Daniel NAIMAN

Resistance to deportation in France and in Europe

2023-2024 round of the French National Resistance and Deportation Contest.

Prosopographical research: some biographical details about the lives of Camille Meyer and Daniel Naiman, who were deported on Convoy 77.

In his book Le Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Jews deported from France)[1], Serge Klarsfeld wrote of Convoy No 77: “The number of deportees was 1,300. Convoy 77 (…) carried more than 300 children under the age of 18 to the gas chambers in Auschwitz. (…) 291 men were selected with registration numbers B 3673 to B 3963, as were 283 women (A 16457 to A 16739). By 1945, there were 209 survivors, 141 of them women.

“I will give them an everlasting name” (Isaiah 56.5, Bible KJV)

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The Convoy 77 European project

- The UGIF

- The roundup on rue Vauquelin

- Daniel Naiman

- Annex

- Bibliography

Opening remarks

In researching the lives of Camille Meyer and Daniel Naiman, both of whom were deported on Convoy 77, we found a great deal of information about Mr. Naiman’s life. Details about Ms. Meyer’s life, on the other hand, are few and far between, but our research has enabled us to sketch a broad outline of her life nevertheless.

We requested some information on arolsen.org: the Arolsen Archives sent us some records about Mr. Naiman, but they have nothing on Ms. Camille Meyer née Belaich. On other research sites, we found only snippets of information about her.

As we attempt to keep the memory of Camille Meyer and Daniel Naiman alive, it is important to bear in mind that our work was carried out as part of the Convoy 77 European project. We must also remember the reason Ms. Meyer was staying in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, and the roundup that took place there.

Introduction

The two biographies we have written are both about French deportees. They were written as a contribution to the work of the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, a European project which aims to document the lives of all of the people who were deported on this particular convoy.

To survive is also to resist. There are many different types of resistance, and not everyone resists in the same way. Many deportees who survived were unable to talk about their experiences until years later, either because they found it too difficult to speak about such unspeakable events, or because they were trying to live some semblance of a normal life again. There was also a limited “audience” for their stories, as the truth about deportation and the camps was only gradually coming to light. For a long time, France continued to believe that the Vichy regime never existed in law. The prevailing view was that the Republic had been temporarily transferred to Algiers and London. This was reflected in the decrees that reinstated republican laws, which were passed as early as 1944[2]. The French President Jacques Chirac acknowledged the legal validity of the Vichy regime in 1995, thus paving the way for a new chapter of remembrance for Resistance fighters and deported persons. For example, the French Council of State, the supreme administrative body, was then able to take into account the State’s responsibility for deportation and spoliation, which led to compensation for victims and their heirs.

Continuing to research the lives of Resistance fighters is a way of refusing to let them fall into oblivion, and of keeping their memory alive. Few of the survivors are still alive, and future generations have a duty to keep the flame alive, to ensure that their shattered lives will never be forgotten.

Present and future generations have a duty to remember them, as there are so few written testimonies to pass on their legacy. In France, on April 24 each year, we pay homage to the victims of deportation. In doing so, we make sure they will never be forgotten.

There are stories about the day-to-day life of a doctor and his wife, who was a nurse, during their time in Auschwitz. Eddy de Wind’s book “Terminus Auschwitz” is one such example. This book is one of the few to have been written while the author was actually in the camps, so his memory did not fade over time. The book was published several times in the Netherlands, his native country, initially in 1946, when very few copies were sold. After this first attempt at publication failed, the book fell into oblivion. It was published in France in 2020.

In 1985, Claude Lanzmann made Shoah, a 10-hour documentary film describing the extermination of the Jews, based on eyewitness accounts and footage taken at the scene of the genocide.

Books and films play an important role in resistance, especially those written by survivors or their children. Survival is itself a means of resistance, and by writing books and telling their stories they teach people about what really happened and help to combat the risk of Holocaust denial.

There are now numerous memorial sites in France and throughout Europe dedicated to the victims of deportation and the Resistance movement. In France, in the 1952, a Mauthausen survivor and lawyer, Paul Arrighi, and Annette Lazard, the widow of a man who was deported to Auschwitz and died there, founded the “Réseau du souvenir” (Remembrance Network), which took the initiative to build a memorial to victims of the Holocaust. President Charles de Gaulle inaugurated the memorial, which is in the 4th district of Paris, in 1962 [3]. Since then, many more memorials and study centers have been built, including the Shoah Memorial on rue Geoffroy Lasnier in Paris, which opened in 2005. On March 12, 2024, the Paris Memorial and the authorities in the city of Nice, on the south coast of France, decided to build a second Shoah Memorial Museum in Nice.

Across Europe, several initiatives are underway to preserve the memory of the Resistance and the deportation. The European Parliament, for example, continues to work on Holocaust remembrance[4]; Since 1995, it has passed a series of motions calling for remembrance not only through commemorative events, but also through education. In November 2018, the European Union became a permanent international partner of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). In terms of legislation, the Digital Service Act, which was passed in 2022, is designed to combat online hatred and discrimination, including Holocaust denial.

It is currently considering the idea of erecting a “European monument” in Brussels[5], the idea being to reflect this new approach to Holocaust remembrance, and to involve the whole continent.

The Convoy 77 European project

This Europe-wide project [6] gives schools the opportunity to research and write the biographies of Jewish people wo were deported during the 2nd World War.

Convoy 77, which left Bobigny station on July 31, 1944, was the last major transport of Jews from the Drancy internment camp to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi extermination camp.

1,309 people, including 324 children and babies, were crammed into cattle cars and deported.

The train arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau in the early hours of August 3, and the “selection” was carried out immediately. The official date of death for all of the deportees who were not selected to go into the camp to work was later declared to be August 5, 1944.

At the end of the war, on May 9, 1945, only 251 people who were deported on Convoy 77 were still alive; 847 were murdered in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived.

Spurred on by the advance of Allied troops following the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, and taking advantage of the confusion caused by the failed assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of the Drancy camp, pressed on with his murderous obsession. He was determined not to leave any Jewish children alive, and rounded them up from everywhere he was sure to find them: in UGIF (Union Générale des israélites de France or General Union of French Jews) children’s homes in and around Paris.

More than 300 children (including 18 babies and 217 children between the ages of 1 and 14) were arrested, taken to Drancy and then deported on Convoy 77. Among them were the 20 little girls from the Saint-Mandé orphanage and the manager of the home, Thérèse Cahen, who stayed with them when they were sent to the gas chambers.

For three days, with no food or water and standing up most of the time, Léon travelled locked in a cattle car. As soon as he arrived at Auschwitz, men in gray and blue striped suits made him get out and separated him from the other children: the men had to line up on the left and the women on the right!

The majority of the prisoners (55%) had been born in France, but there were also people of 35 different nationalities. Aside from the French citizens (which included Algerians), they were mainly Polish, Turkish, Russian (in particular Ukrainian) and German.

There were a great many children on this convoy, 324 in total, and 125 of them were under 10 years old.

We took this information from the Convoy 77 website. This non-profit organization plays a vital role both in finding out what happened to the people who lost their lives, and making sure they are never forgotten. The website features work by students from several European countries: we think it would be good if some of them were able to meet each other.

Daniel Naiman

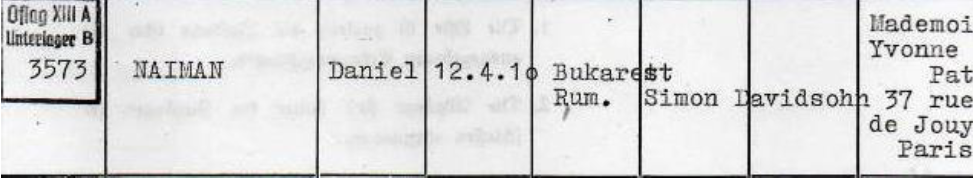

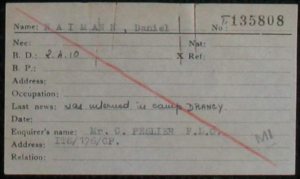

Most of the information about Daniel Naiman comes from the Convoy 77 website and the various records that we studied.

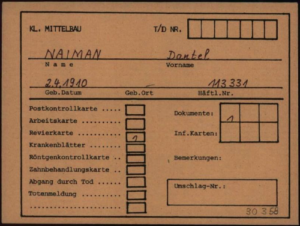

The Arolsen Archives holds a number of records, which they sent to us in January 2024 (requesting that we observe the rules on the use of such material), and there was also a previous biography on the Convoy 77 website.

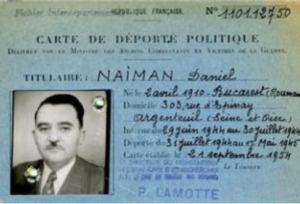

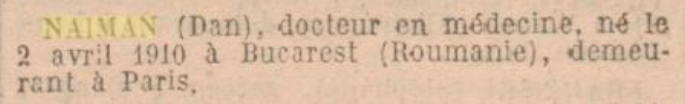

Daniel was born on April 2, 1910 in Bucharest, Romania. According to the Convoy 77 website, his father, Simon, was a merchant, and his mother, Dori Naiman, née Davidsohn, did not work outside the home.

He was naturalized as a French citizen on April 15, 1937, at the age of 27 (Decree published in the French Official Gazette No. 97 dated April 25, 1937, page 4671). Before the war, he lived at 37, rue Barbet de Jouy in the 7th district of Paris. He was a physician at the time.

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service.

Source: French National library (Gallica website: naturalizations, cited by Convoy 77).

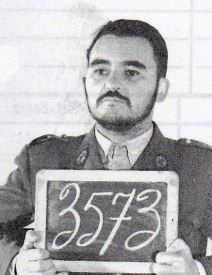

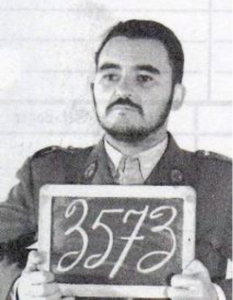

Daniel was mobilized in 1939, and was assigned as assistant physician to the 18th Pioneer Regiment in Nancy, in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France. In 1940, he was taken prisoner at Le Rouge Gazon in Saint-Maurice-sur-Moselle, in the Vosges department, and sent to Oflag XIII A in Nuremberg, where he was assigned the serial number 3573 (as can be seen in the photo above).

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, list of internees.

On January 16, 1941, Daniel was transferred to Frontstalag 194 in Châlons-sur-Marne, in the Marne department of France, pending a decision as to what should happen to the prisoners of war (Frontstammlager were German army prison camps based outside Germany, mainly in France).

He was released in 1941. He married Yvonne Patureau in June 12, 1941 in Paris. The couple relocated to Vichy, in the Allier department of France, which was the main administrative center in the Free Zone. Yvonne had found a job as a shorthand typist at the Ministry of Labor, at 17 rue Alquié in Vichy.

They first stayed at the Colombia Hotel, then at the Belle-Ile hotel, which was annexed to the Plaisance Hotel: all of these hotels had been requisitioned to accommodate Ministry of Labor personnel.

According the decree on the status of Jews, which came into force on October 3, 1940, Jews were no longer allowed to work in various professions, including medicine.

Daniel left Vichy and went into hiding in Cindré, also in the Allier department, some 19 miles from Vichy.

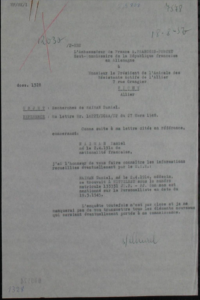

According to a note from the French General Intelligence Service dated April 1, 1954, the French Militia arrested Daniel on June 29, 1944 at the Belle-Ile hotel, while he was visiting his mother-in-law, who was recovering after an operation.

He was interned for two weeks in the Château des Brosses, a Militia-run detention center in Bellerive-sur-Allier, also in the Allier department. On July 15, 1944, he was transferred to Drancy camp, where he was assigned prison number 25,162.

Source: Arolsen Archives

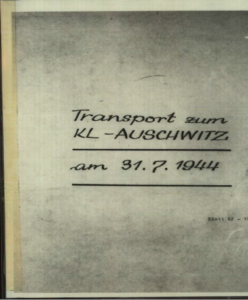

On July 31, 1944 Daniel Naiman was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz aboard Convoy 77.

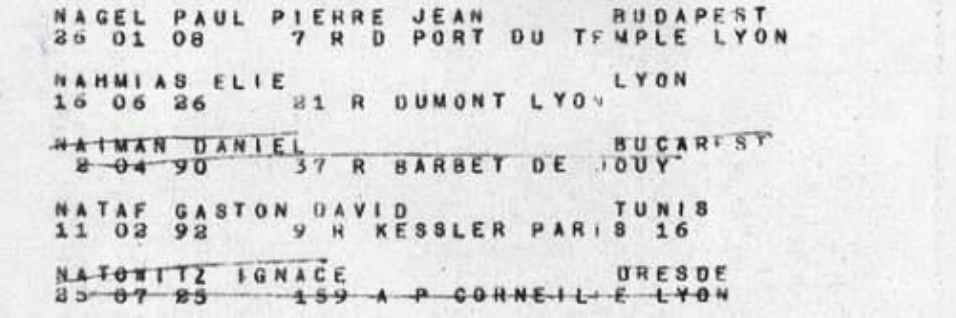

Convoy 77 deportation list. Source: Shoah Memorial, ref. C 77_45.

Source: Arolsen Archives

When he arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944, Daniel was selected to go into the camp to work, and was assigned the number B 3878. According to his testimony, he worked in a number of different Kommando units before being assigned to work in the infirmary.

He was among the men who were transferred to the Gross Rosen concentration camp.

The KL Gross Rosen camp was in Silesia, south of the Oder river, some 60 kilometers from Breslau, near the town of the same name (Rogosnica in Polish). Opened in August 1940, it was initially part of the Sachsenhausen camp, but became an autonomous camp with its own kommandos in the autumn of 1941. In the last few months of the war, prisoners transferred from other camps also spent time in Gross Rosen. These were mainly prisoners from camps in the East, such as Auschwitz, which were hurriedly evacuated as the Red Army was approaching. As a result, Gross Rosen became so overcrowded that a typhus epidemic broke out, and between February 8 and March 23, 1945, the camp was evacuated. Prisoners were sent to KL Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Dachau and, in particular, Dora and its Kommandos, including the Boelke Kaserne in Nordhausen. More than 30,000 prisoners were transported in open-top trains. The death toll was enormous. On May 5, 1945, when the Soviet army arrived in the camp, they found very few prisoners still alive.

Source: Memorial book published by the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation, cited on the Convoy website.

Daniel was transferred to Buchenwald, where he was assigned a different prisoner number, 113331, and was then evacuated to Ravensbrück. He was repatriated to France on May 18, 1945 arriving first at the Valenciennes reception center in the Hauts-de-France department, near the Belgian border.

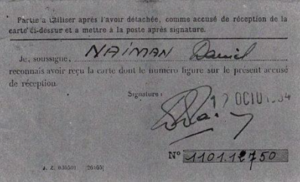

On September 21, 1954, after he was officially recognized as having been deported for political reasons, he was issued a Political Deportee card, number 110112750.

Source: Paris Archives, ref. 3595 W 138.

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service.

According to the French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes (File No. GR 16 P 439315), Daniel was officially certified as having been a member of the R.I.F. (French Internal Resistance). We assume, therefore, that he joined a Resistance network in Vichy and that was the reason that the French Militia arrested him, but he was then deported because he was Jewish rather than as a Resistance fighter.

Unfortunately, we have no more details about his involvement in the Resistance or the circumstances of his arrest.

Source: Arolsen Archives

© Friends of the Allier department Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation

Bibliography

Archive sources

- Allier Departmental archives, refs. 1580 W 9, 1756 W 2 N° 5860

- Paris Archives, ref. 3595 W 138

- French national library, on the Gallica website, list of naturalizations – Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service

- Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine (Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation) – Civil status register, 7th district of Paris

- Serge Klarsfeld – List of prisoners transferred from Vichy to Drancy on July 15, 1944

- Serge Klarsfeld – Memorial to the Jews deported from France, FFDJF 1978

- Memorial book published by the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation

- French Defense Historical service in Vincennes (Dossier GR 16 P 439315)

Articles

- Michel Lafitte’s, L’UGIF, collaboration ou résistance ? (The UGIF, collaboration or resistance?), Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 2006/2 (N° 185), pages 45 to 64.

Websites

- Enfants juifs à Paris, 1939-1945 – L’enfant et la Shoah (Jewish children in Paris, 1939-1945 – Children and the Holocaust) (lenfantetlashoah.org)

- Serge Klarsfeld – Memorial to the Jews deported from France – Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France – Serge Klarsfeld | Fondation Shoah

- Convoy 77 – Teaching the history of the Holocaust in a different way

- CIVS (the French Commission for Restitution of Property and Compensation of Victims of Anti-Semitic spoilation)

Notes and references

[1] In 1975, Serge Klarsfeld began compiling a list of the victims of the Holocaust in France. The first edition of his Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Deportation of the Jews from France) was published in 1978. Since then, he has published a number of other reference works that have furthered our understanding of Anti-Semitic persecution during the war. He also wrote: Vichy-Auschwitz. Le rôle de Vichy dans la solution finale de la question juive en France (Vichy-Auschwitz. (The role of the Vichy government in the Final Solution to the Jewish Question in France) (1983), Le calendrier de la persécution des Juifs de France (Calendar of the Persecution of the Jews of France) (1993) and Le Mémorial des enfants juifs déportés de France (Memorial to the Jewish Children Deported from France) (1994). The most recent edition of the Memorial to the Deportation of the Jews from France, published in 2012, is the culmination of 15 years’ work.

[2] The decree of August 9, 1944 declared that “the form of government is and remains the Republic. In law, it has never ceased to exist”. The aim was to minimize the responsibility of France and the French people for the actions of the Vichy regime, which De Gaulle deemed “null and void” (source: 12th grade students from the Henri IV high school with their teacher, Ms. Morisseau)

[3] Mémorial des martyrs de la Déportation (Memorial to the martyrs of the Deportation) | ONaCVG (The French National Office for Combatants and Victims of War) (onac-vg.fr)

[4] Magdalena Pasikowska-Schnass and Philippe Perchoc, Research Service for MEPs, The European Union and Holocaust Remembrance, European Parliament website, 2020.

[5] Towards a European Holocaust memorial? Touteleurope.eu

[6] Convoy 77 – Teaching the history of the Holocaust in a different way

Français

Français Polski

Polski