Léa DOMBLATT (née ROZENSWERG) (1889-1944)

Photo of Jean Domblatt and a woman we assume to be Léa Domblatt (since there is no mention of him having remarried after she died) on their family tomb in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris (we took the photo ourselves).

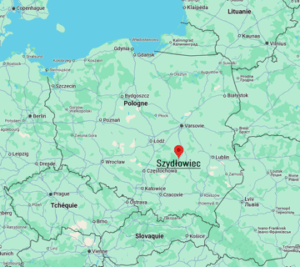

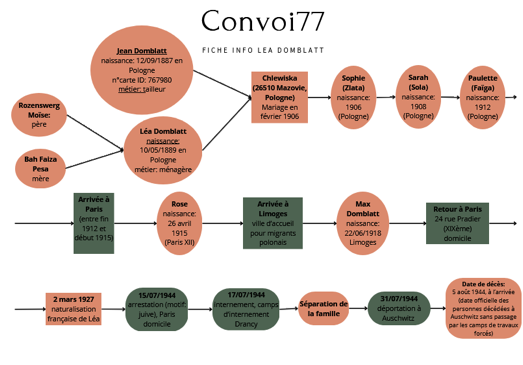

Léa Rozenswerg was born on May 10, 1889 in Szydłowiec, Poland.

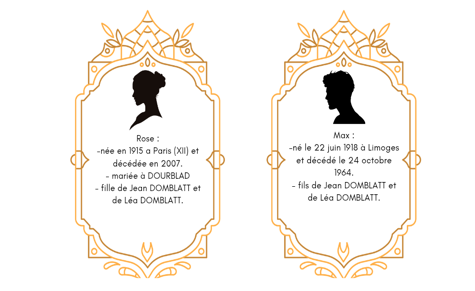

Her parents, both of whom were Jewish, were Moïse Rozenswerg and Faiza Pesa Rozenswerg, née Bah. In 1905, when the people living in the Polish territories controlled by Russia rebelled against oppression and demanded greater freedom, a revolution broke out. The revolt was violent, and included strikes and picketing of numerous factories. Despite the widespread tension in Poland at the time, Léa fell in love and married Joïna Domblatt, also known as Jean Domblatt, in Chlewiska, a town around 5 miles from Szydłowiec. The couple went on to have five children: four girls, Zlata, Sola, Faïga (whose names were later changed to the French versions), Rose and a boy, Max.

Map of Poland showing the town of Szydłowiec (Google Maps)

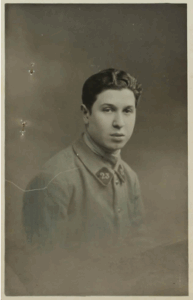

Portrait of Max Domblatt

Source: Domblatt Max, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-876-11

It may have been the turmoil of the revolution that prompted the Domblatt family to flee to France in search of a better life. According to various analyses of Polish emigration to France, most people settled in Paris, where there were plenty of job opportunities as tailors and dressmakers, which was the trade in which her husband Jean worked (according to the Yad Vashem International Holocaust Remembrance Institute website, the town of Szydłowiec was well-known for being home to large numbers of textile and clothing workers). The First World War may have prompted the family to move further south, so that is probably how they ended up in Limoges, in the Vienne department of France. Léa and Jean’s fourth daughter was born in Paris in 1915, while their youngest child, Max, was born in Limoges in 1918. We therefore concluded that the Domblatt family must have left Paris sometime between late 1915 and the first six months of 1918.

The French Museum of Immigration History website says that “after the Great War, in the 1920s, Polish Jews and Turkish Jews who had left the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, along with some Armenians who had survived the genocide, joined the Russian Jews who had arrived prior to 1914 and other needleworkers in Paris. They often lived and worked in the same neighborhood, Belleville”. Our sources reveal that the Domblatt family did not stay very long in Limoges, so it seems likely that they moved back to Paris when the war was over.

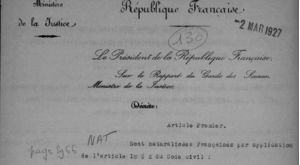

The first record of them after Max was born in 1918 is when Léa and her husband Jean were naturalized as French citizens by decree on March 2, 1927.

Naturalization decree, dated March 2, 1927

www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr

All the sources refer to the same address: 24 rue Pradier in the 19th district of Paris. They must therefore have decided to make this their permanent home.

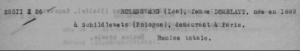

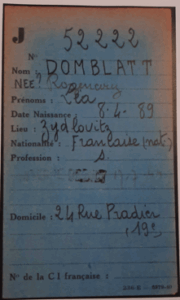

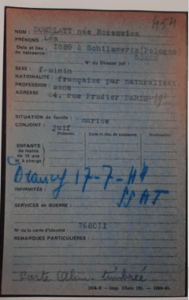

The only records we have of Léa prior to her arrest are two identity cards, dated 1940 and 1941. The Vichy government required all Jews to register themselves with their local prefecture.

The declaration that Léa Domblatt made in the prefecture in 1940

Source: Domblatt Léa, Prefecture file, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5638_040578_L

The declaration that Léa Domblatt made in the prefecture in 1941

Source: Domblatt Léa, Prefecture file, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5609_005647_L

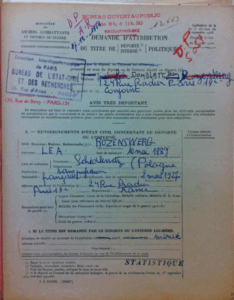

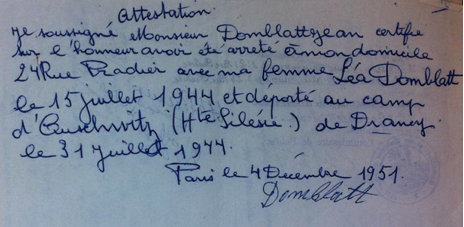

Léa and her husband Jean were arrested at their home at 11.30 a.m. on July 15, 1944, for one reason alone, although it is described differently in the records: one says “racial reasons” while the other says “Israélite”, meaning “Jew”. Two men in civilian clothes, who were associated with the Gestapo, then drove them to the police station in Combat, in the 19th district of Paris. Two people witnessed the arrest: Henri Fleurier (a store owner) and Marie Hembise (the building’s concierge).

Max, their son, had been arrested the previous day, July 14. None of their four daughters were arrested, nor were they deported on Convoy 77. We do not know where they were living at the time.

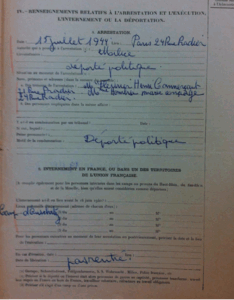

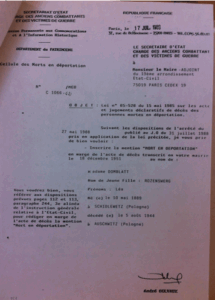

Information given about the arrest in the application for political deportee status for Léa Domblatt (front)

Source: Domblatt Léa, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-444-233-6926

Information given about the arrest in the application for political deportee status for Léa Domblatt (back)

Source: Domblatt Léa, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-444-233-6926

Jean Domblatt’s sworn statement about his arrest and that of his wife

Source: Domblatt Léa, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. DAVCC 21-P-444-233-6926

The arrest took place at a very tense time. The Normandy landings had taken place on June 6, 1944, and the Allies were closing in on Paris. This prompted the Third Reich to step up its policy of deporting as many Jews as possible before time ran out. They organized numerous roundups, including the one involving the Domblatt family. A few days later, children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union générale des israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews) were raided, and most of the children arrested were deported on Convoy 77. In all, 250 children were rounded up from Paris and the surrounding area.

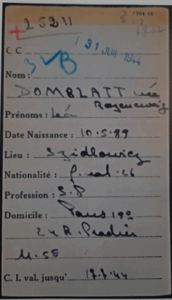

Léa, her husband and their son were initially taken to Drancy, an internment camp north-east of Paris. When they entered the camp, they were assigned three consecutive numbers: Jean’s was 25,210, Léa’s 25,211 and their son Max’s 25,212. The Drancy records also include the rooms in which prisoners in the camp were held. Léa was taken room 2 on staircase 3, while Jean and Max were taken to room 4, also on staircase 3. The letter B, written in blue on their cards, meant that they could be deported immediately.

Léa Domblatt’s record card from Drancy camp

Source: Domblatt Léa, Drancy file, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5688_125367_L

For three years (during the German occupation), Drancy was the main internment camp for Jews who were to be deported from Le Bourget station (1942-1943) and Bobigny station (1943-1944) to Nazi killing centers, mainly Auschwitz. Nine out of ten Jews deported from France passed through Drancy. SS officer Aloïs Brunner was in charge of the camp. He was appointed on June 18, 1943, accompanied by his team of Austrian SS men. When he took over management of the camp on July 2, 1943, he took command of the French gendarmes (military police), who guarded the camp. He also restructured the camp’s internal organization and instilled a climate of terror that was tough on the prisoners, using methods tried and tested in Vienna, Berlin and Salonika. Between then and August 1944, with the assistance of the French gendarmerie, he deported 22,427 men, women and children in less than a year, which was almost a third of all the Jews deported from France. Unfortunately, we have no records or testimonies to attest to Léa’s psychological or physical ordeal during her time in Drancy. Nor do we know when she saw her husband and son for the last time. Were they able to see each other in the camp? Did they have the opportunity to have one last hug?

Photo of Drancy camp, taken in August 1941

(Wikipedia: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-B10919, Frankreich, Internierungslager Drancy.jpg)

Living conditions in the camp were extremely harsh: overcrowding, inadequate hygiene, insufficient food and virtually non-existent medical care. Prisoners were crammed into cramped spaces, often without enough beds, meaning that many of them had to sleep on the floor. Access to water and sanitary facilities was limited, which in turn allowed diseases to spread. Malnutrition was widespread, bringing with it edema and cachexia (emaciation and muscle wastage). Survivors’ testimonies, such as that of Francine Christophe, who was arrested at the age of 8 along with her mother, attest to these appalling living conditions. She recounted how cramped the rooms were and described the lack of food and sanitation. Although we have no direct sources, we can well imagine how difficult and distressing it must have been for Léa.

The rooms in Drancy camp, 1941-1944,

©Shoah Memorial / French National Library Collection

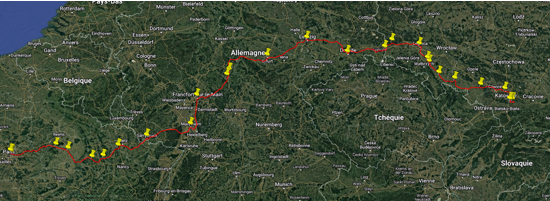

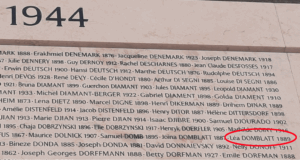

On July 31, 1944, Léa Domblatt, her husband and their son were deported by train from Bobigny station aboard Convoy 77, the last large transport to leave France for Auschwitz-Birkenau. We have no way of knowing whether they all traveled in the same car.

The traveling conditions were too horrific for words. There were a total of 1306 people on the train, including 320 children under the age of 16. More than half of the deportees were French nationals. They were crammed into cattle cars for three days and nights, with barely any food or water. As a result, many people died along the way.

Map showing the route that Convoy 77 took from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau

Source: collections.yadvashem.org

The convoy arrived during the night of August 3 to 4, 1944, at around 3 a.m. The Nazis arranged for the trains to arrive at night, not only to make their activities less visible but also to confuse the deportees. Léa’s official date of death was later deemed to have been August 5, 1944. Like the majority of the deportees, she was sent to the gas chambers shortly after she arrived, along with 850 or so other people.

Her husband Jean survived, and later completed the necessary formalities to update his wife’s civil status and have the words “died in deportation” added to her death certificate.

He also made sure that Léa was posthumously granted the official status of Political Deportee in 1954. This entitled victims and their families to certain rights and compensation, including pensions, financial aid and social benefits to support deportees and their families. As a result, Jean received a payment of 12,000 francs.

Léa’s death certificate, bearing the words “died during deportation”

Source: Domblatt Léa, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-444-233-6926

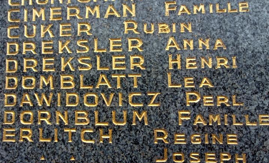

Léa’s name is now inscribed on a memorial stone in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris, alongside that of her husband Jean and their son Max, who are buried there. It also lists the names of some other victims who had previously lived in her Polish home town of Szydłowiec.

The Memorial to the deportees originally from the Polish village of Szydłowiec, who died at the hands of the Nazis, in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris

(our own photo)

Léa’s name on the memorial in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris

(our own photo)

Léa’s name is also inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial de Paris, beside those of her husband, her son and the 75, 565 other Jews deported from France.

The Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

(our own photo)

Our research enabled us to track down some other family members who are related to the Domblatt family by marriage, namely the Livarek family, who are related to Sophie, Jean and Léa’s eldest daughter and Max’s older sister. We are delighted to be able to share our work with them.

We would like to thank:

- The Convoy 77 team, who kindly sent s most of the records that enabled to retrace Léa Domblatt’s life story and write this biography

- The documentation department at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, for making us welcome and supplying some additional records

- The International Institute for the Memory of the Shoah at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, and the Arolsen Archives in Bad Arolsen, for taking the time to answer our questions and provide us with additional records.

- The Paris archives service, the town hall of the 19th district of Paris, and the staff at the Bagneux cemetery

- Everyone else, from near and far, who helped us bring this project to fruition.

We would like to express our most sincere gratitude to Yvette Lévy, a Convoy 77 survivor, who very generously invited us into her home to share her story and give us a better understanding of what the Convoy 77 deportees went through. Meeting her and hearing what she had to say was an incredible opportunity that will be remembered as one of the highlights of this project.

Français

Français Polski

Polski