Biography of Paulette Bloch

There is only one biography for her and her mother Fernande, the tragic end of whom she shared, and her sister Madeleine, who survived.

In memoriam of the Bloch family

Written by Jean-Pierre Lehman in March, 2017

List of the teachers at the Lucien de Hirsch school deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944

My grandmother, Berthe Hayem, married name Lehman, was the first cousin of Jeanne and Fernande Hayem. They were all three born at the end of the nineteenth century – Berthe at Rosières-aux-Salines and the two sisters at Verdun [1].

They were very close during their childhood and adolescence. Once married, Berthe and Jeanne would remain in Nancy. Jeanne married Armand Horviller and had no children. My grandparents raised five boys — Lucien, André, Georges, Paul and Pierre. Fernande left eastern France to settle in Paris, where she met Charles Bloch, with whom she had two daughters – Madeleine and Paulette.

These three families were to be largely swept away in the Shoah. Only Berthe, André, Georges and Madeleine survived.

With these few lines I wish to honor:

the memory of the Bloch, Hayen, Horviller, and Lehman families.

the memory of Rosalie, Denise, Tauba, Anna, Esther, Marcelle, Sara, Marie and Syma, who accompanied the children of the Lucien de Hirsch school to the death camps [2].

__________________

In the 1950’s my parents took me to play in the Buttes Chaumont park. Quite often on the way back we paid a visit to Madeleine at n° 70 avenue Secrétan. I still remember the wooden staircase that led upstairs, the student infirmary where the pupils, who were a bit older than I was, rested and recharged their batteries. They lived at the school. I could feel their life was different from mine; their parents never came to visit them….

André (my father) and Georges Lehman (my uncle), who knew the Bloch, Hayem and Horviller families, are still alive. 93 and 91 years old, respectively, they experienced these grim events. Madeleine and Paulette belonged to their generation; they played together in Nancy, not far from the synagogue.

__________________

This piece could not have been accomplished without the help of the Jewish genealogical society, the Mémorial de la Shoah, and the Lucien de Hirsch school.

Our thanks here to them all.

Madame Marianne Picard, who was the dynamic principal of the Lucien de Hirsch school from 1950 to 1992, relates in her book dedicated to the 90-year history of the school [3]: “In the night of July 24, 1944 one hundred seven children and their teachers were arrested at the school and deported to the Nazi extermination camps. Not a single child came back, and only Madeleine Bloch was to survive.” The plaque placed on the entrance of the school bears witness [4]:

The surviving teacher was Madeleine Bloch.

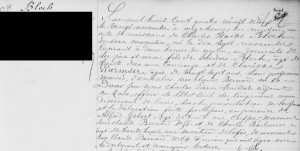

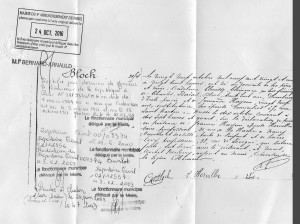

Her father, Charles Bloch, born in Paris in 1882, had been one of the youngest teachers at the school. Here is his Paris birth certificate of November 20, 1882.

|

This photo, taken in 1900, shows M. and Mme Benoît Lévy [5], who headed the school from 1901 to 1935, sitting in the front row. Charles, standing with his arms crossed, was 18 years old.

In 1901 he did his military service. His colleague, Nathan Schentowski, the future director of the Zadoc Khan school, replaced him for that period at the Lévys’ school.

This portrait was taken in 1920, the year of his marriage to Fernande Hayem [6].

|

|

Portrait of Charles and Fernande’s birth certificate

|

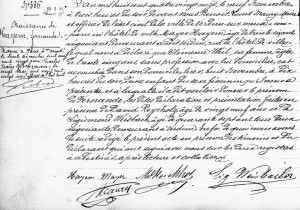

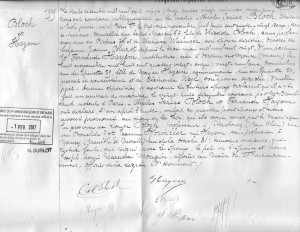

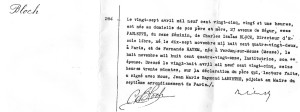

The December 31, 1920 issue of the magazine L’Univers Israélite informed the Jewish community that Charles and Fernande’s religious marriage ceremony would be celebrated on Sunday, January 2nd. On that date Fernande was living in the 17th district of Paris near the Porte Saint-Ouen and Charles resided in the 4th district close to the church of Saint-Merry. The civic marriage, whose certificate is shown on the next page, took place on December 30, 1920 |

|

|

The marriage produced two daughters,

Madeleine in 1921 and Paulette in 1925

|

In 1921, the year of Madeleine’s birth, the couple moved to n° 67 rue Saint-Martin in the 10th district. Jeanne Hayem, Armand Horviller’s wife, has furnished this information. When Paulette was born in 1925 Charles and Fernande lived at n°27 avenue de Ségur on the premises of the Zadoc Kahn School [7], which was being run by Alice and Nathan Schentowski.

As is recalled by Raphaël Elmaleh [8], the inhabitants of 27 avenue de Ségur were like a veritable family:

“The school was ‘home’ for the teachers. Germaine Bloch, Charles’s wife, Benoît Lévy’s assistant at the Lucien de Hirsch school, Mlle Birnbaum and Paul Hanneau, like many of these teachers, were from Alsace. [9]

As for Charles, he remained solely with the Lucien de Hirsch school, which over the years expanded considerably. Just before the Second World War it counted nearly 450 pupils. Most of them came from modest families in the 18th, 19th, and 20th districts of eastern Paris.

Raphaël Elmaleh [10] cites Lionel Rocheman’s report of Charles’s teaching post:

“M. Licheinstein taught Hebrew. There were also lessons in religion, taught mainly by Charles Bloch.”

From 1935 to 1943 he took part in the management of the establishment with the Schentowskis, who while on vacation received on the evening of August 24, 1939 [11]:

“a telegram from the chairman of the school board ordering me to return immediately to Paris, to gather as many of the pupils as possible, to buy bedding and to proceed as quickly as possible to Villers-sur-Mer, where the board had just acquired the property called ‘les Landiers’, which I had visited with the chairwoman’s architect [ ]. On August 29, 1939 I took everyone to the Saint-Lazare train station and left Paris, arriving at noon at the station in Villers with 103 children (56 girls and 47 boys).

On that same day I had entrusted 41 boys to M. Charles Bloch, who was to take them to another place, the château de Sainte-Croix, by government order; the children who were already there ‘on vacation’ were kept there and our group was taken to another summer camp at Colleville-sur-Mer. […]

Mme Schentowzki was in charge of one of the camps; our administrative staff consisted of M. Charles, Mlle Nathan, Mlle Leibovici.”

With the Debacle of July, 1940 everyone came back to the avenue Secrétan in Paris. Enrollment in the school plunged to fewer than 100 pupils in 1942.

“And yet it was still a functioning institution with its teachers, buildings, equipment, and showers, its canteen with its « hysterical » cook, Mme Semo, its ‘social and educational assistants’, Mme Bazy-Lesnovsky and Madeleine Bloch, the latter with the heavy burden in those times of scarcity of overseeing the canteen.” [12]

The school was to become the administrative “Secrétan Center” for the UGIF (General Union of the Israelites of France) [13], service 49 of the 4th group…It housed children and adolescents whose parents had been or were soon to be deported…. For the person in charge one of the main preoccupations was to feed all those living at n° 70 [14]:

Under Madame Bloch, the canteen functioned normally. The children were served around 400 meals a week.

Between 1942 and 1944 the children came and went as affected by events….Raphaël Elmaleh goes on: [15]

“…the teachers were at their posts: Madame Leibovoci (1st grade), Madame Doukhan (2nd grade), and Madame Nathan (3rd grade)….as well as Charles Bloch, and Monsieur Leibovici, the new director.”

Charles Bloch worked at the school to which he had contributed so much right up to his last breath. He died a natural death on February 24, 1943. The death certificate specifies that he was living at the school. Fernande and their daughters attended his burial in the Jewish sector of the Bagneux cemetery in Paris [16].

Alice and Nathan Schentowski were arrested in August, 1943 [17].

| Monsieur Nathan SCHENTOWSKI, born in Paris on March 20, 1884. Deported to Auschwitz in convoy n° 59 from Drancy on September 2, 1943. Profession: teacher. Died in 1943. Madame Alice SCHENTOWSKI, born in Paris on August 13, 1886, deported to Auschwitz in convoy n° 59 on September 2, 1943. |

Raphaël Elmaleh specifies that before this dramatic event Nathan told a former student [18]:

“Should I not come back, tell those who knew me that my last thoughts were for my pupils.”

It was in this religious community spirit that Madeleine and Paulette were brought up. The two sisters attended the Lamartine high school. Upon graduation Madeleine decided to become…. a social worker. In that capacity she was assigned to the UGIF’s center located at n° 21 rue des Tournelles in Paris. Her assignment covered Paris’s 3rd district. At the time she lived on the avenue Secrétan [19].

“Paulette, just before her father’s death, had graduated from high school. Fernande continued to take care of the girls, playing an important role in the school, first as a teacher, then as an acountant([20]).”

|

|

Paulette and Madeleine around 1935

The news from Nancy was alarming: Fernande’s sister Jeanne and her husband, Armand Horviller, were arrested and deported in convoy n° 71. Here is the content of their respective data sheets as published by the Mémorial de la Shoah.

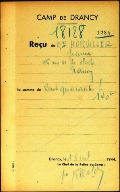

| HORVILLER Jeanne. Resident at n° 46 rue de la Hache in NANCY Interned at Drancy with the I.D. number 18128. Arrived on April 1, 1944. Attributed number 1284 in field research notebook n° 168. She was born on May 5, 1886 in Verdun. Deported to Auschwitz in convoy n° 71 from Drancy on April 13, 1944. Unemployed. |

|

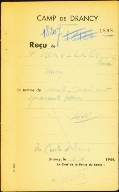

| HORVILLER Armand. Resident at n° 46 rue de la Hache in NANCY Interned at Drancy under I.D. n° 18127. Arrived on April 1, 1944. Attributed number 1418 in field research notebook n° 170. He was born on January 31, 1879 in NOMENY. Deported to Auschwitz on April 13, 1944 in convoy n° 71 from Drancy. Profession: merchant/grocer. |

|

Less than 18 months after Charles’s death, the unspeakable struck the school — the roundup of July 24, 1944. Raphaël Elmaleh [21] informs us that in 1953 it was decided to commemorate the deportation of the 107 children. In order to collect as much information as possible a questionnaire was sent to contemporary witnesses of the event:

“The witnesses solicited are essentially personnel at the school that year, teachers for the most part: Mmes Leibovici, Klein, Altschuler, Sommer, Kahn, Doukhan, and Madeleine Bloch, one of the rare survivors of the convoy. Neither her mother, the wife of Charles Bloch, who had for a time been assistant principal of the school, nor her sister were to survive the ordeal. Other recipients of the questionnaire: Colonel Khan, Georges Edinger, and Madame Bazy-Lesnovsky, ex-nurse and social assistant. Here are three extracts from her response, provided less for the historical precision of the roundup at which she was not present, than for the feelings expessed and the memory welling up 10 years after the events:

‘I was not present at the arrests because I lived at my home. I was told that the children were not yet dressed, which means they took place very early. There were about 150 children. I cannot be positive of that, either, as I did not deal with the register since the children were not our pupils but had come to us after the bombing of the refuge on the rue des Saules. There were beds everywhere (a fact emphasized by R. Bazy-Lesnovsky), and the access to my infirmary was obstructed. The arrests were made by German soldiers who had come in army vehicles; they took the children and the others to Drancy. Besides the children there was Mlle Marie Zalmanski (teacher), Madame Charles Bloch (accountant and former teacher) and her two children, Madeleine et Paulette Bloch. Madeleine alone came back. She was in Czechoslovakia, separated from her mother and sister’.”

Madeleine was not in Czechoslovakia. She was in Poland, at Auschwitz. Less than 10 days later, on July 31, the last convoy of deportees, convoy 77, left from Drancy.

Serge Klarsfeld [22] reminds us that more than 1200 people were crammed into those lead-sealed cattle cars. He calls on the account given by one of the deportees, Ralph Feigelson, who in the publication of the Licra (the International League against Racism and Anti-Semitism) relates what my cousins, Fernande, Madeleine and Jeanne experienced:

|

“Already camps could be seen, surrounded by walls, by wire — a cage in the middle of a great desert of terror and latent revolt — overlooked by watchtowers perched as if on stilts — guarding the flock. A strong wave of anguish grabs hold of us. The train halts. We have arrived. Night falls, complicit, casting a veil over the countryside. Several hours of terrible waiting. Suddenly shouts, hoarse orders, the doors are opened. Convicts run along the train. Some SS. People are being clubbed right and left. Blows on the arms, blows on the body, nothing but blows and more blows. No one has time to think. The night is torn by screams, gunfire. We are parked in rows of five in a corner of the arrival platform, blinded by floodlights. We are moved forward, then back, then forward again, like calves at a cattle market. An SS non-com pulls some off to the left, others to the right, a nonchalant gesture that sends the former to their death and reserves the latter to suffer. On the right are those he judges ‘fit for work’, that is sufficiently robust to be able to bear up under exhausting labor, deprivation and violence for a certain time. To the other side he pushes the sick, the children — three hundred kids from 6 to 12 years old whose only crime was being Jewish, to join their parents in the smoke of the crematorium furnaces. We look on and, our eyes wide with horror, take in scenes that the cruelest and most perverse mind could hardly conceive: ‘Look’ says an SS to his accomplice, pointing to a little child who has got out of line. Taking him by the feet, he throws him up in the air, while the other one shoots at this living target, laughing sadistically”. |

Fernande and Paulette were murdered upon their arrival in Poland. The text of the Decree of November 26, 2008 authorizing the mention “Died in deportation” on death records [23] is unambiguous:

| Bloch, born Hayem (Fernande) on November 8, 1891 in Verdun (Meuse), died on August 5, 1944 at Auschwitz (Poland) and not on July 31, 1944 at Drancy (Seine). |

| Bloch (Paulette), born on April 27, 1925 in Paris (7th district) (Seine), died on August 5, 1944 at Auschwitz (Poland) and not on July 31, 1944 at Drancy (Seine). |

My father recently recollected the family get-togethers in Nancy at n° 46 rue de la Hache, in the apartment located above the shoe store run by the ‘little uncle’ [24] , who, wearing his cap and accompanied by his wife Jeanne, would pick up ‘the Parisians’ (Charles, Fernande, Madeleine and Paulette) at the train station. The Lehmans — Berthe, Robert (my grandfather) and their five boys, Lucien, André, Georges, Paul and Pierre — were part of the party.

Nazi barbarity put an end to this simple happiness: Robert and Lucien were murdered at Auschwitz in 1942. Jeanne, Armand, Paul and Pierre followed in 1944.

Berthe and André escaped the holocaust…. Georges and Madeleine came back.

Life went on…. On July 1, 1946 my parents married at the town hall of Paris’s 10th district. Among the photos taken on that occasion are found my uncle Georges arm in arm with Madeleine.

|

At the beginning of the 1950’s a new team of teachers under the direction of Bernard and Marianne Picard took over the school. Madeleine was still welcome on the avenue Secrétan. That is where I met her for the first time. She continued to work there as a social assistant, dealing with the children whose parents did not return.

On March 28, 1954 a first memorial plaque was placed on the entrance of the school. Raphaël Elmaleh relates [25] that on that occasion Alain de Rothschild, in his role as president of the Paris consistory, was anxious to recall that:

“… It will soon be ten years that 107 little Jewish children and their teachers were deported from this school to Germany, never to come back. A single teacher survived by a miracle — Mademoiselle Bloch, who is with us here today and to whom I wish to express all the affection and respect we have for her with a thought for all the moral and physical suffering she has had to endure. It is she who has described for us the grim procession of these little children – including a little girl with a broken leg carried on a wooden plank — their convoy in the middle of the night to Drancy and the five-day journey, 120 jammed into a cattle car, in the dark, without air, without room, in filth and dying of thirst, and sent directly to the gas chambers or the crematorium furnaces on arrival. As an ultimate horror she watched as her mother, Madame Charles Bloch, dedicated wife and the school’s much missed assistant principal, was taken away to her death for having tried to console one of the little ones who was crying. Alas, the fate of the children of our school was not an isolated case. During that same night of July 24th, 350 Jewish children lodged in other centers suffered the same fate.”

She never married. She dedicated all her energy to spreading knowledge of the Shoah. In March, 1958 she was still at the school, where she gave out the Charles Bloch Prize, awarded “in memory of her parents, the former directors of our schools”. On June 18, 1972 and March 25, 1981 Madeleine filled out records pertaining to her mother’s identity. As she traveled around France, from school to school, from memorial ceremony to commemoration date, missing no religious feast day, she devoted herself to her Jewishness and held firmly to her simple Mitsva:

“Testify, testify again, so that it can never happen again.”

In an article on the Aryanization of education, the guide Trudaine Rochechouart [26], published by the city of Paris, restates:

“From 1942 to 1944 many pupils in the 9th district were arrested by the Vichy government and deported because they were Jewish. Lamartine High School saw 32 of its students, aged 12 to 19, and 12 of its former students perish in the death camps. Only Madeleine Bloch was to come back from there. A marble plaque put up in 2003 in the presence of Simone Veil honors their names.”

The name of Madeleine’s sister Paulette figures on this list.

Madeleine died in Chalon-sur-Saône on June 26, 2003. She was buried on the 30th in the Bagneux cemetery [27]. She rests there with her grandfather, Hayem Mayer, and her father, beside Chief Rabbi Jacob Kaplan and Lucien Rachet, the founder of the Licra.

[1] ) At the end of this document on page 22 a simplified family tree makes these family links clear.

[2] ) the list of the children is found on the last page.

[3] ) Par le souffle des enfants.: Livre d’or de l’École Lucien de Hirsch : 90 ans d’éducation juive en France, page 1.

[4] )Of these 107 children, 71 studied at the school.

[5] ) Raphaël Elmaleh, « Une histoire de l’éducation juive moderne en France », édition Biblieurope, page 174.

[6] ) document MJP8_42 of the Mémorial de la Shoah.

[7]) The school on the avenue de Ségur, opened in 1887, was first called the Schneider school, after the name of its director, Joseph Schneider. At his death in 1910 it took the name Zadoc-Hahn, and then was closed in 1935. It was from this date that Alice and Nathan Schentowski undertook the management of the Lucien de Hirsch school.

[8] ) opus cité, page 175.

[9] ) in various documents Fernande’s first name is given as Germaine. It is a preferred name she chose to go by, current practice at the time.

[10] ) opus cité page 176.

[11] ) opus cité page 178 et 180.

[12] ) opus cité page 183.

[13] ) Union générale des israélites de France. The French law of November 29, 1942 instituted on German demand under the General Commissioner for Jewish Questions a General Union of the Israelites of France. Its purpose was to provide the Jews with representation to public authorities. The image of the UGIF is considerably more questionable than it was 30 years ago. The organization has been reproached for failing to evacuate its children’s refuge centers before the July 1944 roundups.

[14] ) opus cité page 187.

[15] ) opus cité page 187.

[16] ) 31th division, 7th row, 31st grave.

[17] ) records of the Mémorial de la Shoah.

[18] ) opus cité page 186.

[19] ) Text based on information collected from the Mémorial de la Shoah.

[21] ) opus cité page 308 et suivante.

[22] ) «Par le souffle des enfants », page 10.

[23] ) JORF n°0009 du 11 janvier 2009, page 665.

[24] ) Armand Horviller .

[25] ) « Une histoire de l’éducation juive moderne en France page 314-315.

[26] ) disponible à l’adresse : http://actionbarbes.blogspirit.com/files/Guide_trudaine_rochechouart_complet_v1_2.pdf

[27] ) 31éme division, 7ème ligne, 31ème tombe.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Aujourd hui le 24 juillet j au fait une recherche avec la mention 24 juillet lucien de hirsh ou mon père caché par l ugif secretan alors qu il avait 15 ans a été déporté et pensait être le seul enfant rescapé. Merci pour votre témoignage familial