Jacques HOLZ

This biography was written by 9th grade students from the “Piaf” class at the Fernand-Léger middle shool in Vierzon, in the Cher department of France, together their teacher, Ms Floride Mahieu, during the 2021-2022 school year.

In order to read the documents in the biography more clearly, click on the images to see them in their original format.

Introduction: research methods

Before writing the biography of Jacques Holz, the 9th grade students from Fernand-Léger middle school in Vierzon first learned all about the Convoy 77 nonprofit organization and read all the information and records provided. They then split up into groups according to themes that they themselves determined: the childhood, deportation and remembrance of Jacques Holz. They chose to write the biography in a historical and scientific manner and to avoid romanticizing or inventing events in his life. One student carried out more extensive research at Nancy City Hall. We also received additional archived material from the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC and lastly, on May 2, 2022, Henri Rosenfarb, Jacques Holz’ cousin, came to the college to speak about his own research. Here is the press article featuring the meeting with Mr. Rosenfarb (on the left of the photo).

“Middle school students confront the tragedy of the Shoah”, Le Berry Républicain, May 3, 2022.

“Middle school students confront the tragedy of the Shoah”, Le Berry Républicain, May 3, 2022.

Mr. Rosenfarb was very emotional as he spoke to the students. He recounted how he had discovered his family history, starting with “a picture that had always been on display in the living room” and ending with the much later discovery of “a box of photos and paperwork in his parents’ house”. He thus embarked on more than twenty-five years of research to reconstruct his family tree and to better understand the events that had affected his family. During his research, he felt “emotion, anger, and then forgiveness”. A number of students in the class presented this topic, their research, and what they had learned and experienced during their oral examinations for the Diplôme national du brevet (which allows students to be admitted to high school). What follows is the result of their work.

Ms. Mahieu, history-geography teacher, school year 2021-2022

1. Jacques Holz: his family and childhood

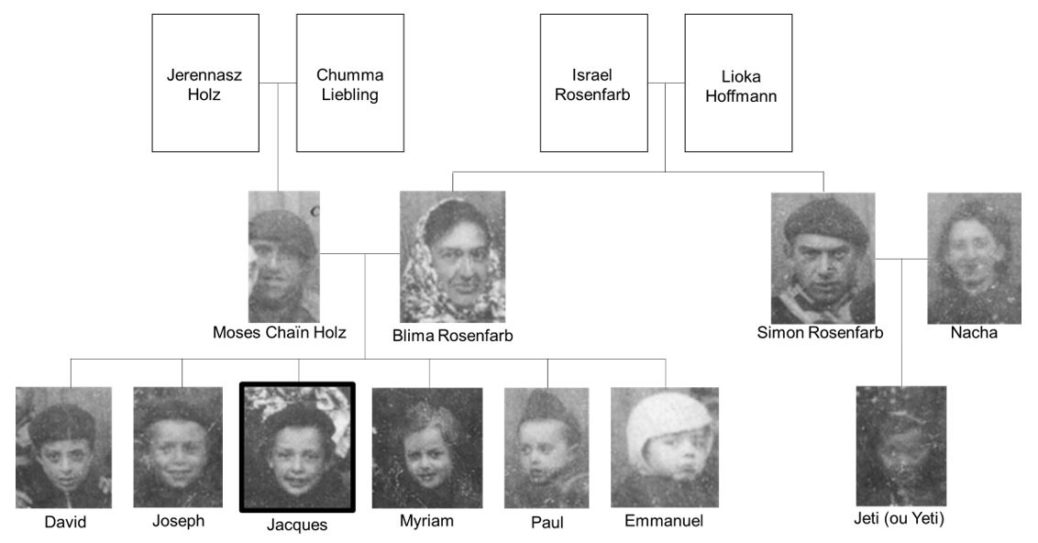

On March 31, 1930, in Nancy, Moses Chaïn Holz, born in 1897 in Mościska, Poland, married Blima Rosenfeld, born in 1902 in Konskie, also in Poland. Moses was a brewery boy at the time and lived at 20, rue des Dominicains in Nancy. He was the son of Jerennasz Holz, a merchant in Mościska, and Chuma Liebling, who had died in 1930. Blima was not working and had been living at 1 place Lafayette since February 1922[1] with her parents, Israel Rosenfarb and Lioka Hoffmann, both of whom were restaurant owners in Nancy[2]. Both families were Jewish. Israel was a very devout man: he performed animal sacrifices and ran a kosher restaurant. Immigration from Poland was quite significant in France, including here in the East. It happened in response to the French government’s attempts to revive the industrial sector, which enabled foreigners to obtain a work permit and gave them the right to reside in France. The rue des Dominicains and the place Lafayette, where the two families lived, were close to the Jewish quarter of Nancy, which was centered around the rue Notre-Dame[3].

After their wedding, Moses and Blima moved to the bride’s family’s apartment at 1 Place Lafayette, where they had their first four children: David (born February 23, 1931), Joseph (born August 26, 1932), Jacques (born December 28, 1933) and Myriam (born August 25, 1935). The 1936 census shows that the family was then living at 47 rue des Ponts, the house where they their last two children were born: Paul (born on June 23, 1937) and Emmanuel (born on March 6, 1940)[4]. Jacques was granted French nationality by means of a declaration submitted on January 16, 1934 before the Justice of the Peace of the Canton of Nancy-Nord (in accordance with article 3 of the law of August 10, 1927)[5].

Here is a family tree showing the people mentioned in our biography who were closest to Jacques:

Family tree showing Jacques Holz’s close family[6]

All of the Holz children went to the Didion School, which was the nearest school to their home. However, we have no further information about the school or their enrollment dates.

2. The deportation of the Holz family

At the beginning of the Second World War, the Prefect of the Meurthe-et-Moselle region decided to expel all foreign nationals, who he deemed to be “a danger to the country”. This decision led to the expulsion of 1,095 Polish Jews. On November 19, 1939, a train took many of these people from the Nancy freight railroad station to Libourne, in the Gironde department of France. They were each allowed to take only about 65 pounds (30 kg) of luggage. The Holz family left in March 1940 in a front-wheel drive Citroën[7]. In November 1940, when the family had to take part in a census, the French government required them to include the fact that they were Jewish (decree dated October 3, 1940)[8].

In December 1940, the family was placed under house arrest in the Vienne department. The Rosenfarb branch was sent to a camp near Poitiers and the Holz branch to the Poitou area. Some of the grandparents were sent to a camp at Mérignac, in the Gironde department. The Poitiers camp, where Jacques went, was initially intended to accommodate gypsies. However, on July 15, 1941, the gypsies were transferred to Orleans and Chinon so that the camp could be used to hold Jews. The living conditions in the camp were very harsh due to overcrowding, skin conditions and digestive disorders. Social workers took some photos of the men, women and children together, notably when they were peeling potatoes. Some of the heads of family groups complained about the lack of food and called for the women and children to be released. A hospitalization record kept at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Poitiers shows that Jacques and his younger brother Emmanuel were admitted for dermatological treatment. Rabbi Elie Bloch, who helped out at the hospital, brought the patients food and clothing. He also took in Jacques and his younger sister Myriam for a while[9].

While they were interned in Poitiers, Blima asked that her children, who were under fourteen years of age and “all French”, be freed and thus protected. The concentration camp forwarded this request from “the Jewish woman Blima Holz” to the prefect in October 1941. Fourteen was a very significant age, since the Nazis were attempting to systematically kill all Jews over the age of sixteen. When Philippe Pétain’s government then proposed to lower the age at which French children could be deported to their deaths to fourteen, Nazi Germany refused to lower the age limit. This meant that French children could be “liberated” because they were below the “age limit” for deportation. Nevertheless, the director of the concentration camp in Poitiers refused: the French camp doctor thought that the children should stay with their mother. Another letter states that the children were not initially going to be sent to the camp, but had to be because there was no alternative care available. Blima’s request was eventually granted, however, and the children were allowed to leave Poitiers to be with their grandparents, who by then had been released from the camp in Mérignac and had moved to the town of Berthegon, about 45 miles (70 km) southwest of Tours. One of the grandparents, Israel was still in the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Poitiers, where he refused to eat and ultimately died of “paralysis” or “melancholy”. Since he was Jewish, he was buried in a communal grave, but Mr. Rosenfarb has discovered that his body was later exhumed and buried, this time with religious rites, in the Jewish cemetery in Nancy[10].

Henri Rosenfarb was able to give us some more information about the children’s stay in Berthegon. The family was housed in the annex of the village castle. During the day, they were not allowed into the school but could go to the courtyard of the local bistro. They are also listed in the local census records.

In 1942, the Nazis intensified their anti-Semitic policies and began to implement the “Final Solution”, which was intended to eliminate all Jewish people in Europe. In March 1942, Moses, Jacques’ father, was assigned to work for the Todt organization in Saintes, probably on the construction of the Atlantic Wall. He was declared unfit for work on June 10, 1942, and was deported on Convoy 8, which left Poitiers and passed through Angers on July 20, bound for Auschwitz. Simon Rosenfeld, Jacques’ maternal uncle, was deported on Convoy 13 from Pithiviers at the end of July 1942 and his wife Nacha was deported on Convoy 14 from Pithiviers at the beginning of August 1942. Jeti (also known as Yétti or Renée), his cousin, Simon and Nacha’s daughter, was deported on Convoy 21 from Drancy in mid-August 1942. She was alone in Drancy for a month, between her arrival on July 21 and the departure for Auschwitz on August 19, 1942. On September 23, 1942, Blima, Jacques’ mother, was transferred from Poitiers to Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 36[12].

3. Deprived of their parents, the Holz children were cared for in the UGIF’s children’s homes

After Jacques’ parents were deported, the Feldkommandantur asked for a list of children whose parents had been interned and who were to be placed in various children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews). Accompanied by Red Cross nurses and escorted by the gendarmes, Jacques, his brothers and his sister were transferred in special cars on the scheduled train from Bordeaux to Paris. They were admitted to the Lamarck Center on April 20, 1944, a building that had been refurbished after a bombing as a reception center for orphans, and then to the Lucien de Hirsh school. The children were placed in three different UGIF homes: Myriam and Paul were sent to the Louveciennes home (at 18 rue de la Paix)[13], David, Jacques and Joseph to the Secrétan center (at 70 avenue Secrétan in the 19th district of Paris)[14] and Emmanuel to La Varenne (now Saint-Maur-des-Fossés)[15]. A letter written on a sheet of from a school notebook describes their daily lives, including a birthday where David was given a pencil and Emmanuel got some sweets. The children’s home organized drama classes and the children participated in shows. Jacques was ranked eleventh in his class[16].

4. The round-up and deportation of Jacques Holz

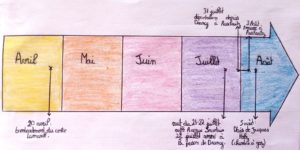

During the night of July 21-22, 1944, the three UGIF homes where the children were staying were raided. Jacques Holz, a totally ordinary child who just happened to be Jewish, was rounded up along with the others. He was interned 10 in Drancy camp when he was just ten years old. He was imprisoned along with many other people who were to be deported. They were aware that they might be taken to a concentration camp or a killing center. The living conditions in the camp were terrible: the people had little to eat and the sanitary facilities were deplorable. On September 20, 1944, a letter from the UGIF stated that the organization had no news of those who had been rounded up and that everyone had been sent to an “unknown destination”[17].

On July 31, 1944, Jacques Holz was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, gave the order to deport him in retaliation for activities carried out by the Resistance. It was the last convoy to leave Drancy for the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and was supervised by both French and German police. The group was deported from Bobigny railroad station and the journey lasted four days. Jacques did not travel on his own; he was always with his brothers and sisters. He arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944, during the night. When they arrived, all the people in the convoy, children and adults, were forced to undress and then held in barrack huts[18]. After two horrific and interminable days, Jacques was finally murdered in the gas chambers[19]. He was just 10 years old at the time. Jacques Holz was killed in the same atrocious way as most of the Jews during the Second World War.

Timeline of the Jacques Holz’s deportation (year 1944)

Timeline of the Jacques Holz’s deportation (year 1944)

5. After Jacques’ death

The only surviving members of Jacques’ family are two uncles: Samuel and Maurice, who was Henri Rosenfarb’s father. After Jacques Holz was deported, the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War in Paris issued a missing person certificate dated June 22, 1955, and sent it to his uncle Samuel, who was still alive at the time[20]. Maurice Rosenfarb’s name is included as a reference on the cover of Jacques’ Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War record entitled “Civilian victim. Death dossier”.

Jacques Holz was acknowledged to have been a civilian victim of the Second World War and in 1995, he was granted the status of “died during deportation”.

During the course of his research, Henri Rosenfarb filed a testimonial form with Yad Vashem, the International Institute for the Remembrance of the Shoah in Jerusalem. He visits secondary schools to pass on the history of his family. He does not see this as a duty but as “remembrance” and as a way to pay tribute to the victims[21].

Sources

[1] Nancy City Hall, municipal census, 1 F.

[2] SHD, 21 P 258433, Jacques Holz’s death dossier, letter from the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War dated November 9, 1972; Nancy City Hall, civil marriage certificate of Moïse Chaim Holz and Blimat Rosenfarb, 3 E 348.

[3] Henri Rosenfarb’s testimony, Fernand-Léger middle school in Vierzon, May 2, 2022.

[4] Nancy City Hall, municipal census, 1 F.

[5] SHD, 21 P 258433, cover of Jacques Holz’s death dossier.

[6] Photos taken from a family photo provided by the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

[7] Henri Rosenfarb’s testimony, Fernand-Léger middle school in Vierzon, May 2, 2022.

[8] Légifrance, “Law of October 3, 1940 on the status of the Jews”, Journal officiel de la République française dated October 18, 1940:

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000000869361/ (site viewed on June 18, 2022).

[9] Henri Rosenfarb’s testimony, Fernand-Léger middle school in Vierzon, May 2, 2022.

[10] Ibidem.

[11] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=jacques%20Holz&spec_expand=1&start=0

[12] https://www.yadvashem.org/fr/recherche/convois-de-france.html

[13] “Rafle de Louveciennes”, in French only Wikipédia:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rafle_de_Louveciennes (site viewed on June 18, 2022).

[14] “Rafle de l’avenue Secrétan”, in French only, Wikipédia:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rafle_de_l%27avenue_Secr%C3%A9tan (site viewed on June 18, 2022).

[15] “Rafle de La Varenne”, in French only, Wikipédia.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rafle_de_La_Varenne-Saint-Hilaire (site viewed on June 18, 2022).

[16] Henri Rosenfarb’s testimony, Fernand-Léger middle school in Vierzon, May 2, 2022.

[17] Ibidem.

[18] “History and make up of the convoy”, Convoi 77. https://en.convoi77.org/history-and-make-up-of-the-convoy/ (site viewed on June 18, 2022).).

[19] The date of Jacques’ death, set by court « judgement », was August 5, 1944. SHD, 21 P 258433, ” Death certificate,” Berthegon Town Hall, true copy dated October 23, 1972 of a record made on August 20, 1955 following the hearing of the Civil Court of First Instance of Loudun on July 27, 1955.

[20] SHD, 21 P 463 869, Missing person’s certificate from the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War dated June 22, 1955.

[21] Henri Rosenfarb’s testimony, Fernand-Léger middle school in Vierzon, May 2, 2022.

Français

Français Polski

Polski