Félix ZIRAH

A Tunisian deported to Auschwitz

Danielle Laguillon Hentati

Let me tell you,

Let me testify,

Yes, the earth opened its mouth,

The abyss swallowed them.

I am this abyss

And this burnt flesh,

I am the cry that dies in my mouth,

I am their strangled voices [1].

The Second World War was a time of unprecedented violence and crimes against humanity. While the survivors were able to testify to the horror of the camps, and to describe the dehumanization suffered by the victims, the dead, on the other hand, were silent, their lips forever closed to their suffering. Their mass murder, the genocide, was deliberate and planned by the Nazi system, which turned these men, women and children into “Untermenschen“, their humanity denied by Nazism. Reduced to ashes, with no graves to commemorate them and no inscriptions in their memory, they fell into the shadows of anonymity.

The purpose of the Convoy 77 project is to retrace the life of each of the victims who was aboard this death train: who they were, how they lived and why they died. The last transport to leave Drancy on July 31, 1944, convoy number 77 included 10 Tunisian-born Jews who all died in Auschwitz [2] : Dario Boccara, Abraham Albert Boucara, Fortunée Brakha, Laure Cohen née Taieb, Joseph Franco, Gaston Nataf, Gaston Secnazi, Gaston Elie Setbon, Emile Smadja and Félix Zirah.

In order to better understand Félix Zirah’s personality, and to place him in his family tree (which I had to put together) and his family’s story, I had to consider the social context of the interwar period, where the notion of a “foreigner” who had become an “undesirable” and a Jew who had become a public enemy, soon emerged. Then, in the context of the war, it was necessary to refer first of all on his deportation dossier[3] which formed a basis for the research, as then on files from the Fort de Montluc prison and Drancy, and Yad Vashem records[4]. Nevertheless, the information provided was sketchy, as it only established the fact that he had been deported in order to have his civil status regularized and to settle his estate, but not to request any special status for him. With this alone, it would not have been possible to write the biography of Félix Zirah, since his life story appeared to be incomplete, with an enormous gap between 1929 and 1944. However, the fortuitous discovery of three archived files pertaining to him, the first two in the French National Archives[5], then another in the Rhône departmental archives in the Foreigners’ Check series[6], made it possible to at least partially bridge this gap. From March 20, 1929 to August 22, 1933, this collection of letters details the administrative and police procedures to which Félix Zirah was subjected, followed by two legal convictions, all due to the climate of mistrust of foreigners which existed in France at the time.

These files shed a different light on the man that was Félix Zirah and shattered any beliefs that I might have had about this “fine man”, a Tunisian who emigrated to France, an embroiderer who became a jewelry broker and died as a result of deportation. Who was Félix Zirah, really?

In addition, guided by the somewhat imprecise oral recollections of “Tata Simone” [7], I then focused my research on civil status records and censuses, as well as on the newspapers of the time. I would like to thank two people whose help was invaluable: Séverine Zirah, Félix Zirah’s great-grandniece, who told me what the family collective memories had passed on to her, and Moché Uzan, assistant to the Chief Rabbi of Tunis, who provided me with civil status records.

Taken all together, the snippets of family memories, civil status records, archived material and press articles have enabled me to reconstruct Félix’s life story.

A Jewish family in Tunis

Félix Zirah was born on August 5, 1892 in Tunis, the capital of the Regency which was a French Protectorate.

The family lineage of the Zirah family begins with Félix’s parents, about whom we have little information, because they were among the Tunisian Jews, commonly known as twansas, whose marriage certificates, ketubbot, have only been recorded in the archives since 1898 [8]. His father, Joseph Zirah, who was born around 1860, was perhaps this merchant, living in Tunis, who was appointed along with David Uzan as “guardians of the minors David, Isaac, Julie and Alice Uzan, sole heirs of their late father Haï de David Uzan” by virtue of a rabbinical decision dated September 26, 1897 [9]. Joseph died before May 28, 1921, the date of his son Élie Émile’s wedding. His mother, Esther Sarfati, born around 1865, was in Paris in 1921 with her two sons; she died before January 16, 1926, the date on which Félix got married.

Joseph and Esther Zirah went on to have 5 children. Firstly, they had 3 girls:

Leila Hélène (Tunis 1884 – Neuilly-sur-Marne 1953) who married, on March 23, 1903 [10] in Tunis, Jacob Jacques Setruk (Bizerte 1880 – Paris 1930); the couple had two children born in Bizerte: Albert François [11] and Olga who, due to an administrative quirk, had their surname changed to Setruck.

Next, Émilie (Tunis 1889 – Le Plessis-Robinson 1949) who was married on May 27, 1903 in Tunis to Jacques Marzouk (Tunis 1873 – Neuilly-sur-Marne 1933). They had two children, born in Tunis: Toto Marcelle and Maurice Joseph, who was to play an important role within the family.

The third daughter was Fortunée (Tunis about 1891 [12] – Paris 1942) who got married in Tunis to David Smadja (Tunis 1884 – Auschwitz 1942). The couple has one known child, Élie Émile Smadja, born in 1909 at 1, rue Sidi Sofiane, in the brand new quarter of Le Passage [13] in Tunis where many Jewish families settled, leaving behind the old Jewish district of La Hara, which was crowded and unhealthy.

Le Passage

For many of them, this was the beginning of an upward social mobility in a protectorate that facilitated their cultural integration and assimilation.

“France thus offered these elites the framework of republican culture, impregnated with the universalist values of the Revolution and portrayed as a universal culture. The ideology of l’École de la République (the School of the Republic) was to arouse great enthusiasm in the Jewish community. […] The universalist culture, associated with the Protectorate, was all the more suitable for others [editor’s note, non-Zionist Jews] as it allowed them to evade the national dimension while offering an escape from domination. The Jewish elite, unlike the Arab elite, did not have to construct and propose to the country a Tunisian national identity, but rather to affirm a community identity in partnership with the other various communities present in Tunisia, with the guarantee that republican and secular France provided. All they had to do was to reject a straitjacket of traditions and religious precepts, rather than a reflexive Judeo-Arabic culture, in order to adopt the values of the culture which, along with school, was the only way to promote themselves and acquire a more valued social status. [14] “

Lastly, they had two sons: Félix and Élie Émile (Tunis 1895 – Crosne 1985).

The Zirahs do not appear to have been devoutly religious, since Joseph and Esther’s descendants entered into marriages with French men or women who were not of the same faith. These mixed marriages were part of the evolution of the well-to-do, cultured, but above all “Frenchified” fringe of the Jewish community in Tunis, who were moving away from the customary endogamy and from assiduously practicing their religion, although they did not deny their culture. They were “becoming westernized”, as it was described the time, due to changes in their way of life: abandoning Le Hara to live in the Le Passage or Lafayette neighborhoods in new, light, bright apartments; wearing modern clothes; giving French first names to children and sending them to school to get a good education and increase their chances of social advancement etc.

The Zirah family in France

According to some press reports and research into these people, various Tunisians with the surname Zirah, all of whom were traders, settled in France at the end of the 19th century. The first of them seems to have been Mardochée Zirah, who was born in Tunis in 1869 and was the son of Elijah and Rachel Cohen. A commercial traveler, he married Mathilde Marie Bloch on February 23, 1897 in Paris[15]. The couple had three children, two of whom were involved in the Resistance and died after being deported: Élie Victor (Le Havre 1899 – Sobibor 1943 [16]) and Mayer Maurice (Paris 1905 – Auschwitz 1942 [17]). Having established himself as a carpet merchant in Paris, Mardochée went bankrupt in 1909, then divorced in 1912, before getting remarried in 1914 in Marseille to a young Algerian woman: Emilie Mezltoub Saffar (Cherchell 1889 – Neuilly-sur-Marne 1935). Mardochée lived at ʺLe Cottageʺ in Nice, and he went on holiday to Aix-les-Bains [18], which suggests that he had a comfortable lifestyle.

Mordecai may have been a younger brother of Joseph. Might his move to France and his financial success have encouraged the family back in Tunisia to go elsewhere as well?

It was around 1907 when one of Félix’s sisters, Émilie, the first of the siblings, arrived in France with her husband Jacques Marzouk and their two children. Yet Jacques had a “good job” in Tunis: he was the head of the Employment Office at 12, rue de Rome, before he set himself up as a trader. We next come across him in 1908, when he was a perfume maker in Toulouse, where their daughter Germaine was born. The family then left for Belgium where they lived for a few years in Uccle, a suburb of Brussels [19]. Émilie and Jacques were both traders, as was noted on the birth certificate of their daughter, Caroline Stéphanie [20]. Then, in 1914, after the outbreak of the war, Emilie was evacuated from Brussels to Lyon, in the Rhone department of France[21]. Did her husband go to join her in Lyon? Or did they only get together again later on, in Paris?

In 1920, the siblings were all reunited in Paris, near their widowed mother, Esther. According to the Zirahs’ family memories, “they left because their house had been broken into”. Presumably, there were various reasons why the family left Tunisia: the death of the father, the departure of Émilie and her family in 1907, the desire to succeed, and also the pogroms in Sfax, Sousse and in the capital in 1918.

“On November 11, 1918, the population of Tunis celebrated the armistice. Little Victor [22] had gone to see the parade of flags when, all of a sudden, turbaned troublemakers threw to the vindictiveness of the crowd the closeted few, the profiteers who had grown fat while the others were fighting in Europe: the Jews. A pogrom broke out in the Jewish quarter and the child, terrorized, had to hide under his parents’ bed [23].”

In Paris, the two sons and their mother lived at 19, rue des Messageries, and then in 1921 they moved to 78, avenue Jean Jaurès. They were then joined by their first cousin, Simon Elhaïk [24], who started looking for a furnished room with meals provided [25].

It was a happy time. In 1922, Emilie and Jacques Marzouk’s daughter, Marcelle, “a slender, elegant brunette with long black eyes [26]”, was elected Carnival Queen of the 10th district of Paris, a fact reported by the Parisian press, as well as by the Annales coloniales (Colonial Gazette) in an entry with the catchy title ʺLa Tunisie conquiert Parisʺ (“Tunisia conquers Paris”), which was published on the front page [27]. One can imagine how delighted and proud the family was.

As the family grew up, new couples were formed. First, Élie Émile Zirah married Madeleine Bouchand (Puteaux 1901 – Bobigny 1998) on May 28, 1921 in Gagny [28], and then their cousin, Simon Elhaïk (Tunis 1894 – Paris 1989), married Marie Estrade on October 26, 1922 in Paris [29]. Félix Zirah went to both weddings.

Naturally, after that, new babies came along to brighten up Élie Émile and Madeleine’s household: Simone (Paris 1922 – Chartres 2021), Joseph Georges (Lyon 1923 – Montreuil 2017), Jean Roger (Bordeaux 1927 – Villevaudé 1985) and Marcel Eugène (Villemomble 1933 – Le Raincy 2008), and also that of Simon and Hélène: Jeannine (Paris 1924 – Saint-Maurice 2016) and Jacques David (Bordeaux 1928 – Paris 2012), plus, according to family memories, another child whose identity and birth records have never been found.

Élie Émile and his family [30]

The children’s birth towns reveal how much the fathers traveled, always in search of a good deal. The men of the family were initially second-hand and antique dealers, before setting themselves up as jewelers. For example, Félix’s brother-in-law, David Smadja, a jewelry dealer, had a store on the third floor of a building at 1, boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle in Paris. There he was attacked twice: first in February 1934 [31], and then in December 1937 [32], which caused a flurry of newspaper articles, even making the headlines with a photo on the front page: ʺJeweler attacked in his store… and his assailant goes missing between the scene of the drama and the police stationʺ, with more details on page 4.

David Smadja [33]

From junk dealer in Paris to jewelry broker in Lyon

In 1921, Félix Zirah was living with his mother at 78 avenue Jean Jaurès in the 19th district of Paris. He placed an advertisement announcing that he was looking for 2 rooms or 1 room and a hallway for use as an office [34], probably in which to set up his own business. The following year, on his cousin Simon Elhaïk’s marriage certificate, he is referred to as a second-hand dealer, living at 17, rue de Moscou in the 8th district. However, on October 31, 1922, he was sentenced to a 6-month suspended prison sentence and a 500-franc fine for handling stolen goods and contravening the laws relating to second-hand goods dealers. Was he too trusting, buying pieces without asking where they came from? Did he close his eyes to the provenance of the items? Or was he tricked? Either way, this negative experience prompted him to leave the capital for Lyon.

“The works of François Delpech[35] associates the pre-war Jewish population of Lyon with a Comtadine and Ashkenazi presence to which are added a few Sephardic families from North Africa. While the Jews from Morocco, who were less well-qualified, settled on the outskirts of the city, near the chemical factories, those from Algeria and Tunisia settled in the Presqu’île or on the slopes of the Croix-Rousse hill, close to the commercial activity that occupied them on a daily basis. Many were shopkeepers, peddlers, fairground vendors, second-hand dealers, etc.” [36]

Presumably, Félix, and subsequently his brother, were attracted by the many advantages that Lyon had to offer. Thanks to its rail network, it was a major transport hub and the second most important economic and trading center in France, after Paris. They were also attracted by the presence of Tunisian merchants, such as the Boccara family, who were already well-established in the vicinity of the Place Bellecour [37].

Félix quickly found his niche. In 1924, he went on vacation to the Grand Hôtel Cosmopolitain in Aix-les-Bains [38].

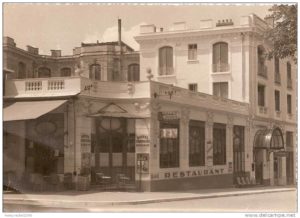

Grand Hôtel Cosmopolitain

In 1926, he was buying and selling precious materials. Shortly before his wedding, and also to have more flexibility in his business, he sold, “according to a private deed dated January 12, 1926 in Lyon […] his share in the right to the lease of a commercial space located in Paris, at 25, rue Bergère” [39] to his brother, Élie Émile, who was living at 36, rue de Dijon in Lyon, and to his cousin, Simon Elhaïk, who was living at 19, rue Margaux in Bordeaux. From that point on, Élie Émile and Simon went into business together: first in Bordeaux[40], where their brother-in-law Élie Émile Smadja sold them the right to lease premises at 42, cours de l’Intendance in Bordeaux (an upscale district of the city), and then in a “jewelry business located at 8, boulevard Montmartre in Paris; a limited liability company with a capital of 50,000 francs (50 shares of 1,000 francs). [41]”

A suspect stranger who became unwelcome

A few days later, on January 16, 1926 [42], in Lyon, Félix married Germaine Élise Pistré (Paris 1899 – Argenteuil 1982), whose parents were dead. The witnesses were Georges Brami [43], a student, and his wife, Suzanne Laurent. None of their family members appear to have attended the ceremony. Both were living at 32, rue Ferrandière, a street where many Jews from North Africa rented furnished apartments. At this address, he also had an office he called ʺLe Comptoir de l’Orʺ from which he ran his business; in 1926, under the name ʺSimonʺ, he opened an office at 1, place des Cordeliers. This office closed in September 1928. He employed one worker and a woman called Christé [44]. In the 1926 census, he was described as a second-hand dealer [45], but in 1929 he declared himself to be a “jewelry broker” [46] who made his living from this trade alone. These job titles clearly show that he was ambitious and wanted to climb the social ladder.

In a report dated September 26, 1926, the Special Commissioner of Bellegarde reported to the Lyon Security service “a suspicious couple who, while passing through Bellegarde, were carrying a small box containing jewelry. It was ZIRAH and his employee, a woman named Émilie Olga CHRISTE, 25 years old, of French nationality, who was said to be his concubine. ZIRAH stated that he was going to Geneva” [47].

He was a good-looking man who was “5’7″, with greying hair, an American-style beard, an oval face, and a matte complexion” [48]. Did his successful career and attractive appearance encourage him to have an affair with his employee? Or was this the beginning of a great romance?

Soon afterwards, the relationship between Félix and Germaine began to break down: following a non-reconciliation order in 1927, they separated in 1928 and were then divorced on April 19, 1929 in Lyon “to the sole detriment of the wife and in favor of the husband” [49].

In addition to the marital problems, there was another new lawsuit. On December 10, 1928, Félix was condemned by the Correctional Court of Lyon to a fine of 16 francs “for contravening the law of 19 Brumaire Year VI [50] and receiving stolen goods”, because he had bought some jewelry from a thief. From then on, he was listed as a “foreigner subject to deportation”. However, since this second conviction was for a minor offence, he was treated leniently on account of the information that had been collected about him.

“The information collected about this foreign citizen is not unfavorable. He has complied with the law and the decree relating to the stay of foreigners in France. I am of the opinion that there are no grounds for deportation of the above-mentioned person, but he should be warned that if, in the future, he commits another offence, this action will be taken against him” [51].

On April 19, 1929, the Secretary General of the Rhone Police sent the Minister of the Interior a thick file containing a briefing on Félix Zirah, a reminder of the facts and of the previous conviction, as well as a personal profile. He concluded his covering letter with these words: “This is why, although at present the information collected on this foreigner is not unfavorable, I believe that there are grounds for expelling the said ZIRAH” [52]. A week later, following on from this advisory, a deportation order was issued against Félix [53], on the grounds that “the presence of the above-mentioned foreigner on French territory is likely to be a threat to public safety” [54]. Felix was thus ordered to leave France.

Although exact figures for 1929 are not available, the 1931 census shows that 2,890,000 foreigners were living in France, that being almost 7% of the total population [55]. Nearly a million of them became French citizens by naturalization between 1921 and 1939 (mostly Italians, Poles, Spaniards, and Belgians), since, among other things, this meant that they could avoid being repatriated in the 1930s. However, although he was the husband of a French woman, Félix did not apply for French citizenship, so he remained a ʺTunisian under French protectionʺ. This hybrid ʺprotectedʺ status already existed in the context of the capitulation of the Ottoman Empire. It granted people who were not natives of the country the protection of the sultan or of a consul. After 1881, in the Regency of Tunis, a French Protectorate, a system of co-sovereignty prevailed, in which pre-colonial state entities were maintained. As a result, from the point of view of nationality law, France still considered Tunisia to be a foreign country, as the laws and jurisprudence on the subject made clear at the time. It was partly to resolve any conflicts of identity, which affected protected citizens in Europe, that Tunisian nationality was created in 1914 [56].

On May 2, 1929, the chief commissioner of the Lyon Security service served Félix Zirah with a deportation order, telling him that he had 20 days to leave the country and that he had to hand in his identity card. In France, in the period between the wars “The identity card is the most valuable asset of a foreigner living in France. Without one, he is breaking the law” [57], according to the two decrees of April 1917 by which the Ministry of the Interior required all foreigners living in France to carry an identity card. “Whether he was acting out of a deliberate desire to break or circumvent the rules, out of ignorance of the regulations in force, or out of a newfound desire to legalize his situation, the foreigner was henceforth subject to endless scrutiny” [58].

As soon as he was informed of this deportation order, Félix Zirah wrote to the Prefect to justify his actions and to deny any dishonesty. His letter showed him to be a thoughtful man.

“I was served with an expulsion order issued against me on April 27, 1929, following a very lenient sentence of a 16 Franc fine. Also, this offense was very odd, because although my ledger did not include the entry required by the law, it was noted that a draft entry showed the transaction, which I had made correctly. This was not an isolated case, as I had been in the habit of doing this for several years and I was able to produce thousands of similar draft entries to prove it.” [59]

Félix Zirah concluded by requesting temporary permission to remain in Lyon, which was granted on June 10, 1929, after a request from the Rhône deputy, Joanny Coponat, to the Ministry of the Interior. (One can only wonder on what basis Felix was able to benefit from the politician’s support). The Prefect of the Rhône was then informed that Félix Zirah was authorized, as from June 15, 1929 “to reside in France for three months on a trial basis and on condition that his conduct was beyond reproach” [60]. Félix was then advised to make a fresh request for a residence permit and to apply for a new identity card. Then, on September 7, the Minister of the Interior “authorizes the said Félix Zirah to reside in France on the basis of renewable quarterly extensions and on condition that his conduct is beyond reproach.” [61]. From then on, this became Felix’s normal administrative routine: 15 days before the end of each extension, he had to submit a new application for a residence permit and send in the receipt for his identity card application. Each time Felix sent in his application, the Chief Commissioner of the Security service informed the Secretary-General of the Police Department that Zirah’s circumstances had not changed and that “the information collected about this foreigner is all good.” Finally, on March 20, 1930, the Minister of the Interior authorized Félix to live in the Rhône department on the basis of renewable yearly extensions, again “on condition that his conduct is beyond reproach”.

Once his residency status was resolved, Félix got married for the second time. On July 22, 1930, in Lyon [62] he married Émilie Olga Christé, the young woman who had worked for him for several years.

Émilie Olga was born on March 17, 1905 in Villefranche-sur-Saône in the Rhône department. She was the daugher of François Emile Christé (Bassecourt 1875 – Villefranche? around 1923), a Swiss piano tuner, and Marie Marguerite Clerc (Tossiat 1888 – Lyon 1963), Swiss piano tuner, and Marie Marguerite Clerc (Tossiat 1888 – Lyon 1963), a tough woman who did not let the trials of life get her down. Émilie Olga was the oldest child, followed by Georges Émile (Saint-Etienne 1906 – Villefranche 1925), André Philippe (1910 – 1910 in the Rhône department), Louis Gustave (L’Arbresle 1914 – Lyon 1990), Eugénie Flavie (Lyon 1918 – Francheville 2003) and François Émile (Villefranche 1921 – Lyon 2016). Widowed with 6 children, probably in 1923, Marie Marguerite got remarried in 1924 [63] to Félix François Fournier, a tinsmith and then a sailor who was convicted in 1931 and 1934 “for fishing at night without permission”[64]. She had two sons with him: Antoine (Villefranche 1924 – Lyon 2010) and Jean Lucien (Villefranche 1927 – Tassin-la-Demi-Lune 2011). By 1931, the couple was separated and Marie Marguerite, who had become a laundry worker, was raising her children alone [65]. Émilie Olga must have remained very close to her family since she went to her sister Eugénie Flavie’s wedding in 1937 [66], and then that of her brother, Louis Gustave, in 1938 [67].

An interlude in Brussels

Félix precarious residency status continued until the end of the summer. On August 27, 1930, the chief commissioner of the Rhône Security service sent a long three-page letter to the Secretary-General of Police in Lyon, writing at the outset that “[…] according to the latest information received, this foreigner no longer deserves the benevolent arrangements that were made in his favor”[68]. And, to justify the fact that Félix Zirah was “unscrupulous in business matters”, he detailed two convictions and three untried counts of handling stolen property.

The first two were already known to the police. In 1925, on his instructions, according to the police, his employee Bramy, a Tunisian national, bought a ring for 6,500 francs offered to him by an underage girl, Jeanne Meunier, accompanied by a woman named Perret, both of whom were maids for a Mrs. Mathieu, from whom the ring, with a real value of 35,000 francs, had been stolen. Since Mrs. Mathieu did not follow up on her complaint, Zirah was not worried further.

On September 26, 1926, as we have seen, the Special Commissioner of Bellegarde reported to the Lyon Security service “a suspicious couple” [69] who were carrying a small box containing jewelry. Was this a case of Félix receiving stolen goods or was it that the police viewed him with suspicion? Either way, no legal action was taken.

The third accusation was much more serious. The Chief Commissioner of the Security service accused Felix of involvement in the Ennio De Renzi affair, which made headlines in 1928: “As De Ranzi was passing through Lyon, Zirah bought some jewels from him, which came from an assassination attempt followed by a robbery, which had taken place in Monte Carlo on August 4, 1928. 60,000 francs worth of jewelry had been stolen” [70].

“Lyon, August 22, morning newswire – The Lyon police have just arrested a dangerous criminal, the Italian Ennio de Renzi, born in Rome on January 27, 1893. De Renzi, an international swindler and skilled pickpocket, had previously been active in France, notably in Amiens and Nice” [71].

A reminder of what happened: De Renzi entered the Poutignat jewelry store in Nice, on the pretext of buying a ring; taking advantage of the fact that there were no other customers, he knocked out the saleswoman, Mrs. Ginguietti (or Ginginetti or Ginginette, according to the newspapers), and stole some jewelry. He then fled to Lyon where he sold some of it. Under police surveillance because he frequently changed hotels, he was promptly arrested and imprisoned pending his transfer to Nice, before being extradited to Monte Carlo.

“Lyon, August 23 – The Monaco judiciary telegrammed to request the extradition of the Italian Ennio de Renzi, who on August 5 had knocked out a jewelry store clerk in Monte Carlo and then stole 60,000 francs of jewelry. Most of the stolen jewels were found in shops on Lyon, to which de Renzi had sold them”[72].

This information was quickly relayed by other newspapers [73]. The courts convicted Ennio De Renzi and an accomplice, a man called Ricardo De Sienna[74], but Felix Zirah was never prosecuted. It seems clear, therefore, that the police blackened Felix’s character by attributing to him wrongdoings that he had not committed, in order to be able to deport him. The Chief Commissioner of the Security service concluded his letter by asking that the deportation order issued on April 27, 1929 be reinstated, since the presence of this foreigner in France should no longer be tolerated. The Prefect of the Rhône department promptly wrote to the Minister of the Interior, saying that, “according to the latest information gathered, this foreigner no longer deserves the benevolent treatment he has received” [75], and reiterating all of Felix’s real or supposed offenses, except for the Ennio De Renzi case. In short, in the tense political and social environment, with two convictions and above all suspicions of dishonesty, Felix had become “undesirable”.

“In a law thesis submitted in 1914 […], Georges Dallier thus called for vigorous measures to be taken against “undesirables”, whom he defined as follows: “[The undesirable foreigner] is not the placid, honest worker who respects the laws of police and security […] nor the tourist who contributes to general prosperity, nor the merchant who puts down roots in our country and whose interests become intertwined with ours. The ones we need to tackle are the undesirables […], the spies, the criminals, the vagabonds, the fraudsters, the inhabitants of tainted regions, etc., in short, the ones who cause trouble, who jeopardize our work and our security.” Protecting the French communities “invaded by this leprosy and which take on the aspect of a district of Warsaw or a suburb of Fez” thus appeared to him a matter of the utmost urgency” [76].

In accordance with the legislation of the time, but also out of mistrust, the Prefect concluded: “I believe that the presence in France of this foreigner, who is still engaging in shady deals, should no longer be tolerated” [77]. This was met with an immediate reaction: The Minister of the Interior ordered the Prefect of the Rhône department to reinstate immediately the expulsion order issued on April 27, 1929 against Félix.

The extensive administrative correspondence preserved in the Rhône departmental archives clearly shows how hastily the authorities arranged for Felix’s deportation; for example, a letter from the Chief Commissioner of the Lyon Security service mentions that Zirah had been asked to leave “our” territory within a period of 10 days expiring on September 28, that his permit had been withdrawn, that he was granted an additional period that would expire on October 20, and finally, that “the departure of this foreigner will be verified” [78].

Given that he no longer had an identity document or a residence permit, Félix had to apply for a passport to leave France with his wife. After the police investigated this request and issued a positive opinion, a passport with a limited validity from October 9 to 20, 1930, and with no right to re-entry into France, was issued to Félix Zirah on October 9. A French passport was issued to his wife, who remained a French citizen; “the man named Zirah made it known that he would be leaving for Belgium on October 17”[79]. The head of the Security service was charged with overseeing his departure.

Identity photos of Félix and Olga Zirah [80]

A few days later, Felix and Olga Zirah arrived in Belgium. They lived at 7, rue des Pierres in Brussels. We do not know if he worked or if he lived off his savings. Of course, the Belgian authorities were intrigued, perhaps even suspicious of this foreigner who had been expelled from France and asked for an explanation [81]. The interlude in Brussels ended on February 19, 1931 when Felix was allowed to stay for a month in the Seine department of France [82].

Although the police and the Security service in Lyon were informed of this, they became paranoid and searched for him in the capital of the Gauls (Lyon) and in the Rhône department. “In the event that this foreigner is discovered in Lyon, he should be asked to go to the Seine department within 24 hours, failing which he will be arrested for violating the deportation order issued against him” [83]. However, the search was fruitless, and the responses from the Lyon police were the same for months: “the man born Félix Zirah, of Tunisian nationality, who had been expelled from France, was searched for in vain” [84]. A final letter from the Chief Commissioner of the Security Department concludes the file: “Zirah was sought in vain, his mother-in-law, Mrs. Fournier, and his nephew, Mr. Bramy, have not had any news since his departure at the end of October 1930. Since December 1, Zirah has no longer had a mailbox at 32, rue Ferrandière in Lyon” [85].

Did this ordeal make Felix Zirah reconsider? Unlike those who to some extent consciously blot out their misdemeanors in order to preserve a good image of themselves, something scientists call “ethical amnesia,” Felix had no doubt turned his mind back to the events that led to his removal from France. From then on, he would live a very quiet life.

A quiet life in Paris

On March 4, 1931, having returned from Belgium, Félix moved to Paris. The Ministry of the Interior was approached by the Prefect of the Seine to ask him to make a decision about Félix, and also by Émilie Olga, who asked him renew her husband’s temporary residence permit. Three weeks later, Félix was notified that he had been granted a three-month residence permit. He was living at 40, rue Nollet, in the Batignolles area, and then at 13, rue du Maine in the 14th district of Paris, “where he and his wife lived in a room with a monthly rent of 230 francs, which was paid regularly” [86]. It was a small, three-story building with apartments and business premises on the ground floor. Félix worked as an auditor at a refrigeration company whose head office on rue d’Astorg in Paris.

On May 6, 1931, the International Colonial Exhibition opened in Paris. It was to attract nearly 8 million visitors who came to make ʺle tour du mondeʺ, or “a tour of the world”, as the slogan at the time put it. The Tunisian display at the Colonial Exhibition was kind of summary of indigenous life represented by an official building featuring Arab architecture, with adjoining souks, which were accurate reproductions of those in Tunis, with their craftsmen and stallholders. Might Felix have gone there out of curiosity or nostalgia for his native country?

In June 1933, Inspector Schwartz of the Seine Police Department sent a report to the Deputy Director, head of the Department for the Protection and Surveillance of North African Natives, in which he stated that Felix’s situation had not changed since April 1931 and that his character report was excellent. Aside from their personal attributes, Félix and Émilie Olga give the image of a close and united couple, despite the legal setbacks and the ups and downs of life.

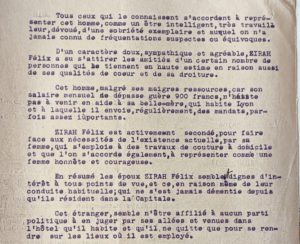

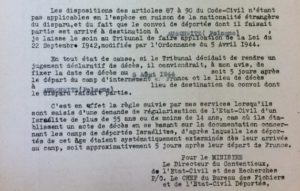

An extract from Inspector Schwartz’s report [87]

“The information gathered about this French-protected person being in his favor” [88], the deportation order was officially postponed in July 1933 [89] and Félix was notified on August 10. From then on, Félix and his wife led a quiet life, balancing work and family commitments. Their ties with the Christé family, who were still based in the Lyon area, continued, not only involving financial assistance, but also visits. For example, Émilie Olga was a witness at her sister Eugénie Flavie’s wedding in 1937 [90], and then, the following year, at that of her brother, Louis Gustave [91]. Although the Zirahs and their extended family (the Smadja, Marzouk and Elhaïk families) all lived in the Paris area, and it would seem that they saw each other sometimes, it is impossible to know how close they were because there are no family memories or marriage certificates. Apart from two of them, the next generation did not get married until after the war.

Félix and Émile Zirah’s family out for a walk [92]

War and family crises

On September 3, 1939, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany following its invasion of Poland. However, no major battles took place in Western Europe; for months, French soldiers waited, stationed behind the Maginot Line. The “phony war” ended on May 10, 1940, when Germany decided to infringe on Belgian and Dutch neutrality to enter France. On May 28, Belgium was conquered. The “great exodus” drove the Belgians and then the French onto the roads, including two thirds of the Parisians, i.e. about 2 million women, men and children.

Confronted with the advance of German troops, General Pierre Hering, the military governor of Paris, stated on June 11, 1940, that the capital had been declared an open city, deeming it unnecessary to defend Paris militarily. On June 14, German troops arrived in Paris, which then ceased to be the country’s capital and became the headquarters of the German military command in France, involving a significant number of enemy troops and personnel.

“In the summer of 1940, the French were not looking ahead to the four years they were going to experience. The occupation did not begin with Oradour-sur-Glane. […] The occupation was a test of the whole of French society. It gave rise to contrasting reactions, and also to vague, uncertain, ambivalent attitudes. No one was exempt from making a choice” [93].

While most of the family stayed in Paris, a few left the capital, including Élie Émile Zirah, Madeleine and their children:

“During the war they went down to the South of France for the summer; my grandfather Georges caught typhus and they extended their stay due to that. Madeleine went back up to get winter clothes and realized that it was better to stay there. They stayed hidden in Pau until the liberation” [94].

Left behind with no news, the ʺParisiansʺ were worried. Their nephew, Maurice, made an appeal in a daily newspaper, “To get in touch with refugees: MARZOUK Maurice, 11 boulevard Port-Royal in Paris” [95].

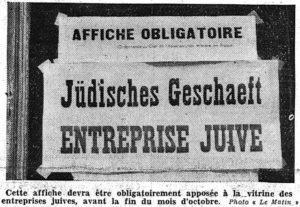

After the debacle of May-June 1940, full authority was given to Marshall Pétain. The Vichy government soon introduced anti-Jewish legislation. State anti-Semitism, which accused the Jews of all kinds of evils, was initially a matter of exclusion and appropriation of property. On October 3, 1940, the Vichy government enacted the first Statute of the Jews and began the policy of economic Aryanization. The spoliation process put in place by the Nazis was supported by the Vichy government: to determine who was a Jew and to organize a census of Jews, in order to better prohibit them from their professional activities and ultimately to rob them by confiscating their businesses and then liquidating or selling them. The process was based on a series of German orders (September 27, 1940 and April 26, 1941) as well as the French law of June 2, 1941. Very quickly, in less than a year, the legal framework was in place to eliminate any Jewish involvement in the French economy.

A sign saying “Jewish business” [96]

Simon Elhaik was a victim of the spoliation policy: in 1941, André Verdier, a chartered accountant, was appointed provisional administrator of the watchmaking, jewelry and optical business located at 50, rue Lecourbe in Paris (which Simon had bought in 1933 when he left Bordeaux) [97]) which he sold in 1943 to Mrs. Yvonne Louise Jollain, a jeweler and the wife of Léon Jean Victorin Rossat [98]. Simon’s nephew, Georges Brami, also had his business Comptoir des perles et métaux précieux (Pearls and precious Metals counter) at 95, rue de l’Hôtel-de-Ville, sold by Mr. Madignier, an administrator/liquidator, according to a Commercial Court judgement dated June 1, 1942 [99].

The year 1941 should have brought a little cheer, as Emilie Olga was expecting a baby. Sadly, however, she died on July 26[100] in the Cochin Hospital on boulevard Port-Royal in Paris, after giving birth to little Olga Tita Rose. The baby did not survive and died on November 9 at her father’s home at 25, cours Suchet [101].

Félix’s various addresses during this period show how often he moved, no doubt to conceal his whereabouts out of fear of roundups or being turned in. The Occupation generated an atmosphere of terror in Paris. Anti-Semitism was intensified by the Vichy laws, collaboration and a widespread climate of hatred of “Others”: communists, freemasons, gypsies etc. and of course Jews!

Created in March 1941 by the Vichy government, at the behest of the SD (Gestapo) and the German Embassy in Paris, the General Commissariat for Jewish Questions (C.G.Q.J. ) was intended to perform two main tasks, according to Hannecker [102]: “on the one hand “the management and steering of a purely French Institute for the study of Jewish influence,” […] and on the other hand “the shaping of anti-Jewish propaganda, according to the principles which are important within the framework of the overall plan and determined, in turn, by the overall work of the Jewish Office.”[103]

Organized by the Germans and the IEQJ (Institut d’étude des questions juives, or Institute for Jewish Studies), the exhibition ʺLe Juif et la Franceʺ (The Jew and Franceʺ), which opened on September 5, 1941, was intended to inform Parisians about “the Jewish race,” the French Statute of the Jews of October 3, 1940, and the German ordinance of April 26, 1941, which might otherwise have seemed too theoretical. Putting images to words was much more effective. “For each of these subjects,” says the exhibition program, “a Jew (with the distinctive features of his race) is shown in drawings or enlarged photographs with text relating to them. Supporting evidence, letters, newspapers, books, photos, original documents are added.” [104]

Poster for “The Jew and France” exhibition on the wall of the Palais Berlitz [105]

“In the medium term, the exhibition would like to prepare French public opinion for the extermination of the Jewish population.”[106] The exhibition ended on January 15, 1942, later than scheduled, so that people from the provinces who had come to Paris during the holidays could visit it and “learn about the Jewish issue.”[107] However, in spite of massive publicity, the exhibition does not seem to have been as successful as expected.

1942 was a turning point in France. Jews had to wear the yellow star and roundups and deportations became more widespread.

On March 27, 1942, the first transport of Jewish deportees, Convoy 1, left France for the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in Hitler-occupied Poland, carrying 1,112 men in all. Only 19 of them survived and came back after the war [108].

On July 16 and 17, 1942, the Vél’ d’hiv’ roundup took place, followed in the next few months by roundups in Périgueux, Limoges, the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region and other areas.

The Zirah family did not escape the roundups [109]. On September 21, 1942, David Smadja, one of Félix Zirah’s brothers-in-law, was deported from Pithiviers camp on Convoy 35 and executed upon arrival at Auschwitz. In 1943, the Marzouk family was also involved: Wanda Schlesinger [110] and her daughter Francine Taïta Marzouk [111] were arrested, interned in Drancy and deported on Convoy 62 on November 20, 1943 to Auschwitz, from which they never returned.

At what point did Felix decide to seek refuge in Lyon? After grieving? After the Vél’ d’hiv’ roundup? After David Smadja was arrested?

A refugee in Lyon

Lyon and the surrounding area were exceptional during the Second World War, not only because they were in the so-called free zone until the end of 1942, and because Lyon was named the capital of the Resistance, but above all because the area was considered to be a safe haven for people threatened by the Nazis, especially Jews from Eastern and Northern Europe, who believed that they would find a safe and secure environment there.

In accordance with the two decrees on the status of the Jews, the Vichy government began arresting Jews in the southern zone. In doing so, it anticipated the demands of the occupying forces by participating directly in the deportation of Jews.

On August 20, 1942, Lyon was the setting for a round-up of foreign Jewish refugees [112], organized by the Vichy regime, an episode little known to the public, following the Vel d’hiv roundup in Paris. 545 people were arrested and deported. On September 5, 1942, Cardinal Gerlier published a pastoral letter in which he denounced the persecution of the Jews. The head of the Gestapo, Klaus Barbie, led the crackdown on the Resistance and the Jews, and the number of people arrested and deported in the region continued to increase as of 1943.

“We are all hopeful that the war will end soon. The Allies and their fleet have been advancing on the beaches of Normandy since June 6, 1944.” [113]

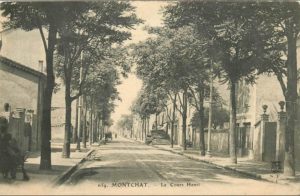

Félix Zirah did not have time to celebrate, however. He was “arrested by the Gestapo at his home on the morning of June 7, 1944,” at 147, cours Henri, in the Montchat district of Lyon [114].

Cours Henri in Lyon

Why was he arrested in this quiet neighborhood? Was he reported? Was it on account of his record as a foreigner who was already known to the police and the Security service? Was it because the identification system for foreigners, which included registration of their personal data and required them carry an identity card led to a system of cross-checks that focused on their civil and economic status as much as on political activity? “The police operation to register foreigners in France led, at the end of the 1930s, to the development of an apparently powerful framework of central services and peripheral offices that ensured a country-wide coverage. […] In 1939, the foreigners’ department of the Ministry of the Interior was responsible for managing 4,000,000 dossiers and 7,000,000 record cards.[115]

This highly bureaucratic supervision of foreigners led to the compilation of detailed dossiers, which the Gestapo discovered and used as soon as it became operational in occupied France. In addition, a “Fichier des juifs” (register of Jews) was kept in each prefecture from September 27, 1940 onwards. This means that there was no lack of sources of information.

Félix Zirah was imprisoned from June 7, 1944 to July 1, 1944 in the Fort de Montluc in Lyon [116], and then transferred to Drancy camp [117]. The Carnet de fouille (search log book) N°153 states that he had a gold ring with a stone, confirmed by receipt N°6141. His last known legal address was 6, place de la Madeleine, in the 8th district of Lyon.

Solitude in the midst of the crowd

In Drancy camp, Félix probably felt very alone in the midst of this overwhelmed, desperate crowd. The voices, the moans, the cries reached him from afar. He was numb and powerless. This was a place where the meaning of the verb “to be able” was forgotten. People were hardly able to do anything.

On July 31, 1944, he was deported on Convoy 77 to Auschwitz, as the original deportation list confirms.

“A convoy to hell, and it was already hell on the train.” [118]

When he arrived at Auschwitz, he was probably selected for the gas chambers, given his age and his weary, perhaps even apathetic, state.

Photo taken on May 27, 1944 showing Nazis selecting passengers as they arrived in Auschwitz

(Yad Vashem Archives/AFP) [119]

“In the spring of 1944, the camp authorities had decided to extend the unloading ramp for the convoys to bring it closer to the gas chambers. […] We were getting used to the appalling atmosphere that reigned in the camp, the stench of the burned bodies, the smoke that obscured the sky, the mud everywhere, the penetrating humidity of the marshes. […] A terrible sadness gripped me when I saw, scattered on the ground, the clothes of people who had just been gassed.” [120]

Felix Zirah was later declared to have died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland) [121] according to an arbitrary method put in place due to the lack of records, which was the system in effect at the time.

Extract from a letter from the Ministry certifying the date of death [122]

“No one remembers him, or even having seen him.”

Did his brother and family members search for him? Were they among those who pressed for information at the Hotel Lutetia, which had been turned into a reception center for survivors? Were they among those who tried to glean information from the surviving deportees who had just come back?

Only one notice was published in the press, by Élie Smadja, who had no news of his father.

DEPORTED, REPATRIATED [people]

I would be grateful to anyone for.

providing info. concerning David

SMADJA, deported on 29-2-42 from

Pithiviers bound for Metz

Write to Elie Smadja, 23, Bd Italiens [123]

Since Félix was still Tunisian, the family did not apply for any special status for him, but just to settle his estate. Maurice Mazouz, his nephew, began the formalities on May 8, 1948, with a request for the civil status of “non-returnee”. On August 28, 1948, a disappeared person’s certificate for Felix was issued and sent to the family’s attorney, Colette Hauser. Next, although she had the disappeared person’s certificate, she needed a birth certificate in order to obtain the death certificate, as required by the public prosecutor’s office of the Seine department. However, the research proved difficult, because “nobody remembers him, nor even having seen him” [124]. After various exchanges of letters between the public prosecutor and the Minister of Veterans and Victims of War, following a request by an attorney called Houssard for a death certificate, the Seine Court declared the death “valid” in a judgment dated July 22, 1949. In January 1950, it was transcribed into the civil status registers of the 8th district of Paris.

In Memorium

A book that contained a life has opened and closed.

The name of Felix Zirah is now inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris: slab 43, column 15, row 1 [125].

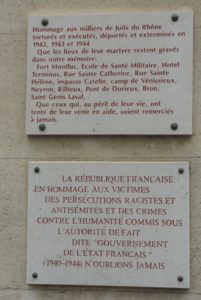

In Lyon, two memorial plaques commemorate the persecution of the Jews:

Center National de la Résistance et de la Déportation (National Center for the Resistance and Deportation): remembering anti-Semitic persecution [126].

References

[1] Rachel Franco, ʺAuschwitz : le mot impossibleʺ, http://awans-memoire-et-vigilance.over-blog.com/2019/04/auschwitz-le-mot-impossible-poeme-de-rachel-franco.html

[2] The following biographies have been written: Danielle Laguillon Hentati: “In Memory of Dario Boccara”: http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/dario-boccara/; “The journey with no return of Abraham Albert Boucara”: http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/abraham-boucara/; “The shattered life of Laure Cohen”, http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/laure-cohen-nee-taieb/; “From Tunis to Auschwitz: the journey of Gaston David Nataf”: https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/gaston-nataf/ ; “Gerlys will never danse again, he did not hold onto his life: Biography of Gaston Secnazi”: https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/gaston-secnazi/ ; “The unfinished life of Élie Gaston Setbon”: https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/elie-setbon/. The last 3 are currently under review.

[3] Dossier ZIRAH Félix DAVCC MED 21 P 552 397, 19 p.

[4] Rhône departmental archives, Fort Montluc; Mémorial de la Shoah, Fiche ZIRAH from Drancy. Site de Yad Vashem: https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr

[5] French National Archives – Pierrefitte, Inventory of the individuals of the Central File of the National Security service, Period: 1890 – 1940, Dossier ZIRAH Félix (1929-1933), Record 19940488/64, File sequence number _z_5569, order number 5538. Digital photos taken by Séverine Zirah, to whom I am very grateful. The dossier AN ZIRAH Félix includes two dossiers, namely that of the expulsion order of April 27, 1929 Notified on May 21, 1929 in Lyon State 662, plus that of the reported order of the Directorate of General Security – Judicial Police of July 18, 1933 State 711. It is a collection of administrative letters, minutes and notes, as well as the two decrees pronouncing the first the expulsion and the second the withdrawal of the expulsion order, as well as a letter from Félix Zirah. These documents date from April 19, 1929 to August 22, 1933, and originate from police departments, the North African Indigenous Affairs Department – General Security 2nd Office, the prefectures of the Rhône and the Seine, the Ministry of the Interior in Paris and the Ministry of Justice in Brussels.

[6] Rhône departmental archives, Foreign Nationals Monitoring, ZIRAH Félix file, reference 3494W33, file 14811 DE. I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to Séverine Benture who, after some research, found this file and sent me a scanned copy. This file is made up of letters and notes between the Prefecture of the Rhone, 4th Division, 3rd Office, and the chief police station in Lyon, from March 20, 1929 (when Félix Zirah was liable to expulsion from French territory) to January 15, 1932 (when the search for him in Lyon and the Rhone stopped). It also contains Félix Zirah’s requests for a stay of execution, his applications for a foreigner’s identity card and the related receipts, as well as his applications for a French passport for himself and his wife to travel to Belgium.

[7] She was Simone Zirah (1922-2021), a daughter of Élie Émile and therefore Félix’s niece.

[8] Information provided by Moché Uzanthe, deputy of the Chief Rabbi of Tunis.

[9] La Dépêche tunisienne 1897/11/15, p.4.

[10] Religious marriage certificate (ketouba) from the great rabbinate of Tunisia.

[11] Hagege Family tree, extended family: https://gw.geneanet.org/claudio75017?n=setruck&oc=&p=albert+francois

[12] The declarations of birth and death of Tunisian subjects, Muslims and Israelites, became compulsory after the Tunisian decree of December 28, 1908 (JORF dated 30/12/1908 – p. 1183).

[13] The name of this neighborhood comes from a railroad crossing that used to be located there.

[14] Claude Hagège, Bernard Zarca, ʺLes Juifs et la France en Tunisie. Les bénéfices d’une relation triangulaireʺ, La Découverte | « Le Mouvement Social » 2001/4 no 197 | pages 9 à 28, https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-mouvement-social1-2001-4-page-9.htm

[15] Municipal archives of the 10th district of Paris, marriage certificate N°229.

[16] Mémorial de la Shoah : https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=noms_tous%3A%28zirah%29%20AND%20id_pers%3A%28%2A%29&spec_expand=1&start=0

[17] Mémorial de la Shoah : https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=noms_tous%3A%28zirah%29%20AND%20id_pers%3A%28%2A%29&start=2&rows=1&fq=diffusion%3A%28%5B4%20TO%204%5D%29&from=resultat&sort_define=&sort_order=&rows=

[18] Bulletin des étrangers en séjour à Aix-les-Bains (Newsletter for foreigners staying in Aix-les-Bains: official alphabetical list / published under the patronage of the Hoteliers’ Association of Aix-les-Bains [“later” of Aix-les-Bains, the Savoie and the South-East] 1923/07/10, p.4.

[19] Information provided by Olivier Croon, administrative secretary at the Population Service in Uccle.

[20] Belgium, Uccle, Population Service, 1910, birth certificate n°277 with no special annotation.

[21] Report on the current residence of evacuees from Belgium, fasc.1 / Ministry of the Interior. Directorate of General Security, 1914, Liste 4 p. 102.

[22] This was Messaoud Hai Victor Perez, (Tunis 1911 – Gliwice 1945), a famous Tunisian boxer who went by the name of Young Perez.

[23] M. Leroy, Recension de Young : https://www.bdgest.com/chronique-5890-BD-Young-Young.html

[24] Simon was the son of David El Haïk and Allegra Zirah, a sister of Joseph Zirah.

[25] Le Journal 1921/04/20, p.4.

[26] ʺLes reines de Paris. Le 10° arrondissement élit une sténographeʺ, Le Journal 13/02/1922, p. 1.

[27] Les Annales coloniales 1922/02/13.

[28] Gagny town hall, marriage certificate n°30.

[29] Municipal Archives of the 9th district of Paris, marriage certificate n°1513.

[30] Family archives provided by Séverine Zirah.

[31] ʺUN BIJOUTIER attaqué dans son magasin par un client mécontentʺ, Le Journal 1934/02/22, p.

[32] ʺL’agression contre le bijoutier du boulevard Bonne-Nouvelleʺ, Le Journal 1937/12/28, p.1, 4 ; ʺBoulevard Bonne-Nouvelle – Un bijoutier est assailli par un soi-disant client – Quoique blessé il met son agresseur en fuiteʺ, Le Populaire 1937/12/28, p.3 ; voir également un entrefilet dans Le Temps 1937/12/29, p. 4, et Le Populaire du Centre 1937/12/29, p. 2.

[33] Le Journal 1937/12/28, p.1.

[34] Le Journal 1921/09/20, p.4.

[35] François Delpech, Sur les Juifs : Études d’histoire contemporaine, Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1984, p. 147-159. Cité par Sylvie Altar, ʺLes Juifs du Maghreb à Lyon (1900-1945)ʺ, dans Archives juives 2020/1 (Vol 53), p. 18.

[36] Sylvie Altar, ʺLes Juifs du Maghreb à Lyon (1900-1945)ʺ, op. cit.

[37] Danielle Laguillon Hentati, “Le voyage sans retour d’Abraham Albert Boucara”, op. cit.

[38] Bulletin des étrangers en séjour à Aix-les-Bains (Newsletter for foreigners staying in Aix-les-Bains: official alphabetical list / published under the patronage of the Hoteliers’ Association of Aix-les-Bains [“later” of Aix-les-Bains, the Savoie and the South-East] 1924/07/27, p.8.

[39] https://www.retronews.fr/journal/la-loi/01-fevrier-1926/1703/3740951/

[40] Archives commerciales de la France : Journal hebdomadaire, 1926/02/20, p. 456.

[41] Announcement published in Le Courrier. Previously the Guide du commerce et Courrier des hôtels [“then” Journal quotidien, Feuille officielle d’annonces légales et judiciaires]… 1929/12/14

[42] Municipal Archives of the 2nd district of Lyon, marriage certificate n°25 with annotation mentioning divorce.

[43] Brami or Bramy appears later, in police reports, as a nephew of Félix.

[44] Letter dated March 20, 1929 from the General Secretariat of the Police – Subject: Foreigner liable to expulsion ZIRAH Félix, to the head of the Security service. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[45] Rhône departmental archives, 1926 census of Lyon: https://archives.rhone.fr/ark:/28729/gsl02b7kh5cq/30db7b0b-17ab-42f1-a442-87a65ef0367b

[46] Letter from Félix Zirah dated September 3, 1929, to the Minister of the Interior. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[47] Correspondence from the delegated Prefecture Councilor, addressed on September 2, 1930 to the Minister of the Interior, Directorate of National Security, 2nd office. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[48] French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[49] Municipal Archives of the 2nd district of Lyon, transcription n°149 of the divorce judgement.

[50] Law of 19 brumaire year VI (9 novembre 1797) relating to the supervision of title and the collection of security rights for gold and silver materials and articles: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/1797/11/09/n1/jo

[51] Reply from the Chief of the Security Service dated April 3, 1929 to the letter of March 20, 1929 addressed to him by the General Secretariat of the Police. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[52] Letter dated April 19, 1929 from the Secretary General for the Police for the Prefect of the Rhône to the Minister of the Interior. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[53] Expulsion order issued by the Minister of the Interior on April 27, 1929 in Paris. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[54] Expulsion order issued by the Minister of the Interior on April 27, 1929 in Paris. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[55] Statistique générale de la France, Résultats statistiques des recensements généraux de la population française de 1931, vol. « Étrangers et naturalisés, Division de la statistique générale », Paris, Imprimerie nationale.

[56] Décret beylical du 19 juin 1914 qui « pose les bases de la nationalité tunisienne. Un deuxième décret qui va dans le même sens voit le jour en 1921 (El-Ghoul, 2009 : 17-18). » Note 6, in : Fatma Ben Slimane, « Définir ce qu’est être Tunisien. Litiges autour de la nationalité de Nessim Scemama (1873-1881) », Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée [En ligne], 137 | mai 2015, mis en ligne le 16 juin 2015, consulté le 12 novembre 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remmm/9005 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/remmm.9005

[57] Arthur Koestler, La lie de la terre (1941), trad. Jeanne Terracini, Paris, Calmann-Lévy / Le livre de poche, 1971, p. 215.

[58] Ilsen About, ʺIdentifier les étrangers. Genèses d’une police bureaucratique de l’immigration dans la France de l’entre-deux-guerresʺ, p. 127-128. Gérard Noiriel. L’identification des personnes. Genèse d’un travail d’État, Belin, pp.125-160, 2007, 978-2-7011-4687-4. ⟨hal-02529432⟩

[59] Handwritten letter (arrived May 27, 1929) from Félix Zirah to the Prefect of the Rhône. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[60] Note dated June 10, 1929 from the Minister of the Interior to the Prefect of the Rhône. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[61] Letter dated September 7, 1929 from the deputy director in charge of the 2nd office, for the director of General Security service, for the Minister of the Interior, to the prefect of the Rhône. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[62] Municipal Archives de Lyon 2°, marriage certificate n°332.

[63] Family tree of Chantal Fournier, née Cormier: https://gw.geneanet.org/bassu?lang=fr&pz=chantal+madeleine+theodora&nz=cormier&p=marie+marguerite&n=clerc

[64] Rhône departmental archives, classe 1908, FOURNIER Félix François registration card n°170.

[65]Rhône departmental archives, Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon 10 rue Parmentier, 1931 and 1936 censuses, in which she is even referred to as “widow Christé”.

[66] Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon town hall, marriage certificate n°5 Raymond Joseph Lardaud – Eugénie Flavie Christé.

[67] Municipal Archives of the 2nd district of Lyon, marriage certificate n°54 Louis Gustave Christé – Rose Julien.

[68] Letter dated August 27, 1930 from the Chief Commissioner of the Rhone Security to the Secretary General of the Police in Lyon. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

— In May and November 1938, the Daladier government published decrees distinguishing between “healthy and industrious parts of the foreign population” and “morally dubious individuals, unworthy of our hospitality”.

[69] Correspondence from the delegated prefecture councilor, dated September 2, 1930, addressed to the Minister of the Interior, Directorate of National Security, 2nd office. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[70] Letter dated August 27, 1930 from the Chief Commissioner of the Rhone Security service to the Secretary General of the Police in Lyon. Rhône departmental archives ZIRAH Félix dossier n°14811 DE.

[71] ʺOn arrête à Lyon un dangereux malfaiteur internationalʺ, Le Matin : derniers télégrammes de la nuit 1928/08/23, p. 2.

[72] L’Oeuvre 1928/08/24, p. 4.

[73] Le Petit Provençal et L’Oeuvre 1928/08/23, then L’Ouest-Éclair, Le Petit Courrier, Le Petit Dauphinois 1928/08/29: de Renzi was going to be transferred to Nice to be questioned about the robbery of the Hotel des Postes, committed during the night of August 2 to 3, 1928.

[74] Ricardo De Sienna, born in Turin in 1892, was a former officer of the Italian Royal Navy, in ʺDe Renzi, le cambrioleur de la bijouterie Poutignat, n’en était pas à son coup d’essaiʺ, Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire 1928/08/29 p. 6. Voir également: ʺLes exploits du cambrioleur Ennio de Renziʺ, L’œuvre 1928/08/29 p. 4.

[75] Letter dated September 2, 1930 from the Prefect of the Rhône to the Minister of the Interior. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[76] Emmanuel Blanchard. Les ”indésirables”. Passé et présent d’une catégorie d’action publique. GISTI. Figures de l’étranger. Quelles représentations pour quelles politiques ? GISTI, pp.16-26, 2013. hal-00826717, p. 17-18.

[77] Letter dated September 2, 1930 from the Prefect of the Rhône to the Minister of the Interior. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[78] Letter dated September 22, 1930 from the Chief Commissioner of Lyon Security service to the Secretary General for the Police 4th Division 3rd Office in Lyon. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix, dossier n°14811 DE.

[79] Note dated October 10, 1930 from the Secretary General for the Police of the Rhône Prefecture to the Chief of the Security service in Lyon. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix, dossier n°14811 DE.

[80] Portrait photos taken for the passport application. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix, dossier n°14811 DE.

[81] Letter from the Ministry of Justice, Administrator of Public Security, addressed on December 12, 1930 to the Controller General of the Judicial Research Department, Ministry of the Interior in Paris. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[82] Handwritten note from the Ministry of the Interior for notification to Felix Zirah via the Minister of Foreign Affairs. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[83] Note dated March 2, 1931 from the Secretary General for Police of the Rhone Prefecture to the Chief of the Security service in Lyon. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix, dossier n°14811 DE.

[84] Letter dated March 18, 1931 from the Chief Commissioner of the Lyon Security service to the Secretary General of the Lyon Police. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix, dossier n°14811 DE.

[85] Letter dated January 15, 1932 from the Chief Commissioner of the Security service to the Secretary General for the Police 4° Division 3° Office in Lyon. Rhône departmental archives, ZIRAH Félix, dossier n°14811 DE

[86] Report dated June 23, 1933 from Inspector SCHWARTZ (Seine Police Headquarters, Protection and Surveillance of North African Natives) to the Deputy Director, Head of the Service. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[87] Schwartz report, French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[88] Letter from the head of the North African Affairs Department (for the Prefect of Police) addressed to the Minister of the Interior on June 30, 1933. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[89] The draft withdrawal of the expulsion order was written on July 18, 1933, but, curiously, the order postponing the expulsion measure bears no date. French National archives, dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[90] Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon town hall, marriage certificate n°5 of Raymond Joseph Lardaud – Eugénie Flavie Christé

[91] Municipal Archives of the 2nd district of Lyon, marriage certificate n°54 of Louis Gustave Christé – Rose Julien.

[92] Séverine Zirah’s family archives.

[93] Philippe Burrin, La France à l’heure allemande, Éditions du Seuil, Paris, janvier 1995, p.10.

[94] Testimony of their great-granddaughter, Séverine Zirah.

[95] Le Journal 1940/07/05, p.2.

[96] Excerpt from the newspaper Le Matin of October 19, 1940• Crédits: © gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

[97] Archives commerciales de la France: weekly newspaper, Sale of goodwill of the business. Table of business sales published from October 21 to 23, 1933, 1933/10/25, p. 4835.

[98] La loi 1943/04/10, p. 78.

[99] Le Salut Public 1942/06/26, p. 2.

[100] Municipal Archives of the 14th district of Paris, death certificate n°4443.

[101] Municipal Archives of the 2nd district of Paris, death certificate n°746.

[102] Theodor Dannecker (Tübingen 1913 – Bad Tölz 1945) was an SS-Hauptsturmführer. From September 1940 to August 1942, he managed the Nazi counter-espionage service at the SD office in Paris; he then held equivalent positions in other countries of Central and Southern Europe, specializing in the organization of the deportation of Jews in order to exterminate them.

[103] Joseph Billig, ʺLa naissance de l’Institut d’Études des Questions Juivesʺ, Le Monde Juif, n°59, 1970, p. 6-20 : https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-monde-juif-1970-3-page-6.html

[104] André Kaspi, “Le Juif et la France” (the Jew and France), an exhibition in Paris in 1941, Le Monde juif, no 79, 1975, p. 8–20: https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-monde-juif-1975-3-page-8.htm

[105] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1975-041-07,_Paris,_Propaganda_gegen_Juden.jpg

[106] André Kaspi, « “Le Juif et la France”, (the Jew and France), an exhibition in Paris in 1941, op. cit.

[107] Sézille to Von Valtier, December 8, 1941. C.D.J.C., XI – 103, cited by André Kaspi in, “Le Juif et la France”, (the Jew and France), an exhibition in Paris in 1941, op. cit.

[108] see: Antoine Fouchet, ʺRescapés du premier convoi de juifs pour Auschwitz-Birkenau, ils témoignentʺ, La Croix 2012/03/26: https://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.la-croix.com%2FActualite%2FFrance%2FRescapes-du-premier-convoi-de-juifs-pour-Auschwitz-Birkenau-ils-temoignent-_NG_-2012-03-27-782316#federation=archive.wikiwix.com

[109] We should also mention Marcel Léon Fischer, husband of Caroline Stéphanie Marzouk, who was the daughter of Jacques and Émilie Zirah. Marcel Léon was a draftsman at the Avionex factory and a member of the FFI (Forces françaises de l’intérieur, or French Resistance Army). Accused of having communicated the plans of his factory, he was shot by the Gestapo at the Balard shooting range in Paris on October 21, 1942. He is buried in the “carré des fusillés” (“plot for those shot”) of the cemetery in Clichy-la-Garenne.

[110] Wanda Schlesinger, wife of Joseph Marzouk: https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=noms_tous%3A%28MARZOUK%29%20AND%20id_pers%3A%28%2A%29&start=1&rows=1&fq=diffusion%3A%28%5B4%20TO%204%5D%29&from=resultat&sort_define=&sort_order=&rows=

[111] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=noms_tous%3A%28MARZOUK%29%20AND%20id_pers%3A%28%2A%29&spec_expand=1&start=0

[112] See for example: Témoignages sur la rafle de Lyon de 1942 (Testimonies on the roundup in Lyon in 1942): https://fresques.ina.fr/rhone-alpes/fiche-media/Rhonal00401/temoignages-sur-la-rafle-de-lyon-de-1942.html

[113] Jackie Pouzin, Parcours d’un déporté. Abraham Fridman (31 juillet 1944 – 1er mai 1945), 17 février 2020 : https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/28e121cc9067490a954ab5d270b4cb0c

[114] Information sheet from the Fort de Montluc [prison]

[115] Ilsen About, ʺEnregistrer et identifier les étrangers en France, 1880-1940ʺ : https://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.histoire-immigration.fr%2Fdossiers-thematiques%2Fintegration-et-xenophobie%2Fenregistrer-et-identifier-les-etrangers-en-france

[116] Fort de Montluc, file ZIRAH : https://archives.rhone.fr/ark:/28729/lmn654bk87wt/90e25da9-ee16-4ab2-adc5-12a9a566b087

[117] Mémorial de la Shoah, file ZIRAH : https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=identifiant_origine%3A%28FRMEMSH0408707144284%29

[118] Jackie Pouzin, Parcours d’un déporté Abraham Fridman (31 juillet 1944 – 1er mai 1945) https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/28e121cc9067490a954ab5d270b4cb0c

[119] Ginette Kolinka, “J’ai été déportée à Auschwitz : la moindre imperfection conduisait à la chambre à gaz”, Nouvel Obs 27-01-2015: https://leplus.nouvelobs.com/contribution/1313086-a-19-ans-j-ai-ete-deportee-au-camp-d-auschwitz-je-n-en-ai-pas-parle-pendant-40-ans.html

[120] Excerpts from: Simone Veil, Une jeunesse au temps de la Shoah, 2017.

[121] Municipal Archives of the 8th district of Paris: transcription of the declaration of death.

[122] DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen) Dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[123] Ce soir : grand quotidien d’information indépendant 1945/05/20, p. 2.

[124] Non-returnee information sheet. DAVCC Dossier ZIRAH Félix.

[125] Mémorial de la Shoah : https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=identifiant_origine%3A%28FRMEMSH0408707144284%29

[126] Par Olevy — personal research, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10942267

Français

Français Polski

Polski