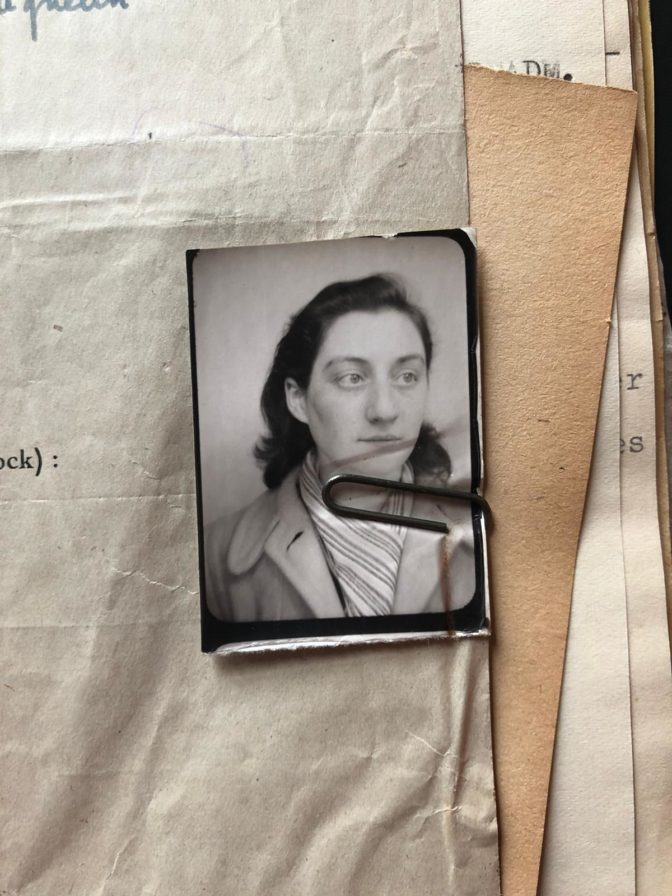

DENISE SCHNEER

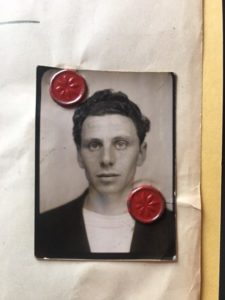

Identity photo of Denise Schneer from 1948-1952, Source: French Military Archives, Vincennes, ref. GR 16 P 540562.

Denise Schneer was born on July 15, 1926 in Perreux-sur-Marne, which is to the east of Paris in the Val de Marne department of France.

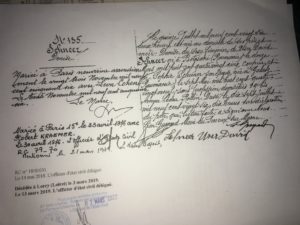

Denise Schneer’s birth certifcate (Perreux-sur-Marne town hall)

Denise was the youngest of three siblings born in Le Perreux-sur-Marne, including her older sister, Paulette Schneer, who was born on May 26, 1922 and died on January 17, 2006 in Villejuif, and her older brother, Maurice Schneer, born on March 18, 1925 and died on November 29, 2011 in Longjumeau.

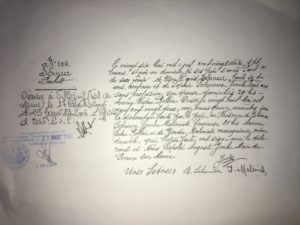

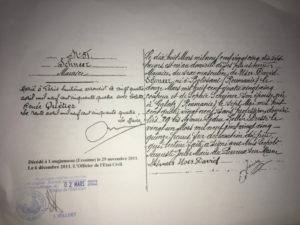

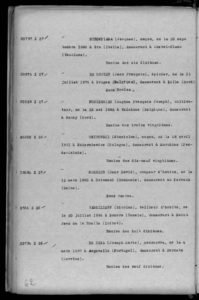

Birth certificates of Paulette Schneer (on the left) and Maurice Schneer (on the right) (Perreux-sur-Marne town hall)

Her parents, who were originally from Romania, moved to France in the late 1890s. His mother, Sophie Schneer, who was born Scheiner on May 7, 1889 in Galatz, Romania, was naturalized as a French citizen on May 7, 1896. Her father, User David Schneer, a tailor, was born on March 12, 1885 in Botosani, Romania, but did not become a French citizen until October 4, 1927:

Register of people naturalized as French citizens on December 26, 1896 (French Law gazette, Bulletin n°3065, Decree n°50350) Register of people naturalized as French citizens on October 4, 1927, p.62

Source of naturalization decrees

These applications for French citizenship were made in the context of a wave of migration from Eastern Europe. In effect, as a result of the anti-Semitic policy of Tsar Alexander III in 1881 (intensified by his successor Nicholas II) and the growing number of pogroms, many Jews fled the countries close to Russia and the “residence zone” called the Pale of Settlement. This was in the west of the Russian Empire and Jews were restricted to living there from 1791 to 1917. It included the principality of Moldavia, which is now the country of Moldavia and the Moldavian region of Romania (where the towns of Galatz and Botosani, from where Sophie Scheiner and User David Schneer came from, are located). As the persecution increased, many Jews fled this “residence zone” and emigrated to Western Europe (Catherine Gousseff, Les Juifs russes en France. Profil et évolution d’une collectivité, https://www.cairn.info/revue-archives-juives1-2001-2-page-4.htm et https://fr-academic.com/dic.nsf/frwiki/1759234).

The Schneer family lived at 29bis, avenue Ledru Rollin in Perreux, in the Val-de-Marne department of France.

Recent photo of the house where the Schneer family lived – Photo : D. Abassi

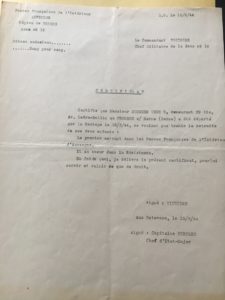

Denise’s father, User David Schneer, was arrested on March 18, 1944 for refusing to reveal “his children’s safe house”:

Deportation certificate of User David Schneer, dated 15/08/1944

(French Military Archives in Vincennes)

He was interned in Drancy camp:

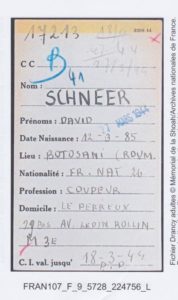

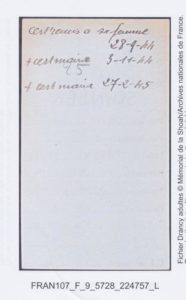

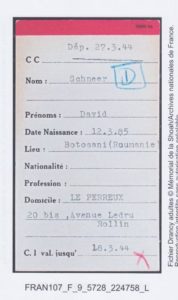

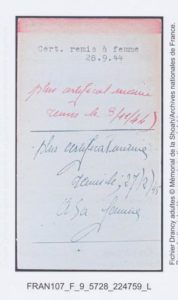

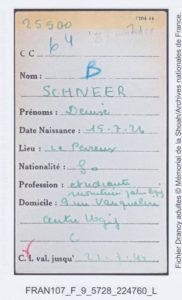

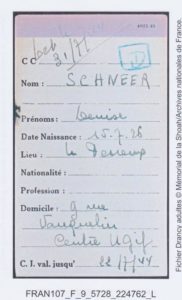

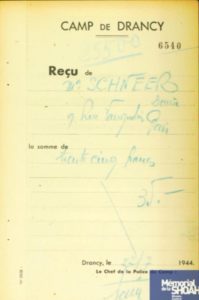

Drancy camp registration cards of David and Denise Schneer (French National Archives, ref. F/9/5728)

He was deported on March 27, 1944 on Convoy n°70 to Auschwitz-Birkenau and died in the Lublin-Maidanek concentration and killing center on April 1, 1944, probably as soon as he arrived there:

(Order dated March 3, 2000 pertaining to the addition of the words “Died during deportation” in the margins of death certificates and declarations of death:

His wife, Sophie, survived the war and died on June 19, 1956 in Bagneux.

Denise’s father arrested for refusing to give away his children’s hiding place?

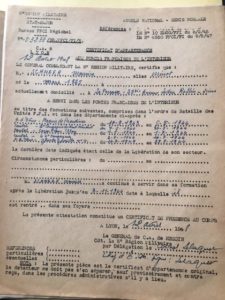

During the Second World War, Maurice Schneer, the eldest of the siblings, who worked as a furrier before the war, joined the Resistance. He became a corporal in the FFI (French Forces of the Interior) under the alias “Minot”. From September 1943 to August 1944, his clandestine activities took him to the Prondines Maquis (Resistance group) in the Puy de Dôme department, to the Mont-Mouchet Company in the Cantal department and to the 44th Company, as well as to guerrilla zone n°4 in the Puy de Dôme department. He continued to work with the Resistance until November 9.

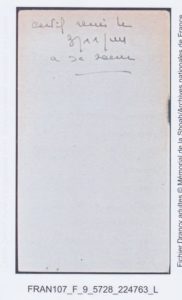

Photos of Maurice Schneer (ref. GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes)

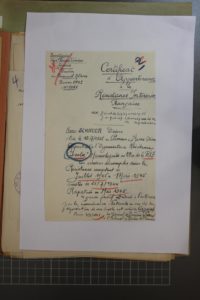

FFI membership certificate (ref. GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes)

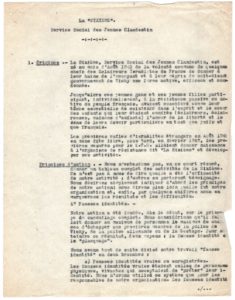

During the war, as a student, Denise Schneer was a member of the UGIF and the EIF.

The Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews was founded on November 29, 1941 by the Vichy government, on the orders of Nazi Germany. The purpose of the law creating the UGIF was to make the Jews in France more readily identifiable, to merge them into a single community and to put an end to their integration into French society. In return, Germany and the Vichy government agreed to allow the existence of a certain number of welfare organizations. The UGIF thus ensured that the Jews were “represented”: it was the only authorized point of contact with the Germans and the Vichy government. It also provided social services: it paid welfare benefits to households with little or no income and financed soup kitchens, hospices and the like. However, the creation of the UGIF was a departure from the republican and secular traditions that the Third Republic had put in place.

After the round-ups in the summer of 1942, the Service Social de la Jeunesse (Social Welfare Service for Young People) was founded. This organization opened children’s homes in and around Paris. There were children’s homes on rue Lamarck and rue Vauquelin, the ORT (Organization Reconstruction and Work) technical school on rue des Rosiers, and centers in Louveciennes, la Varenne, Montreuil and Neuilly. These homes were supervised by the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives (General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs) and the Gestapo.

The role of the UGIF provoked much controversy after the war. The organization was accused of collaboration during the Occupation. In the eyes of the resistance movements, the UGIF was seen as “the illusion of an agreement between the bandit and the victim”. Historians can only try to determine the degree of supposed participation of the UGIF leaders in an infernal scheme conceived by the Nazis and designed to gradually entangle their victims in the process of internment and then deportation of the Jews from France. Even now, a historiographical debate about this subject is still ongoing. (See: Jean Laloum, L’UGIF et ses maisons d’enfants : le centre de Montreuil-sous-Bois, https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-monde-juif-1984-4-page-153.html et M. Lafitte, Un engrenage fatal, Liana Levi, 2003)

Denise Schneer worked at the UGIF home n°.19, but she was arrested at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris.

Photos: M. Jalil

She was arrested during the round-up that took place at the home on rue Vauquelin on the night of July 21 – 22, 1944. The children’s home housed 33 Jewish girls, all of whom were arrested at the same time as Denise Schneer.

ref. GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

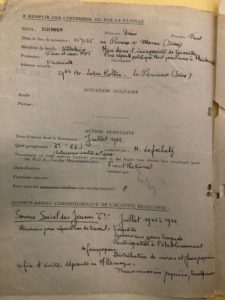

Denise Schneer’s activity as a Resistance fighter began in July 1942 as part of her involvement in the EIF, the Éclaireurs Israélites de France (Jewish Scouts in France). The EIF, which was founded in 1923, adopted an educational scouting approach with the aim of uniting all Jews. The mainstream Scouts of France refused to affiliate with the EIF because they considered it “too sectarian”. Like other Jewish organizations of the time, the organization was disbanded on November 29, 1941. After that, many former members of the EIF joined the Resistance and created their own units (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eclaireuses_et_Eclaireurs_israelites_de_France and https://www.eeif.org).

Among them was Emmanuel Lefschetz. Until then, he had been responsible for the development of the MJS, (Mouvement de la jeunesse sioniste, or Movement of Zionist Youth), which brought together the various Jewish youth movements in Paris. Following the Vel d’Hiv roundup on July 16 and 17, 1942, he called on young people to form a group called the “Sixth” within the EIF. This was an underground social service for young people which took care of children whose parents had been arrested. Within this structure, E. Lefschetz coordinated the production of false identity papers and other clandestine documents and sought out hiding places to shelter Jews who were wanted by the police and the Gestapo (http://www.ajpn.org/personne-Emmanuel-Lefschetz-3795.html).

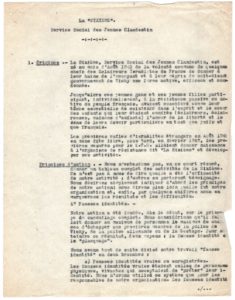

The roots of the “Sixth” – ref. CMXLIII/4/5/1, Shoah Memorial in Paris

The roots of the “Sixth” – ref. CMXLIII/4/5/1, Shoah Memorial in Paris

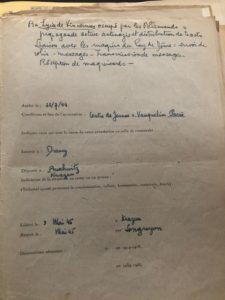

This was how Denise Schneer joined the “Sixth EIF” in July 1942. She remained a member of the group until she was arrested on July 22, 1944. Her involvement in the “Sixth EIF”, the social welfare arm of the “Jeunes clandestins” (young people in hiding), is proven by the information in the files that Denise Schneer compiled after the war in order to have herself recognized as having been a “political deportee”:

– Her Resistance code name was “Furet”, meaning “Ferret”.

Ref. GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

– Denise knew Emmanuel Lefschetz and other Resistance fighters by their code names:

Ref. GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

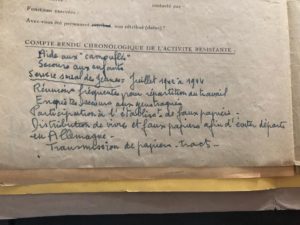

– She listed her covert activities:

Ref.GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

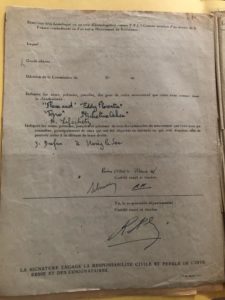

– She provided witness statements to prove that she had been involved in the Resistance movement.

Ref. 21 P 672 155 53633, DAVCC Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service), and ref. 21 P 672 155 53633, DAVCC, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit associaton

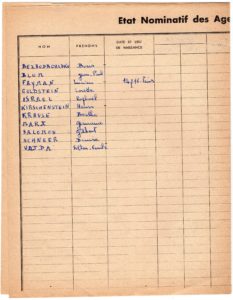

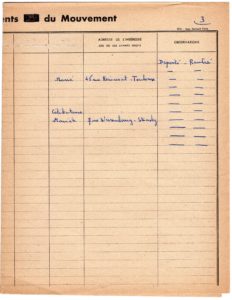

In 1947-1948, the EIF compiled a list of its agents and their status. Denise Schneer is listed as: “Deported-Returned”.

Ref. CMXLIII/4/5/6, Shoah Memorial in Paris, France

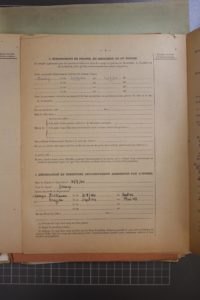

Denise Schneer was interned in Drancy camp on July 22, 1944:

Drancy camp registration forms for David and Denise Schneer (French National Archives, ref. F/9/5728)

For historians Renée Poznanski and Denis Peschanski, (in their book Drancy, un camp en France, published by Fayard-Ministère de la Défense, 2015), the Drancy internment camp was, from August 1941 to August 1944, a hub of anti-Semitic deportation policy in France. Designed by Marcel Lods and Eugène Beaudouin in the 1930s, it was an ideal place to prevent people from escaping. The U-shaped building is a cul-de-sac surrounded by barbed wire. The project was originally intended to provide housing, with large towers and a three-story U-shaped building. However, no buyers were found for the towers and the U-shaped building remained unfinished for some time. The Defense Department bought it to house police officers, who later became camp guards. Before it became an internment camp for Jews, it was a prisoner of war camp for non-commissioned officers and colonial soldiers.

From July 1943 until it was closed on August 18, 1944, Drancy was run by SS commander Aloïs Brunner.

Photograph of Aloïs Brunner in R.Poznanski and D.Peschanski’s, Drancy, un camp en France, Fayard-Ministère de la Défense, 2015

Photograph of Aloïs Brunner in R.Poznanski and D.Peschanski’s, Drancy, un camp en France, Fayard-Ministère de la Défense, 2015

Under his leadership, the daily life of the internees was marred by extreme violence: they performed forced labor and were beaten and even tortured. Meanwhile, the food, health and living conditions improved somewhat for the Jews with the help of UGIF food parcels and social services.

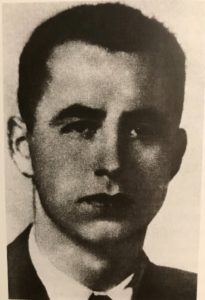

When she was admitted to the internment camp, Denise was searched and had to hand over the 35 francs (worth about 6 dollars today) that she had on her.

Drancy search log for Denise Schneer when she arrived at the camp, Shoah Memorial in Paris, France

The future deportees were placed in dormitories in blocks 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. They were moved regularly. As the residents moved towards Block 1, it meant that their departure date was drawing nearer, but they were not actually notified that they were going to be deported until the day before they left.

Model of Drancy internment camp, Shoah Memorial, Drancy, France – Photo: E. Esbri

The Cité de la Muette today, Photo E. Esbri

On the morning of July 31, Denise and 1,308 other deportees were loaded into the cattle cars of Convoy No. 77, which was to take them to Auschwitz. It was the last of the large convoys from the Drancy internment camp to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The travelling conditions were inhuman: 60 people were crammed into each 200 sq. ft wagon with just one bucket to relieve themselves. The heat was stifling. There was a small amount of bread but little or no water. It was not unusual for deportees to die along the way, which was a type of initial selection process. The convoy made a short stop on the second day, when “one prisoner per car was allowed to fetch some water from a water fountain”. (Régine Skorza-Jakubert, Fringale de vie contre usine à mort, Ed. Le Manuscrit- Fondation pour la mémoire de la Shoah, 2009, p.147)

Auschwitz-Birkenau

Beyond the chronology that Denise Schneer gave in the files she compiled after the war, we were unable to find any witness accounts or other records pertaining to her deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau and then to Kratzau. We have therefore used testimonies of other people who were deported on Convoy 77 to piece together what happened during this time: that of Yvette Dreyfus, available on the Convoy 77 website https://en.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/yvette-dreyfuss/ and the autobiographical accounts of Régine Skorza-Jakubert in Fringale de vie contre usine à mort, published by Le Manuscrit Eds – Fondation pour la mémoire de la Shoah, 2009 and of the Bloch sisters, Simone and Lison, in Les petites juives de Kratzau, published by Ampelos in 2021. The convoy arrived at the platform inside the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp during the night of August 3 to 4, 1944.

Ref.21 P 672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

When the train arrived, the “selection” was carried out. The SS separated the men from the women and then Dr. Mengele made an initial selection.

Photo from L’Album d’Auschwitz, Ed. Al Dante-Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, 2005

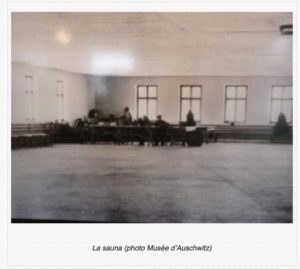

The women selected to be sent into the concentration camp were no older than 30 years of age. The others, who were considered either too young or too old to work, were put in trucks that took them to the gas chambers. Denise Schneer was in the first group. She and the other women were taken to the “sauna” where they were told to get undressed.

Source: Auschwitz museum, Poland

Some men came to collect their clothes while others with razors shaved their hair, armpits and pubic hair. Denise Schneer’s number, A16799, was tattooed on her forearm. They were then given some clothes to wear.

The women from Convoy 77 who had been selected to stay in the camp were then transferred to wooden barrack huts, where they found “three-level bunk beds. One bed for ten people on each level. Planks and nothing else.” (Régine Skorka-Jacubert, p.151) :

Photos: S. Brizard

The day after they were admitted to the camp, the women were woken up by the sound of a whistle blown by a Kapo (an acronym for Kamerad Polizei, who were also inmates, but generally given the task of supervising the deportees in their barracks and to work, either in the camp or outside). The women in the barracks had to attend a roll call, and then those from Convoy 77, who were not allowed any contact with the other women in the camp, were assigned to tasks that had no real purpose: Denise’s daily routine involved transporting stones and bricks from one place to another, as was the case for the other women from Convoy 77. The work was pointless, and its only purpose was to wear them out. Their day-to-day lives were also marred by the constant fear of the regular selections, which could result in their being sent to the gas chambers.

According to the files that Denise Schneer compiled after World War II, she remained in Auschwitz-Birkenau until September 1944, when she was transferred to the Union Werk (labor camp) in Kratzau, in the “Great Reich”:

Ref.21 P 672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

It is worth noting that both Yvette Dreyfus and Régine Skorka-Jacubert reported that they left Auschwitz-Birkenau for Kratzau on October 27, 1944. Might there have been several transfers of deportees from Convoy 77 to Kratzau between September and the end of October 1944??

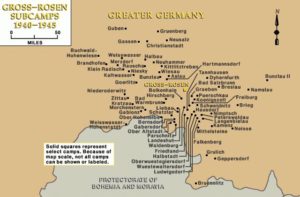

The Kratzau camp was a munitions factory and a subcamp of the Gross Rosen concentration camp:

Map of Gross Rosen subcamps, 1940 – 1945

Kratzau

Régine Skorka-Jacubert wrote that they were crammed into cattle cars, more than 100 per car, “without food, without water, and with no sanitation” (p.77). The journey lasted two days according to Régine Skorka-Jacubert: “It took us two days to travel three hundred kilometers (186 miles)” but three according to Yvette Dreyfus “This journey also lasted three days and three nights”.

The first morning after they arrived, they were assigned to various work stations (kitchen, factory, etc.). We do not know what work Denise Schneer was given, but most likely she worked in the weapons factory, as did the majority of the camp inmates, including Yvette Dreyfus: “I worked in an arms factory. I was a lathe operator and made pistol parts for the P36 model and also for rifles. Later on, I made nozzles, a kind of pipe, which was filled with powder and placed under the V1s and V2s.”

The Jews were not the only prisoners in the camp; there were also French people who had refused to become German citizens, Yugoslavs, Italian prisoners of war, etc. All of them worked there as laborers, but communication between the different groups was forbidden. However, they were not always supervised, particularly in the paint shop, where dangerous acetone fumes were released. As a result, out of sight of the German officers, groups of workers and Jewish prisoners sometimes helped each other out.

In Kratzau, there was no morning roll call and no regular “selections” as there had been in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The winter of 1944 was particularly harsh, however. The inmates had no shoes, were poorly dressed and underfed (they were given coffee and a piece of bread in the morning and soup in the evening). The barracks were unheated and there was only one blanket for to cover ten people. Sundays were different: there was no work, the prisoners were given 3 or 4 boiled potatoes, and there was a delousing session during which all of them, sitting in single file, searched for lice on the woman in front of her. (Simone and Lison Bloch, p.84).

At the end of April 1945, the prisoners in Kratzau realized that Hitler must have died when they saw the flags at half-mast. A wind of hope blew over the camp. A rumor went around that the Russian troops were coming closer and it was not long until the prisoners saw the Germans, both civilian and military, fleeing.

On May 8, 1945, the women heard that the war was over when some Italian prisoners threw them some loaves of bread. On May 9, when the prisoners got up, they were astonished to find the camp devoid of Germans and the SS. According to Yvette Dreyfus and the Cohen sisters, the camp was “liberated” by the Russians. However, according to Regine Skorka-Jacubert’s biography (https://en.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/skorka-regine/) it was liberated by Czech partisans. She recounts the moment when they arrived, when a motorcycle tore off the camp gate and a tank drove into the camp. The Russians then set up a sort of canteen. However, after this initial assistance, they were given no help at all. The deportees felt abandoned: “When I think of my liberation and the days that followed, the overriding feeling is one of immense abandonment. No one took care of us” Yvonne Dreyfus explained. There was no food, no one to guide them and no transport out of the camp. Most of them resolved to steal from the surrounding villages, which the Germans had abandoned and left deserted.

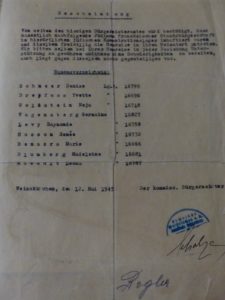

Yvette Dreyfus recounts that she “went to the Kratzau town hall” together with another woman and “obtained a pass from the mayor himself” for her and eight of her comrades, including Denise Schneer, to return to France:

The pass issued by the mayor of Kratzau. Source: Yvette Dreyfus private collection, https://en.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/yvette-dreyfuss/

When she returned to France, Denise was sent to a convalescent hospital, where she stayed from May 23, 1945 to January 24, 1947.

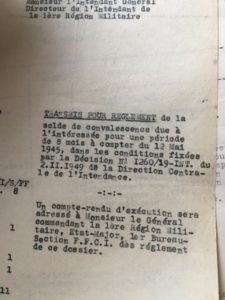

Record of reimbursement for her convalescence – Ref.GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

Record of reimbursement for her convalescence – Ref.GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

She must have remained in hospital after that date, because in 1948 she asked for reimbursement for a two-month stay in a rest and recuperation center run by the Association nationale des Déportés et Internés de la Résistance (National Association of Deported and Interned Members of the Resistance):

Ref.GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

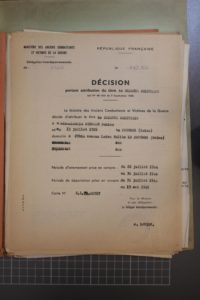

In 1950, she was granted a three-year temporary invalidity allowance because she was considered 25% disabled due to problems with digestion and the after-effects of vitamin deficiency.

Ref.21 P672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

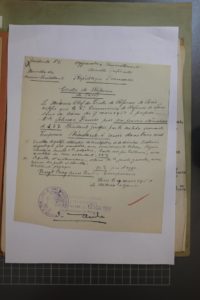

Meanwhile, she applied to be recognized as having been a political deportee. Certified to have been a corporal by the Résistance Intérieure Française (French Interior Resistance) in 1949, backed up by statements from other Resistance fighters (see above), her application for the title of political deportee was nevertheless refused in 1950 (see the document on the left), and again in 1952, because at that time she was recognized as having been deported on grounds of race (see the document on the right).

Refs. 21P 672 155 53633 and 21 P 672 155 53633, DAVCC, France – kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

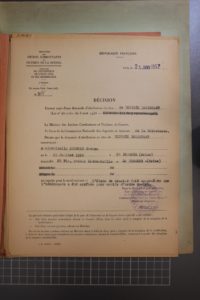

Her request was finally granted in 1953 :

Ref. 21 P672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

Ref. 21 P672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

The difficulty she encountered in gaining recognition as a political deportee can perhaps be explained by the fact that in 1948, 1949, 1951 and 1958, the EIF’s requests to have the “Sixth” recognized as a resistance movement and to integrate it into the RIF were refused (despite this having been approved initially in 1947):

Chronology of the refusal to recognize the “Sixth” as a Resistance movement, Ref. CMXLIII/4/5/1, Shoah Memorial in Paris Archives

Faced with these failed requests, the EIF finally gave up on this approach. Hence, in fine, she was granted the status of “lone Resistance fighter”:

Ref. P 672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

Her personal life after the war

On November 23, 1954, in the 9th district of Paris, Denise, who was by then a teacher in a business school, married a certain Léon Cohen, whom she later divorced. On April 23, 1976, she got remarried to Robert Kraemer, who had also been married before, in the 15th district of Paris.

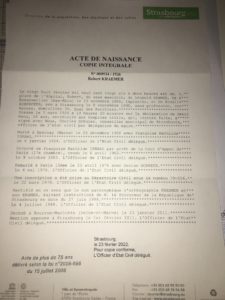

Robert Kraemer’s birth certificate RAEMER (Strasbourg City Hall, France)

Denise and Robert went to live in Bourron-Marlotte in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. Robert died there on January 23, 2011.

In 2015, on May 8, Denise Kraemer was made a knight of the Legion of Honor by the Prefect Jean-Luc Marx as part of the special 1939 – 1945 program. She was also awarded a medal of honor by the mayor of Bourron-Marlotte, Jean-Pierre Joubert, during the French National Day ceremony on July 14 of the same year:

“When you arrived at the camp, you raised your arm as a sign of resistance to violence and that is what saved your life the first time round, since you were recognized as “fit for work,”” said Jean-Pierre Joubert in his speech. “Fortunately, the Allied forces liberated the camp nine months after you were imprisoned, and that is why you are with us today. On this national holiday, which is also your birthday, since you were born on the night of July 14-15, 1926, I am pleased to present you with the medal of honor of Bourron-Marlotte, a town you love very much, and to wish you a very happy birthday”. (https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/melun_77288/la-resistante-denise-kraemer-a-recu-la-medaille-de-la-ville_6893441.html)

Denise did not have any children but her brother Maurice had several. We managed to contact his granddaughter (Denise’s great niece) on Facebook. Not having had very much contact with Denise and having been very young when she met her (she was about ten years old), she told us that: “Denise had never really talked much about that whole period of her life. She was very deeply affected by everything she experienced in her youth and the fact that they lost their father, who died in the camps in Poland.” (FaceBook Messenger conversation with Maëlys Huard, 17/05/2022).

Denise died on March 3, 2019, at the Hostellerie du Château, in Lorcy, in the Loiret department of France.

Denise Schneer’s death certificate (Lorcy Town Hall, France)

Denise Schneer’s death certificate (Lorcy Town Hall, France)

Denise is buried, along with her mother, Sophie Schneer, her sister Paulette Schneer and her husband Robert Kraemer, in the family vault at the Bagneux cemetery in Paris.

Photo of Denise Schneer’s grave in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris. (Division 3, line 8, tomb 5) Photo: M. Huard

Special thanks to Dorothée Boichard, librarian at the Shoah Memorial, and to Stéphanie Perrin, coordinator of educational activities at the Defense Historical Service, for their kindness, accessibility and efficiency.

Bibliography :

- M. Lafitte, Un engrenage fatal, Liana Levi, 2003

- R. Pozanski, D. Peschanski, Drancy, un camp en France, Fayard-Ministère de la Défense, 2015

- L’Album d’Auschwitz, Ed. AL-Dante-Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, 2005

- Régine Skorza-Jakubert, Fringale de vie contre usine à mort, Ed. Le Manuscrit- Fondation pour la mémoire de la Shoah, 2009

- Simone, Lison Bloch, Les petites juives de Kratzau, Ampelos, 2021

References :

- Ref. GR 16 P 540562, French Military Archives in Vincennes

- Ref. CMXLIII/4/5/1, Shoah Memorial, Paris, France

- Ref. CMXLIII/4/5/6, Shoah Memorial, Paris, France

- Ref. 21 P 672 155 53633, DAVCC, France, kindly provided by the Convoy 77 non-profit association

- Perreux-sur-Marne, Strasbourg and Lorcy town halls

- Register of naturalizations from December 26, 1896 (Bulletin des lois, Bulletin n°3065, Décret n°50350)

- Register of naturalizations from October 4, 1927, p.62 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/rechercheconsultation/consultation/ir/consultationIR.action?irId=FRAN_IR_057670&udId=AP004864&details=true&numberImage=DAFANCH94_NUMJ067790_D

- Fiches d’enregistrement au camp de Drancy de David et Denise Schneer (French National Archives, ref. F/9/5728)

- Order dated March 3, 2000 pertaining to the addition of the words “Died during deportation” to death certificates and declarations of death, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000000765169?init=true&page=1&query=mort+en+deportation+3+mars+2000&searchField=ALL&tab_selection=all

Links :

- https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-monde-juif-1984-4-page-153.html

- https://en.scoutwiki.org/Eclaireuses_et_Eclaireurs_isra%C3%A9lites_de_France

- https://www.eeif.org).

- http://www.ajpn.org/personne-Emmanuel-Lefschetz-3795.html

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/fr/map/gross-rosen-subcamps-1940-1945?parent=fr%2F6074

- https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/skorka-regine/)

- https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/yvette-dreyfuss/

- https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/melun_77288/la-resistante-denise-kraemer-a-recu-la-medaill

Français

Français Polski

Polski