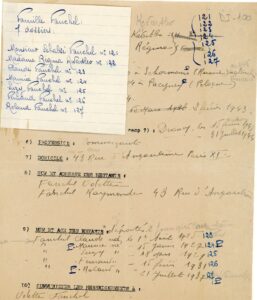

Schabse FANCHEL

Schabsé Fanchel and his family, 1880-1944, Convoy 77

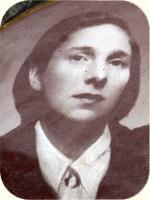

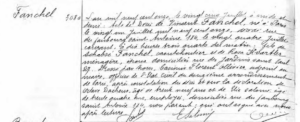

Photo of Schabsé. Source: the French genealogy website, Généanet

In the winter of 2004, a little over 20 years ago, I asked Ida Grinspan to come and speak to my ninth-graders. At the time, I was a young history teacher at a suburban middle school.

During her visit, Ida spoke with one of my students, Andersen Nshimiye, a 19-year-old Tutsi miner who had lost his father, who was killed in Rwanda, and whose family had become scattered. They talked at length, both survivors of contemporary genocide.

For many years now, driven by my keen interest in microhistory, I have been working on local history projects with my students, in partnership with my colleague, Aurélie Trinkwell. The projects covered topics including: the story of the last World War I veteran from Brévannes, the resistance movement in the town, my husband’s compilation of a database on deportees from Brévannes and, more recently, the Convoy 77 project, and the Fanchel family, for which he carried out extensive research in various Paris city archives.

Between October 2024 and January 2025, the students from class 4eC worked on the biography of Schabsé Fanchel, a father of nine, who was deported on Convoy 77, the very same convoy that led to the death of Ida Grinspan’s father.

I wanted to share with the class the results of several years of research, not only to help them become familiar with the methodology of searching for archived records, but also to engage with the history of their local area and see it in the context of migration on a global scale.

It was also, in a way, about preserving the history of the Fanchel family, as none of its members are still alive.

The question the students were asked to address as part of the project was:

How might past and present migratory patterns and people’s individual journeys help us better understand our local area?

In 2019, the Convoy 77 project team sent me three names: Nathan Potzeha, Regina Potzeha et Schabsé Fanchel.

Nathan and Regina’s names are inscribed on the local war memorial alongside the words “Died for France.” Schabsé’s name, however, is not listed.

My husband and I thus began to research Schabsé’s story, as well as that of his family. It mirrors the migratory journeys of many Eastern European families driven from their homelands by anti-Semitism.

Who was Schabsé?

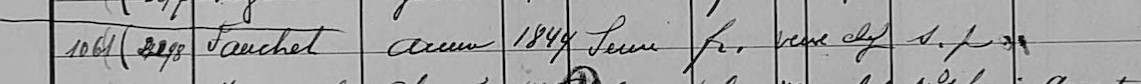

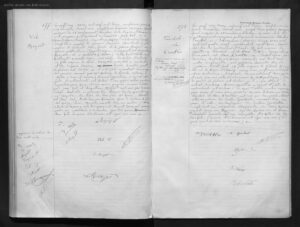

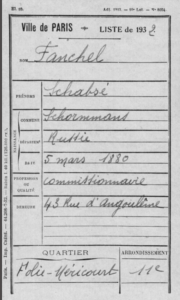

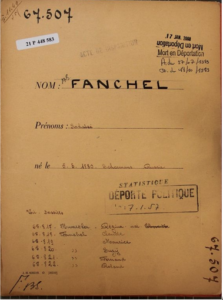

Schabsé Fanchel (the father of the family), was born on March 5, 1880 in Schornmans, in Russia.

His parents, who came to France with him, were Mathous Fanchel and Hona, or Anna, Tokar.

In 1936, his mother was living at 27, rue des Jardins Saint-Paul in Paris.

Source: 1936 census, Paris city archives

This name is listed in the Bagneux cemetery burial register for late summer 1940.

Source: Paris city archives

Schabsé had various jobs: rubber worker, fabric and scrap metal dealer, and errand boy.

There is no record of exactly when Schabsé arrived in France, but he had his first child in 1911 and got married in 1913.

Source: Paris city archives, 1913.

He and his wife probably spoke Yiddish, given that an interpreter was present at their wedding. He enlisted voluntarily to fight in World War I[1]. According to Esther Benbassa[2] in her book Histoire des juifs de France, (History of the Jews in France), published by Seuil (“Points. Histoir »e collection), 1997, p. 251, cited by Anaëlle Riou; From Convoy 77, seven men of Jewish faith and foreign nationality voluntarily enlisted in the French Army or the Foreign Legion during World War I: Barouch Alazraki, Sol Ange, Sigismond Bloch, Joseph Brodsky, Nissim Cambi, Schabsé Fanchel and Maurice Marian.

Philippe-Efraïm Landau’s article on Les Juifs russes à Paris pendant la Grande Guerre, cibles de l’antisémitisme (Russian Jews in Paris during the Great War, targets of anti-Semitism, published in the review Archives juives (Jewish archives) in 2001, sheds light on this: “The mistrust, even underlying hostility, toward the 30,000 Jewish migrants from the Russian Empire living in Paris certainly did not begin with the war. It had been apparent since the previous decade, when they arrived in the capital in large numbers. Like other foreigners, simply registering with the police or the town hall, in accordance with the decree of October 2, 1888, allowed them to reside on French soil, look for work, and integrate...[…]

The Russian Jews, who fled the anti-Semitic policies and violence in the Tsarist Empire, settled in various areas of Paris. Over 60% of these migrants found work in small-scale clothing production—including caps, clothing, and fur—mainly concentrated in the Marais district and, to a lesser extent, in Montmartre. […] Any able-bodied man who was a subject of an Allied power had the choice of returning to his country to serve it, or enlisting in France. As a result, Russian battalions were founded, but although they were popular with the French public, very few Jews joined them. […] Unwilling, clearly, to join the Czarist army, even if only symbolically, they nevertheless expressed a strong desire to serve the country that had taken them in, because France still represented an ideal. Many of them saw the war as just and a means of liberation, and believed it would bring down Russian autocracy, as reflected in this rallying call in August: “We, Russian socialists, let us join the ranks of the French army. The defeat of Germany and Austria will inevitably be a triumph and will strengthen democracy.” […] Once the nation’s citizens had been mobilized, foreigners could sign up to serve voluntarily for the duration of the warby virtue of the decree of August 3. Starting on August 24, several thousand Jews signed up, accounting for approximately 8,500 of the total 31,000 foreigners who enlisted. On the first day, of the 1,560 enlistment requests, around 900 were submitted by Russian Jews. In the capital, 27 enlistment committees were established, each to deal with a particular minority group. Of the four Russian committees, two were set up by Jews. In the heart of the Saint-Gervais district, Amédée Rothstein, Jacques Schapiro, and Haïm Cherschevski founded the committee on Rue de Jarente, which recruited nearly 3,000 people, including 2,000 Russians.

Another article, by Philippe-Efraïm Landau entitled, Frères d’armes et de destin. Les volontaires juifs et arméniens dans la Légion étrangère (1914-1918) (Brothers in arms and in destiny. Jewish and Armenian volunteers in the Foreign Legion (1914-1918)), published in the review Archives juives (Jewish archives) in 2015, explains in more detail what happened to the Russian Jewish volunteers: It was thus on the basis of the war’s promise of emancipation and their deep respect for France that these migrants, despised and massacred in their homelands, rallied together and were prepared to sacrifice themselves for a nation that had treated them, according to Yechiel Kogan, “like its own sons”. As they marched around the Place de la Bastille and the Parisians cheered them on with cries of “Long live the Russians! Long live the Jews!“, several hundred people distributed leaflets in Yiddish and French, in which the enthusiastic crowd could read: “Brothers! Now is the time to pay tribute and show our gratitude to the country where we found spiritual freedom and material prosperity.” […] Russian-Polish and Romanian Jews shared this attitude. Before he was killed in action on May 9, 1915, in Neuville-Saint-Vaast, Léon Litwak wrote in his last letter to his friends: “In an hour’s time, we shall march forth for France, for the Jews. Long live the Republic, long live free, noble, and democratic France.” He was disappointed, however, by the lack of press coverage of the atrocities that the Russian troops were inflicting on the Jewish civilian population. But the sacrifices these volunteers made little impression on their superiors and the people back home. Soon placed under the command of non-commissioned officers from the French Foreign Legion who came from Algeria and were deeply prejudiced against them, they suffered constant humiliation. Ruben Bercovici, for example, heard an officer in a trench accuse the Jews and Armenians of volunteering so they could “get their mess tin, and gobble down their rations”.

Schabsé was naturalized as a French citizen in 1925. We are still waiting to see his naturalization application file.

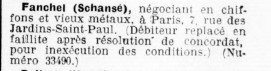

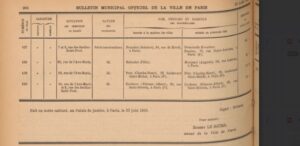

Fanchel Schabsé, rag dealer, born on March 5, 1880, in Schornmans, Russia, residing in Paris. This confirms that he was naturalized. Source: Paris city archives,1925.

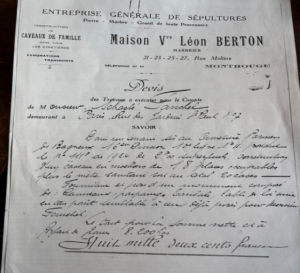

In 1926, he was living at 7, rue des Jardins Saint-Paul in Paris, as evidenced by this order form for a burial plot in Bagneux cemetery.

Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission.

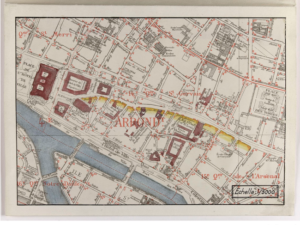

He and his wife Regina (Rosa), lived at several addresses in Paris, and sometimes occupied more than one at the same time: 27, rue des Jardins Saint-Paul, then, 18, Rue de Rivoli and lastly 43, rue d’Angoulème (now rue Jean-Pierre Timbaud).

His name is on the electoral roll for 1932, so he must have been eligible to vote.

Source: Geneanet and Paris city archives.

The couple also had a house in Brévannes, at 9, avenue Allary.

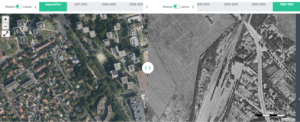

Source: The French National Geographical Institute (IGN) “go back in time” website

It would have been quick and easy for them to come and go between Paris and their country home by train via the former Paris-Bastille station.

Source: Limeil-Brévannes municipal archives

Below are two images of the Allary Avenue neighborhood, one as it was after World War II and the other as it is today:

Source: The French National Geographical Institute (IGN) “go back in time” website

Source: The French land registry cadastral plan

The couple gave all of their children French-sounding first names: Vincent, Isaac, Berthe Odette, Claude, Suzy Clara, Maurice, Fernand, Roland and lastly, little Raymonde.

Some of them were born in Paris, others in Brévannes, which again shows that the family lived between two homes.

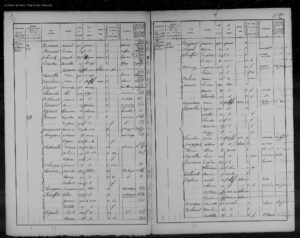

According to the 1926 census, Schabsé and Rosa were then living with Schabsé’s mother, Onna or Hona, on Rue de Rivoli in Paris:

Source: 1926 census, Paris city archives

They were also listed, that same year, at 43, rue d’Angoulème:

Source: 1926 census, Paris city archives.

The couple got divorced in 1929 but carried on living together and had several more children.

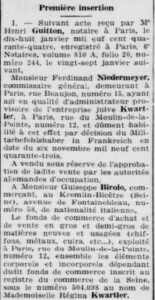

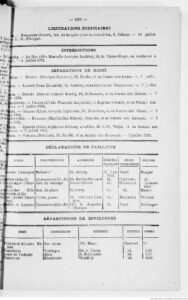

Schabsé’s businesses sometimes got into financial difficulty, as evidenced by his going bankrupt twice and entering into a debt settlement agreement.

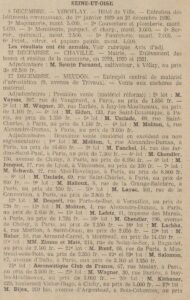

Source: Collection of administrative acts from the Prefecture of the Seine department, Gallica, 1927

Transcription: Paris, August 17: Schabsé Fanchel, scrap metal, rags, 7, rue des Jardins Saint-Paul, 50% with no interest, 10% six months after debt arrangement approval, 10% 6 months after this first payment, 10% on each of the three following years.

The bankruptcy in 1929 (October 25, 1929)

Source: Collection of administrative acts from the Prefecture of the Seine department, Gallica

Jaya’s comment:

This 1929 record refers to the bankruptcy of S. Fanchel’s company. It explains that when companies go bankrupt, they can settle their debts. He was a rag and scrap metal dealer on Rue des Jardins Saint-Paul in Paris (French National Library archives).

In 1929, he bought two lots at 14, rue des Jardins Saint-Paul at an auction in Paris:

Source: Collection of administrative acts from the Prefecture of the Seine department, Gallica

In 1928, he was listed in the business directory (Bottin Didot).

Source: Paris city archives

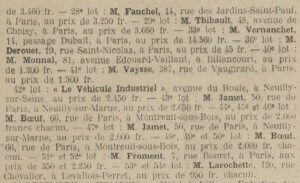

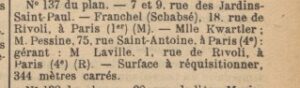

He thus owned his business premises at 7 and 9 Rue des Jardins Saint-Paul, and he and Regina also owned some rented-out apartments (as can be seen from the building’s population census records for 1932 and 1936), which were confiscated in 1942. They owned the building, there is no record of whether or not they received any compensation payment for it.

As this building was part of block 16, Schabsé and Regina lost ownership of it after it was seized. We think the family then went to live in Brévannes, as Isabelle Backouche explains in her book Paris transformé. Le Marais 1900-1980 (Paris transformed, the Marais district 1900 – 1980), published by Créaphis. She describes the redevelopment plan for block 16 as a combination of public policies that ranged from improvements to sanitation to the stigmatization of Jewish families.

The property requisitioned in 1942

Source: Collection of administrative acts from the Prefecture of the Seine department, Gallica

The property confiscated in 1943

Source: Collection of administrative acts from the Prefecture of the Seine department, Gallica

Kylian’s comment:

This is a record of confiscation of property at 7 and 9 rue des Jardins Saint Paul from Schabsé and Régina Fanchel. Two other properties are also listed: 18, rue de Rivoliin in Schabsé’s case and 75 rue Saint Antoine in Regina’s. It dates from June 1942 and came from the French National Library (BNF).

Source: Isabelle Backouche

Shabsé’s wife, Régina, who was deported on Convoy 47 on February 11, 1943

Source: Geneanet

Schabsé’s wife, Régina Fanchel, née Régina or Rosa Kwarlter or Kvarlter, whose parents were Faïvel Kvartler and Haya Fredering, was born on November 11, 1884 (some records state 1904) in Pachetchina-Nadrovna or Pachetchna-Nadrovna (now Pasieczna) in Poland or Austria depending on the records. The Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen hold a file on her, ref. AC 21 P 471 025.

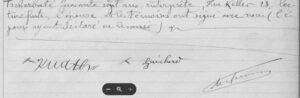

When she married Schabsé, at 9.50 a.m. on March 25, 1913 in the town hall of the 4th district of Paris, she was living 27, rue des Jardins Saint Paul. She was not working at the time.

The witnesses to the marriage were Emile Guichard, age 52, a waiter; Isidore Golstein, 28, a mechanic; Pierre Xavier, 72, an upholsterer and Haïm Tcherbaté, 47, an interpreter. Schabsé was unable to sign his name on the marriage certificate, but his wife signed hers.

Source: Paris city archives

In 1923, the couple stayed at the Hôtel de Bagnoles in Tessé-la-Madeleine, a spa town in the Normandy department of France:

Source: Paris city archives

Regina and Schabsé signed an agreement to separate their property in 1924:

Source: Paris city archives

Regina-Rosa was naturalized as a French citizen on February 6, 1925.

Source: Paris city archives

In 1927, she bought a butcher shop from the Tokar family (Schabsé’s mother’s family):

Source: Paris city archives

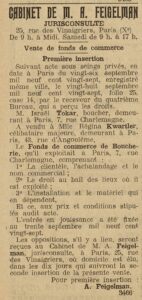

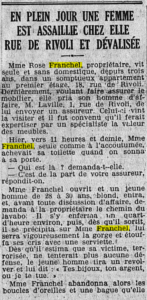

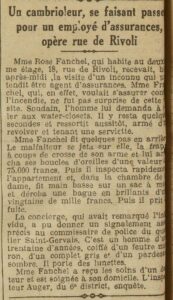

She appears to have lived a fairly affluent life, judging by this report in the newspaper L’Oeuvre on January 6, 1928, which says that she had her earrings and a valuable ring stolen by a man posing as an insurance salesman.

Source : Gallica.

Source : Gallica.

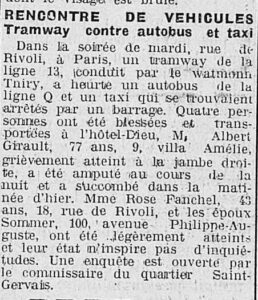

In November 1928, she was injured in a road accident, reported in the Le Petit Champenois newspaper:

Source : Gallica.

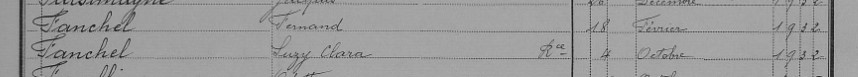

The couple got divorced on April 15, 1929, but continued to live together. In the 1932 census, she was still listed as living at 43 rue d’Angoulême. Her children are listed under her maiden name (as she was divorced) and her birth year is incorrect.

Source: Paris city archives

She was still living there in 1936:

Source: Paris city archives

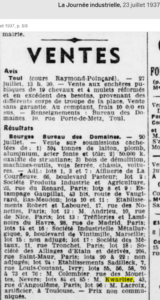

According to the newspaper La Journée industrielle, she bought some goods at auction on July 23, 1937.

Source: Gallica

In early 1942, more anti-Jewish legislation was passed in the occupied zone and ever more extreme policies were introduced: roundups became more frequent.

Claude Singer, a historian at the University of Paris I (DUEJ), in his article Les grandes rafles de Juifs en France (The large-scale roundups of Jews in France), wrote:

As of summer 1942, all Jews in France, regardless of gender, age, or nationality, came under threat. The threat was very real, as in most cases, arrests resulted in deportation to an unknown destination outside the country. The public was unsettled by this radicalization, and voiced its disapproval. How could people condone the succession of horrific scenes that occurred during the roundups, in particular the young children’s screaming and crying as they were torn away from their parents? […] In 1943 and 1944, arrests, roundups and deportations continued in Paris, and in the both the occupied and southern zones. In total, between March 1942 and August 1944, 75,000 Jews were deported from France. The majority were foreign Jews, but around a third of these men, women and children were French Jews. The German authorities did not differentiate between French and foreign Jews. For Nazi Germany, all Jews, regardless of age or nationality, were targeted for deportation and extermination.

Even French citizens, such as the Fanchel family, were therefore at risk.

Regina was arrested in Brévannes on February 2, 1943 (the same day as von Paulus surrendered in Stalingrad), interned in Drancy camp along with Claude, Maurice, Fernand, Suzy, Roland and little Raymonde, and subsequently deported.

The following passage, taken from the 1978 edition of Serge Klarsfeld’s Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Jews deported from France) explains how they were sentenced to death. The lists of names of people deported on the convoys were updated by Jean-Pierre Stroweis.

The transports were suspended for nearly two months. In December, Eichmann and the Sipo-SD in France reviewed the situation and the prospects for deportation in early 1943. On December 31, Knochen telegraphed Eichmann to say that deportations would resume in mid-February, but he was unable to say exactly how many Jews would be involved. But then, on January 21, 1943, Knochen cabled Eichmann again. He asked him what transport options were available for 1,200 Jews who were ready to be deported. He told him that 3,811 Jews were interned in Drancy, including 2,159 French Jews. Then he asked the crucial question: could French Jews be deported?

On January 25, Eichmann’s deputy Günther replied that the Reich Ministry of Transport had given the go-ahead to transport 1,500 to 2,000 Jews from Drancy to Auschwitz in freight cars. On the deportation of French Jews, Günther cabled saying there was no objection, as long as it was carried out in accordance with the guidelines for the evacuation of Jews from FranceHe also said that the escort from Drancy to the border of the Reich would be handled by an SD commando from Metz, and that from the border onwards, the Ordnungspolizei (order police) would take over and escort the convoy to Auschwitz. On January 26, Knochen sent a telex to all regional Gestapo offices: arrest all Jews subject to deportation and transfer them to Drancy. […]

On February 3, Röthke, the head of the Gestapo’s anti-Jewish department, sent a telex to Eichmann’s office at the RSHA in Berlin saying that on February 9 and 11, two trains were to leave for Auschwitz at 8:55 a.m. carrying around 1,000 Jews. On February 5, Röthke sent a telex to the Ordnungspolizei stating that three convoys were scheduled and that escort commandos of 12 to 15 men should be made available. On the same day, Röthke asked the Gestapo in Dijon to transfer all Jews in their custody so they could be deported on February 9 and 11. The day after the February 9 convoy left, Röthke, head of the Gestapo’s anti-Jewish department, wrote a detailed memo, which was initialed by the recipients, Knochen, head of the security services and the security police, the Sipo-SD, and General Oberg, head of the SS and the German police in France [XXVc-204].

In the memo, Röthke stated: 837 French Jews were interned in Drancy following the roundups of December 1941 and 1942, in addition to 661 French Jews who had broken the law. The Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) gave the green light for further transports of 1,000 Jews on February 9, 11, and 13, 1943.[…] Meanwhile, the second convoy was to depart with 1,000 Jews who were either stateless or held nationalities that made them liable for deportation. The third transport, on February 13, was to be made up of French Jews who had committed crimes and were interned in Drancy. In addition, by February 11, the French police wanted to intern some more “deportable” Jews, i.e., foreigners, caught during a series of small roundups. The French police made this request of their own accord because they were keen to stop French Jews being deported. French police representatives told Röthke that the matter of deporting Jews who held French nationality had not yet been settled between the French and German governments. As a result, the French police would not help to deport French Jews, even those punishable by law, until this issue had been resolved. Röthke concluded his memo as follows: “I replied to these gentlemen that I found this view surprising, given the fact that in 1942, we had already deported some French Jews who had contravened the laws applicable to them. Sauts (an associate of Prefect Leguay, who served as the representative of Bousquet, the Vichy Secretary of State for the Interior in the occupied zone) further stated that, in Bousquet’s view, we could deport the French Jews held in Drancy, but that the French police would be unable to assist us. After a decision made during a telephone conversation with the BdS (Knochen), I told Sauts that the transport planned for February 13 would go ahead regardless. I will submit another report to the RSHA this evening on the transport issue”.

After Germany was defeated in Stalingrad and the tables were turned, the Vichy government became more cautious in its anti-Jewish collaboration with the Nazi police. They were reluctant to support the deportation French Jews, who, in the event of an Allied victory, could hold them responsible more effectively, both legally and morally, than could the families of foreign Jews, who left behind fewer links with the French nation. This explains not only Vichy’s reluctance to deploy French police officers in plain sight at the departure points for transports carrying French Jews, but also the sheer cynicism of its policy of rounding up more foreign Jews in order to prevent French Jews from being deported. As Knochen wrote in his telegram report to Reich Gestapo chief Müller on February 12, regarding “the final solution to the Jewish problem in France,” in order to save French Jews from being deported, French police had spontaneously arrested 1,300 foreign Jews on February 11, and they would be deported along with the French Jews.

The second convoy in February, on the 11th, was thus made up mainly of foreign Jews. We have identified 372 Poles, 154 French (mostly children born in France to foreign parents), 109 Russians, 65 Dutch, 64 Romanians, 56 Germans, 41 Turks, 40 Greeks, 32 Hungarians, 20 Czechs, 16 Austrians, 15 Belgians, 10 Bulgarians, and a few others, even including a Jewish woman born in Poland and now a Chinese citizen by marriage. We counted 499 men, 477 women, and 22 of unknown gender. There were 175 children under the age of 18, including 123 under the age of 12. 172 deportees were over the age of 60 (elderly people were taken from nursing homes and brought to Drancy on February 10, at the same time as the children, to make up the numbers).

A routine telex sent to Eichmann and Auschwitz, dated February 12, stated that at 10:15 a.m. the previous day, a transport had left the Bourget/Drancy station for Auschwitz, carrying 998 Jews. The man in charge of escorting it was Oberleutnant Kassel, of the Schutzpolizei, and on February 14, he wrote a report about escape attempts that took place before the train reached French border. List No. 47 is in very poor condition. Many names are almost illegible because the characters have been erased from the thin paper. There are 9 sub-lists:

- Romainville: These must have been foreign Jews who had broken the rules or were suspected of acts of resistance and were transferred from Fort Romainville to Drancy.

- Romainville – French: 16 French citizens, as above.

- Compiègne foreigners: 12 men transferred from the Compiègne camp to Drancy.

- Compiègne – French: 39 men.

- Drancy – 1: 56 people, including numerous families, such as Abraham and Mirla Checinski, aged 48 and 46, and their four children, Wolf, 16, Simon, 14, Elly, 11 and Anna, 8.

- Drancy – 2: 745 names, 79 of them crossed out, so 666 who actually left. Numerous families, most of whom had French children: Henri Ajzenberg, aged 3; Maxime Borenheim, 3; Jeannette and Hélène Diamand, 4 and 2; Samy Grin, 9; Joseph Haber, 8; Tony Jakubovitch, 5; Hélène and Simone Zawidowicz, 8 and 6; Anna and Lucette Klein, 6 and 3; Michel Zelicki, 1; Gilles Lewinger, 1; Madeleine Wais, 1; Claudine Malach, 3; Micheline Muller, 1; Germaine and Pierre Roth, 7 and 3; Jacqueline Kravtchik, 2; Elie and Colette Salomon, 9 and 2; Myriam and Abel Sluizer, 5 and 2. Among the other families: Elie and Mathilde Azouvi, aged 50 and 39, and their three children, Eva, 17, Louisette, 14, and Gaston, 12; Samuel and Gracia Beraha, aged 46 and 37, and their three children, Albert, 9, Michèle, 8, and Monique, 4; Georges and Nesca Erdelyi, aged 34 and 31, and their three children, Betty, 4, Michèle, 3, and Annie-Rose, 2; Doudou Eskenazi and his four children, Rose, 13, Allegra, 10, Albert, 7, and Leon, 5; Perla Goldsztajn, aged 30, with Micheline, aged 2, and Françoise, aged 1; Moise and Perla Kavayero, aged 45 and 43, and their five children, Sarah, aged 19, Esther, aged 17, Elie, aged 14, Diamante, aged 10, and Suzanne, aged 6; Laja Kuperberg, aged 35, and her three children, Fajga, aged 13, Esther, aged 9, and Henri, aged 1; Djaya Lerea, aged 34, and her three children, Rebecca, aged 12, Esther, aged 8, and Isidore, aged 4; Sarah Namer, 47, and her four children, Maurice, 18, Dona, 15, Claire, 12, and Fanny, 9; Sarah Semel, 34, with Salomon, 2, and Isabelle, only 9 months old; Louise Szwarcbart and her baby Bernard; Zurek and Golda Wapniarz, both 42, and their three children, Regina, 8, Robert, 3, and Joseph, 1.

- Drancy – 3: 67 departed. Among the children were Georges and Fernande Blachmann, aged 4 and 2; Berthe and Denise Lemel, 13 and 9; Lucienne Porjes, 1; and Blanche Skrzydlak, 9.

Although she was on the deportation list for Convoy 47, Denise Lemel, who unlike her sister was born in France, was able to leave Drancy. However, she was arrested again and deported on Convoy 77 in 1944.

8. Hospitals – Hospices – Orphanages: The Nazis filled the lists with sick, insane, and elderly people, as well as small children, all mixed together in this list: Theodore Bakra, 83; Gitel Mendelevitch, 91; Esther Krimer, 84; Caroline Neumann, 82; Bertha Schmulevitz, 85; Kiva Makline, 80; Gitla Wajselfisz, 84; Fania Krilitchevski, 87; Marie Dreyfuss, 86; Maria Kohn, 80; Peisach Linker, 70; and 15 other septuagenarians. Among the children were Edith Becker, 12; Sarah Beznovennu, 11; Berthold Bodenthal, 9; Marguerite and Simon Bogaert, 14 and 8; Ruth Buntmann, 10; Esther Don, 11; Jacques Fiszl, 4; Victor Grumberger, 6; Emile Huber, 12; Gaston Kahn, 7; Marie-José and Henri Klayminc, 14 and 10; Leib Kuzka, 10; Sarah Lerer, 13; Joseph, Zelman and Jeanine Lipschitz, aged 11, 8, and 3; Gisèle Messinger, 12; Joseph and Augusta Skoulsky, aged 10 and 5; Mina, Lola, and Simone Sternchuss, aged 9, 6, and 4.

9. Last minute additions list: 19 people.

The travelling conditions were so appalling that one of the deportees, Linda Geber, aged 64, died on the train in the Le Bourget/Drancy station, according to a handwritten note added to the convoy list by Röthke. When the convoy arrived in Auschwitz, on February 13, 143 men were selected to work and were assigned the numbers 102139 to 102280, as were 53 women, numbers 35290 to 35342. Everyone else was gassed immediately. In 1945, there were only 10 survivors, one of whom was a woman.

This convoy was made up of 314 people born in Poland, 156 in France, 81 in Ukraine, 57 in Germany, 56 in the Netherlands, 44 in Turkey, 43 in Romania, 40 in Greece, 29 in Belgium, 27 in Hungary, 17 in Russia, 16 in Belarus, 13 in Lithuania, and 12 in Bulgaria, with the borders as they stood in 2021.

Devan’s comment:

Regina Kwartler was born on February 24, 1904 (?) in Poland. She married Schabsé Fanchel, with whom she had 7 children. The family lived at 9 avenue Allary at Limeil Brévannes. She was arrested on February 2, 1943, interned in Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz on February 11, 1943 on Convoy 47. The children were deported on Convoy 48 and her husband on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

Regina’s name is on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, on slab N°27, column N°, row N°3.

Her death was transcribed from a judgment into the town hall records in Brevannes on December 13, 1950, and signed by the mayor, Marius Dantz. On November 14, 1986, the French government awarded Regina the official status of “Died during deportation”.

The two sons who died, Vincent and Isaac

Vincent Fanchel, July 21, 1911 – July 24, 1911

Source: Paris city archives.

Isaac Fanchel, September 27, 1914 – June 6, 1915

Source : archives municipales de la ville de Paris.

Isaac Fanchel 27/09/1914 – 6/06/1915

Source: Paris city archives.

Isaac’s body lies in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris. He was buried there in 1926 when his father built the family vault.

Source : Geneanet.

Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission.

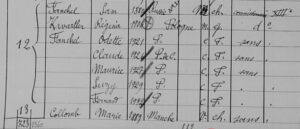

The five children, Claude, Maurice, Fernand, Suzy and Roland, who were deported on Convoy 48, February 13, 1943

The following extract was taken from the 1978 edition of Serge Klarsfeld’s Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France (Memorial to the Jews deported from France). The lists of names of people deported on the convoys were updated by Jean-Pierre Stroweis.

On February 6, the head of the Gestapo’s anti-Jewish department, Röthke, sent a telex to Berlin and to the Sipo-SD in Metz [XXVc-203 and XXVc-204] stating that a third convoy was leaving on February 11, departing at the same time (10:15 a.m.) and carrying the same number of Jews. This convoy was to deport French Jews imprisoned for having broken the law (see convoy notices 46 and 47). Then on February 13, Röthke sent his customary telex to Eichmann and to the Auschwitz camp, saying that at 10:10 a.m. that morning, a convoy of 1000 Jews had left the Bourget/Drancy station for Auschwitz, with lieutenant Nowak in charge of the escort. A note from Röthke dated February 16, [XXVc-207] stated that German forces had to be called in to dispatch the convoy but that, despite their initial hesitation, the French police eventually cooperated as the train departed. The convoy was made up of 466 men, 519 women, and 15 people of unknown gender. There were 150 children under 18 and nearly 300 under 21. This list is in very poor condition; holes made by the ring binder have damaged some of the names, which had to be painstakingly pieced back together. This convoy was made up entirely of French Jews. In fact, the title of the list is “list of a thousand French people.” The deportees had all been living in the Paris area. The list is made up of three smaller lists:

- Drancy – staircase 2: 388 names. Numerous families are among them: Rebecca and Isaac Alvo and their four children, Juliette, 18, Victoria, 17, Jacques, 11, and Rachel, 7. Mendel and Mindla Arm, aged 59 and 51, and their seven children, Hinda, 19, and Berthe, 15. Marcel, 13, 10-year-old twins Charles and Jeanine, Paulette, 7, and Daniel, 5; Haim and Hélène Leiba, aged 50 and 59, and their five children, Adèle, 23, Marcel, 21, Paulette, 19, Jacqueline, 17, and André, 15; Joseph and Esther Mantel, aged 37 and 36, and their four children, Salvator, 14, Renée, 10, Rosette, 9, and Jacqueline, 1; the 5 Fanchel children, deported without their parents; Claude, 17; Maurice, 16; Suzy, 13; Fernand, 11 and Raymonde, who was only six months old; Herman and Filica Avram, aged 35, and their son Christian, aged 1; Chana Esztein, 38, and her two sons, Abraham, 7, and Charles, 5; Lydia Jussim, 4; Jean and Serge Senders, both 6; Regina and Edith Wetzstein, 10 and 3; Ginette and Sylvain Ziemand, aged 7 and 5.

- Drancy – staircase 1: 340 names. Among them, Pierre Grumbach, 11; Pierre Gumpel, 10; Cécile Landau, 10, and her sister Fanny, 7; Alice Lévy, 10; Suzanne Lévy, 2; Léa and Rachel Zawidowicz, aged 13 and 12.

- Drancy – staircase 3: 263 names. Among the children, Berthe Alexandre, 3; Philippe Nozek, 10; Léon and Esther Szejmann, 6 and 10; Szmul Weberspiel, 2; Roland Fanchel 5, whose brothers and sisters are on the list for staircase 2; Claude Attali, 9; Jean and Claude Silberschmidt, 4 and 2; Pauline, Raymonde and Jeanine Yakir, aged 14, 13 and 11.

This convoy arrived in Auschwitz on February 15. 144 men were selected to work in the camp and were assigned serial numbers 102350 to 102492, as were 167 women, with serial numbers 35357 to 35523. Everyone else was gassed immediately. In 1945, there were only 12 survivors, one of whom was a woman.

Claude Fanchel, April 1, 1925 – February 18, 1943

Claude Fanchel was born on April 1, 1925 in Berck, in the Pas de Calais department of France. We were unable to find a record of her birth in the Berck municipal archives. She was arrested on February 2, 1943, interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 48 on February 13, 1943, together with Maurice, Suzy, Fernand and Roland. She was later declared to have died on February 18.

On December 24, 2013, Claude was officially granted the status of “Died during deportation” having been deported on Convoy N°48 at the age of 17. This was published in the French Official Gazette on February 19, 2014.

Source: French Official Gazette.

Maurice Fanchel, January 13, 1927 – February 18, 1943

Maurice Fanchel was born on January 13, 1927 in the 11th district of Paris. He was arrested on February 2, 1943, interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on February 13, 1943 on Convoy 48, together with avec Claude, Suzy, Fernand and Roland.

On December 24, 2013, Maurice was officially granted the status of “Died during deportation” having been deported on Convoy N°48 at the age of 16. This was published in the French Official Gazette on February 19, 2014.

Source: Paris city archives

Source: French Official Gazette

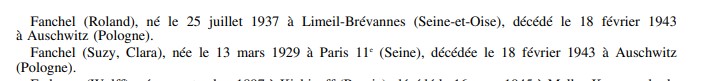

Suzy Clara Fanchel, March 13, 1929 – February 18,1943

Suzy Fanchel was born on March 13, 1929 in the 11th district of Paris. She was arrested on February 2, 1943, interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on February 13, 1943 on Convoy 48, together with Claude, Roland, Maurice et Fernand.

On May 13, 2014, Suzy was officially granted the status of “Died during deportation” having been deported on Convoy N°48 at the age of 14. This was published in the French Official Gazette on July 11, 2014.

Source: French Official Gazette

Fernand Fanchel, February 18, 1931 – February 18, 1943

Fernand Fanchel was born on February 18, 1931 in the 11th district of Paris. He was arrested February 2, 1943, interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on February 13, 1943 on Convoy 48, together with Claude, Suzy, Maurice and Roland.

Source: Paris city archives

On May 13, 2014, Fernand was officially granted the status of “Died during deportation” having been deported on Convoy N°48 at the age of 12. This was published in the French Official Gazette on July 11, 2014.

Source: French Official Gazette

Roland Fanchel July 25, 1937 – February 18, 1943

Roland Fanchel was born on July 25, 1937 in Limeil-Brévannes, in the Val-de-Marne department of France. He was arrested February 2,1943, interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on February 13, 1943 on Convoy 48. During his time in Drancy, this little boy of just 5 years old was separated from his brothers and sisters.

Source: Shoah Memorial archives

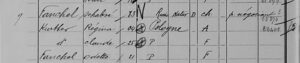

Lina’s comment:

Record from the Shoah Memorial.

The record is an extract from the original deportation convoy list.

It provides us with a list of names of people who were deported on Convoy 48, which left Drancy on February 13, 1943, bound for Auschwitz. The record includes the following information: first and last names, dates of birth, addresses, and places of residence. There were people of all ages, children and adults, women and men, from all over France. The list was type-written. On this image, there is the name of a member of the family that we are researching: Roland Fanchel. His birth date is listed as July 1, 1937.

His address was 43, rue d’Angoulême in Paris. From this record, I discovered that other people from Paris were deported along with Roland. The date of birth listed is incorrect, as we know he was born on July 25, 1937, and was only five years old when he was deported. His name is inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, on slab number 13, column number 5, row number 1.

On May 13, 2014, Roland was officially granted the status of “Died during deportation” having been deported on Convoy N°48 at the age of 5. This was published in the French Official Gazette on July 11, 2014.

Source: French Official Gazette

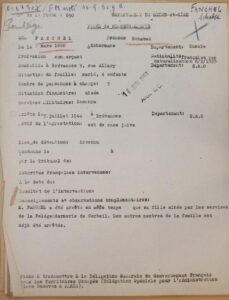

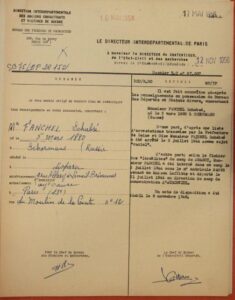

Schabsé Fanchel – arrest and deportation

We know little about what happened to Schabsé, Berthe, and Raymonde, the three remaining family members, between February 1943 and July 1944. Raymonde miraculously escaped being deported, as the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews) intervened on her behalf and took her in. However, Schabsé and Berthe were arrested on July 3, 1944.

Agata’s comment:

We know that S. Fanchel was arrested on July 3, 1944, as his name is on a list kept by the Prefecture of the Seine et Oise department of France ( Convoy 77 archives).

Schabsé was arrested together with Berthe at their home on July 3, 1944, on the grounds their “race”. He was detained in Maisons-Laffitte, in the Yvelines department of France, before being transferred to Drancy. Nathan and Regina Potzeha, whose biographies we wrote previously, were with him.

Madeleine’s comment:

This record is dated October 14, 1957, and lists S. Fanchel’s civil status: it is a check sheet that details his arrests, first in Maisons-Laffitte and then in Drancy. (Shoah Memorial archives)

Tasnim’s comment:

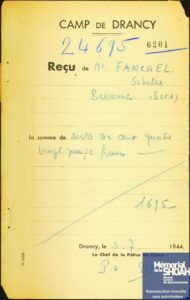

This record comes from Drancy camp. It is about Schabsé Fanchel, and tells us that he was arrested on July 3. It teaches us about the historical context and helps us to remember the victims.

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

Mohammed’s comment:

According to the Drancy search log, Schabsé had 1695 confiscated from him when he arrived in the camp. His serial number was 24695.

Anaëlle Riou, in her paper Une micro-histoire de la Shoah en France. La déportation des Juifs du convoi 77 (A micro-history of the Holocaust in France. The deportation of Jews on Convoy 77), published by Caen University in 2019, says that 60 of the people who were deported on Convoy 77 were arrested in the Seine-et-Oise department, 56 of them in July 1944. “The persecution of Jews intensified as the Liberation drew nearer, and the Germans had no qualms in arresting people all over France, regardless of their age or nationality, with no regard for the French authorities.”

Only four people, including Schabsé, were sent to Maisons-Laffitte before being taken to Drancy, including the three from Brévannes.

By that time, Schabsé’s wife and other children had already been arrested. The Feldgendarmerie (military police) from Corbeil arrested him on the grounds that he was “of the Jewish race” or ”Israelite,” according to a list issued by the Seine-et-Oise prefecture. His financial circumstances were described as “comfortable.”

On July 31, 1944, 1321 people were deported on Convoy 77, including many children that Aloïs Brunner had rounded up in UGIF homes, and Ida Grinspan’s father.

This passage, quoted by Anaëlle Riou, describes the circumstances surrounding the convoy’s departure:

July 31, 1944, Bobigny station. When convoy’s departure day drew near, the internees were told the evening before. “Everything was done to ensure that there were no delays with the buses taking them to the station or as they boarded the cattle cars. This was followed by a terrifying ritual in which the internees summoned for departure were locked in an area surrounded by barbed wire, where the men were shaved and searched and the women were searched and had all their jewelry confiscated. They then spent the night in storage rooms. Early the next morning, SS guards wielding truncheons herded the internees onto buses bound for Bobigny station. The instructions for the other internees in the camp were very clear: “Following particularly strict instructions given to me by SS Hauptsturmführer Brunner, it is strictly forbidden to open the metal window shutters tomorrow from 6 a.m. until the last bus has left. No one is to stand by the windows. The penalties for disobeying these orders will be very severe.”

In Convoy 77’s case, the first bus left at 7:10 a.m.: “The internees will go down into the courtyard at 6:30 tomorrow morning. The first group must be ready to leave at 7:00 a.m.. The first bus will leave at 7:10 a.m. The staff will carry out the roll call.”

Arrival at the camp: We know for a fact that the convoy arrived in the middle of the night, probably during the night of August 3 to 4, 1944, at around 3 a.m. It stopped inside the Birkenau camp. Since May 1944, deportees had no longer been unloaded on the Judenrampe. “It was pitch black; spotlights lit up the route. The train stopped inside the camp. There was no station.” The Jews disembarked and were selected either to go to the gas chambers or for forced labor, but neither group knew at that point what the camp doctor in charge of sorting the deportees had in store for them.

In total, 890 of the 1,294 people who were deported on Convoy 77 were gassed on arrival, including exactly 425 women and 465 men. They were aged between 15 days and 88 years old.

Schabsé died on August 3 or 4, 1944, in Auschwitz, Poland. There are no records of the short time he spent in Auschwitz. He just disappeared without a trace.

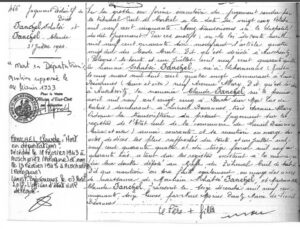

Hanaé’s comment:

Shoah Memorial record.

There is a list of people deported on the various convoys. We can see that Schabsé was deported on Convoy 77.

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

Adam’s comment

The record I have (from the Convoy 77 archives) is about Schabsé Fanchel’s death in Poland

Source: Limeil-Brévannes town hall archives

Maïssane’s comment:

I worked on S. Fanchel’s death certificate (Limeil-Brévannes town hall archives), which contains some information about his life. Born in Russia in 1880, he lived in Limeil-Brévannes until he was deported to Auschwitz, where he died.

Claude Fanchel was one of his daughters. She was born on April 1, 1925 in Berck-sur-Mer in the Pas-de-Calais department. She then lived at 9, avenue Allary in Limeil-Brévannes. We do not know the exact cause of her death.

The survivors: Berthe, the oldest daughter, and Raymonde, the youngest.

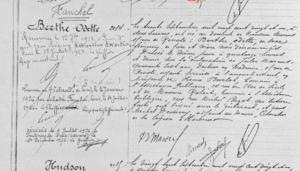

Berthe Odette Fanchel

Photo on the headstone at Bagneux cemetery in Paris. Source: Geneanet

Berthe was born on October 30, 1921, in the 4th district of Paris. She died on July 4, 1976 in Fontenay-lès-Briis, in the Essonne department of France. Her mother, Régina, officially recognized Berthe as her daughter in 1922, and her father did the same on January 10, 1926.

Source: Paris city archives.

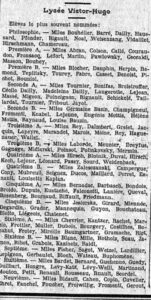

She was a talented student, as reported in the French newspaper Le Temps: in 1931, she was one of the most frequently named students from Victor Hugo High School (when she was in 9th grade).

Source: Gallica

Berthe was arrested at the same time as her father, but she was not deported. We do not know why this was the case.

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

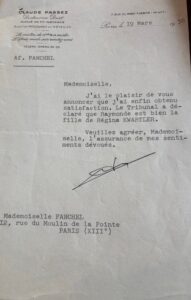

On February 5, 1953, the French government declared her youngest sister Raymonde, who also survived the war, to be a ward of the state. Berthe Odette Fanchel was appointed her legal guardian.

In the late 1950s, she was living at 12, rue du Moulin de la Pointe in the 13th district of Paris. A man called Joseph Birolo, who we shall come back to later in this biography, had bought the property.

Berthe is buried in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris alongside Clara Fanchel and Raymonde, (their cousin, Jacques Tokar, from Schbabsé’s mother’s side of the family, and his wife, Eliane are also buried there).

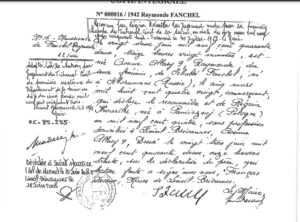

Raymonde Fanchel

Photo on the headstone at Bagneux cemetery in Paris. Source: Geneanet

Jo-Yie’s comment:

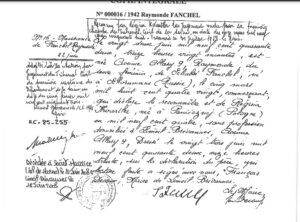

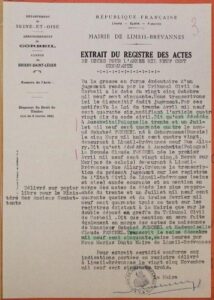

The record I worked on is a copy of Raymonde Fanchel’s birth certificate, from the town hall in Limeil-Brévannes. Raymonde was a girl, and the youngest of Schabsé Fanchel’s seven children. She was born at 1:20 p.m. on June 22, 1942, at 9 Avenue Allary. Her father, who was a merchant born on March 5, 1880, in a town in Russia, had officially recognized Ramonde as his daughter. Her birth certificate was issued at 11:30 a.m. on June 23, 1942, based on her father’s declaration. He read the certificate and signed it alongside the mayor of Limeil-Brévannes. Raymonde Fanchel died at the age of 66 on June 14, 2008 in Saint-Maurice, in the Val-de-Marne department of France. From this record I learned that a French birth certificate includes the exact time, date and place of the birth and the child’s parents’ details. In Raymonde’s case, we can see all the information about her and her parents, such as Schabsé’s date and place of birth, and his occupation at the time.

Diego’s comment:

I also studied a copy of Raymonde birth certificate, from the town hall in Limeil-Brévannes. She was born on June 22, 1942, in Brévannes. Her father came from Russia and her mother from Poland. They lived in Brévannes. She died on February 14, 2008, in Saint-Maurice.

Raymonde Fanchel’s birth certificate. Source: Limeil-Brévannes town hall

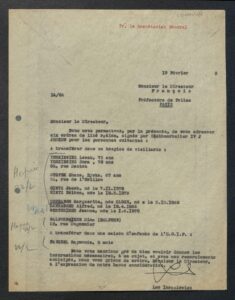

Raymonde Fanchel was born on June 22, 1942 in Limeil-Brévannes, in the Val-de-Marne department of France. She was Régina Kwartler and Schabsé Fanchel’s youngest child, and Berthe Odette, Claude, Maurice, Suzy, Fernand and Roland’s youngest sister. Raymonde was arrested on February 2, 1943 together with her mother, Claude, Maurice, Suzy, Fernand and Roland. They were all interned in Drancy the following day, February 3. On February 22, eight-month-old Raymonde was transferred to a UGIF children’s home, as documented in Léo Israelowicz’s letter dated February 19, to Mr. François, the Director of Administrative Affairs for the Paris General Police, about requests for the release of prisoners interned at Drancy (CDXXIV-44 p.120). She thus became what was known as a “blocked child”. As a result, Raymonde [3] was not actually deported, even though her name is on the Convoy 48 deportation list. This is because the list was drawn up in advance, when she was still scheduled to be deported.

Léo Israelowicz’s letter of February 19,1943. Source: Shoah Memorial

Madeleine, Hana and Irem’s comment:

This record is dated February 19, 1943. It is a letter from Léo Israelowicz to the Director of Police Headquarters. It refers to people who had been released under a “liberation order”. It lists the individuals in question, along with their ages and addresses. It tells us that Raymonde Fanchel was released and transferred to a children’s home when she was 8 months old.

Lina, Jaya and Maïssane’s comment:

This document is a letter from the Paris Police Headquarters to the manager of the Drancy camp. It is dated February 19, 1943. It contains a list of elderly people and one child, eight-month-old Raymonde, who were to be transferred. It thus reveals that Raymonde Franchel was not deported.

We also have a page from a register, kept by a priest, Father Devaux, of children taken into care during the war: it includes first and last names, dates of birth, the child’s place of residence, names of guardians, and the name of the person taking care of the child. This was sent to us by Héléna Rigaud, Archivist at the Sisters of Notre-Dame de Sion[4]. Raymonde must have been moved out of a UGIF home and placed with a family, just before the roundups in the UGIF homes.

A page from the register kept by Father Devaux of children taken into care during the war. Source: Héléna Rigaud, Archivist at the Sisters of Notre-Dame de Sion

Diego and Devan’s comment:

This record tells us that Raymonde’s surname was changed to Colombel. She was kept hidden by a Mr. Birolo in 1944, when she was 2 years old. He received two payments of 900 francs to pay for the board and lodging of Raymonde’s nanny, Ms. Le Louarec.

Joseph Birolo, who was an Italian citizen, acted as guarantor for Raymonde Fanchel (also known as Colombel) when Ms. Le Louarec was taking care of her. By 1946, he and the two surviving Fanchel sisters were living at 72, rue du Château d’Eau, with Raymonde listed as his goddaughter.

Source: 1946 census of Paris

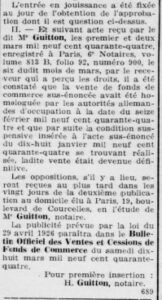

According to the French newspaper La loi , on March 11 and 29, 1944, Mr. Birolo bought a business from Régina. It was based at 12, rue du Moulin de la Pointe in the 13th district of Paris:

Source : Gallica.

Source : Gallica.

Raymonde survived, even though her mother was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 47 on February 11, 1943, followed by her five brothers and sisters on Convoy 48, on February 13, 1943.

Her father, Schabsé, was deported on Convoy 77, which left Drancy on July 31, 1944.

Her eldest sister, Berthe Odette, was not deported either. She became Raymonde’s legal guardian after the war (according to records from her father, Schabsé Fanchel’s file, ref. DAVCC 21 P 448 583 and a questionnaire that she completed, held at the Notre-Dame-de-Sion convent, ref. DI (100).

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C), French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

Jo-Yie and Nola’s comment:

The document we studied is a contains information about the Fanchel family. The parents and five of their children died. The father was a salesman and lived on Rue d’Angoulême in Paris. His wife, Regina, was born in Poland. The only members of the Fanchel family who survived were Berthe and Raymonde. The letter was addressed to Berthe. The father of the family was arrested in July 1944 and the mother in February 1943, along with their five children. They were all deported. This document was drawn up after the war in order to determine what happened to them.

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961, French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Raymonde was made a ward of the State in 1953, in the Seine department of France. At the time, she was living with Berthe, who became her legal guardian. Since Régina and Schabsé were divorced, Berthe had to prove that her sister was her parents’ heir. A note on Raymonde’s birth certificate states that the Seine court ruled that she was Regina’s daughter on March 11, 1958.

The letter addressed to Berthe. Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission

Raymonde’s birth certificate, with notes added. Source: Limeil-Brévannes municipal archives

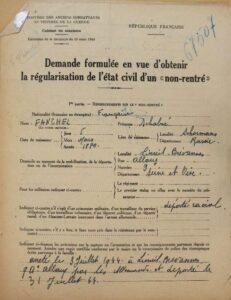

Berthe had to deal with a great deal of paperwork and make numerous requests in relation to her family. The first step was to apply for her father to be granted the status of non-returned person. She submitted the request in Villeneuve Saint-Georges on October 15, 1949[5].

Anaëlle Riou, in her paper “A micro-history of the Holocaust in France. The deportation of Jews on Convoy 77”, wrote:

“The reconstruction of the families or survivors’ life stories often involved applying for the status of “Political Deportee” or “Deported Resistance Fighter.” This brought surviving family members not only official recognition from the State, but also financial compensation, of a sortIt was especially difficult to prove that a person had been arrested because they were a member of the Resistance. As a result, 23 deportees were not awarded the title of Deported Resistance fighter, but were instead granted Political Deportee status. A total of 684 deportees were recognized as Political Deportees.”

Nola’s comment:

This record is dated March 16. It is a request to rectify the civil status of a “non-returned person”. It appears to involve administrative or legal questions relating to the identity or status of a person who was not previously listed in the civil registers. What I learned from this is that this type of document is often essential when it comes to proving legal rights or accessing support from the authorities. It also demonstrates how important it is for people to have their civil status rectified, as this can affect many aspects of a person’s life. (Convoy 77 archives).

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Amayas’ comment:

The record I studied is undated ( i.e. there is no date of issue on it). It is a request to have the civil status of a “non-returned person” rectified. It contains information about Schabsé Fanchel, including his date and place of birth, date of death and address. What I learned from the record: Schabsé Fanchel, who was born on March 5, 1880 and died in 1944, lived at 9, rue Allary in Limeil-Brévannes. He was arrested by the Germans on July 3, 1944 in Limeil-Brévannes and deported on July 31, 1944. He had traveled a lot and came to live in our town with his wife and seven children (Convoy 77 archives).

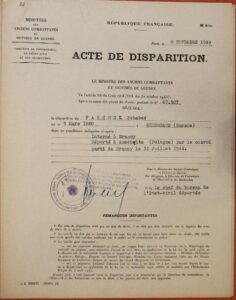

Berthe then obtained a missing persons certificate:

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Lastly, Berthe applied for her father, a First World War veteran, to be granted the status of “Died for France”. However, her request was turned down as she could not prove that her father had been a member of the Resistance during the Second World War.

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

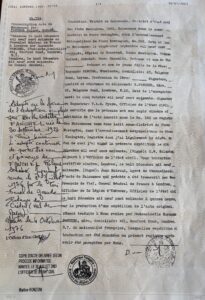

Some of the records are kept in a green folder called the Fichier de Brinon (de Brinon File), which is named after Fernand de Brinon, who was the Vichy government’s delegate general.

It contains, among other things, Schabsé’s missing persons certificate, issued by the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs. In 1949, Berthe applied to have his civil status rectified. The mayor of Limeil, Marius Dantz, recorded both Schabsé’s and Claude’s deaths in 1950.

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

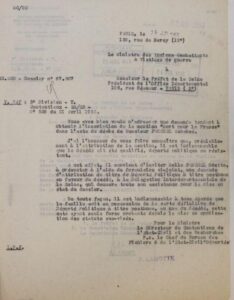

In 1956, the case file on what happened to him during the war was still being dealt with:

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

Ismaïla et Ismaël’s comment:

This record dates from May 17, 1956: it was issued by the Interdepartmental Directorate for Veterans and Victims of War, and is addressed to the Litigation Office. It relates to Schabsé’s deportation to Auschwitz, when he was arrested on grounds of his “race”, detained at Drancy and then deported. It states that a missing persons certificate was issued on November 8, 1949.

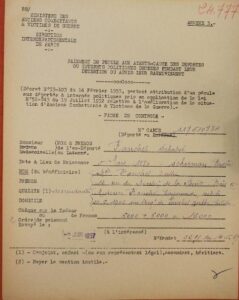

In 1957, Berthe and Raymonde received a payment of 12,000 francs, the statutory compensation payment calculated according to the number of months during which the person was interned. The French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) conversion tool [6] estimates that this would have been the equivalent of 280 euros in 2023.

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

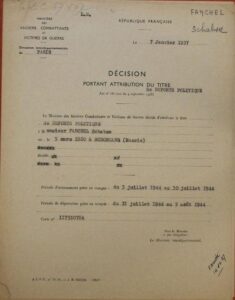

At the same time, in 1957, Schabsé was granted “Political Deportee” status, but still not that of “Died for France”. His deportee card number was 117510784.

It was not until July 27, 1989 that he was finally declared to have “Died during Deportation”. This was published in the French Official Gazette on October 18, 1989.

Source: FANCHEL_Schabse_21_P_448_583_9961 (C) French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

Naïm and Mohamed’s comment:

The record dates from January 7, 1957. It relates to a decision by the French Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War to grant the status of political deportee. It is an official document awarding the status of political deportee to Mr. Fanchel, who was born on March 5, 1880 in Russia. Issued by the Interdepartmental directorate in Paris, it states that two periods of internment and deportation were taken into account: from July 3, 1944 to July 30, 1944, and from July 31, 1944 to August 5, 1944. From it, we learned that Mr. Fanchel was granted the title of political deportee. This was an important acknowledgement for people who had been imprisoned or deported for political reasons. Schabsé Fanchel was one of them. (Convoy 77 archives).

Ismaïla’s comment:

Even though I did not quite manage to decipher the record in its entirety, I tried my best and extracted the following information from it: it was issued by the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and is dated June 12, 1953. It refers to the death of Schabsé Fanchel, who died in Poland, and whose family requested that he be granted political deportee status. (Convoy 77 archives).

Amayas and Adam’s comment:

The record is dated January 7, 1957, and is about Schabsé Fanchel. It tells us that he was granted the title of Political Deportee. He was interned from July 3, 1944 to July 30, 1944. The record was issued by the Interdepartmental directorate in Paris. His deportee number was 117510784. The letter is addressed to his daughter, Berthe Odette.

Kylian and Fodye’s comment:

The record we studied is a letter from the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and is addressed to Berthe, who was living at 12, rue du moulin de la Pointe in the 13th district of Paris. The letter is dated December 9, 1957. It refers to her request for the status of Political Deportee.

We know very little about the sisters’ lives after the war, but Berthe did a lot to support her younger sister. She worked as a secretary in Créteil, on the outskirts of Paris. She died from cancer in 1976.

When Raymonde died, in 2008, no one claimed the money in her bank account. It was therefore invested in the French state Caisse des Dépôts (Deposits and Consignments Fund).

Two names came to light during our research on the French genealogy website, Geneanet: a Mr. Roland Schabsé FANCHEL, born in London on September 29, 1960 and died on Wednesday, May 1, 2024 in the Draveil hospital at the age of 63. And then we found a Ms. Suzie Nadia FANCHEL, born on Sunday August 20,1967 in Villeneuve Saint-Georges, in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, and died at the age of 33 on Tuesday, July 3, 2001 in hospital at Lons le Saunier, in the Jura department of France. She lived in Cormoz, in the Ain worked on the markets. According to their death certificates, these were Raymonde’s children. Another interesting detail is that Roland Schabsé, who lived in Morangis, in the Essonne department of France, had also been adopted by Berthe Odette, his aunt.

When I wrote to the registry office at Limeil Brévannes town hall to ask for further information about where they lived, the deputy mayor, Mr. Daniel Gasnier, who dealt with my letter, remembered that around ten years ago, some cousins of the Fanchels had contacted him to find out what had happened to the house on avenue Allary, but that their letter was nowhere be found.

In late December, 2024, when I obtained copies of Roland Schabsé and Suzie Nadia’s death certificates, another question came to mind: if Raymonde had children, why had her estate never been settled? And why would her children have been buried so far away from her?

As for Roland, he had made a Will: I therefore wrote to the notary who dealt with his estate, but she replied to say that she was obliged to respect client confidentiality.

And then, just a few days later, on January 8, I got a phone call from a man who told me he was Roland’s adopted brother…

Jean-Noël Journo introduced himself to me as follows: his parents had worked with Berthe Odette, a secretary, in Créteil in the 1960s, and they had become friends. Berthe had officially adopted Roland, after having previously adopted Raymonde. Raymonde always lived on the edge of mainstream society, despite her sister’s efforts to help her claim what she was entitled to.

While studying in England in 1960, Raymonde had given birth to a son, Roland Schabsé, on September 29.

Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission.

During her stay in London in 1960, Raymonde lived at 43 Belgrave Road in Leyton and at 461 Romford Road in Manor Park. She then returned to France and left her son with Berthe Odette, as documented in a ruling issued by the Bobigny court in 1971 and an adoption decree issued by the court in July 1976, presumably following Berthe’s death on July 4, 1976.

Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission.

Berthe Odette employed a nanny to take care of Roland between September 1965 and 1970. The nanny also gave evidence in support of Berthe Odette during the adoption process.

Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission.

Raymonde also had a daughter, in 1967, in Villeneuve Saint-Georges. She was called Suzie Clara, and was probably taken into care or placed with a family.

Berthe and Raymonde stayed in touch, despite Raymonde’s problems.

At some point, Berthe moved from Limeil Brévannes to 2, rue Jean Cavaillès in Villecresnes, south east of Paris.

In 1974, Berthe, aware that she was seriously unwell, asked the Journo family, who were work colleagues and close friends, to take care of Roland. They already had 8 children of their own.

The youngest, Jean-Noël, was a year younger than Roland, and as they grew up, they became very close.

When Berthe Odette died in 1976, Raymonde vanished from Roland’s life, although she kept in touch with the Journo family sporadically.

When Roland fell seriously ill in May 2023, he left his estate to Jean-Noël.

Jean-Noël on the left and Roland Schabsé on the right. Source: Mr. Journo’s personal collection, reproduced with his kind permission.

When Roland died, Jean-Noël contacted the Bagneux cemetery, but staff there were unable to locate the Fanchel family vault. Roland is therefore buried with his foster parents, the Journos, in the Pantin cemetery in Paris.

It turned out that Berthe had sold the house on avenue Allary.

Their notary, after I spoke with Jean Noël, called me with her version of the story.

During this very moving conversation, it became clear that Roland had never known his sister Suzie, 7 years his junior, who died when she was young.

Roland, therefore, had never been aware of the whole story.

The notary explained that it was a once-in-a-lifetime situation.

Another thing was that it appears that Berthe was either unable, or did not know how, to make a claim for the assets taken from her family during the war.

The search for the last remaining piece of the puzzle began.

Jean-Noël and I, with the help of the notary, have filed a claim with the CIVS (the French Commission for the return of property and reparations for victims of anti-Semitic spoliation) for compensation for property confiscated during the war.

Sadly, my father would never witness the end of this odyssey, which began in 2019.

Source: Geneanet.

This investigation was carried out by the amazing students of class 4eC at the Daniel Féry secondary school in Limeil-Brévannes, led by Mr. Habert, the school principal, a keen amateur historian.

The students are: Irem, Lina, Maïssane, Tasnim, Edison, Fodye, Agata, Devan, Nola, Salimata, Mohamed, Inassio, Ismael, Diego, Abigaelle, Madeleine, Ismaïla, Gabriel, Amayas, Lana, Jo-Yie, Jaya, Kyilian, Naïm, Hanae, Adam and Malak.

The team at the Daniel Féry school is much more than just a gathering in the teachers’ common room, as is often the case eslewhere, and this is borne out by the work of these 13-year-old students.

Acknowledgments

I would like to warmly thank Claire Podetti and Georges Mayer from Convoy 77 for their help, advice and kindness, as well as for visiting our school, all of which contributed to the success of this project.

Our thanks also go to the municipal registry offices that kindly answered our questions, to the archives services we contacted and, of course, to the Shoah Memorial and the rest of the Convoy 77 team.

Lastly, thank you to the notary, Ms. Lecaillon, for the trust she showed in me, and to Jean-Noël Journo, who I shall be seeing again, for enabling me to conclude all these years of research.

Limeil-Brévannes, 27 January 2025

Notes and references

[1] Fonds de l’état-major de l’Armée (1872 – 1940) – GR 7N Archives SHAT 7 N 160 160 Idem: combattants étrangers; travailleurs étrangers en France (foreign fighters; foreign workers in France); 6 N 97; 7 N 1287 Engagements dans la Légion étrangère, correspondance (1914-1924) (Foreign Legion enlistments, correspondence (1914-1924))

[2] This statement is not included in the book

[3] Correspondence from September 24, 1942 to June 25, 1943 between Léo Israelowicz of the UGIF, northern zone, and Mr. J. François, director of administrative affairs with the General Police in Paris, about requests for liberation of internees detained in Drancy CDXXIV-44 P 120 Title: Fonds de l’Union générale des Israélites de France (UGIF) – instrument de recherche général / Author: Israelowicz, Léo Period: September 24, 1942 – June 25, 1943; Physical description: 157 documents Language: French Origin: Israelowicz, Léo Summary: Liberation orders, which made reference to Leo Israelowicz’s letters, were signed by Röthke, Ahnert and Heinrichsohn Terms of use: Obligatory acknowledgement: Shoah Memorial. No use without prior authorization Place: FRANCE

[4] The archives of the Fathers of Sion: The files referred to by the Shoah Memorial are kept by the Fathers, but there is no file relating to Raymonde Fanchel (questionnaire/response).

[5] Collection of documents, dated from the end of the Second World War and the post-war period, comprising questionnaires, photographs and letters, completed and addressed to the Order of Notre-Dame-de-Sion by relatives of deportees in order to obtain information about them: DI(1-264) DI(100) Title: Fonds Notre-Dame de Sion Author: Schwob, Lise Ameau, Norbert, 3 Meyer, Michel, 3 Period: November 13, 1944 – February 18, 1947; Physical description: 250 documents Particulars: Inscription, Signature, Photographs Language: French Summary: This collection of documents comprises mainly questionnaires filled in with information provided by relatives of deportees, including surnames, first names, dates and places of birth, dates of arrest, dates of deportation, occupations and residences of deportees, the names and ages of their children, and the names and addresses of any remaining persons to whom the information should be sent. Photographs of missing persons often accompany the questionnaires, as well as, more rarely, letters written by deportees’ relatives. A genealogy of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond and Antoinette Berr, a biography of Mr. Raymond Berr, a list of his military titles and decorations, as well as his scientific titles and publications, a note from the Kuhlmann company on the arrest of the Berr family, a letter from Norbert Ameau, secretary to Colonel Rebattet, dated April 9, 1945, addressed to Mr. Jean Cerf concerning the search for his brother, Mr. Paul Cerf, who had been deported; three “request for search for a deportee” forms from the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees concerning Messrs. Hersz Dreksler and Lévy Goldbroit; five “confirmation of death” forms dated February 18, 1947 concerning the Gattegno family (Jean, Letitia and their children, André and Eliane) and Mr. Armand Lambert, a postcard of the Château d’Habère-Lullin, which was set alight by the Germans on December 25, 1943, a letter dated August 3, 1944 from the French Minister of Justice and President of the Council of State to the French Ambassador, Delegate General of the Government for the Occupied Territories requesting information on Mr. Pierre Isidore Lévy, Senior Counsel at the Council of State and deportee, and a form from the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees dated October 20, 1945 certifying that their services had issued a certificate stating that Mr. Jankel Lewin had been deported to Germany on July 17, 1942. The files are in alphabetical order.

[6] Adjusted for inflation.

Français

Français Polski

Polski