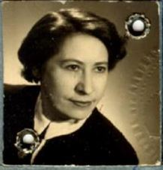

Rose LENDOWER (1907-1982)

© Family archives, Muriel Lendower

The 12th grade History-Geography, Geopolitics and Political Science students from the Marcel Pagnol high school in Marseille, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of France, carried out a historical investigation in order to write this biography of Rose Lendower. They based their work on historical records. After cross-checking the sources, they were left with a number of questions: by creating a network of memorial sites and meeting with witnesses, they were able to finalize the biography in 2025.

ROSE’S LIFE BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Rose Mizreh was born in Batzi[1], then in Romania but now in Moldavia, on December 18, 1907[2]. She moved to France with her parents, Aba and Pesca, née Cleiman, in 1920[3]. Her father was a furrier, as was her brother, Maurice. She was the third of ten children. Her youngest siblings, twins Jacques and Madeleine, were born in Milan, Italy, in February 1921. Might the family have lived there for a time? Whatever the case, they were back in Paris when Madeleine died at the age of 3, on November 16, 1924.

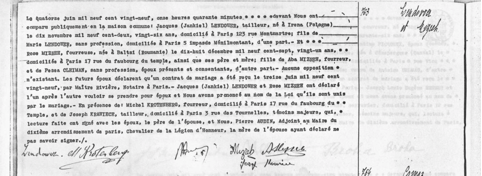

Rose married Jankiel, also known as Jacques, Lendower, who was born on December 10, 1905 or 1902 in Radzymin / Irena, Poland, on June 14, 1929, at the town hall in the 10th district of Paris. He was a Polish citizen at the time[4]. A marriage contract had been drawn up the day before the wedding. One of their witnesses was Michel Krotenberg, Rose’s brother-in-law.

At the time of the wedding, Jacques was working as a tailor and living at 123, rue Montmartre. His mother also lived in Paris. Rose was working in the fur trade[5].

@ Paris city archives. 10th district of Paris marriage register, June 14, 1929

The couple went on to have one son[6], Joseph, known as Georges, who was born on December 14, 1930 in the 12th district of Paris. The family lived at 50, rue du Faubourg du Temple, in the 11th district, a neighborhood well known for the manufacture of fabrics, clothing and hats, which was home to a large number of Jewish workers and traders.

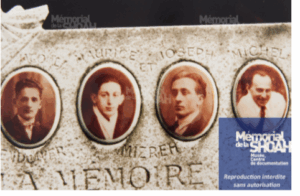

Jankiel Lendower, Rose’s husband: photo on a monument dedicated to him, her two brothers and her brother-in-law, who were murdered in Auschwitz (source: Shoah Memorial, Paris)

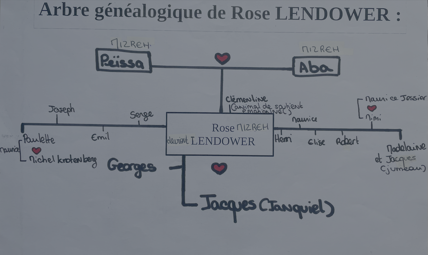

Rose Lendower’s family tree, made by Chahinez, Lizy, Kélia, Tom and Yanis.

On September 3, 1939, England and France declared war on Nazi Germany.

When the Germans began to invade France in May and June, 1940, the French army was unable to hold them back. As a result, Philippe Pétain, the new leader of the French government, asked for an armistice, which was signed on June 22.

Just before that, on June 18, General Charles De Gaulle, the Under-Secretary of State for War in Paul Reynaud’s short-lived government, who had left for London with some members of the armed forces who refused to surrender, had appealed to the French people to resist.

We wondered if that what prompted Rose to join the resistance movement and oppose the Nazi occupiers.

Soon after the Vichy government (named after the town in the Allier department, to which it had fled) agreed that France be divided into two zones and decided to collaborate with the Third Reich, the Jews in France were branded as “undesirable”. Many French people accepted or even supported the Nazi policy of discrimination against the Jews. On September 27, 1940, the Jews in the occupied zone were obliged to register themselves with the French police. They were also forbidden to work in various professions, and banned from public places such as parks, squares and subway trains (except for the last car). That same year, 1940, the first arrests of Jews took place. Then, on October 3 and 4, prefects were given the right to intern “foreigners of the Jewish race” in “special camps”. They were often then deported to camps in Poland.

Rose experienced these arbitrary arrests at first hand. Her husband Jacques was arrested, along with 3709 other Jews, and taken to the Japy gymnasium in Paris on May 14, 1941 during the “green-ticket roundup”. He was transferred to the Pithiviers camp, in the Loiret department of France, and deported on convoy 4 to Auschwitz-Birkenau on June 25, 1942.

According to her family, Rose became a Resistance fighter soon after that, partly because she was determined to be an independent woman, partly for personal reasons, and also because she felt it was her duty. She thus became involved in the resistance movement very early on.

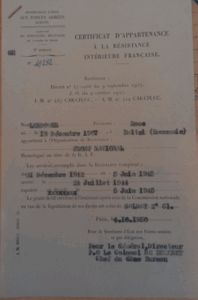

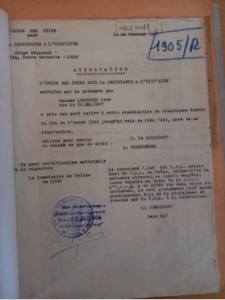

According to French Internal Resistance membership certificate, which was signed after the war by Colonel Belinet[7], Rose joined the Front National de Lutte pour la Libération de la France (National Front for the Liberation of France) in 1942 and remained a member until the day she was arrested. The group had been founded by the French communist party in 1941. She was also involved in the Lyon-based UJRE (Union des Juifs pour la Résistance et l’Entraide, or Jewish Union for Resistance and Mutual Aid), according to an affidavit signed by A. Werkhaiser[8].

The UJRE, as FFI (Forces françaises de l’Intérieur or Free French forces) commander Jean Gay explained, “was the only Jewish group in our department that actively participated in the Resistance and was recognized by the C.D.L/ following the Liberation”.

In 1950, Rose was awarded the rank of “second class private” for her work in the Résistance Intérieur Française, or French Interior Resistance (RIF)[9].

Source: French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, dossier 16 P 421 792

Source: French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, dossier GR 16 P 421 792

Rose’s work in the Resistance included distributing leaflets, collecting clothes and taking care of the children of people who had been deported[10]. She also managed to collect food, at a time when supplies were short, to help feed Jewish children, including some who were being kept hidden.

This was confirmed by the person who wound down the National Front for the Liberation of France network, who also noted that she was arrested “after a distribution of equipment in Lyon”[11].

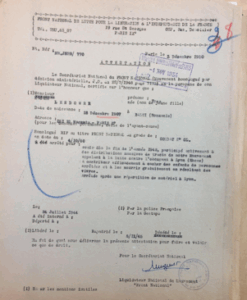

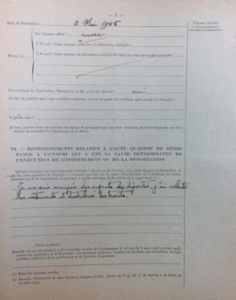

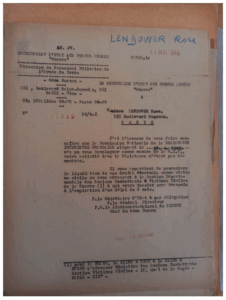

Application for deported resistance fighter status, dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P 561 429.

It was probably soon after her husband’s arrest in May that Rose left Paris for Lyon, in the Rhône department of France. In 1941, she moved in with her sister Pauline (Peila aka Paulette) and her husband Michel Krotenberg. She was still living there in 1944, at 66, grand-rue des Feuillants, and was working at 62, boulevard des Brotteaux in a fur workshop rented by her older brother, Joseph Mizreh[12]. Rose’s son, Georges, was safely hidden away somewhere, probably in the countryside.

Rose carried out her resistance work on the quiet, which was very wise. She used counterfeit identity papers without the yellow star that Jews’ papers were required to have[13] Later on, in her application for official recognition and a pension, Rose named one of her fellow resistance workers as a Mrs. Tipperman[14].

ROSE’S ARREST, ON JULY 4, 1944

Two women, Mrs. Merle and a Mrs. Ravel, witnessed Rose being arrested at her brother’s fur workshop. They testified that the French militia and the Gestapo arrested her on July 4 1944[15]. Her brothers and her brother-in-law, Menachem (known as Michel) Krotenberg, were arrested at the same time.

Rose identified herself as a Jew to the militiamen who came to arrest her. Most Jewish resistance fighters were taken to Drancy and deported on the grounds that they were Jewish, and since no evidence of Rose Lendower’s resistance work appears to have been found by the Nazis, she too was interned and deported as a “Jew”.

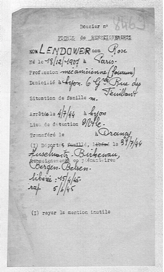

Source: Rhône departmental archives, ref. 3335 W 27 Dossier n° 8469: Liberated and repatriated deportees

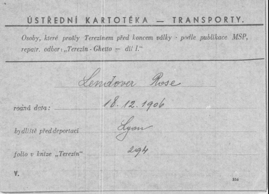

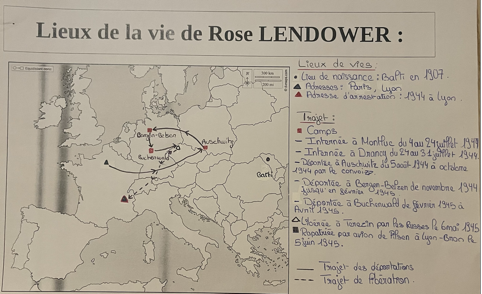

She was held in Fort Montluc jail in Lyon, together with her brothers and brother-in-law, from July 4 to July 22, 1944[16], when a large number of Jewish prisoners were transferred by train to Paris. Rose was then interned in Drancy camp from July 24 to July 31, 1944[17] when she was deported on Convoy 77 to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and extermination center[18].

THE DEPORTATION

After a grueling journey that lasted three days and nights, Rose was selected to go into the camp to carry out forced labor. The number A16656 was tattooed on her forearm[19].. As soon as the convoy arrived in Auschwitz, she was separated from her brothers and brother-in-law, never to see them again.

Rose remained in Auschwitz until the end of October, 1944[20]. The records reveal that she was then transferred to a series of other camps, the first of which was Bergen Belsen, in Germany, where she was held from November 1944 to February 1945[21]. Next, in accordance with an official order dated December 6, 1944, she was one of 500 female prisoners who were transferred from Bergen Belsen to Raguhn, a satellite camp of the larger Buchenwald camp. There, according to a list of political prisoners in the camp dated March 1945, she was assigned the number 67296. Ginette Kolinka was another of the women who, like Rose, was assigned to this very tough Kommando, which was on an air base where weapons components were manufactured. Some other women from Convoy 77, including Marcelle Stark, Carmen Menaches and Marie Broder, shared the same fate.

Rose remained in Raguhn from February 12 to April 10, 1945[22]. Then, when the Kommando was disbanded, she and the other 480 or so women who were still alive were transferred to the Terezin (Theresienstadt) camp-ghetto in Czechoslovakia. Once again, the women had to endure a grueling eight-day journey in cattle cars. She remained there until May 6, 1945[23], when a group of Czech partisans and the Red Army liberated the camp.

AFTER THE WAR

Repatriation

In early June, the women liberated from Terezin began to be repatriated to France.

Map of Rose Lendower’s journey, drawn up by Dewene and Elsa

According to her repatriation card, no. I.020.909, Rose returned to France by air from Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, to Lyon-Bron airport, in the Rhône department of France, on June 5, 1945. Only deportees in an extremely poor state of health were repatriated by plane. She then went back to Paris, where she spent some time recovering in a sanatorium.

Rose’s health badly damaged

A report from the rehabilitation center in Paris[24] reveals that Rose had significant deportation-related health problems: pulmonary tuberculosis, a left-lung pneumothorax, a silent left lung and some sub-clavicular tracts on the right lung. The damage she sustained was certified as “contracted during deportation”. On January 15, 1951, the Chief Medical Officer recommended that she be awarded a temporary pension of 100%. She was then classified as a “Resistance fighter”, and the doctor said that she should be re-examined in three years’ time.

Her request for the status of “Deported Resistance fighter” refused

In order to qualify for a pension for her services in the Resistance, Rose had to put together a claim file. This turned out to be just the beginning of a veritable obstacle course.

In 1947, Rose requested official proof of her Resistance work, in order to apply for the status of Deported Resistance fighter. In February 1947, the UJRE confirmed that she had been active “from the end of 1942 until June 1944, when she was deported”. She submitted her application and the official attestation on March 22, 1949, explaining that the delay was due to her medical condition.

Her application was refused in May 1949.

She appealed against the decision, but to no avail, despite the fact that she had been issued with a certificate attesting to her Resistance work on October 4, 1950. The reason given for this second refusal, in late 1950, was that she had provided an attestation, but no supporting witness statements.

Source: French Defense Historical Service dossier GR 16 P421 792. Refusal to grant the title of “Deported Resistance fighter”, dated May 11, 1949

Despite all her efforts, she was only granted “political deportee” status [25]. She received a political deportee card bearing the number 210110805[26] and a “compensation” payment for political deportees and internees[27].

Rose Lendower’s Political deportee card. Source: Family archives

Naturalized as a French citizen

In 1946, Rose applied to be naturalized as a French citizen and was granted French nationality on March 6, 1948. At the time, she was living at 151, boulevard Magenta in the 10th district of Paris. In September 1954, she moved to 52, rue du Faubourg Poissonnière, also in the 10th district. She eventually regained her health and opened a shop together with her son.

Rose died on December 26, 1982, in a retirement home on rue de Picpus in Paris. Her name is inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris an on a memorial in Lyon.

A family torn apart by the Holocaust

Rose’s two brothers, Maurice (born in 1913) and Joseph (born in 1903), were also deported but never came home, and the same was true of her brother-in-law, Michel. At least three of her brothers were still alive after the war, however: Serge (1910-2002), Robert (1919-2016) and Jacques (1921-1996), who was also a member of the Resistance and fought with the FFI. Rose’s sister Pauline was still trying to find out what happened to her husband Michel in 1969. Their parents were not deported.

Memorial plaque Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris / Serge Klarsfeld collection

OUR MEETING WITH ROSE’S GRANDCHILDREN

We were able to arrange a video meeting with Rose’s grandchildren, Muriel and Olivier. They agreed to answer our questions, for which we are extremely grateful.

Here are their replies:

Muriel, Rose’s granddaughter, managed to gather together some archives ten years ago.

Rose became a Resistance fighter because she wanted to be a free woman, for personal reasons, out of a sense of duty, and because some of her family members had been deported.

She used false identity papers during the war. She eventually recovered her health.

After she returned home from the camps, she opened a ready-to-wear business with Georges.

She never remarried, and lived alone with her son Georges, who was kept hidden during the war and never discussed the deportation with his children.

Rose was very close to her family.

She hid the fact that she had a number, A 16656, tattooed on her right arm: she said it was a bee sting.

Rose did not vote in 1945, even though French women had won the right to vote and be elected in 1944. She was in a sanatorium in Switzerland with lung problems. Most importantly, she was not a French citizen at the time (she was naturalized in 1948). Her dossier from the French Defense Historical Service in Caen shows that she applied for naturalization in 1946.

Rose continued to be politically active after the war, although she was no longer a Communist.

She never spoke very much, but the main thing was she was close to her family and friends.

Rose’s son Georges, Muriel and Olivier’s father, took care of her until she died[28]. Afterwards, they took in her little dog, Clémentine.

Her descendants do not know if they still have family in Moldavia, if they all died or if they survived the Holocaust.

STUDENTS’ COMMENTS ON THE PROJECT

In what way has the project contributed to keeping Rose Lendower’s memory alive?

Why it’s important to work on historical project such as this?

Well done and thank you to the following students for all their hard work: Chahinez, Asna, Elyes, Eva, Guilherme, Tom, Cassandra, Xavier, Gabriel, Alexandre, Kélis, Quentin, Mehdi, Annie, Sarah, Kélia, Sana, Lizy, Alisson, Jessee, Soukeyna, Elsa, Jasmine, Yanis, Rayan and Dewene.

Notes & references

[1] Certificate of French nationality dated September 22, 1950, Rose Lendower, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Dossier n°21 P 561 429.

[2] Online meeting with Rose’s grandchildren on February 4, 2025.

[3] Family Archives

[4] Jankiel Lendower, Shoah Memorial, Paris, https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=jankiel%20lendower&spec_expand=1&start=0

[5] Investigation into Rose’s arrest dated February 7, 1952, Rose Lendower, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, idem

[6] Family archives

[7] Certificate of membership of the French Internal Resistance dated October 4, 1950, Rose Lendower, Dossier French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes,16 P 421 792

[8] Certificate from the Jewish Union for Resistance and Mutual Aid dated February 24, 1947, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[9] Certificate from the National Front for the Struggle for the Liberation and Independence of France, dated December 3, 1950, Rose Lendower, SHD, Vincennes, idem.

[10] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[11] Certificate from the National Front for the Struggle for the Liberation and Independence of France, dated December 3, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[12] Investigation into Rose’s arrest dated February 7, 1952, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[13] Online meeting with Rose’s grandchildren on February 4, 2025.

[14] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[15] Investigation into Rose’s arrest dated February 7, 1952, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem. Archives du Rhône, 3335W

[16] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[17] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[18] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[19] Online meeting with Rose’s grandchildren on January 27, 2025.

[20] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[21] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[22] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem. For the information on the Bergen-Belsen and Raguhn camps, see Anne-Lise Stern’s, Le Savoir-déporté, La librairie du XXIe siècle, Le Seuil, 2004 and Points Seuil.

[23] Application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, French Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, idem.

[24] Record from the rehabilitation center dated March 19, 1951, application for deported resistance fighter status dated December 17, 1950, Rose Lendower, SHD, Vincennes, idem.

[25] Application for political deportee status dated April 7, 1954, Rose Lendower, SHD de Caen DAVCC, idem. French Defense Historical service in Vincennes GR 16 P 421792.

[26] Family archives

[27] Record of compensation payment for political deportees or internees dated July 2, 1956, Rose Lendower, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, idem.

[28] Online meeting with Rose’s grandchildren on February 4, 2025.

Français

Français Polski

Polski