Isaac CHOUKROUN (1896-1944)

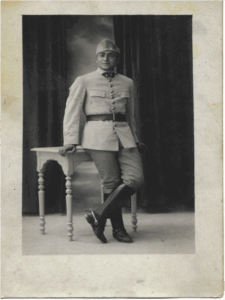

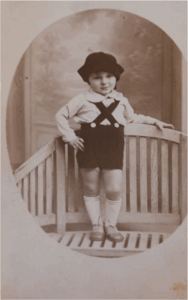

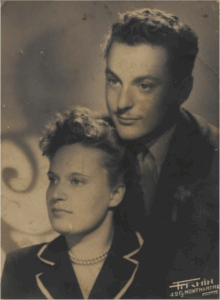

Photo of Isaac taken sometime before 1930

© Richard Cartozo’s personal collection

I. Isaac’s life before the war

His family

The meaning of the family name Choukroun is derived from the Arabic word “ashqar”, which means blond and red-haired.

Isaac was born at 3:30 a.m. on December 11, 1896, on rue d’Alger in Blida, which is known as “the city of roses”, in Algeria.

His father, Moïse, a street peddler, was 36 years old when Isaac was born, while his mother, Sultana (Sadia Chaïa), was 23 and did not go out to work.

Their marriage certificate provides some additional information:

Isaac’s father was born in 1860 in Kelaia, Morocco. His parents were Isaac Choukroun, who died in Morocco in 1869, and Semah Choukroun, who died in Jerusalem (date unknown).

His wife Sultana was born on June 2, 1873 also in Blida. Her parents were Sadia Chaïa, who worked in an auction house and died in Blida on October 8, 1892, and Luna Bent Jacob Dahan, who was a “housewife”.

Isaac Choukroun’s birth certificate ©ANOM

Moïse and Sultana were married on January 26, 1893 in Blida. They went on to have two children: Félicie, who was born on October 7, 1894, and then Isaac, two years later. They were a Jewish family, born French citizens under the “Crémieux decree” of October 24, 1870 which entitled Algerian Jews to French citizenship.

Isaac’s arrival in France and his life between the wars

Richard Cartozo told us how and why Isaac’s family emigrated to France.

From 1894 to 1906, French public opinion was split over the Dreyfus affair, and anti-Semitism was on the rise both in mainland France and in the French colonies. A wave of violence swept through French Algeria. In May 1897, anti-Dreyfus and anti-Semitic protests raged through Blida. Demonstrators took to the streets with a banner reading “Death to the Jews!”. Isaac’s uncle, Sultana Sadia Chaïa’s brother, Joseph Jacob Chaïa, who was a shoemaker, strode out of his workshop and slit the throat of the man holding the banner with a steel wire the he was using to cut leather. He did not kill the man, but as a result of the attack, Joseph had to flee and hide in the mountains for several months, with the help of family and friends, to avoid being arrested. This prompted Isaac’s family, including Moïse, Sultana, Isaac, Félicie and Sultana’s mother Luna, to flee Algeria by boat to Marseille, a port city on the south coast of France. Isaac was therefore just a child when he arrived in France.

We found Moïse Choukroun’s death certificate in the Marseille municipal archives. It states that he died on January 16, 1908, in rue Rameau, Marseille, at the age of 47. Isaac therefore lost his father when he was just 12 years old.

Sultana, who was left a widow, then married Moïse Haïm Cartozo in a Jewish ceremony. They had two children: Sarah Sadia Chaïa, who was born on December 7, 1909 and David Gaston Cartozo, born on January 27, 1912. Richard Cartozo, who helped us with this biography, is David’s son.

Under the French Civil Code of 1804, Jewish people, as well as Catholics and Protestants, had to get legally married in their local town hall first, and then, if they wanted to, get married in a religious ceremony afterwards. For Jews, this meant getting married in synagogue or by a rabbi. Sultana and Moses, however, did it the other way round. In 1915, Moïse, a class of 1897 soldier, was called up to the front in the Marne department of France. He was a driver-gunner in the 38th artillery regiment. Sultana and Moïse were married by proxy on June 8, 1915 in Marseille. They did this in order to provide some security for Sultana and legalize their marriage status. By getting married, Moïse officially acknowledged that he was the father of the children, thus making them legitimate. Their address at the time was on rue Haxo in the Opéra quarter of Marseille, which was home to a significant Jewish community, in particular in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Many Jewish families, often from wealthy backgrounds, lived in this centrally located, bustling area, close to the main synagogue on rue Breteuil and to La Canebière.

As for Isaac, according to the military archives held by the ANOM (Archives Nationales de l’Outre Mer, or French National Overseas Archives), he was in the class of 1916 and his military service number was 425. He was not called up, however, and the review board for the class of 1917 then struck him off the list because he was the son of a foreigner (his father was Moroccan).

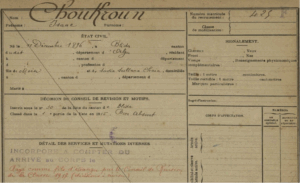

Isaac’s military service record © ANOM

Isaac in his army uniform, © Richard Cartozo’s personal collection

However, we do have a photograph of him in army uniform taken in a studio, even though he never went to war. It dates from 1925. According to Richard Cartozo, Isaac was something of a dandy, and always dressed smartly.

On March 6, 1920, Isaac’s sister Félicie married Adolphe Bentata, a customs clerk who was born in Oran, Algeria. According to Richard Cartozo, he was an opera singer, a tenor. In 1955, he officially changed his stage name to Adolphe Richard. This is why Félicie, who was also known as Alice, used the surname Richard.

When he was 30 years old, Isaac married Violette Esther Tikozinski at 11:20 a.m. on March 17, 1926, in the 10th district of Paris.

Isaac and Violette’s marriage certificate, dated 1926 © Paris city archives

Violette was born in Lille, in the Nord department of France, on March 6, 1905. Before she married, she lived in Paris with her parents: Edouard Tikozinski, a merchant, and Mathilde, who used her husband’s surname. They were originally from Poland and were both Jewish. Violette had two sisters: Colette Rachel and Marcelle Léa.

Isaac and Violette’s wedding photo, and a photo of their son, Maurice, when he was 28 months old © Richard Cartozo’s personal collection

The couple went on to have a son, Maurice, who was born in Marseille on January 30, 1927.

Isaac became a sales representative and worked from home at 9 rue Richer in Paris. In around 1935, he moved back and forth between Paris and their apartment on rue d’Haxo in Marseille. The whole family then moved to Paris, where they stayed until the outbreak of war in September 1939. According to the archives, they fled south on May 20, 1940, as did many other people from the Paris area and the north of France, as the German army was advancing towards the city.

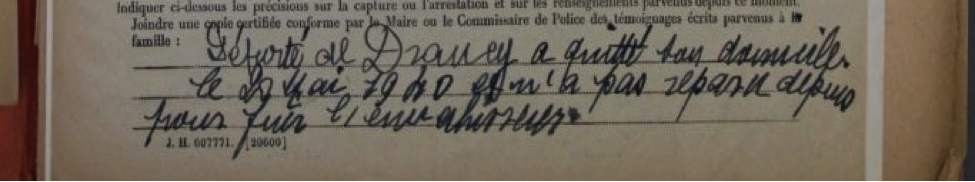

© Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21 P 436 448

Photo 1: From left to right: Violette, David, Maurice Choukroun, Sarah, Félicie “Alice” and Maurice Bentata in Apt, in the Vaucluse department, in 1928 © Richard Cartozo’s personal collection

Photo 2: Top: Isaac and Violette Choukroun, Middle: Sultana, Bottom: Maurice, their son, in 1932 © Richard Cartozo’s personal collection

II. The family sought refuge in Néris-les-Bains in 1940

On October 7, 1940, the Crémieux decree was repealed. This meant that the Algerian Jews who had acquired French nationality as a result of the decree, suddenly lost it[1].

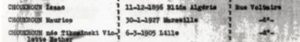

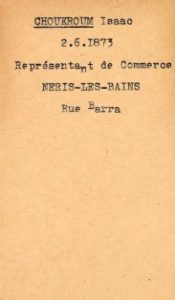

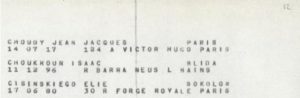

Records in the Allier departmental archives attest to Isaac being resident in Néris-les-Bains in the Allier department of the Auvergne region. Isaac is listed three times.

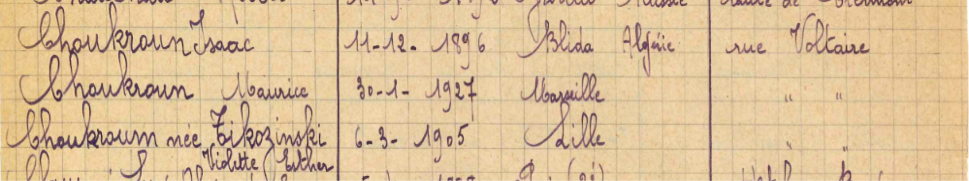

Census of the Jews in Néris-les-Bains on January 21, 1943

© Allier departmental archives, 996 W 2nde Guerre article 66

A 1943 list of “French Israelites [Jews] subject to the laws of December 9 and 11, 1942, residing in the municipality of Néris-les-Bains”, stamped by the police chief in Montluçon on January 21, 1943, includes the names of Isaac, his wife Violette and their son Maurice. Their address is listed as rue Voltaire in Néris-les-Bains. Violette’s parents were staying at the same address and her uncle, Maurice Tikozinski, was staying at the Splendid Hôtel. We counted a total of 129 Jews on this list.

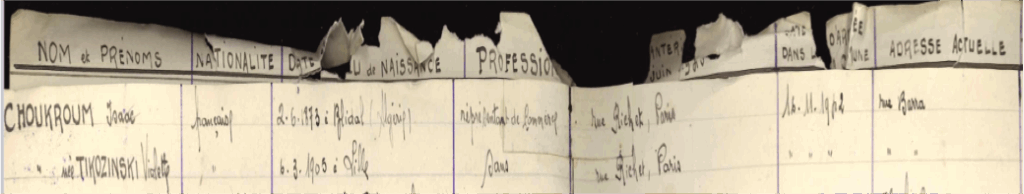

Census of Jews in Néris-les-Bains who were not subject to a removal order as of June 5, 1943 © Allier departmental archives, 996 W 2nde Guerre article 66

Also in 1943, on a list of Jews not subject to a removal order who were living in the Montluçon electoral division, stamped by the central commissioner in Montluçon on June 5 and then by the Allier prefecture on June 9, Isaac and Violette’s names are still included, along with their occupation and their previous address in Paris (rue Richer). By this time, they were living on rue Barra in Néris-les-Bains, and their arrival date is listed as November 16, 1942. However, neither their son Maurice, nor Violette’s parents and uncle are on this list. In fact, there are only 37 Jews in total.

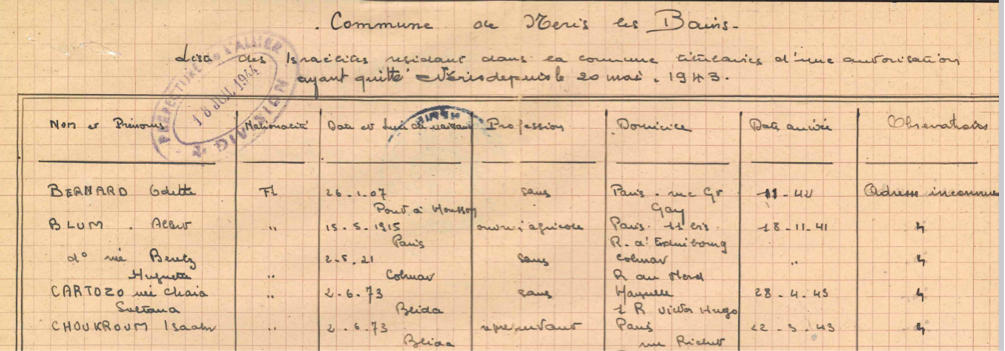

List of Jews who had left Néris-les-Bains since May 20, 1943

(document dated July 13, 1944)

© Allier departmental archives, 996 W 2nde Guerre article 66

In 1944, Sultana Cartozo née Chaia and Isaac Choukroum were included on a “list of Jews with authorization to live in the municipality who have left Néris since May 20, 1943”, drawn up by the mayor of Néris-les-Bains on July 13 and stamped by the Allier prefecture on July 18. Their address was listed as 1, rue Victor-Hugo in Marseille.

We found two first-hand accounts of what life was like in Néris-les-Bains at the time. The first was a book entitled Quand vient le souvenir (When Memory Comes), by historian Saul Friedlander, who was born in Prague in 1932 and also lived in Néris-les-Bains between 1940 and 1942. He took refuge there with his parents, and reflects on that period of his life: “If I had to choose a way to define the town, I’d venture to say that Néris is a smaller version of Vichy – which is hardly very precise – or, in the case of the period I am talking about, a smaller version of Vichy, minus the government but plus the Jews (…) As a result of the defeat and the exodus, the hotels and guesthouses of Néris-les-Bains were filled with a host of involuntary spa-goers, some of whom were regulars. Almost all of them, as I just mentioned, were Jewish”.

There were relatively few Jews in the Allier department before the war, but then when the war began, many of them sought refuge in Néris-les-Bains, which offered a number of advantages for refugee families, as it was a small spa town with plenty of hotels and furnished apartments. It was a long way from the main roads and in the “Free” Zone in the southern part of France, which was not occupied by the Germans. The census of Jews, carried out in 1941[2], listed a total of 3,669 Jewish people in Allier, of whom 2,894 were French and 775 were foreign. In the Montluçon administrative district, Néris-les-Bains was home to the largest number of Jews, followed by Montluçon itself, then Villebret and Commentry. In all, 501 Jews were recorded as living in the Montluçon district. Jews were not required to wear the star in the southern zone. This gave them a sense of security and made it easier for them to find housing, food and other supplies and to trade among themselves, since they were not allowed to work. In fact, the first decree on the “Status of the Jews”, enacted on October 3, 1940, banned Jews from working in a wide range of occupations. It was also what prompted some of them to go into hiding.

The second account we drew on is the book Ces excellents Français, une famille juive sous l’Occupation (These excellent Frenchmen*, a Jewish family under the Occupation) by lawyer Anne Wachsmann, published in 2020. It is based on some 100 postcards exchanged during the Second World War between her grandfather, her father (who was a child at the time) and other relatives who lived in Néris-les-Bains during the war. The author describes how the local population complained about the Jews, who were far too numerous for their liking, taking refuge in their town. The Jews were also accused of buying large quantities of groceries at any price due to their supposed wealth. Times were hard, and requisitioning had a serious impact on people’s day-to-day lives.

*translator’s note: this is a reference to a well-known wartime song, Ça fait d’excellents Français, by Maurice Chevalier.

As Isaac was no longer allowed to work, he had no income. He and his wife had to sell the family jewelry, silk stockings and the like on the black market in order to survive. The proceeds enabled them to buy food and save money, as food was very expensive at the time.

Isaac’s “French Jew” census card © Allier departmental archives, 996 W 2nde Guerre article 60

On August 26, 1942, just over a month after the Vel d’Hiv’ roundup in Paris, and three days after the pastoral letter from Monsignor Saliège, the Archbishop of Toulouse, and the reactions of other French Catholic and Protestant church dignitaries who opposed the Vichy government’s active collaboration with the Germans in arresting Jews, the French police carried out a major roundup of stateless Jews in the Free Zone. They targeted 18 municipalities in the Allier department and arrested 170 people, over 140 of whom were deported to Auschwitz. German troops took over Néris-les-Bains from May to July 1944, which proved especially tragic for Isaac. A total of 29 Jews living in the town were arrested during this period.

III. Arrest and deportation

According to the archives, Isaac was arrested on June 7, 1944 during a Gestapo round-up. However, Richard Cartozo gave us another version of events, as relayed by Isaac’s granddaughter.

Isaac is said to have received a letter, addressed to his son Maurice, summoning him to go to work for the STO (Service du Travail Obligatoire, or Compulsory Labor Service), or more specifically, for a GTE (Groupement de travailleurs étrangers, or Foreign Workers Group) elsewhere in France. Maurice, however, was not at home: he had joined a local Resistance group and was hiding out somewhere nearby. Isaac, in an attempt to keep him safe and to let him know that the Gestapo were on his trail, went to their hideout, only to find that the Gestapo had got there first. Someone had already warned the resistance fighters, who had fled the area. The Gestapo therefore arrested Isaac as soon as he arrived on the scene and stole everything he had on him, which included what was left of the family jewelry, their only means of survival.

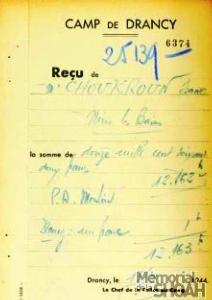

After Isaac was arrested, he was interned in Vichy, possibly on boulevard des États-Unis where the Gestapo had requisitioned 25 buildings, including the Hotel du Portugal, which they used as their headquarters. He was then sent to la Mal-Coiffée, a German military prison in Moulins. From there, he was transferred to Drancy, an internment and transit camp north of Paris, where Jews were sent prior to being deported. When he arrived there on July 15, 1944, he was assigned the serial number 25,139.

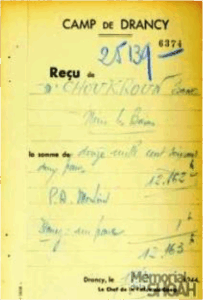

According to the Drancy search log, Isaac had the sum of 12,162 confiscated from him, as shown on the receipt below.

Drancy search log receipt, © Shoah Memorial, Paris

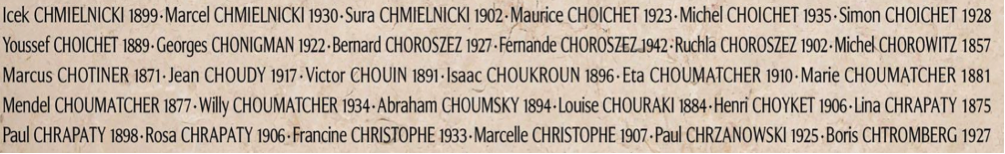

A fortnight later, on July 31, 1944, Isaac was taken by bus to the nearby Bobigny train station, as were 1305 other Jews who were about to be deported,. The youngest of them was Alain Blumberg, who was just 15 days old (he was born in Drancy) and the oldest was Benoît Levy, who was 87.

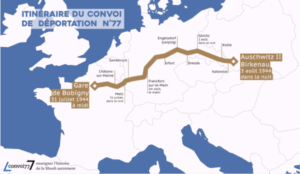

Isaac then climbed into a cattle car with hardly any drinking water. The journey lasted several days, in high summer, with no rest stops and very little food. The only sanitation was a bucket, that everyone had to use. This was the last major deportation convoy to Auschwitz Birkenau: Convoy 77.

The route taken by Convoy 77

© Convoy 77 website

When the train arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, during the night of August 3-4, 1944, the selection process was carried out immediately:

- Of the 1306 deportees, 836 were sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered, including all of the children.

- 291 men and 183 women were selected to enter the camp to carry out forced labor.

- In 1945, when the war came to an end, only 250 of them, 157 women and 93 men, were still alive.

We do not know exactly how or when Isaac died. He was 47 years old when he arrived, so might have been selected to enter the camp, but was he in good health and fit enough to work?

We know from Richard Cartozo that Isaac suffered from Parkinson’s disease. The journey must have taken its toll on him, so he was probably deemed to be unfit for hard work. If that was the case, the Nazis would have taken him straight to the gas chambers as soon as he arrived. It is also possible that he died on the train on the way there. Or maybe, as a man with no family with him, he was in the so-called “bachelors” car, from which some prisoners tried to escape, but failed. The 60 men who were either found out or were reported by someone were taken prisoner during the journey and then taken immediately, naked and in chains, to the gas chambers.

IV. In memory of Isaac and his family’s life after the war

After the war, Isaac was officially declared to have died on August 5, 1944, 5 days after he left Drancy camp: if there was no further news of the deportees, the French authorities deemed the youngest and oldest to have been taken to the gas chambers and killed soon after they arrived in Auschwitz. This is why many death certificates of so many people who were deported on Convoy 77 state that they died on August 5, 1944.

On September 27, 1947, Isaac’s wife Violette began the necessary procedure to have his civil status updated to that of “non-returned person”. The French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War issued a missing person’s certificate on October 14, 1948 (dossier number 63500).

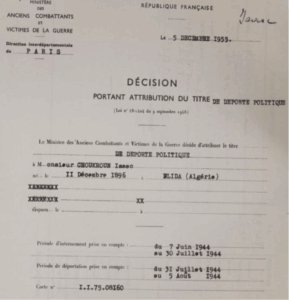

Five years later, in 1953, Violette applied for Isaac to be granted “political deportee” status, in recognition of the fact that he had been deported solely because he was Jewish. On December 5, 1955, when the file was complete and approved, the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War issued a Political Deportee card in Isaac’s name and sent it to his wife.

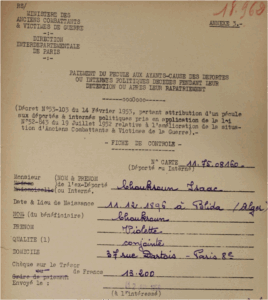

Decision to issue a Political Deportee card in Isaac’s name © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21 P 250 086

When Isaac was arrested, he was carrying his entire fortune with him, so his wife was left with nothing. Her parents and her sister Colette helped her out financially. When eventually the French state granted Isaac political deportee status, she received an indemnity payment of 13,200 francs (according to the 1953 decree granting deportees’ heirs a sum of money to ease their financial difficulties).

Moïse Haïm Cartozo, Isaac’s father-in-law, who helped out the family financially during the war, was also rounded up in Marseille. On January 22, 1942, he was deported on Convoy 52 from Drancy to Sobibor where he died at the age of 66.

Confirmation of indemnity payment for dependents of political deportees or internees who died in custody © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier 21 P 436 448

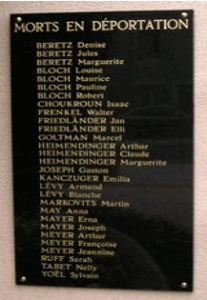

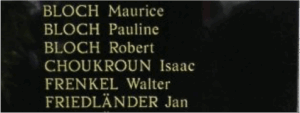

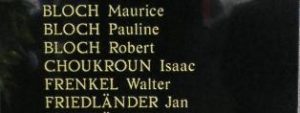

On May 8, 2008, a commemorative plaque was unveiled on the Néris-les-Bains war memorial in memory of the 29 Jews who took refuge in the town and were deported. Isaac Choukroun’s name is also inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

The commemorative plaque in Néris-Les-Bains

The Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

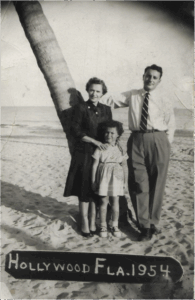

As for Isaac’s son Maurice, he married Jacqueline Rosenberg in Paris in 1946. As both of their fathers had been deported and died, they set off to begin a new life in the United States. They initially lived in Boston, Massachusetts and then moved to Hollywood, Florida, where they had a daughter named Nancy in 1949. They later moved to Santa Monica, Florida, before returning to the South of France. Maurice died in Montpellier in 2007. At the time of writing, Jacqueline lives with her daughter Nancy in Perpignan, in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France.

Isaac’s wife, Violette, died in Nice, in the Alpes-Maritimes department of France in 1991, at the age of 86.

Photo of Maurice and Jacqueline Choukroun (photo 1) and them with their daughter Nancy (photo 2), © Richard Cartozo’s personal collection

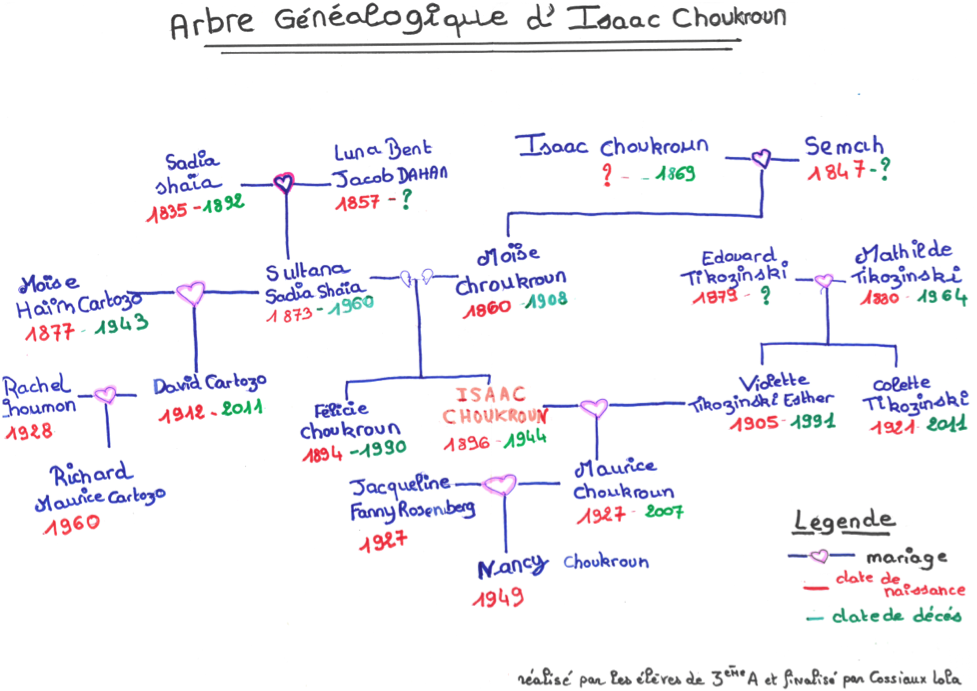

Isaac Choukroun’s family tree

Thanks

We were able to contact Richard Cartozo via social networks and a genealogy website. He very kindly helped us to retrace Isaac and his family’s lives during a series of telephone conversations.

We would like to thank him for all his help and for providing us with so many details and photos.

We drew on documentation from the Shoah Memorial in Paris and the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy, the French National Overseas Archives, the Allier departmental archives and Richard Cartozo’s personal collection. We also referred to the biography on the Allier AFMD website and a previous version of the biography on the Convoy 77 website. We used some of documentation to illustrate the biography, and included throughout the story.

Notes & references

[1] This measure was not abolished until October 21, 1943, almost a year after the Allied landing in Algeria (November 8, 1942) and the re-establishment of a free French territory.

[2] Although the Germans did not occupy the area below the demarcation line (except for the coast) until November 11, 1942, the Vichy government ordered a census of Jews there under the terms of a decree passed on June 2, 1941.

——————————————————————————————————————–

Excerpt from the biography produced by the AFMD (Amis de la Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Déportation de l’Allier, Friends of the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation of Allier):

——————————————————

لقراءة هذه السيرة بالعربية يرجى النقر هنا

—————————————————–

Isaac Choukroun was born on December 11, 1896 in Blida (Algérie). He was the son of Moïse and Sadia Guetanu.

He married Violette née Tikozinski on March 17, 1926 in Paris (10th district) and they had one son, Maurice, born in Marseille.

A sales living on rue Richet in Paris (9th district) he sought refuge in Néris-les-Bains on November 16, 1942, firstly on rue Voltaire, then on rue Barra […]

——————————————————————————————————————–

Il épouse Violette née TIKOZINSKI le 17 mars 1926 à Paris (10ème) et ils ont un fils, Maurice, né à Marseille.

Commerçant /représentant de commerce domicilié rue Richet à Paris (9ème) il se réfugie à Néris-les-Bains le 16 novembre 1942 d’abord rue Voltaire, puis rue Barra […]

إسحاق شوكرون

1896- 1944/ الولادة : بليـــــدة / الاعتقال : مولانس / الإقامة : بليدة، نيريس-لي-بان، باريس

هذا المقتطف مقتبس من سيرة أنجزتها جمعية “أصدقاء مؤسسة من أجل ذاكرة الترحيل بألــيـي”

ازداد إسحاق شوكرون يوم 11 دجنبر 1896 في مدينة بليدة بالجزائر. فهو ابن موسى وسعدية كتانو. تزوج بفيوليت تيكوزينسكي يوم 17 مارس 1926 بالمقاطعة العاشرة بباريس. وازداد ابنهما، موريس، بمارسيليا يوم 30 يناير 1927.

كان إسحاق يشتغل تاجرا وممثلا تجاريا يقطن بزنقة ريشي في المقاطعة التاسعة بباريس، ولجأ إلى مدينة نيريس-لي-بان يوم 16 نونبر 1942 أولا بزنقة فولتير ثم بزنقة بارا.

وتحتفظ أرشيفات إقليم الأليـي ببطاقة برتقالية تؤكد أن إسحاق مقيد من طرف الدولة الفرنسية سنة 1943 كيهودي فرنسي.

وقد ألقي القبض على إسحاق في حملة حصلت بنيريس-لي-بان يوم سابع يونيو 1944، سجن على إثرها بفيشي، ثم بمال-كوافي، في السجن العسكري الألماني في مولانس (03). ونقل بعد ذلك، في 15 يوليوز 1944، إلى معسكر درانسي تحت رقم 25139.

ورحل يوم 31 يوليوز 1944 نحو أوشفيتز عبر القافلة 77.

وقد كتب سيرج كلارسفيلد، في ميموريال ترحيل يهود فرنسا، بخصوص القافلة 77 : “إن عدد المرحلين بلغ 1.300 مرحلا. والقافلة 77 (…) دفعت نحو غرف الغاز بأوشفيتز بأكثر من 300 طفل يبلغون أقل من 18 سنة. (…) 291 رجلا منهم تم انتقاؤهم بالأرقام من باء 3673 إلى باء 3963، ونفس الشيء بالنسبة للنساء 283 امرأة من الرقم ألف 16457 إلى ألف 16739. وكان هناك سنة 1945، 209 ناجيا من بينهم 141 امرأة”.

بعد وفاته، منح إسحاق شوكرون بطاقة “مرحل سياسي” تحت رقم 1.175.0816، بناء على قرار من وزارة قدماء المحاربين بتاريخ خامس دجنبر 1955. وكان قد توفي يوم الثالث غشت 1944 بأوشفيتز في بولونيا حسب ما جاء في الجريدة الرسمية عدد 190 بتاريخ 17 غشت 2012.

وقد ورد اسم إسحاق شوكرون في لوحة تذكارية علقت بنيرس-لي-بان خصصت لموتاها، وكتب عليها “متوفون في الترحيل”. هذه اللوحة أنجزت على إثر أبحاث “جمعية أصدقاء مؤسسة من أجل ذاكرة الترحيل بأليي”. وقد تم الكشف عنها يوم ثامن ماي 2008 من طرف السيد جان كلود دوبان، عمدة نيريس-لي-بان، والسيدة مود لورش، والسيدة كوليت بورغوانيون، نائبة رئيس فرع مونلوسون–كونتري، التابع للفدرالية الوطنية للمرحلين والمحتجزين المقاومين والوطنيين.

مع جزيل الشكر لبلدية نيريس-لي-بان على وفائها لذاكرة الترحيل.

Français

Français Polski

Polski