What types of documents are available at the SHD-DAVCC?

“These are often civil status records or applications for the status of ‘political deportee’, since this was how Jews were classified when the status was first introduced in 1948,” explains Sandrine Labeau. She adds that the phrase “died during deportation”, which also appears in the records, has existed since 1985. Such files often contain at least one birth certificate and one death certificate, but sometimes also marriage certificates or photographs. They are updated with information provided by families who need documentation and by the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs’ own documentary research.

The SHD-DAVCC also has a collection called “old files”, which include documents issued by the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs even if the family did not submit a request.

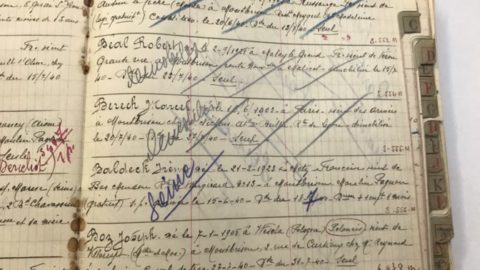

Lastly, there is one more source: the Fichier National des déportés, internés, fusillés et travailleurs (FN) (National Register of deportees, internees, people shot by firing squad and workers) register, set up in 1945 by the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs. There is sometimes little information, but there is at least one record sheet for each deportee.

“All these dossiers and the Fichier National register provide information on places of birth, some addresses and family relationships. This makes it possible to reconstruct part of the personal history of the deportees”, says Sandrine Labeau.

What methodology to follow to make best use of these records?

All the information gathered by Sandrine Labeau and Alexandre Doulut during their own research into the Convoy 77 deportees (date of birth, addresses, date of arrival at Drancy, registration numbers) has been collated in an Excel spreadsheet. “It serves as a starting point for the biography. It can then be expanded with more general background information on the history of the Holocaust” Sandrine Labeau points out.

The historian explains that it is then possible to enhance the research by using the French Departmental Archives of the places where the deportees lived, were interned or arrested, the Shoah Memorial collections, and also, for deportees born abroad, the naturalization files and foreigners’ files (the Fonds de Moscou, or Moscow collection), both of which are held by the French National Archives, or the spoliation records, which are also kept in the National Archives. Finally, the National Archives now have access to the Bad Arolsen archives in digital form (a number of these records are available online).

“One can find photographs, identity cards and addresses” explains Sandrine Labeau. One can either visit or write to the archive services, which can help with research or send scanned records. To complete the research, Yad Vashem Memorial and the Unites States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington websites publish digital databases containing numerous documents.

Where to begin?

Sandrine Labeau suggests that it is useful to start research with the person’s arrest and work backwards from there. For example, by asking the departmental or municipal archives services if they have any records about a deportee or a member of his or her family, which can in turn yield additional information. For people born abroad, who later applied for French nationality, naturalisation files are important sources: applicants listed all their previous addresses, which makes it possible to reconstruct their itineraries throughout Europe and obtain information about whole families

Alexander Doulut and Sandrine Labeau have included in the Excel file, under reference number (AN F9), some testimonies collected by the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs after the survivors’ returned to France. These are kept in the French National Archives. “These testimonies recount the survivors’ stories as well as general information about the camps, but they should be treated with caution: some deportees did not know exactly what was going on in the camps as a whole and they sometimes made mistakes or passed on hearsay. The testimonies must therefore be put into perspective and compared with the work of historians” says Sandrine Labeau.

What should I do if I don’t have many records?

“The information in the table makes it possible to start researching and to draw up a short biography“, Sandrine Labeau explains. She recommends that teachers do some preliminary research using resources in local archives services, the Shoah Memorial and the French National Archives. The specialist archivists at all these places offer invaluable help and can also suggest other collections to look at.

If there is only a limited number of documents, it is not necessarily a problem, as shown by the work of the 9th grade students at Charles Peguy junior high school in Palaiseau. Their history teacher, Claire Podetti, sometimes worked with very few documents : “This too is part of the history of the Holocaust: the desire to make everything disappear, to remove all the evidence. The students understand this very well”. In this case, she widened the scope of the research by addressing cultural aspects of Jewish life before the Second World War from a historical perspective, with reference to literary, artistic and musical material. For example, the students produced a second, dialogical biography to recount the testimony of a deported person’s daughter and imagine the conversations they might have had.

1945- Les rescapés juifs d’Auschwitz témoignent, Alexandre Doulut, Sandrine Labeau et Serge Klarsfeld, Éd.FFDJF- Après l’oubli, 2015.

Further information: Archives: which documentary collections to use in your research?

Français

Français Polski

Polski