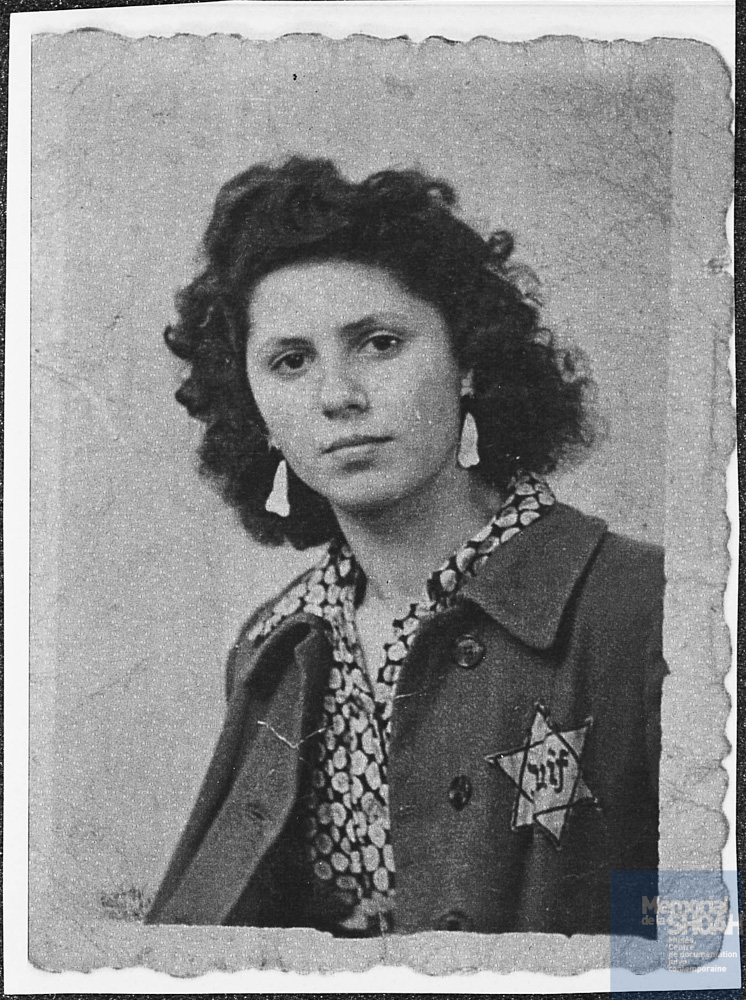

Fanny GDALEWICZ (1927-2011)

This biography of Fanny Gdalewicz, who was just seventeen years old when she was deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944, was researched and written by Clara Demurtas, a student at the Simone Weil high school in the 3rd district of Paris, under the guidance of Ms. Charbit.

Before she was deported, Fanny lived with her parents, Fiszel and Mechel, her sister Madeleine and her brother Jankiel at 14 Cité Dupetit-Thouars, a housing estate near the Carreau du Temple in Paris, just a stone’s throw from our high school.

We decided to focus our research on the neighborhood and environment in which Fanny Gdalewicz lived, before, during and after the war. To this end, we referred to Maël Le Noc’s paper, which concentrates on the geographical aspects of the Holocaust and explores the effects of anti-Jewish persecution on the everyday environment of two Parisian neighborhoods, Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges (AMER)[1], the second of which was home to the Gdalewicz family. Laurent Joly’s study of the Vel d’Hiv roundup, in particular what happened in the 3rd district of Paris[2] was another source of inspiration for our biography. In addition, Annaëlle Riou’s statistical analysis of the Convoy 77 deportees proved a valuable source of data.

Growing up in the Parisian “Yiddishland”

Up until the late 1920s, the area including the 3rd, 4th, 11th and 20th districts of Paris, which was home to many Jews of Russian or Sephardic Turkish origin, was known as “Yiddishland“. These were people of humble means who worked in the so-called “Jewish trades”: tailors mainly, but also bootmakers, cap-makers, leatherworkers, second-hand goods dealers, street vendors etc. Then in 1921-22, Polish Jews began to settle in the area, coining the phrase “Gliklekh vi Gott in Frankraych“(literally: “Happy as God in France”. “Happy as Larry” or “Happy as a clam”)[3].

In the 1920s, immigrants from Poland arrived legally, but this was no longer the case for the people who arrived from the mid-1930s onwards. Fiszel and Mechel Gdalewicz, together with their eldest son, Jankiel, who was born in 1919 in Warsaw, arrived sometime between 1921 and 1924. They both came from Latowicz, a little village in Mazovia, around forty mies from Warsaw. At the time of the 1921 census of Latowicz, there were 416 Jewish residents out of a total of 1,763, meaning that Jews made up 23% of the population[4]. In France, the couple held foreign worker’s identity cards. The Police Department kept them under close surveillance, which continued until the start of the Second World War. The Gdalewicz family was already aware of Anti-Semitism: in 1933, in a letter to the then Minister of the Interior, the mayor of the 3rd district of Paris, complaining about the influx of German Jews who had fled their homeland when Hitler came to power, described them as “human waste, unassimilable and morally harmful, peddling Freud’s theories”[5].

Fiszel and Mechel first lived at at 24 rue du Figuier in the 4th district of Paris, where they registered Jankiel with the town hall on September 19, 1924. They got married on December 20 of the same year. The street in those days was nothing like it is today: it was in an area that in 1921 had been identified as “îlot insalubre n°16” (“slum block n°16”). The number 16 reflects its position as one of 17 slums ranked in order of priority according to tuberculosis mortality rates between 1894 and 1918. This was a very poor and run-down neighborhood, where, before the war, up to 20% of Jewish households were living. Between 1942 and 1944, they were forcibly driven out and deported.

Their second child, Madeleine, was born in 1925 at the Rothschild Hospital in the 12th district of Paris. Several generations of Jewish immigrants were born there, before, during and after the Second World War.

Fanny Gdalewicz, their last child, was born on April 22, 1927. The parents’ determination to integrate into French society, despite their poor command of the French language and their isolated work and cultural environment, was reflected in the French first names they gave their daughters, and the fact that they arranged for the children to naturalized as French citizens in 1930. They did this as soon as they could, since foreign parents whose children were born in France could declare them to be French only after they had been resident in the country for three years[6]. As for the parents, according to French government terminology, they were still “of undetermined nationality of Polish origin”. In other words, they were stateless: they were not entitled to French nationality and in 1938 the Polish government passed a law that stripped Polish citizens of their nationality if they had been away from Poland for 5 years or more, a move that was aimed at Jews in particular.

In order to better understand the socio-economic environment in which the Gdalewicz family lived before the war, we consulted the Paris Census records, which are held in the Paris Departmental Archives, for the years 1926[7] and 1936[8]. There is an anomaly in the 1931 census records for the Enfants-Rouges district. The census registers list inhabitants by district, neighborhood and street, number by number. Everyone living in the dwelling is listed, and the census lists their date of birth, occupation, nationality and relationship to other members of the household. This information was collected by declaration (the residents declared and spelled their names, sometimes in broken French, and census-takers did not subsequently check their identity), so there can be differences from one census to the next. In 1936, for example, Fanny’s mother gave a different date of birth and first name from that on her civil status record[9]: her first name is listed as “Sura” and her birth year as 1892.

The census records provide an insight into the development of the neighborhood, and in the context of our research, they enabled us to estimate the date on which the Gdalewicz family moved to 14 Cité Dupetit-Thouars in the 3rd district of Paris. They were not at this address in the 1926 census, but according to the concierge’s post-war statement, they moved in during April 1928. We also wanted to find out whether Jews made up a significant proportion of the community in this neighborhood and in this street in particular, and what their backgrounds and professions were in the period between the two world wars.

If we look at the Cité Dupetit-Thouars housing estate in more detail, we see that there were many Jewish families living there, mainly on the odd-numbered side. In 1926, before the Gdalewicz family moved in, there were two or three Jewish households in each building, with around twenty apartments on the odd-numbered side of the estate. These were simple, plaster-fronted, four-story buildings above storerooms and workshops with a wide, 425-foot-long thoroughfare, built in 1841. Most of them worked in the so-called “Jewish trades”. Russian Jews were fairly numerous, and Poles were the second most common nationality. On the even-numbered side, at numbers 2, 4, 6 and 12, there were no households at all with Jewish-sounding names. These were stone buildings built to a higher standard than those on the odd-numbered side. There was just one Jewish household out of a total of 59 at number 8 and 2 out of 19 at number 14, the building in which the Gdalewicz family set up home two years later.

Fanny’s mother died in 1936 at the age of 31, but she was still listed in that year’s census. She must therefore have died shortly after the census was carried out.

The 1936 census revealed significant changes in the neighborhood. The number of Jewish homes was much higher than it had been ten years earlier, particularly in the Cité Dupetit-Thouars. On the odd-numbered side, at numbers 5, 7 and 9, the number of Jewish households had doubled since 1926. At no. 11, the heads of household in 7 out of 9 families had Jewish-sounding names. This time, the majority of households were Jewish immigrants from Poland, and many of the names were new, suggesting that they had only arrived recently, in the 1930s[10]. As for the even numbered homes, the pattern was much the same as in 1926: there were no Jewish households in number 2 (out of a total of 25), nor in number 4 (out of a total of 14). At number 6, on the other hand, 7 of the 55 heads of household had Jewish-sounding names. None of them had been naturalized as French citizens, and their occupations were once again typical of a recently migrated population. At number 8, there were 15 households, including 9 with Jewish-sounding names. Number 12 was home to 5 Jewish households out of a total of 30, while number 14 had 20 households, 4 of which were probably Jewish. Only the children of these families were French citizens. Hardly any of the adults were naturalized French citizens. They all came originally from Poland.

The Gdalewicz household included Fiszel, a tailor born in Poland in 1894, his wife Sura, a seamstress born in Poland in 1892, Madeleine, born in Paris in 1925, listed as Polish rather than French and Fanny, who was born in 1927 and listed as a French citizen. Their older brother Jankiel, who was born in Poland in 1919, is not mentioned at all, even though he was only 17 years old in 1936. According to his deportation record[11], he too was a tailor. He had probably left home very young and went to live elsewhere in Paris. Also living at number 14 was the Guy family, who were not there ten years earlier: the father of the family, Charles-Edouard Guy, was a mason, and his son Fernand, born in 1924, was a tailor. After the war, in 1946, he married Madeleine Gdalewicz and the couple had a son, Serge, in 1947.

As a young girl, Fanny went to the Béranger elementary school at 3, rue Béranger. Like many girls raised in low-income families, she began working at the age of 14 as a seamstress, following in the footsteps of her older sister Madeleine. The whole family worked in the textile industry. At the time, the Jewish population was made up of day laborers, street traders, craftsmen and shopkeepers. The women were often seamstresses or embroiderers, mostly working from home. There was little separation between work and family life, and apartments were typically made up of just two rooms with no facilities, so life was tough.

The Cité Dupetit-Thouars from 1940 to 1944

As Maël Le Noc explains in her study of Jewish persecution in the Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges neighborhoods, during the Occupation, “Parisian neighborhood police departments carefully logged the records of the Jewish registration process with which they were associated”[12]. While the majority of these records were destroyed after the war, the police department in this district kept them, including lists of the “Jewish race” census of October 1940, the list of homes with radios to be confiscated in September 1941, and the list of yellow stars distributed in June 1942. There is also a list of people who had their food cards stamped “Jewish” in January 1943. These records were passed on the Police Headquarters Archives[13]. This is therefore an especially interesting neighborhood to study.

Prior to the October 1940 census, the most recent census that included religious affiliation was that of 1872. In Paris in 1940, the Jewish community, based on the sound of family names, represented around 1.5% of the total population. However, in the 3rd district of Paris, the Jewish population accounted for almost 15% of the total. In a number of streets and public places in the Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges districts, the influence of Jewish culture is clearly visible. These include rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth, where there is a synagogue, and the streets around the Carreau du Temple, which includes the Cité Dupetit-Thouars housing estate. In these two districts, 2851 French Jews and 2761 foreign Jews were listed on October 20, 1940, this being 16% of the total population of these districts, a figure well above the average for Paris. Maël Le Noc found that there was an especially high density of Jewish households in the Cité Dupetit-Thouars housing estate[14].

According to Serge Klarsfeld’s data, taken from his book Mémorial de la déportation (Memorial to the Deportation), 1,327 Jews were deported from the two districts (out of a total of 5,532 people from 2,150 households), and 89% of them were identifiable on the list of people of the “Jewish race” from the October 1940 census. This represents one in five people. A very significant number of people (577) under the age of 18 were deported from the 3rd district as a whole[15]. Fanny, who was only 17 when she was deported, was among them. During her research, Maël Le Noc was able to establish that “between October 1940 and August 1944, the Jewish population of AMER (Arts-et-Métiers / Enfants-Rouges) fell by at least 85% under the combined effect of arrests and escapes. The phenomenon is particularly noticeable in the Enfants-Rouges district, where the intensity of the Vel d’Hiv round-up was lower than that in the Arts-et-Métiers district. At least 3,000 Jews, half of them foreigners, tried to flee the 3rd district or go into hiding“.

The fact remains, however, that it was during this roundup that Fanny and Madeleine’s brother Jankiel and their father Fiszel were arrested. Laurent Joly, a historian, has studied the events of July 16 and 17, 1942 in the Enfants-Rouges district in particular[16]. Maxime Morisot, superintendent of the municipal police department in the 3rd district, had 2675 people on his list in an area that was easy to surround: “the 3rd district has by far the highest density of “arrestable” Jews per square meter in the capital”[17]. With this in mind, he mobilized 70 police officers and requested reinforcements from the 1st and 14th districts, making a total of 312 “capturing agents”.

The meeting place was a garage on rue de Bretagne. This was a particularly busy street, and the operation took place right opposite the Enfants-Rouges covered market, in full view of the public. Three buses were made available to transport the people captured to Drancy internment camp or to the Vélodrome d’Hiver (winter cycling track), in the 15th district of Paris. As Laurent Joly explains, at 4am on July 16: “The police involved reported to their local police department, based at the town hall at 5 rue Perrée in the 3rd district. Less than an hour later, they began knocking on doors”[18]. It is unclear whether Jankiel was arrested at the same time as his father at 14 Cité Dupetit-Thouars, or whether they were transferred to the Vel d’Hiv stadium or taken straight to Drancy. As the day progressed, the police also began arresting Jews in the street and in the subway. The three buses requisitioned from the Paris transit authority (RATP) were no longer enough, so more were brought in and stationed at the Temple subway station.

In his semi-autobiographical novel, Les guichets du Louvre (literally, The Louvre ticket offices), Roger Boussinot recalls the terrible day of July 16, 1942, as he crisscrossed the 3rd district, trying to help Jews cross to the opposite side of the river Seine to escape the roundup. His precise, detailed account captures the horror of that day, when the banality of everyday life collided with the extraordinary circumstances of the roundup as “a moment of horror and astonishment in the city”[19].

Jankiel was deported on Convoy No. 7, which left Drancy on July 19, 1942, while Fiszel was deported on Convoy No. 9, which left Drancy on July 22, 1942. The parents of Israël Grodnicki, Fanny’s future husband, were also on deported on this transport. Israêl’s sister, Hélène Rajchgod née Grodnicki, her husband Hersz and Hersz’s younger brother, Daniel Rajchgod, were deported from Pithiviers on Convoy no. 16. Hélène and Hersz had a son, Jacques, who was just 9 months old at the time of the round-up. In a state of panic, they tried to escape to the free zone, but they were caught. They did, however, at least manage to save their son by leaving him in the care of an unknown woman.

Neither Madeleine nor Fanny were caught during the Vel d’Hiv round-up. None of the Jewish children in their building are listed in the database of Holocaust victims. We can only assume that Jean, Salomon and Hélène Fiszelewicz, Joseph Orzolet and Marcel Grun were sent into hidden, in Paris or elsewhere, before, during or after the round-up.

The Tysz family, on the other hand, who lived at 6 Cité Dupetit-Thouars, were arrested and deported, never to return. Two families were rounded up at number 8: the stories of the Lisiak and Wejdman families are particularly poignant, as they were separated after the roundup and later murdered, never having set eyes on each other again: Jacob Lisiak was deported at the same time as his neighbor Abraham Tysz on July 31, 1942. He died in Auschwitz in June 1943. His wife, Marie Lisiak, was deported on Convoy 16 on August 7, 1942. Their daughters Jenny and Henriette, born in 1930 and 1939, were deported on Convoy 21 on August 19, 1942. As for the Wejdman family, Icek, the father, was deported from Pithiviers on Convoy 13, along with his neighbors Jacob Lisiak and Abraham Tysz, while their children Léon, who was born in 1929, Fanny, who was born in 1932, and Maurice, who was born in 1937, were deported on Convoy 24 on August 26. Their mother, Hélène, and youngest child, Claudine, born in 1941, were the only ones who survived.

The arrest rate in the 3rd district of Paris was slightly lower than that of the department as a whole[20]. Laurent Joly notes that the districts with the densest population of Jews were also those where the roundup was the least “successful” in percentage terms: solidarity and word of mouth undoubtedly played an important part in this.

After the roundup, many of the residents fled the Cité Dupetit-Thouars as they saw it as a mousetrap, but some were caught as they were trying to escape, in particular the women, many of whom attempted to cross the demarcation line, either with or without their children, during summer 1942. Feigel Bagno and her daughter Anna, who was the same age as Madeleine Gdalewicz, lived at no. 5 until July 1942. They were captured on the demarcation line and deported from Pithiviers on Convoy 35 on September 21, 1942. Henriette Szer, née Sciarke, who was born in 1920, lived in the same building. Having joined the Resistance after her husband, Kril Szer, was arrested during the “green ticket” roundup[21], she was arrested by the Gestapo in Vendôme, in the Loir-et-Cher department of France, in November 1943, deported to Auschwitz in January 1944 and transferred to the Kratzau camp in October the same year. Malka Grun, who also lived in the same building as the Gdalewicz family and had sought refuge in the Limoges area in the Haute-Vienne department, was deported on Convoy 55 on March 26, 1943. Her husband, Michel, and her son, Marcel, however, are not listed in any of the Holocaust victim databases. Sira Szaluta, who arrived in Paris in 1926, lived at no. 8 with her husband David and their son Jacques, who was born in 1933. David was rounded up in May 1941 and deported on Convoy 1 from Compeigne on March 27, 1942. Sira and Jacques crossed the demarcation line after the Vel d’Hiv round-up. Having managed to find a safe place for her son, she was arrested in Lyon in the summer of 1944 and then transferred to Drancy camp. She was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77, along with Fanny Gdalewicz, and then transferred to Kratzau in the autumn of 1944.

In the summer of 1942, Fanny and Madeleine opted to stay on in Paris. In January 1943, they went to the Enfants-Rouges police headquarters to collect their special food ration cards for Jews. By mid-1943, some 60,000 Jews were still living in Paris. In February-March 1943, most of the roundups took place in the southern zone. In 1944, the persecution continued but not to the same extent as in 1942-43, and the roundups were smaller and more sporadic.

On February 3, 1944, Mr. Hennequin, the chief of municipal police at the Paris Police Headquarters, sent a confidential memo to all divisional and highway police chiefs, in which he passed on a request from the German authorities to arrest all Jews, regardless of nationality, and transfer them to Drancy. In practice, it was mainly the Germans, and in this case the Gestapo, who handled the arrests, with the help of the collaborators in the Militia. They scoured hospitals, kindergartens and UGIF children’s homes and also arrested people at random on the streets and in the subway. This was how Fanny was arrested at the end of June 1944.

Arrest and deportation

On the morning of June 30, 1944, Fanny was stopped by two plainclothes German officers as they got out of a car at the corner of boulevard de Bonne-Nouvelle and rue du Faubourg Poissonnière, just as she was on her way to work. At the time, she was working in the fur trade. The reason for her arrest was given as: “out during the alert“. The Allies had landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944, and the fighting was intense. Paris was buzzing with alerts and the Gestapo and the Militia had increased the level of repression. On June 28, 1944, Philippe Henriot, who was the voice of the French collaborators on Radio Paris, an active member of the Militia and the recently appointed Secretary of State for Information and Propaganda in the Laval government, was assassinated by a Resistance unit in Paris. The Militia retaliated with extreme force, arresting people left, right and center.

Fanny was initially taken to 11 rue des Saussaies, a building that had first housed the General Security service and, since 1934, the French Government’s National Security service. They also served as the headquarters of Section IV, which was responsible for deciding which of the people arrested should be brought before the military tribunal at 11, rue Boissy d’Anglas in the 8th district of Paris, and which of them were to be deported without trial. As a Jew, but one who was not involved in the Resistance, Fanny was then transferred to 84 avenue Foch, the headquarters of what was known as the “French Gestapo”, which had been run by René Launay, a.k.a. “Lauris”, a.k.a. “René le dingue” (“René the madman”), since 1943. A far-right collaborator, Launay was an intelligence officer for Marcel Déat’s Rassemblement National Populaire (“National Popular Front”). It was from a window on the 4th floor of this building that, a few months earlier, on March 22, 1944, Pierre Brossolette, a Resistance fighter who had been tortured for two days, jumped to his death. A note from the authorities of the 8th district, dated June 30, 1944, and addressed to someone with the initials “P.M”, gives us an idea of the way in which the authorities dealt with such transfers: “I am sending to the detention center the Jewish woman Fanny Gdalewicz, single, fur worker, arrested today by the German Police for Jewish Affairs, of 11 bis rue des Saussaies, pending her internment“.

Fanny arrived at Drancy camp on the day that Convoy 76, with a thousand prisoners on board, left for Auschwitz. The camp, which since June 1943 had been run by Aloïs Brunner, was in its final stages. Brunner was a key player in the German plan to deport Jews to France. “While the Allies were advancing and the French and German police were concentrating on the Resistance, Brunner crisscrossed Paris and the suburbs in his private car, picking up a Jew here, a Jew there (…) Whether Germany was victorious over the Allies or not, Brunner was banking on victory against the Jews. As the Allied troops were approaching Paris, Brunner moved mountains to send off another convoy, packed full of his pickings from labor camps, prisons, orphanages, hospitals and street arrests (…). He achieved his goal of sending 1,300 people on July 31, 1944, including 300 children taken from orphanages”[22] . A more recent count puts the number of children taken from UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) institutions in and around Paris at 130.

The French Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War later deemed Fanny Gdalewicz to have been in detention between June 30, 1944 and June 1, 1945. Everything we know about Fanny comes from a series of sworn statements and testimonials signed by fellow prisoners at Auschwitz and the Kratzau camp in Czechoslovakia, members of her family and her neighbors, after the paperwork issued to her by the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War when she returned from the camps in 1945 was lost. These records, which are held at the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, in Normandy, enabled us to retrace her journey.

In addition, we drew on Master’s student Annaëlle Riou’s[23] prosopographical analysis of Convoy 77, in which she systematically analyzed the 1,152 deportees files held at the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of the Defense Historical Service. Of the 1152 people, 849 died in the camps, 246 were “status claims” (people who applied for to be granted the status of deportee), including that of Fanny Gdalewicz, and 57 were interned Resistance fighters. We set out to determine how closely Fanny’s profile resembled those of the other Convoy 77 deportees and survivors. We have come to the conclusion that it is fairly typical of the make-up of the convoy, and of the individual stories that can be reconstructed thanks to Annaëlle Riou’s research.

First of all, we were struck by the high proportion of deportees who were French citizens, as was Fanny: 69%. This was also true of the previous convoy, demonstrating the extent to which the hunt for Jews no longer took account of their nationalities in the final stages of the war. Secondly, Fanny was one of the 668 people on this transport who were born in Paris and the inner suburbs, i.e. 52% of the total number of deportees. Many were born between 1925 and 1927, and almost 40 of them, including Fanny, were born in 1927. The majority, 52%, were women and girls, only 12% of whom were adults. Most of the girls, like Fanny, were deported on their own. What is particularly striking, of course, is the number of children under 18: 347.

When Convoy 77 arrived from Drancy, the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex was in the midst of a frenzied extermination operation, during which some 420,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered. On some days in July and August, 1944, five convoys arrived in Birkenau, bringing in as many as 16,000 people.

Convoy 77, which left Bobigny station at 10 a.m. on July 31, arrived at the Birkenau camp in the early hours of August 3, at around 3 a.m. Around 70% of the deportees were sent to their deaths in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived (890 people in total, 425 women and 465 men) and the remaining 30% were sent to work in the camp. Statistically, according to Annaëlle Riou’s research, the people most likely to survive were born between 1904 and 1927, and the majority of them were women. In fact, more women than men were selected to work in the camp. Fanny, who was 17 and on her own, was one of the 388 people selected and tattooed as they entered the camp. The registration numbers of 191 people are known. The women’s numbers were A 160128 to 16 833, while those of the men were B 3686 to 3958. Fanny was assigned number A 16723.

From October 1944 onwards, some of the women from Convoy 77 were transferred to other camps. Only 111 deportees stayed on in Auschwitz and were never sent anywhere else. Many of the women were transferred to Gross Rosen, or, more specifically, to the Kratzau (Chrastava) work camp in Czechoslovakia, including 122 women from Convoy 77. Most of them left Auschwitz on October 28, 1944, with a 185-mile journey ahead of them. Fanny Gdalewicz arrived in Kratzau in December 1944. The DAVCC archives hold an unsigned testimonial detailing the location of the camp and the living conditions within it[24]. It was a complex in which 500 Jewish women were interned, around 300 of whom were French and 200 were Dutch. The camp was based in Weisskirchen, about 2 ½ miles from Kratzau. The living conditions were nothing like those in Birkenau. The work was exhausting, but there was heating and hot water, and all of the women had their own straw mattress to sleep on. This was no doubt one of the reasons that many of the women from Convoy 77 who were transferred to Kratzau survived.

The women got up at 3:30 a.m. and worked in an ammunition factory until 7:00 p.m., six days a week. The report also mentions the appalling sanitary conditions and the lack of clothing and shoes, but does not document the period in spring 1945 when the Russian army arrived and liberated the camp.

Simone and Lison Bloch, two sisters who were born in 1926 and 1929 and were also deported on Convoy 77, gave their testimony in 2012 in the form of a typed account which is held in the library of the Shoah Memorial in Paris[25]. In it, they describe the living conditions in the Kratzau camp and explain what happened when they were freed.

While she was in Kratzau, Fanny met up with two of her neighbors from the Cité Dupetit-Thouars housing estate, which is quite remarkable. The first was Henriette Szer, who was 7 years older than Fanny and lived at 5 Cité Dupetit-Thouars with her husband, who was rounded up in May1941[26]. The other was Sira Szaluta, née Wajnryb, who was born in 1910 and spent her childhood at 8 Cité Dupetit-Thouars, where she lived with her parents until she got married and moved to rue St Maur.

The prisoners realized that the end was near in around March, when a female guard told them that Hitler was dead. The Germans held out until the bitter end, however. They only left the day before the Russians arrive to liberate the camp on May 9, 1945.

After the Liberation

Fanny was repatriated from Kratzau to Sarrebourg, in the Moselle department of France, on June 2, 1945. This was one of the many transit points for returnees, including prisoners of war, “racial” deportees as they were then called, resistance fighters and people who had been sent to do forced labor. It was the Jews who arrived in the worst state, having been interned in several camps and often having had to take part in the death marches. The healthcare service for repatriated people drew up a protocol for use in all the reception centers, which took into account the need for prompt, if limited, medical examinations. They needed to keep the centers running, given that they had to examine up to 10,000 people a day in May and June 1945.

Fanny arrived in Sarrebourg at the peak of the repatriation operation, which began in April 1945 and continued until July. The process was organized in such a way that all the paperwork and medical checks were done in 1 hour and 10 minutes. Health procedures involved showering with disinfectant and applying insecticide powder, treating skin conditions if necessary, a brief physical examination and a chest X-ray. At the end of the process, the person was issued repatriated receives a “repatriation card”, which could be used as an identity card[27]. The French National Federation of Deportees and internees, Resistance fighters and Patriots (FNDIRP) also issued Fanny with an internment certificate.

On September 30, 1945, the French Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War issued Fanny Gdalewicz, who had lost her identity paperwork, with a deportation certificate. This was the first loss of many, but for us, as we were trying to reconstruct her life story and write her biography, it was a bit of luck. Not long afterwards, in the summer of 1946, her deportation certificate was destroyed in a fire while she was staying at Menthon Saint-Bernard in the Haute-Savoie department of France. The Departmental service for Prisoners, Deportees and Resistance fighters issued her with a receipt, certifying that she had received a payment of 3,000 francs when she returned from the camps. On November 2, 1948, in keeping with the provisions of a law passed on September 9, 1948, she was granted the status of “political deportee”, meaning that she had been deported for political reasons. When she lost her card again, Fanny approached her family and friends to ask for the necessary statements to be issued with a new card, which she received in 1954.

What might it have been like to be back in the Enfants-Rouges neighborhood after the war?

Mael Le Noc investigated the geographical impact of the persecution of Jews on the Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges districts from 1944 to1946[28] : According to him, this question is “a missing aspect of geographical research into the Shoah”. He goes on to explain that “at the time of the Liberation, fewer than 850 Jews, in 520 households, were still living “openly” in Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges, which is less than 15% of the 1940 Jewish population”.

Madeleine and Fanny return to 14 Cité Dupetit-Thouars after their father and brother died. Madeleine married Fernand Guy, a neighbor, on June 22, 1946, and they left Paris for Dijon, in the Côte-d’Or department of France. As for Fanny, she did not go very far at all: she met her fiancée, Israël Grodnicki, just a block from where she lived. Born in Paris in 1924, he had moved to the neighborhood with his parents at around the same time as the Gdalewicz family. They lived at 1 rue Perrée. His father David, mother Raya and older sister Sarka [29] were all born in Poland. The only one of his family to survive, he went back to live at his previous address after the war and set up his own tailoring business there. Israël was one of two witnesses at Madeleine Gdalewicz’s wedding in 1946, and he struck up a romantic relationship with her younger sister, Fanny. There was three years between them. They were married at the town hall of the 3rd district of Paris in 1948 and lived at 1 rue Perrée for the rest of their lives.

For the survivors, however, moving back to the same neighborhood was necessarily a foregone conclusion, as Maël Le Noc’s study of the 1945 real-estate survey[30] which was intended to identify unoccupied or under-occupied premises at a time of a housing shortage, shows. By analyzing this data, together with the 1946 census of Paris, we were able to gain a better understanding of changes in the Jewish population in Paris after the Liberation. The researcher points out that in the Cité Dupetit-Thouars, only 20% of the Jews living there before the war had returned at the time of the Liberation, and 54% had returned by 1945.

Israël Grodnicki died on October 20, 1948. When Fanny died in 2011, she was still living at 1 rue Perrée.

Notes and references

[1] Maël Le Noc used the acronym AMER for the Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges districts.

[2] L. JOLY, “Ils ont emmené votre maman et votre petite sœur… La grande rafle du 16 juillet 1942 à l’échelle d’un quartier du 3e arrondissement de Paris” (“They took your mom and your little sister… The great roundup of July 16, 1942 in a neighborhood in the 3rd district of Paris”), Histoire urbaine (Urban History) n°62, December 2021, p.37 à 57.

[3] “Happy as God in France”, in Yiddish, meaning “Happy as Larry” or “Happy as a clam”)[3] At a time when Central European Jews felt that the country that treated Jews best was France, the “land of Enlightenment” and Jewish emancipation, this expression was in vogue. Its exact origin is not known.

[4] Source: https://sztetl.org.pl/en/node/1837/99-history/137570-history-of-community and Latowicz, [in:] Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, vol. 4: Warsaw and its region, ed. A. WEIN, Jerusalem 1989, p. 244.

[5] NOIRIEL G., Réfugiés et sans papiers. La République face au droit d’asile, XIXe-XXe siècle, (Refugees and undocumented migrants. The Republic and the right of asylum, 19th-20th century ) Fayard, 2012.

[6] Born in 1927, Fanny was able to take advantage of a particularly liberal law passed the same year, enabling her to become a French citizen by naturalization after three years’ residence in France, rather than the 10 years which had been required since 1889.

[7] AP D2M8 224

[8] AP D2M8 549

[9] The marriage certificate, issued at the town hall of the 4th district of Paris in 1924, lists Mechel Zajac as having been born in 1905. This date is questionable, however, given that Jankiel, her first child, was born in 1919.

[10] Historians estimate that 50,000 Polish Jews arrived in France between 1918 and 1939, of which 35,800 settled in Paris. See M.C. BLANC-CHALEARD, “Les étrangers, des Parisiens à l’épreuve des convulsions nationales, 1840-1940” (“Foreigners and Parisians confronted with national upheaval, 1840-1940”.), in J.P. AZÉMA (dir.), Vivre et survivre dans le Marais. Au cœur de Paris, du Moyen-âge à nos jours, (Living and surviving in the Marais. In the heart of Paris, from the Middle Ages to the present day) Le Manuscrit, 2005, p.279-293.

[11] Jankiel GDALEWICZ (Shoah Memorial)

[12] M. LE NOC. , “Évolution de la population juive parisienne pendant l’Occupation” (“Changes in the Jewish population of Paris during the Occupation “), Tsafon, n° 84, December 2022, pp. 83-102.

[13] APP BA2433 sub-series ID16, 04 for the October 1940 “race” census and 05 for the Jewish star list.

[14] M. LE NOC., “Présences, proximités et disparitions. Une approche spatiale de la persécution des Juifs à Paris, 1940-1944 “,( “Presences, proximities and disappearances. A spatial approach to the persecution of Jews in Paris, 1940-1944”) Histoire Urbaine n°62, December 2021, p.15-36.

[15] Source: tetrade.huma-num.fr/

[16] L. JOLY. , “Ils ont emmené votre maman et votre petite sœur …La grande rafle du 16 juillet 1942 à l’échelle d’un quartier du 3e arrondissement de Paris” (“They took your mom and your little sister… The great roundup of July 16, 1942 in a neighborhood in the 3rd district of Paris”), Histoire urbaine n°62, December 2021, p.37- 57.

[17] L. JOLY, article cited

[18] L. JOLY, article cited.

[19] L. JOLY, article cited.

[20] 29%, as against 32% for Paris as a whole, JOLY, art.cit.

[21] The first round-up carried out in Paris. It targeted foreign Jewish men. Around 6500 Jews, the majority of them Polish, were sent a summons for “an examination of their situation”. They had to report to designated facilities in the 4th, 10th, 11th, 19th and 20th districts. A total of 3,710 people were arrested and taken to Drancy or Compiègne-Royallieu. These men formed a large proportion of the deportees on Convoy no. 1 on March 27, 1942.

[22] M. FELTSINER, “Commandant de Drancy : Alois Brunner et les Juifs de France”, (“The Commandant of Drancy: Alois Brunner and the Jews of France”,) Le Monde juif, (The Jewish World) 1987/4, n°128, p.143-172.

[23] RIOU A. , Une micro-histoire de la Shoah en France. La déportation des Juifs du convoi 77, (A micro-history of the Holocaust in France. The deportation of the Jews on Convoy 77) Second year Master’s student, supervised by Gaël Eisman, UFR Humanities and Social Sciences, Univeristy of Caen-Normandie)., 2018-2019.

[24] Defense Historical Service, Caen, 26P 1118, Gross Rosen, Kratzau commando “Renseignements” (“Information”).

[25] C’est du rab de vie que tu te tapes là ! (That’s a lot of extra life you’re getting!) Testimonial taken and written by Remi Warnery, 2012.

[26] In 1952, she testified to Fanny’s presence in Auschwitz and then in Kratzau, Czechoslovakia, at the time when Fanny had lost her deportation card again.

[27] D’après le témoignage de Pierre Bourgeois, médecin- directeur du Service de rapatriement des prisonniers, des déportés et réfugiés entre 1944 et 1946 que nous avons trouvé en ligne : https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CAIQw7AJahcKEwio9If22Pn_AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.biusante.parisdescartes.fr%2Fsfhm%2Fhsm%2FHSMx1992x026x003%2FHSMx1992x026x003x0167.pdf&psig=AOvVaw28q4bksa9ryCaitiPTXLHn&ust=1688719440189156&opi=89978449

[28] Excerpts from a paper presenting the foundations and initial results of a postdoctoral research project entitled “Une approche spatiale de l’après-Shoah à Paris; le cas des quartiers Arts-et-Métiers et Enfants-Rouges, 1944-1946”. (A spatial approach to the post-Shoah period in Paris: the case of the Arts-et-Métiers and Enfants-Rouges districts, 1944-1946). It was presented orally at the annual seminar of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah on January 6, 2022. Available online at:

[29] Born in 1921.

[30] Fichier Immobilier (property survey), 3966W, Paris archives

Français

Français Polski

Polski