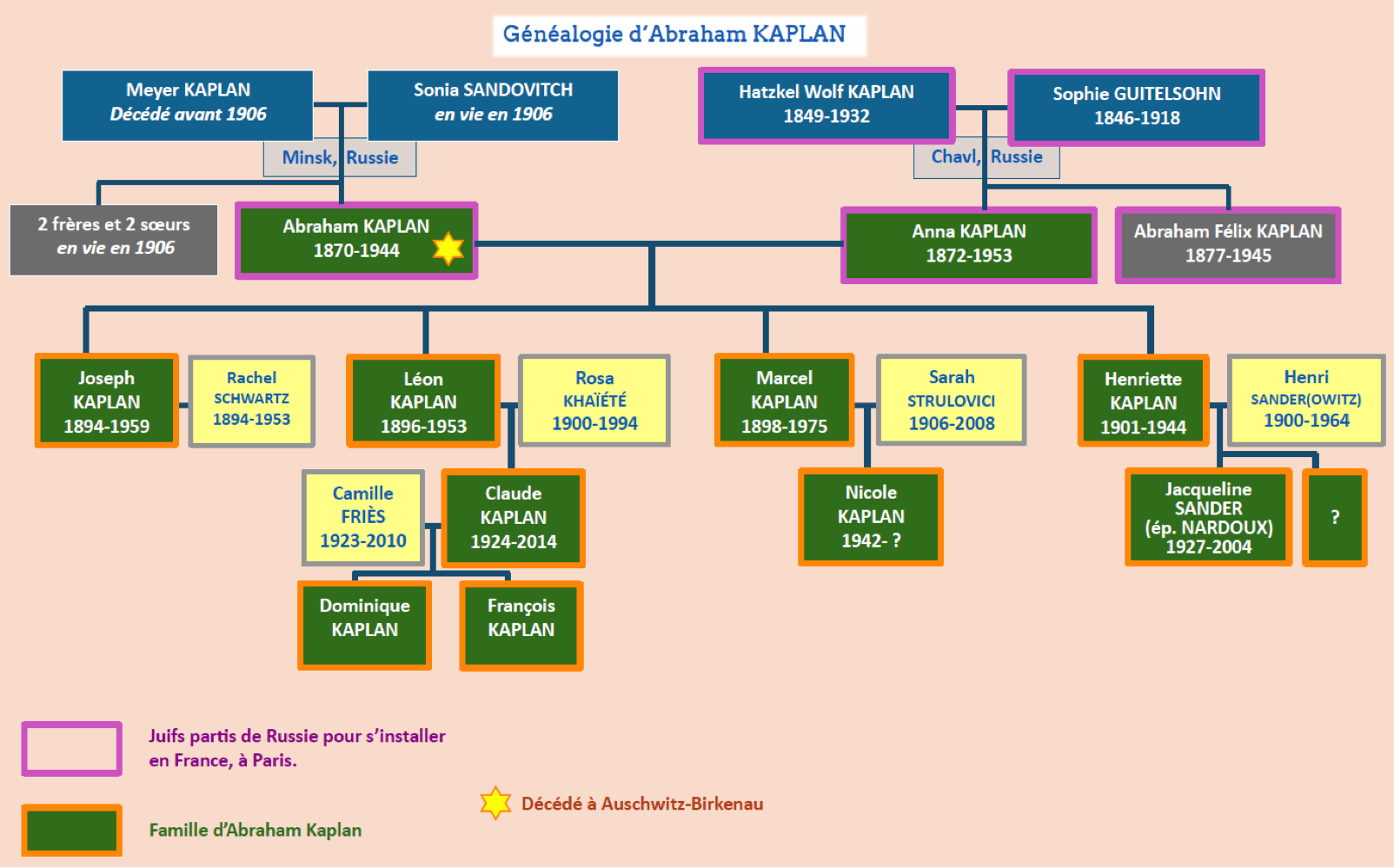

Abraham KAPLAN

This biography was researched and written by Livia Gonzales, Joanna Michel, Pauline Porcher, Alexandra Magré, Lisa Bauduin, Margot Thieffry-Parpaillon, Marion Bonnaud-Delamare, Lucie Richard and Camille Dubois.

From “Yiddish Land” to Paris

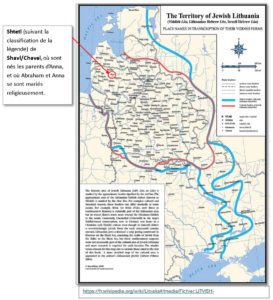

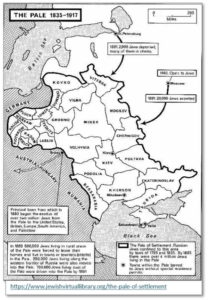

Abraham Kaplan was born into a Jewish family in Minsk (or the Minsk district) in Belarus, which at that time was in the Russian Empire, on March 20, 1870[1]. His application for French citizenship, submitted in 1906[2], reveals that he had two brothers and two sisters still living in “Russia” and that his mother was still alive but his father was dead. His future wife, Anna, née Kaplan, who was also Jewish, was born on October 21, 1872, probably in Chavel, in Lithuania, which was also under Tsarist rule[3]. These areas of western Russia had been annexed in the late 18th century were home to large numbers of Jews, who were obliged to live in a designated “residence zone” (also called The Pale, see the map on the left). The region was thus known as “Yiddish land”.

Abraham Kaplan was born into a Jewish family in Minsk (or the Minsk district) in Belarus, which at that time was in the Russian Empire, on March 20, 1870[1]. His application for French citizenship, submitted in 1906[2], reveals that he had two brothers and two sisters still living in “Russia” and that his mother was still alive but his father was dead. His future wife, Anna, née Kaplan, who was also Jewish, was born on October 21, 1872, probably in Chavel, in Lithuania, which was also under Tsarist rule[3]. These areas of western Russia had been annexed in the late 18th century were home to large numbers of Jews, who were obliged to live in a designated “residence zone” (also called The Pale, see the map on the left). The region was thus known as “Yiddish land”.

Not only was their freedom of movement restricted, but towards the end of the 19th century, Jews were also targeted by pogroms, which were sudden and deadly outbreaks of violence. Abraham and Anna thus grew up in an increasingly insecure environment, and shortly after they were married on June 15, 1893, in a religious ceremony held in “Saveli”[4], they decided to move to France, a country known for making Jews welcome. It appears that Anna’s parents traveled from Chavel to France with them, as they too are listed in a French civil register[5].

The Kaplan family settled permanently in eastern Paris

Abraham and Anna’s first child, Joseph, was born on May 10, 1894 in the 12th district of Paris. We can therefore assume that they arrived to France sometime between when they were married and when Joseph was born, although we cannot be sure of exactly when in the absence of supporting documentation. As their application for French citizenship states that they had been living in France since 1893, they probably arrived between the end of June and December that year[6]. They went on to have two more sons, Léon in 1896 and Marcel in 1898, and then a daughter, Henriette, in 1901.

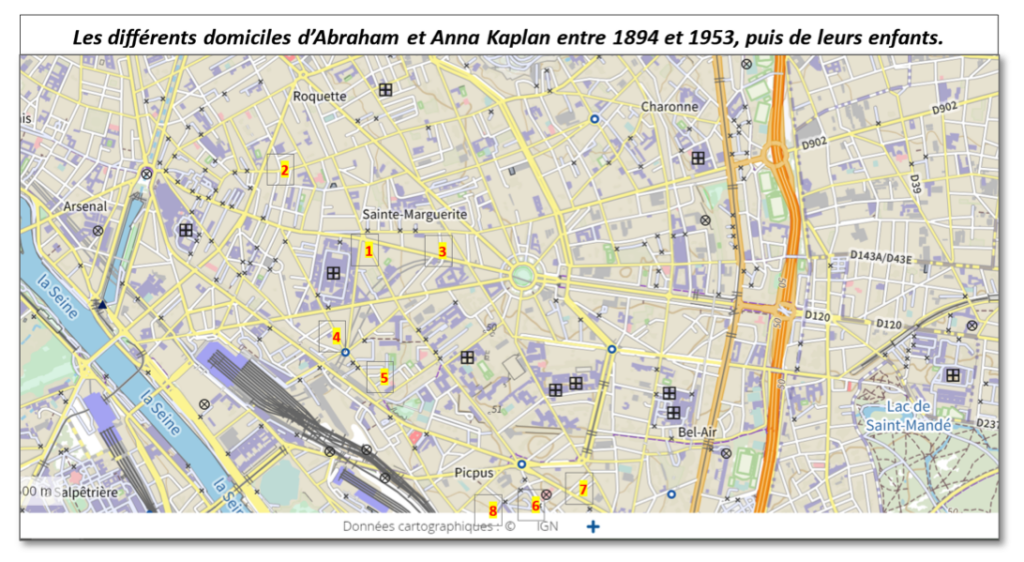

The couple moved home several times as the family grew larger and probably due to Abraham’s work. In 1894, they were living at 18, rue de Reuilly in the 12th district of Paris[7] (1), in 1896, at 57, rue de Charonne in the 11th district (2), and, in 1898 and in 1901 at 287, rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine (3). When Abraham was naturalized as a French citizen, in 1907, he was living at 9, rue Crozatier (4). All these places are centred on the 11th and 12th districts, which were working-class neighborhoods at the time. Abraham was a cabinetmaker and second-hand furniture dealer, and these districts were well known for their many furniture-making workshops.

We have little information about what the family did after the children were born. We assume that they led a fairly frugal life, however, based on the information that Abraham provided when he applied for French citizenship.

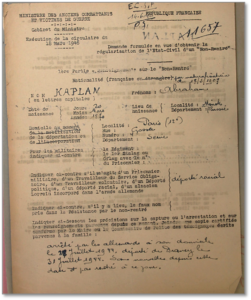

Becoming a French citizen, an understandable ambition for Abraham, although not easy

In 1906, Abraham took an important step; applied to become a naturalized French citizen. A review of his application reveals that some of his family still lived in Russia. He claimed to have completed his compulsory national service there, but we have no way of confirming this. He stated that he wanted to settle in France and not to “get involved in politics.” Anna submitted her application along with his. It seems that there was a problem with processing the file due to the high costs involved. Abraham stressed the fact that he was not a wealthy man: he was a cabinet maker, had four children to support, paid 600 francs in rent plus 75 francs in contributions, paid 520 francs rent for his workshop and declared a weekly income of only 40 francs. In addition, his wife did not work. He therefore tried to negotiate a payment plan or reduced fees. In a letter that he must have had someone else write on his behalf (the handwriting was neat, unlike Abraham’s, whose signature was rather shaky[8]) he begged for a reduction in fees, stating: “(…) as a manual worker, a father of four young children and in poor health, it is impossible for me to pay this sum, it is well beyond my means.”[9]. We were unable to find out anything more about Abraham’s health problems, but they may have been due to what the military authorities noted in his file in 1912, which was referred to as “uneven muscle development”[10]. He therefore offered to pay just 40 francs instead of the usual 70 francs and 25 centimes. Eventually, after waiting for several months and being disappointed time and again because his request for a reduction was repeatedly refused, it was agreed that he should pay 40 francs plus expenses, which meant he obtained a reduction of 6/10th of the original sum. It was also suggested that the four children be granted French nationality immediately, rather than having to wait until they reached the age of majority, in accordance with the Nationality Act of 1889[11].

Abraham therefore officially became a French citizen on March 17, 1907, as did Anna and their four children.

His military service record[12], states that in 1909 he was living at Cité Moynet in the 12th district of Paris(5), and in 1910 at 83 rue Claude Decaen, also in the 12th district (6). It also gives us an idea of what he looked like: he was fairly short, at 5’4”, with brown hair and brown eyes, had an oval face with no distinguishing features, his nose and mouth were described as “medium-sized” and his chin as “round”. This brief description is fairly consistent with the only photo of him that we have, which is on his grave in Bagneux and in which he looks to be about sixty years old.

As a newly-naturalized French citizen, Abraham was called up to register in the military, and had to confirm that he was prepared to defend his recently-adopted country[13].

The First World War: the men of the family mobilized

Seven years after the Kaplan family became French citizens, the men got the chance to prove how grateful they were to their adoptive country by fighting in the First World War.

Abraham had been released from the army reserves on October 1, 1908, because he was over 27 years old. In 1912, he was drafted into to the Auxerre infantry regiment, but on August 31, the Auxerre reform commission, acting on the General’s decision, recommended that he be transferred to the for auxiliary service due to “insufficient muscle development”.

Abraham’s frail physical condition was therefore identified fairly quickly, but this did not prevent the military authorities from enlisting his services in various roles during the First World War. He was called up according to the French mobilization order dated August 1, 1914, and reported for duty on August 3. A special commission that met in Vincennes in October 1914 then placed him on the reserve list of the Fontainebleau infantry regiment. Then, on March 15, 1915, he was assigned to the 22nd Section of Clerks and Administrative Workers in Paris[14]. Between March 1 and July 1, 1917, he was sent to work at 120 rue de Javel in the 15th district of Paris, after which he was to join the 2nd Cuirassiers Regiment. We do not know if he was then sent onto the battlefield, but it seems unlikely. In the end, under Article 5 of a law passed on February 20, 1917, which applied to men who had been discharged or granted an exemption, Abraham, as the father of four children who had previously been deemed unfit for service was sent home on December 10, 1917. He was permanently released from military service a year later, on October 10, 1918, by which time he was 48 years old.

A Paris prefecture record card, issued when the Vichy government was in power, states that Abraham served as an auxiliary for two years during the First World War[15].

Abraham and Anna’s three sons, meanwhile, were drafted into the army as soon as they were old enough to fight, which was normally when men turned 20 but sometimes even earlier, if they were called up in advance. We found their names in the Seine department army recruitment register[16]. Joseph, who was born in 1894, joined the class of 1914, Léon, born in 1896, the class of 1916 and Marcel, born in 1898, the class of 1918. All three fought in the Great War.

Joseph, Léon and Marcel’s service records, which are held in the Paris archives, provide a wealth of information about what they did during the war[17].

Joseph, who was working as a salesman at the time, was mobilized on September 13, 1914[18]. As a 2nd class private in the 94th infantry regiment, he fought on the front line. His file includes a description of his appearance: he was 5’6” tall with dark brown hair, blue eyes, a broad forehead, a strong nose and a long face. He was wounded in action in Ypres on December 18, 1914, when a bullet hit him in the right eye. As a result of this injury, he was discharged in February 1915 “for enucleation of the right eye”. In July 1915, he was commended for his good behavior in the line of fire and was awarded the Military Medal and the French War Cross with a palm. Starting in February 1916, he drew a retirement pension of 620 francs.

Léon, who was listed as a “salesperson/representative” was mobilized in April 1915[19]. Also a 2nd class private, he was drafted into the 139th Infantry regiment. He was a little taller, at around 5’8”, had blond hair, brown eyes, no hair over his forehead, a straight nose and an oval face. From 1915 to 1918, he courageously went back and forth between the front and hospitals. He was eventually placed on auxiliary duty in March 1918, as the reform commission deemed him “unfit for service” due to heart problems[20] and poor health in general. He was demobilized on April 17, 1919, and was awarded a certificate for good conduct.

Marcel, who was a turner-toolmaker and was still living with his parents, enlisted voluntarily at the town hall of the 12th district of Paris in April 1917[21] for a period of four years[22]. He too was a 2nd class private, first in the 121st and then in the 109th Heavy Artillery regiment. After the signature of the armistice, he was transferred to the train squadron, in which according to the records, he was still serving in December 1919. He seems to have run into some problem in the army, perhaps because he felt that demobilization was too long coming[23], but whatever the reason, he “was kept in the corps as a disciplinary measure for 45 days”. He was finally allowed to return home on May 29, 1921, but was not awarded a good conduct certificate. However, he did receive a joint commendation for having served in the 109th Heavy Artillery regiment under the “energetic command” of Squadron Leader Grollemund.

It is truly incredible that none of the Kaplan brothers were killed during the First World War, which claimed so many victims. They all served for France so courageously, no doubt in the belief that they were fulfilling a duty to a country that had opened its arms to their family and that had become their home.

The Kaplan siblings, families firmly rooted in the east of Paris

Shortly after the war, the Kaplan children began to leave the family home and get married. Joseph was the first, in 1922, followed by Léon and Henriette in 1923, and lastly Marcel, in 1926.

The 1926 census reveals that Marcel was then the only one still living with his parents at 81 rue Claude Decaen (no. 6) in the 12th district of Paris. Abraham is listed as a “furniture dealer (business owner)”, Anna as a “fabric dealer (business owner)” and Marcel as a “wooden goods salesman”. This suggests that the parents were self-employed and that Marcel may have been working with his father[24]. After their last child left home, Anna and Abraham moved to 4 rue Gossec (7). We don’t know exactly when this was, but it must have been between 1931 and 1936, because the 1931 census lists them at 81 rue Claude Decaen, and by 1936 they were living at 4 rue Gossec[25].

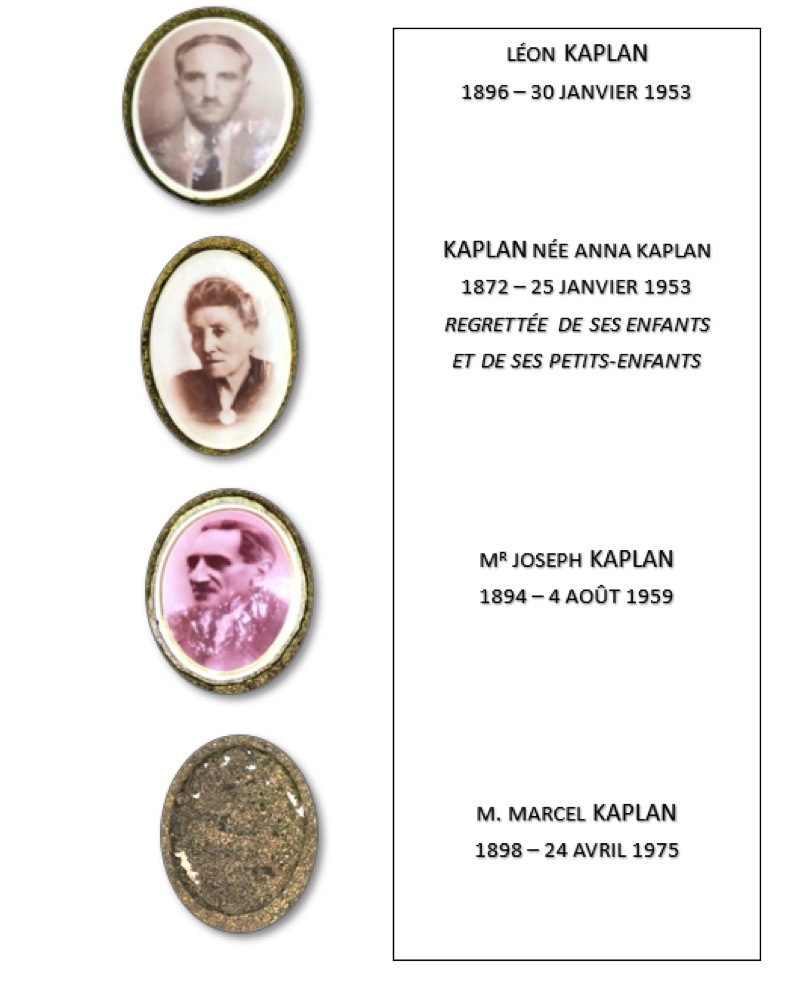

Joseph, the oldest child, married Rachel Schwartz, 28, who had been a widow since 1918, on February 2, 1922[26] and moved into the house where she had lived with her first husband[27], at 22 de la rue Titon in the 11th district of Paris. No children are listed in the 1931 census, and given that Rachel was 41 at the time, it is unlikely that they had any after that. In 1938, according to his voter registration card, and at the time of the 1946 census, Joseph was living at 25 rue Alexandre Dumas, also in the 11th district. He was working at the time, but his wife Rachel, was not. She died at home on April 1, 1953 at the age of 59. Shortly after his mother died, then his brother Léon in January 1953, and then his wife in April of the same year, Joseph moved to 4 rue Gossec, into his parents’ old apartment, which was nearer to where his brother Marcel lived. By April 1953, Marcel and Joseph were the only two of the four siblings still alive.

Joseph died at the age of 65 on August 4, 1959 at the age of 65, in the 15th district of Paris. He is buried in the Bagneux cemetery, now in the Hauts-de-Seine department of France[28].

Léon, the second brother, married Rosa Khaiëté, who was born in 1900, on May 24, 1923. They initially lived at 9, rue Ebelman in the 11th district of Paris, and then, according to his 1927 voter registration card and the 1931 and 1936 censuses, at 19, rue de la Brèche-aux-Loups in the 12th district (8). They had one child, Claude Armand, who was born on April 24, 1924[29] in the 12th district. Léon died in hospital at 1:00 a.m. on January 30, 1953, at the age of 56. His mother, who had died a few days previously, was buried on the same day. Léon’s death certificate states that he was a street vendor, so no doubt worked on the markets[30].

Marcel, the third brother, married Sarah Strulovici on October 20, 1927 at the town hall of the 4th district of Paris. The couple had one daughter, Nicole, who was born in 1942[31]. Marcel also lived on rue de la Brèche-aux-Loups, at number 21 (8), so not far from his brother[32]. He lived there until his death in 1975. He appears to have worked in various different jobs, as a turner[33], a sales representative[34] and as a fabric-dyer[35]. As for Sarah, she was a secretary for a furniture designer and manufacturer called “Paul Giordano”[36] at 22 rue Marchoulan. Sarah died in Hamburg, Germany in 2008, at the age of 101.

When Abraham and Anna moved to 4, rue Gossec between 1931 and 1936, it was no doubt in order to live nearer to Léon and Marcel.

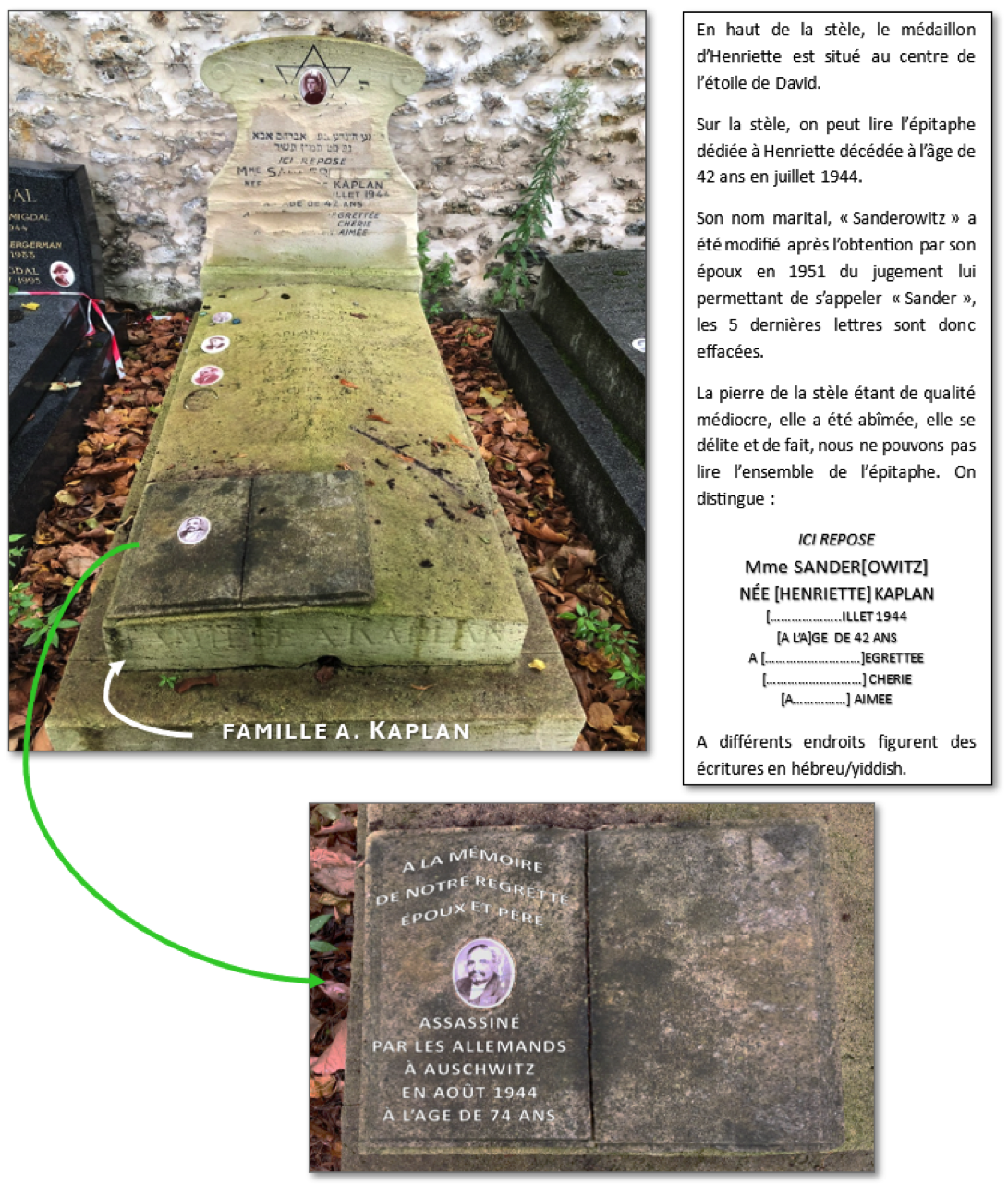

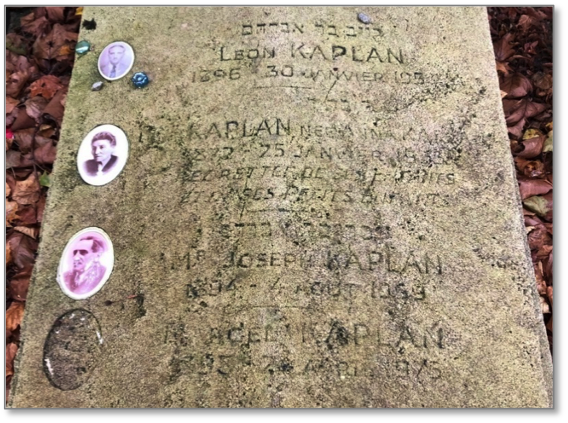

Henriette, the youngest of the siblings, left the family home when she married Henri Sanderowitz[37], on October 25, 1923. According the marriage certificate, he was a dental technician and Henriette was not working at the time. They had one daughter, Madeleine Jacqueline Sander[38], who was born on July 28, 1927 in the 12th district of Paris. According to Henri Sanderowitz’s voter registration card from 1939, they were then living at 54, Boulevard de Reuilly in the 12th district. We know very little about Henriette, other than that she died at the age of just 42, in July 1944, shortly before or at the same time as her father was arrested. We do not know how or why she died, but we wonder if the two events were linked in some way. The Bagneux cemetery burial register states that her remains were brought there from Etampes, which is about 30 miles south west of Paris. She was buried on November 18, 1945, over a year after she died, in what would later become the family vault[39]. On the headstone, there is a photo of her with a Star of David around it[40]. The family had a special tribute to Abraham added on the lower left of the tombstone.

The Second World War, the German Occupation and Abraham’s arrest

In 1939, the Kaplan brothers had to face yet another war. Joseph, who was already drawing a war pension due to injury, was not called up, but he was not finally released from military service until June 6, 1943. Léon, a who was still in the reserves, was mobilized on September 2 and assigned to wartime train depot no. 19, which was in charge of managing train units for various divisions. Marcel was discharged by a commission in Meaux on the grounds of poor health[41].

We were able to find out very little about what happened to the family during the war, in particular during the Occupation.

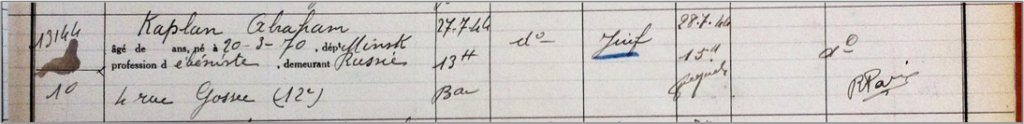

In 1944, Abraham and Anna were still living at 4, rue Gossec. Anna must have been out, or have gone into hiding elsewhere, when, according to the arrest register, the Germans arrested Abraham at his home at 1:00 p.m. on July 27. The following day at 3:00 p.m., he was taken to Drancy internment camp.

French Police arrest register. Source: Paris Police Headquarters, ref. KAPLAN-Abraham-APP_CC2-9.

According to his Drancy record card, when Abraham first arrived in the camp, he had 4800 francs confiscated from him[42], which was a significant sum of money at the time. In 1944, the average salary in the city was 1650 francs a month[43], so Abraham probably took with him all the couple had in savings.

Anna was not at home when Abraham was arrested, as we said above, so we suppose that she had gone into hiding elsewhere. She might have been staying with one of the children, or she could have fled Paris with them. None of the other family members were caught either, which is surprising given that they were such a large family and all lived in areas of Paris where the most round-ups took place, in particular the 12th district, where the arrest rate was the highest in the capital[44]. Of the five Kaplan families, only the father, Abraham, was arrested. We surmise therefore that the rest of the family must have gone into hiding somewhere outside Paris. Henriette died in July 1944 near Etampes, so it is possible that some of the Kaplan family had taken refuge there. It appears that Abraham, either because he was unable to move or because he wanted to keep an eye on the apartment and their property, chose to stay behind in Paris. Either way, the rest of the family members managed to escape with their lives, narrowly avoiding death at the hands of the Third Reich.

On July 28, the day after he was arrested, Abraham was interned in Drancy, which from August 1941 to August 1944 was the main hub of France’s anti-Semitic deportation policy. Nine out of ten Jews who were deported passed through Drancy before being deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Abraham was interned on grounds of his “race” until July 31, when Convoy 77 set off for the concentration and extermination camp.

Abraham was 74 years old at the time, meaning he had no chance of surviving deportation. The convoy arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 3. He was later declared to have died on August 5, 1944. He was probably murdered in the gas chambers but, given his advanced years, he may not even have survived the journey in such appalling traveling conditions.

The formalities undertaken by the Kaplan family

On June 14, 1946, Anna applied to have Abraham formally declared a “non-returned” person. This was an essential prerequisite for what lay ahead. The certificate states that Abraham was “deported on racial grounds”, but there is handwritten paragraph that contains a mistake, or perhaps just a slip of the pen: it says that he was arrested by the “Germans”, when in fact he was arrested by the French police.

Request to have Abraham declared a “non-returned” person.

Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref., 26296-KAPLAN_Abraham_21P_467_955_26296_DAVCC_copyright_0029

Abraham’s death was recorded in the civil register on August 28, 1946. In the 1950s, the Kaplan family embarked on the necessary administrative procedures to have his death acknowledged to have taken place as a result of the Vichy government’s policy of collaboration with the Nazis. In 1952 and 1953, a series of laws and decrees were passed in France, which provided for compensation to be paid to deportees who had survived or the beneficiaries of those who had died. On July 22, 1952, Anna, Abraham’s wife and thus his legal heir, submitted a request to have him recognized as a “political deportee”, which would entitle her to financial compensation and honor his memory to a certain extent, but not acknowledge that he had been deported on grounds of his “race”, in other words, because he was Jewish. Since 1948, there had only been two officially recognized categories of deported persons: “deported Resistance fighters” who were granted the same rights and benefits as members of the armed forces and “political deportees”, who were classed as civilian victims[45]. Despite the fact that the Vichy government police register includes the word “Jew” in the column “reasons for arrest”, the French state took several years to admit its role in this racist policy[46]. Abraham was finally granted “political deportee” status on January 17, 1955, almost three years after Anna’s request[47].

Anna and Léon died just four days apart, on January 25 and 30, 1953 respectively, and before the formalities were completed. Anna was 81 years old, and probably died of old age, especially as the death certificate states that it is not known what time she died, so presumably it was while she was asleep. Her son Léon, who was 57, died a few days later[48], the night before she was buried. Anna’s death must have hit him hard. He had a long-standing heart problem[49]: perhaps the news of her death was just too much for him to bear.

On January 30, 1956, Joseph and Marcel, who by then were the only two children still alive and had become Abraham’s only remaining heirs after their mother died, each received compensation of 5,400 francs for the loss of their father[50].

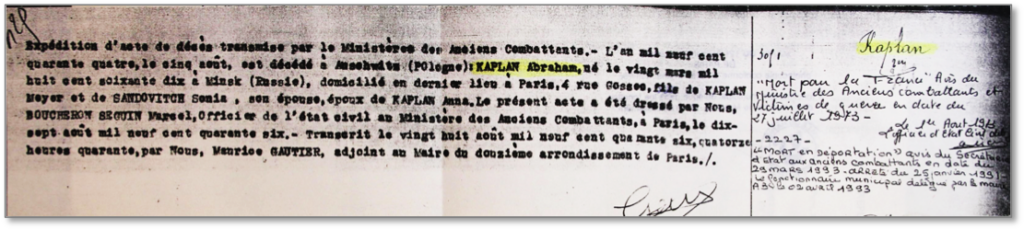

In 1961, Marcel, Abraham’s youngest son, persevered with the formalities by going to the Ministry of Veteran Affairs and War Victims in order to find out the date and place where the death had been registered, or failing that, to get a copy of the missing person’s certificate, so he could apply for a death certificate. In December 1961, he received notification that the details had been recorded in the civil register at the town hall in the 12th district of Paris. On July 27, 1973, the Ministry for Veterans Affairs and Victims of War granted Abraham the official status of “Died for France”, and this was duly signed by the mayor of the 12th district on August 7. Each time there was any change in Abraham’s status, the registrar was informed and noted the details on his death certificate. Marcel was the only one still alive by then and he knew that at least his father had been posthumously recognized as a Holocaust victim, the culmination of a long process that his family had begun soon after the war. Sadly, however, Marcel did not live long enough to see his father officially recognized as having been deported simply because he was Jewish.

The French government remains committed to honoring the Jewish victims of the Vichy regime, historians continue their research and the few remaining survivors continue to testify about their experiences[51]. Hence, on March 29, 1993, the French government formally acknowledged that Abraham had “Died during deportation” and a note was added in the margin of his death certificate, originally issued on August 17, 1946. This serves as a testament to the tragic fate suffered by the victims of the genocide.

Abraham Kaplan’s death certificate. Town hall of the 12th district of Paris

Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. KAPLAN-Abraham-DAVCC-21P-259-807-2

The family vault and memorials to Abraham

Photos of the Kaplan family vault

Photos of the Kaplan family vault

The inscription on the vault confirms that Abraham’s entire family is buried there. The photo of Abraham must have come off at some point, so is now no longer visible.

Abraham’s family lost no time in paying tribute to him. In November 1945, when Henriette was buried in the Bagneux cemetery, they put a memorial in the form of an open book on the tomb. There are inscriptions on both pages. They are no longer entirely legible, but we have been able to work out what it says. On the left, there is an epitaph in French with a photo of Abraham in the center, and on the right, some text in Hebrew/Yiddish.

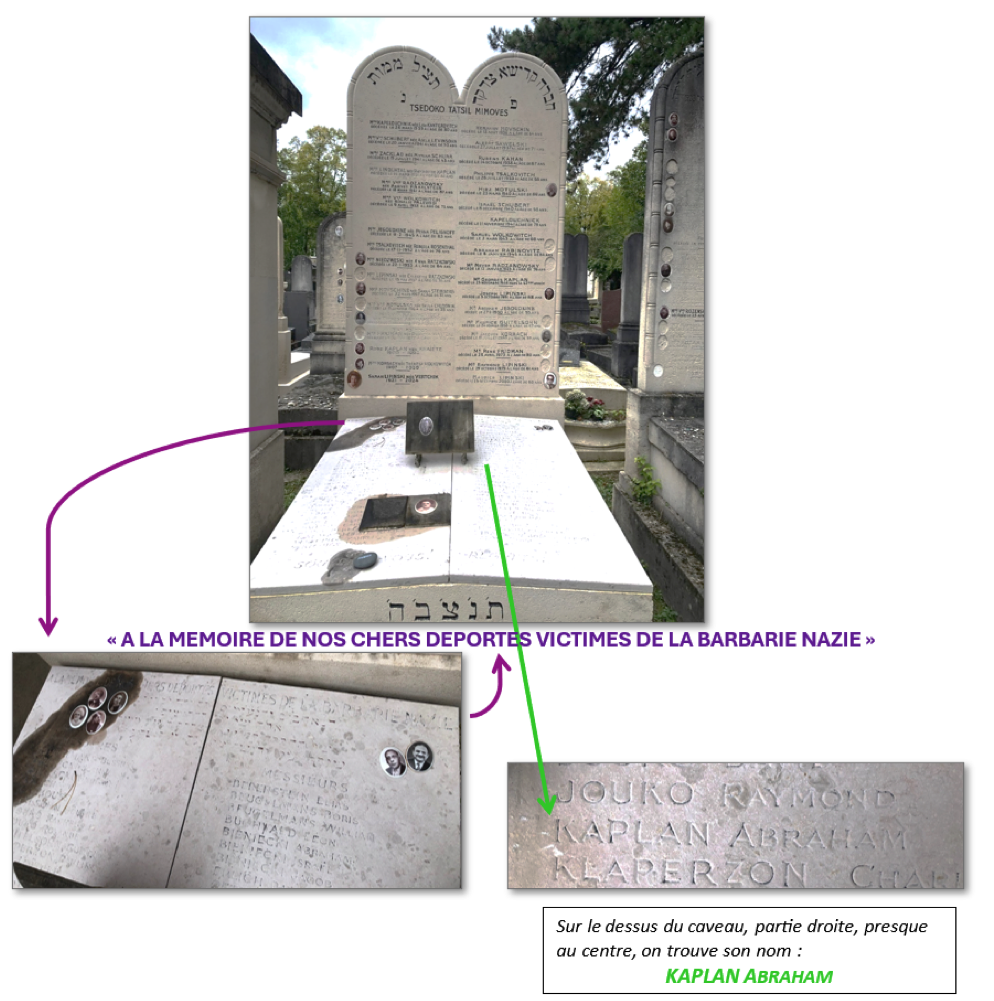

In another part of Bagneux cemetery, the Jewish charity Tsedoko Tatsil Mimoves has erected a memorial that bears the words “In memory of our dear deportees, victims of the Nazi barbarism”, on which Abraham’s name is inscribed. Numerous Jewish charities have paid tribute to the people who died during the Holocaust by erecting such memorials and engraving their names in stone, even though there is nothing left of their remains.

Even though Abraham was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau and is not buried alongside his family, his wife and children felt it was important to honor his memory, not only by dedicating the family tomb to “A. Kaplan,” but also by including a tribute to him on the top of the tomb. In this way, it was as if he were with them in spirit, and they could visit the grave to pay their respects. Jewish charitable organizations also played their part in keeping the memory of Abraham alive by including his name on the memorial to deported Jews in the Bagneux cemetery.

Chronology:

-

- March 20, 1870: Abraham Kaplan was born in Minsk, in tsarist Russia (now Belorussia) (son of Meyer Kaplan and Sonia Sandovitch), Jewish.

- October 21, 1872: Anna Kaplan was born in Kowna[52] (or in the Kowna district, which included the shtetl in Chavel) in tsarist Russia (daughter of Matszer[53] Kaplan and Sophie Guitelsohn[54]) Abraham’s future wife, also Jewish.

- June 15, 1893: Abraham Kaplan (age 23) married Anna Kaplan (age 21), in “Saveli”[55].

- [We do not know when they arrived in France, but it must have been between June 15, 1893 and May 10, 1894, perhaps with Anna’s parents and Anna’s brother.[56]]

- May 10, 1894: Joseph was born[57]. HIs parents were then living at 18 rue de Reuilly, in the 12th district of Paris.

- February 13, 1896: Léon was born[58]. The family was then living at 57 rue de Charonne, in the 11th district of Paris.

- July 20, 1898: Marcel was born[59] . The family was then living at 287 rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine , in the 11th district of Paris.

- October 2, 1901: Henriette was born[60]. The family was still living at 287 rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine, in the 11th district of Paris.

- March 17, 1907: Abraham became a French citizen, as did his wife and children. When the made the application (1906), and when it was approved, the family was living at 9 rue Crozatier, in the 12th district of Paris.

- 1909: The family lived at Cité Moynet in the 12th district of Paris.

- 1910: The family lived at 83 rue Claude Decaen in the 12th district of Paris.

- Between 1914 and 1918: Abraham was called up and served as an auxiliary during the First World War. His sons were all in the army and involved in the fighting.

- July 27, 1944 at 1 p.m.: The French police arrested Abraham at his home at 4 rue Gossec in the 12th district of Paris. He was detained until the following day, when he was sent to Drancy (he left for Drancy at 3 p.m. on the 28th).

- July 28, 1944 to July 31: Abraham was interned in Drancy on grounds of his “race”.

- July 3, 1944 – August 3, 1944: Abraham was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- July 1944: Death of Henriette Kaplan (married name Sanderowitz), Abraham’s daughter, at the age of 42.

- August 5, 1944: Official date of Abraham’s death. However, the convoy arrived at the camp on August 3 and the selection took place immediately, so we can safely assume that he was killed that same day, or on August 5 at the latest.

- April 2, 1946: Anna received a provisional information certificate summarizing what was known about Abraham’s deportation so that she could get started on the necessary administrative formalities.

- April 13, 1946: The Ministry sent Anna certificate confirming that Abraham had not returned from the camps.

- April 25, 1946: A notary drew up an affidavit to certify that Anna was indeed Abraham’s wife, their (religious) marriage having taken place in Russia. She also had to provide proof of their having become French citizens by submitting a certificate of nationality.

- August 17, 1946 – August 28, 1946: Abrahams death certificate was entered into the civil register.

- July 22, 1952: Acknowledgement of receipt of Anna’s application for political deportee status for Abraham Kaplan.

- January 26, 1953: Anna died at her home.

- January 30, 1953: Léon died in hospital the night before his mother was buried.

- January 1955: Abraham was officially declared to have been a “political deportee”.

- May 9, 1955: In the presence of a notary, Marcel appointed his brother Joseph as his legal representative to settle the estate of Abraham Kaplan, who died in deportation. The notary forwarded this request to the Ministry on May 14.

- January 30, 1956: The State paid “compensation” for the loss of Abraham (the cheque was payable to the surviving beneficiaries, Joseph and Marcel).

- November-December 1961: Marcel went to find out the date and place where Abraham’s death had been registered. He was able to obtain a copy of the death certificate issued in 1946 at the town hall of the 12th district of Paris.

- July 27, 1973: Abraham was officially granted the title “Died for France”.

March 29, 1993: Abraham was officially granted the title “Died during deportation”.

Sources & references

[1] Abraham Kaplan’s death certificate, Paris Archives.

[2] File on KAPLAN_Abraham_BB11BB11_4489_4001x06_A_N (11).

[3] File on KAPLAN_Abraham_BB11_4489_4001x06_A_N (9)

[4] This is the name that is listed on official documents drawn up in France, for example on Anna Kaplan’s affidavit drawn up on April 25, 1946. Source: KAPLAN-Abraham-DAVCC-21P-467-955-31. We were unable to find any reference to the name “Saveli”, but we believe it to be a misspelling of the name of a shtetl, Chavel/Shavel/Chavli in Russian, which is located north of Kowno (Kaunas) (see map The Territory of Jewish Lithania) and is now the city of Šiauliai, in Lithuania, and was also where Anna’s parents were born.

[5] Anna’s parents are buried at the Bagneux cemetery. Her father, Hatzkel Wolf Kaplan, was a rag and bone man. He died on April 26, 1932, at the age of 82. His wife, Svie/Sophie Guitelsohn, died on October 16, 1918, at the age of 72. Anna’s brother, Abraham Félix (known simply as Félix), also lived in Paris. He was a tailor and had a store at 170 rue de la Convention in the 15th district of Paris.

[6] Application for French citizenship. Source: KAPLAN_Abraham_BB11_4489_4001x06_A_N-9.

[7] See the various addresses on the map.

[8] Also, Abraham’s army service record states that his educational level was “0”, meaning that he could neither read nor write.

[9] File on KAPLAN_Abraham_BB11_4489_4001x06_A_N-7.

[10] This led to him being recommended for auxiliary service. Digital archives of Paris, Abraham Kaplan’s army service record. Source: archives_FRAD075RM_D4R1_1433_0748_D.

[11] A law that brought in the possibility of granting French citizenship to the whole family when the father was naturalized as a French citizen.

[12] Abraham Kaplan’s army service record: archives_FRAD075RM_D4R1_1433_0748_D

[13] Article 12 of a French law dated March 21, 1905 was amended as follows: “Individuals who become French by naturalization, reinstatement or declaration made in accordance with the law are entered on the list for the first class to be incorporated after their change of nationality”.

[14] The COA, Clerical and Administrative Workers sections, working alongside other administrative staff, were among the main units responsible for organizing train movements and crews.

[15] An entry on a card from the Prefecture of Paris, which is based on his service record, states that he took part in the campaign against Germany from March 15, 1915 to December 10, 1917.

[16] Paris digital archives, Kaplan Joseph, 1914, 4th bureau, main list, serial number 2898; Kaplan Léon, 1916, 4th bureau, main list, serial number 2627; Kaplan Marcel, 1918, 4th bureau, main list, serial number 2740.

[17] Their educational level was “3”, which meant that they had completed elementary school but had not passed the elementary school leaving certificate tests.

[18] Paris digital archives, service record for Joseph Kaplan archives_FRAD075RM_D4R1_1817_0937_D.

[19] Paris digital archives, service record for Léon Kaplan archives_FRAD075RM_D4R1_1938_0298_D.

[20] More specifically, “endocarditis, mitral valve insufficiency, systolic murmur” and “significant cardiac instability with no lesions to the heart”.

[21] Paris digital archives service record for Marcel Kaplan archives_FRAD075RM_D4R1_2072_0575_D.

[22] This four-year voluntary commitment at this stage of the war appears to be strategic rather than a patriotic gesture, as had been the case right at the start of the war, as volunteers could choose which army corps they wanted to join. Marcel, knowing that he would be mobilized and probably assigned to the infantry, probably decided to volunteer to serve in the heavy artillery regiment, which was stationed further back from the front line in order to avoid the most dangerous offensives, such as those led by General Nivelle. From Philippe Boulanger, “Les conscrits de 1914: la contribution de la jeunesse française à la formation d’une armée de masse” (“The conscripts of 1914: the contribution of French youth to the formation of a mass army”) in Annales de démographie historique, 2002, n° 1, pp. 24-26

[23] The demobilization of French combatants from the First World War took place over a period of 19 months, from November 16 to June 14, 1920.

[24] 1926 census. Paris digital archives.

[25] Abraham’s voter registration card, issued in 1937, also lists this address.

[26] Joseph and Rachel’s marriage certificate, town hall of the 14th district of Paris, Paris digital archives, archives_AD075EC_14M275_0043.

[27] Rachel Schwartz was married in the 11th district of Paris to Moïse Casviner, a Jew from Romania, on May 1, 1916 (certificate no. 613, Paris digital archives). He died at their home on rue Titon, aged 27, on May 17, 1918.

[28] Bagneux cemetery, family vault, Division 115, Ros 2, n° 19, 161 CT 1944, 1st section. See photos of the vault at the end of the biography.

[29] Husband of Camille Marie Mathilde Denise Friès (1923-2010), who died at the age of 90 in Poissy in 2014. According to the Généanet website, Claude and Camille had two sons, Dominique and François Kaplan.

[30] The census registers list his job as “representative”.

[31] 1946 census. Paris digital archives.

[32] 1931 and 1936 censuses. Paris digital archives

[33] 1921 voter registration card. Paris digital archives.

[34] 1931 census. Paris digital archives.

[35] 1936 census. Paris digital archives.

[36] Exact title “stenotypist” at “Giordano, 22 rue Marchoulan”, 1936 census. Paris digital archives.

[37] Marriage certificate n° 1559. Paris digital archives.

[38] Her birth name was “Sanderowitz”, but in 1951 her father was granted a court order to change it to “Sander”. The family gravestone in the Bagneux cemetery bears the names of Henri Sander and Jacqueline Sander, and it appears that Henriette’s daughter chose to use her middle name.

[39] Division 115, Row 2, n° 19, 1st section, 161CT.

[40] See the photos at the end of the biography.

[41] It lists “multiple subcutaneous tumors, poor general condition, blood urea 0.96.” Service record for Marcel Kaplan archives_FRAD075RM_D4R1_2072_0575_D.

[42] Drancy interment card. In 1944, the average salary in the city was estimated at 1650 francs (https://www.resistance60.fr/salaires), so the money Abraham had on him when he was arrested may have been the couple’s entire savings.

[43] https://www.resistance60.fr/salaires.

[44] Laurent Joly reports that it is 63%, mainly due to the zealous nature of Henri Boris, the police chief who was responsible for arresting Jews in this district. Laurent Joly, “Vichy et la Shoah” (Vichy and the Shoah), in Nouvelle Histoire de la Shoah, ed. A. Bande, P.-J. Biscarat and O. Lalieu, Paris, 2021, pp. 150-151.

[45] Olivier Lalieu, “La mémoire de la Shoah en France” (The memory of the Shoah in France), ibid., p. 217

[46] However, it should be noted that in the application file for the title of political deportee filed in 1952, in chapter V – Information relating to the reasons for execution, internment or deportation, the term “racial deportee” was added.

[47] Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 26296-KAPLAN_Abraham_21P_467_955_26296_DAVCC_copyright_0004.

[48] He died at the Salpêtrière hospital, Paris digital archives, death certificate 788, town hall of the 12th district of Paris.

[49] See previous note and the entry on his service record.

[50] Payment confirmed on January 30, 1956, and paid by a money order for 10,800 francs. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 26296-KAPLAN_Abraham_21P_467_955_26296_DAVCC_copyright_0005.

[51] Olivier Lalieu, “La mémoire de la Shoah en France” (The memory of the Shoah in France), ibid., pp. 224-229.

[52] Now Kaunas in Lituanie.

[53] Or Hatzkel Wolf Kaplan, born in 1847, at Chavelsk (Russia/Poland), fabric merchant, died in Paris on April 26, 1932. Source Généanet.

[54] Also spelled Guitelzohn or Guitelsohn.

[55] Placename used on the couple’s official paperwork, but which is probably a corrupted form of Anna’s parents’ birthplace, Chavel, a town in Lithuania in the Russian Empire, which was pronounced “Chavli” in Russian, later spelled “Saveli”in France. It is now called Šiauliai, and is located some 75 miles north-northwest of Kaunas.

[56] Death certificate n° 820, town hall of the 4th district of Paris, dated 1932 on which Anna’s brother, Félix (real name Abraham Félix), is listed as a witness.

[57] Paris digital archives, birth certificate 1302, town hall of the 12th district of Paris, 1894.

[58] Paris digital archives, birth certificate 658, town hall of the 11th district of Paris, 1896.

[59] Paris digital archives, birth certificate 2244, town hall of the 11th district of Paris, 1898.

[60] Paris digital archives, birth certificate 4230, town hall of the 11th district of Paris, 1901.

Français

Français Polski

Polski