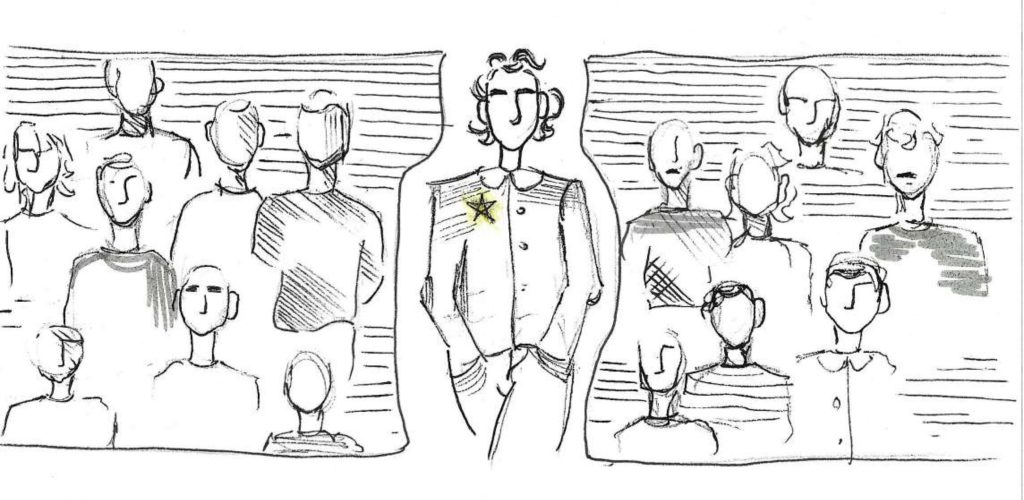

August 3, 1944 – At last, the train stops. The doors open into the darkness. Soldiers with dogs yell at us to get out: “Geh raus! Geh raus!”. They separate us into two lines, the men and women on one side, the older people, disabled people and children on the other. I hear soldiers asking young people if they are over 16. I realize that they are selecting those who are fit to work from those who are not. The first line leaves first. We leave afterwards and are sent in another direction…

We are taken into the camp. There’s a nauseating smell in the air and I wonder where it’s coming from. Next, we go into a room where we are ordered to undress as the soldiers look on with their cruel eyes. This is the first time in my life that I have ever been faced with such a humiliating, degrading, embarrassing situation. One by one we are shaved all over, including our hair and even our private parts. Then a number is tattooed on our forearm. This number becomes our identity and we have to recite it in German every time we are asked.

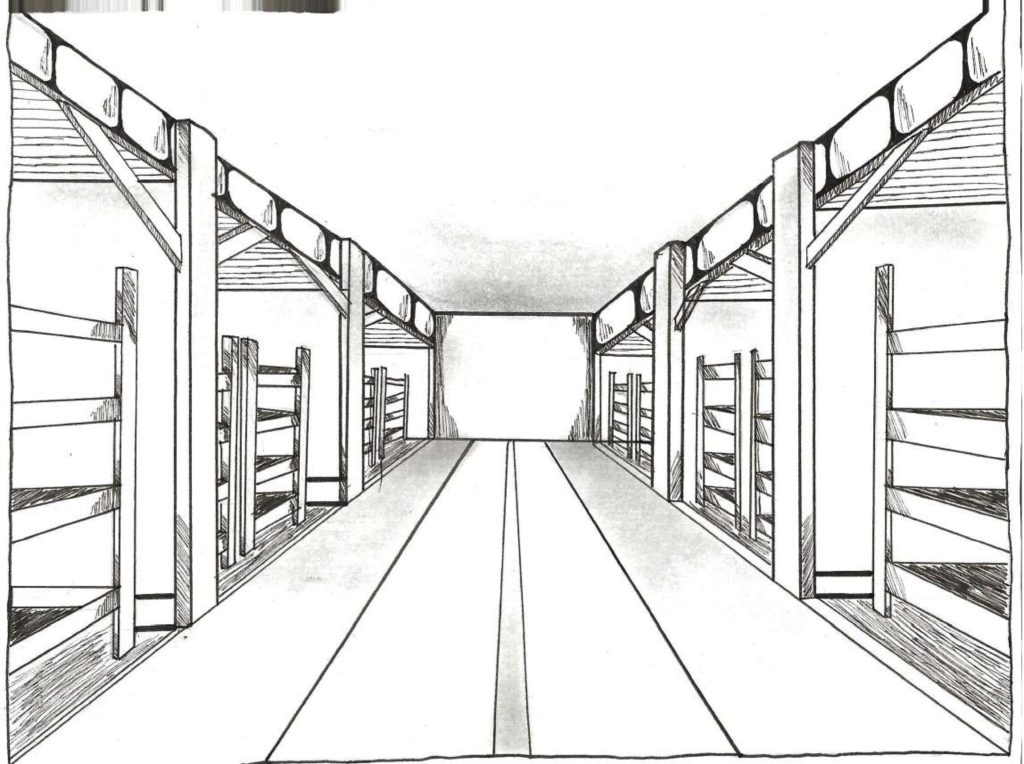

Finally, we are taken to the dormitories. To say that we all want to sleep is an understatement. But how can we get to sleep when we are surrounded by SS guards patrolling the camp, which is enclosed by electrified barbed wire?

The kapos, who tend to be the most violent prisoners, guard and supervise the other inmates. They wear a green triangle to make them stand out. The camp regulations allow the SS officers to punish the prisoners and they do this in the most ruthless way imaginable. During roll call, some prisoners collapse due to the adverse weather conditions and they are even punished for this.

8 – HELL ON EARTH

Everyday life for us as women is about being segregated from the men. We are not allowed to have any contact with them at all. It’s hell, this quarantine. We have roll calls twice a day. The rest of the time, we have to sit on the ground until a whistle blows, which is the signal for us to jump up and rush off to fetch stones. The sole purpose of this task is to wear us out and dehumanize us, because all this carrying stones back and forth is futile.

Once a day, we are given a tiny portion of soup and bread. The general atmosphere is terrible: we are surrounded by screaming, we are scared, and the cold is atrocious. Yet despite all this, I want to survive!

There are regular selections, during which we have to appear before the SS officers, who tell us to go to the left or to the right. Every day, I am overwhelmed with anxiety at this crucial moment, because I know that if I am sent to the left, I will be subjected to the horror of the gas chambers. If I am sent to the right, I will survive, albeit in horrible circumstances. Sometimes I catch myself thinking that being sent to the left might be the better alternative, to put an end to this miserable life…

9 – SURVIVING

The toilets, one beside the other in a line, offer no privacy whatsoever. I hold it in almost all day so I don’t have to go to this unhealthy, squalid place too often. Fortunately, like many other women, I no longer have my period. I’m sure that these bodily dysfunctions are due to the trauma. My every move, my every action, is a burden.

We are no longer human in the eyes of the Nazis! A woman in our barracks had her twins taken away from her when she arrived in the camp and has just heard that they have died as a result of Dr. Mengele’s cruel medical experiments. This monster tried to sew them together to make Siamese twins. I have no words. How is it possible for a human being to do that?

By order of the SS, a women’s orchestra has been set up in the camp. The idea is that they will play music as we work. The SS ask them to play during official visits or to entertain the guards and officers. We are literally exploited like slaves to brighten up their days. Seeing us exhausted doesn’t worry them at all. They probably enjoy it immensely, in fact.

I try, nevertheless, to be strong in front of the younger ones. They confide in me because they see me as a mother figure. Being supportive of others is one of the reasons that I’m still alive.

10 – A GLIMMER OF HOPE

October 1944: What day is it today? I’ve lost all sense of time. Suddenly, some wakes me up unexpectedly. The Germans throw me and several other women into a train without telling us where we are being taken. We are all crammed into a cattle car and I can hardly breathe. The journey seems interminable. Women are dying in front of my very eyes. The atmosphere is dismal, fateful even. I too am afraid that this will be my last day on earth. Everyone is tense and edgy.

After several days on the train, we finally arrive and are violently dragged off the train. I realize that we are in Germany, or at least in German occupied territory. I discover that this is the Kratzau camp, in Czechoslovakia. We are taken to filthy, small and dark dormitories. We are very cramped. The soldiers soon make it clear that we are here to work for the Nazis.

Every day is the same:

– Morning: roll call and breakfast

– Daytime: interminable work in the factory

– Evening: boiled potatoes with bread.

The portions we are given are ridiculous. Our only way to get by is to “organize” something. For example, some of us divert the guards’ attention while others steal food.

Alternatively, we make friends with supervisors so they treat us better and do us favors. We have to do this to survive. Those who don’t do it have a really hard time.

Despite this, I prefer Kratzau to Auschwitz because our lives are less stressful without the pressure of the selection, the risk of being sent to the gas chambers and without the smell from the crematoria.

Days, weeks and months go by, but we hear talk of liberation being imminent. Planes fly overhead. The Germans are worried. You might think that this would make us feel better, but actually it makes the waiting seem longer and more tedious. I try my best to keep my hopes up.

11 – FROM DARKNESS INTO THE LIGHT

May 9, 1945: No one dares move. My heart is pounding. I sense freedom on the horizon but I don’t know how to react. I am torn between the joy of knowing the end is near and the panic of not knowing what will happen next. Will our camp be bombed after all? Will the Germans decide to kill us all before the Russians arrive? Will someone come to rescue us? Or will they let us die?

Later on, we all go out into the yard. The Germans have all disappeared. All of a sudden, we see a group of soldiers approaching. One of them comes in to meet us, climbs up onto a table and shouts: “Ladies, you’re free!”.

I can’t believe it. The words keep going round and round in my head. Free. I am “free”. I have no words. I can’t describe what I feel. I can’t believe it. I’m speechless. All around me, women drop to the ground in shock. I feel numb, almost paralyzed.

12 – RETURN TO LIFE IN FRANCE

I was among those who were cared for by the Russians. We were hungry and cold. After many long hours walking, I was able to take a train to Sarrebourg. The return to France was slow. I had lost a lot of weight, I was weak and exhausted, but my courage (yes, I dare to say it: it was courage!) got me back safely. I was examined by doctors who noted that my health was very poor, but let me go home. I had managed to avoid typhoid fever and all the other horrors.

Thanks be to God, my father is still alive! I go to find him. I can’t help but break down in tears of relief. Our life has been totally destroyed, but we must carry on, just the two of us, since my mother is gone. I have a duty to carry on, for the sake of all those who didn’t have the chance to come home alive. Will I make it?

Using every conceivable means, I managed to track him down. He too was arrested and deported, to the Buchenwald camp. Unsurprisingly, his experience was just as tragic and degrading as mine, but he too made it out alive.

1955: Time has passed. I am still trying to rebuild my life. The after-effects are still there, but I am trying to move on and not let the trauma hold me back.

I have been recognized as having been a “political deportee”. This is the only evidence I have of what we all went through and I hope that it will be the first step in ensuring that our story is heard the world over.

I married Pierre, the son of the Weibels, another family that was decimated by the Holocaust, and we moved to 41 avenue Général Sarrail in the 16th district of Paris.

I am sharing my story with you because as a victim of this genocide, it is important that I tell the story of the slaughter, and no one can describe what we experienced better than we can. However, there are many more who are unable to do so. The deportees cannot always find the words. Perhaps they also feel that people do not really want to listen to them. We are all still shaken. But let us persevere, let us honor the millions of victims. So much remains to be explained and we cannot look the other way.

Some people feel guilty for having survived and returned home. Those who really experienced the genocide are no longer here to bear witness. And then there are those who lost their faith in Auschwitz, both their belief in God and their faith in humankind.

There are still so many things to discover and understand. But as Primo Levi would say: “For those who have been through hell, there is no reason why”.

Français

Français Polski

Polski