Biography of Francis REISS

–

–

–

–

–

Francis Reiss’s identity card photo, 1960

Francis REISS was born on February 13, 1917 in the Caudéran quarter in Bordeaux.

He was the son of Jérôme REISS, born in New York and descended from a Jewish family from Manheim, and Léa ROSENFELD, who was born in Bordeaux.

His father founded CRESCA – Reiss and Brady, an import and export company dealing in luxury groceries in Bordeaux, along with its counterpart Brady, in New York.

His family lived at 7, rue du Bosquet, in Caudéran, a town in the suburbs of Bordeaux.

After attending Montesquieu High School, Francis studied law in Bordeaux (1936) and then in Paris (1937-1939) where he also studied at the Ecole de Sciences Politiques, rue Saint Guillaume (1937-38).

In Paris, he lived at 10, rue Philibert Delorme, in the 17th district, with his maternal aunt, Marcelle CREMIEUX.

During the war, 1939/40:

On 20/9/39 Francis enrolled at the Cavalry School of Saumur, where he remained until 20/1/40, then joined the 77th reconnaissance group. He went to war on a motorcycle and sidecar.

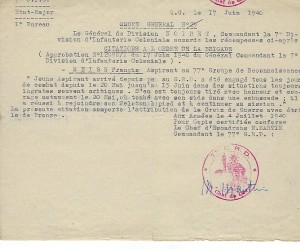

Text of the commendation that earned him the Croix de Guerre (French War Cross):

“Aspiring young man recently arrived at the 77th DSO. Was engaged in daily combat from May 20 to June 15 in situations that were always thankless and often critical. He always made it through with honor and courage, notably on May 20, when, having fallen with his sidecar during an ambush, he managed to re-join his platoon on foot and continue his mission”.

We do not know how or when he entered the Free Zone. A student card in his name, dated September 1940, attests to his enrolment at the Faculty of Law of Bordeaux, for the academic year 1940/41, to study for a doctorate in law, with an exemption from regular attendance in class.

In September 1941, he took refuge in l’Isle-Jourdain, in the Gers department, using a fake identity (“François Rousseau”). There he was employed as a manager for Louis Faure, a grocer on Avenue de la Gare, until 20 November 1943, when he had to leave l’Isle-Jourdain in a hurry to escape being enlisted in the Compulsory Work Service

During his time in l’Isle-Jourdain, he regularly visited his parents, who had left Bordeaux and taken refuge in Marseille. It was during one of these visits, on the beach at Bandol, in 1941, that he met the woman who would become his wife: our mother, Colette Roche.

The Resistance:

He joined the Organization of Armed Resistance (O.R.A.) in l’Isle-Jourdain.

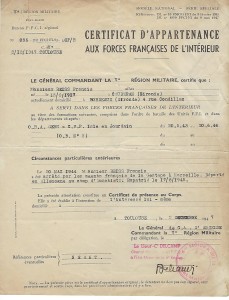

His or her FFI membership certificate (see attached photo) states:

“Served in the French Interior Forces as part of the following units: O.R.A Gers – C.F.P. l’Isle-Jourdain from 20/05/1943 to 20/06/1944.

On May 20, 1944, Mr. Francis Reiss was arrested by French Gestapo agents in Marseille. Deported to Germany to the Auschwitz camp. Repatriated on 17/8/1945.”

Another statement:

Captain Campistron, a veterinarian of the “Pommiès” irregular volunteer army corps, certifies that Francis Reiss, a resident of l’Isle-Jourdain, had in May 1943 signed a contract with Captain Mouly for the duration of the war in the said organization. From that date to the date on which he was called up to the Compulsory Work Service on December 20, 1943, he participated in the survey of the l’Isle-Jourdain area with a view to setting up an underground network and parachute landing sites.

Provided valuable assistance as an interpreter to American airmen rescued in the region or based in l’Isle-Jourdain in anticipation of their evacuation to Spain. Having resisted being drafted into the Compulsory Work Service, was arrested in Marseille on 20th June 1944, when he was trying to rejoin the “Pommies”.

When he fled the Gers, he was sheltered by his uncle André REISS, himself a refugee in Marseille, at 18 avenue Henri Fabre, and there he continued his activities in the Resistance.

It was also at this address that he was arrested by the Gestapo on June 20, 1944, along with all of the other the family members who were there that day. He was the only one who would be deported.

Initially interned at the Baumettes prison in Marseille, he was then transferred to Drancy on 24 July 1944.

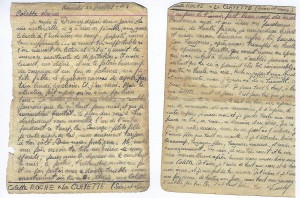

He managed to get a letter out to Colette:

The Deportation:

Auschwitz from August 4, 1944 to October 26, 1944 – number B 3897

Stutthof from October 27, 1944 to November 16, 1944

Echterdingen from November 20, 1944 to January 10, 1945

Vaihingen from January 10, 1945 to April 9, 1945

The following text in italics was written shortly after his return. He was planning to write a book:

“Introduction:

Arrest

Gestapo

Baumettes prison

Journey Marseille – Paris

Drancy The camp

The dread of leaving

The prognosis

The departure: 31 July 1944

Journey from Drancy to Auschwitz: 31 July – 4 August

Fellow travellers

Professor Voronoff

Struggling to breathe

Auschwitz, August 4 – October 26, 1944

“Arbeit macht frei”

The night of 4th August

This is not just a date: it is a symbol, of the nobility of the unprivileged noble and of how much freedom could be gained in the camp.

The night of arrival in Birkenau – selection – nakedness – prayers – roll call – trust – Wagner, Choudy and Dassas – waiting – showering – dressing – registration.

Block II – bullying – quarantine – 4 to a bed – the Bunkhouse II – the Oberkapo (the inmate in charge of the oversight team) Franz – advice from the old hands: fear of the Revier (infirmary) – “Nur Deutsch gesprochen” (“German only spoken”) – selections – “organization” – trade in cigarettes – exchange rates – gold trafficking – music – the brothel – the SS – the showers.

Sundays – the good kommandos (inmates forced to oversee the others) – the French, the Dutch, the Polish, the Russians, the Germans – the various categories of prisoners: politicians, Jews, gypsies, common-law, pederasts, critics of the Bible.

News from the outside (the Greek and the taking of Thessaloniki) – the Zulags (supplements, extra food) – the mentality of the veterans – the civil Meisters (foremen) – Cheisemeister (?) – Little Laüfer (errand-runners) and Dolmeister [interpreters] – experiments – “kein arbeit kein essen” (“no work, no food)- bombardment – honey of the SS.

The contrasts: gas chamber and crematorium chimneys – hygiene, cleanliness, disinfection, injections and the “krankenbaum” (infirmary).

The spectacles of those who were gassed- the kennel – the pigs’ swill – the roll calls – the punishments – the “sport” (exercise) – the hanged – the electric wires (the madman).

The 25 strokes, arms outstretched.

Memory exercises (La Fontaine)

The dead to be carried back – the Hungarian Jews on Friday evenings – the Sonderkommando (teams of inmates assigned to dispose of the corpses) – the selections – Wagner’s departure, his resignation.

The fog – lying down in the event of an incident – mützen ab! (everybody away!) mützen auf! (everybody up!) Ruhig Mensch! (At ease, fellow!) Appelplatz (roll-call grounds) – Schnell Schnell! (Go! Go!) – blows of a Gummi (rubber truncheon).

blows: giving or receiving them, no middle ground, neutrality impossible – breakdown of the hierarchy of age and civil status or intellectual values – one single value, the strength or protection of the sun.

The final selection: departure or gas chamber? – Sonderkommando rebellion – a lash from a civilian.

A piece of bread left behind in a bedroom.

Many complained and recriminated about fate in general or specific details of the camp’s life. For me, I felt that it was already a good enough achievement to be able to hold on, to be still alive and to be in physical circumstances that allowed the hope of being able to hold out.

An unrepentant optimist, I looked beneath myself and had to consider myself almost lucky. For these reasons I did not want change and tried to show others that, given the fact that we were convicts, our situation was not as bad as it seemed.

Maintaining a sense of humor, a sense of appreciation of the absurd and a sense of comedy.

Bound from head to toe by fate, I managed to remain a spectator and experienced a real and quite clear-sighted detachment, from which I even drew a certain solitary intoxication. Undoubtedly, because this analysis is retrospective, I was intoxicated to remain myself, intellectually, and to keep my faculties of reasoning intact in the grotesque and absurd madness that surrounded me.

I believe – and this I already knew clearly from the beginning of this experience – that I only avoided sinking by a very real duplicity. There were two of us within me: there was one who was suffering, who was hungry, who was worried about the anxiety he had to have for his people, who was recriminating and complaining, and then there was the other who looked at the first with interest, certainly, but with no more passion than a reader would feel for the hero of the book he was reading.

Since then, I have never completely abandoned this duality; within me there is almost always the one who acts seriously and the other, the spectator, always ready to smile on seeing the first one take himself so seriously.

Stutthof, October 27 – November 16, 1944

The journey from Auschwitz to Stutthof – arriving in the night – waiting on the platforms, boarding and bayonet blows.

Arrival at the camp – magnificent fir forests – the blocks – the administration and the Schreibers (inmate secretaries) – the waiting – the endless roll calls – the overcrowded camp, 4 per bed – no work – the soup – the French legionnaires – lack of water, of food, of clothing.

14 November, the death of the Swiss prisoner.

Long waits in the cold, squeezed together listening to Rabbi Cohn’s stories or dreaming up menus – snow – the work, bricks and cement – cabbage, carrots, kartoffelkommando (potato monitors) – 5 blows of a cane – dogs – SS woman – the hanging of the Schreiber [scribe/secretary] – the dead – discrimination by profession, pointless! – gradual weight loss – the departure.

Travelling: 4 days through snow-covered countries – the theft of tobacco and sausage from the SS – beatings with sticks – the discovery of the thief and the reaction of the SS – kicks on the head from iron-rimmed heels

Justification of the war or the camp: I quite like life, but being here I have accepted – accepted within myself, not only because it is an inevitable requirement – its loss, or at least the risk of losing it.

I play the game without cheating; I am beginning to know the rules and I endeavor to apply them. I know the risks it entails in both good and bad, and ultimately I believe that for me good prevails over evil.

“Man is an apprentice, pain is his master”

The camp has only one purpose. The justification of the camp is that it justifies me in my own eyes. Certainly I did not choose it and would not have done so had there been a free choice, but it is inconceivable to even imagine a choice. We just have to endure it. But can we not turn a situation we are forced to endure into a choice? It is in this sense that I “accepted” the camp and thus, to a certain extent, a part of myself no longer suffered.

If I were not afraid of being mistaken for a dilettante yet again, I would dare to argue with my comrades that being in the camp is liberating. One’s body is a slave but one is not just a body. And it is precisely this mechanical slavery of one’s body that frees one’s mind. For as little as we wanted this, we can have immeasurable freedom instead of constantly fighting with our soul and rebelling against the inevitable. There are always people who are a camp late.

Do not go to the opposite extreme and agree to play the opponent’s game. That would be cheating. We can still cheat by playing the game of who loses wins. And that’s no longer playing the game.

Playing the game: this is an expression I often use when talking to my comrades. But I seldom get the impression that I am being understood. I sometimes wonder if I am the one in the wrong and if I should grumble at the inevitable, complain all the time or talk about the past with regret and compare it to the present. But no, I’m the one who’s right. And without doubt I’m the one who’s the most realistic.

Do not assume that I am not nostalgic about the past, but I do not talk about it because I cannot draw any strength from it, or at least from nostalgia. And because my past, here, is still the only thing I cannot share, I save it for the lonely time before I fall asleep.

The camp, for me and others like me, and there must surely be some, is an opportunity. But if I said that, I’d probably be perceived as an aesthete. And I’m not an aesthete. I simply want to take advantage of this chance that I have been given. This camp, from which we will leave physically aged, for those who will leave it at all, is nevertheless a rejuvenating bath in which I want to immerse myself entirely. I feel fresh from this unique experience.

But I know that many of the good folk around me who are whining did not ask for any justification in their lives; many had probably already had their chance of happiness or fulfilled their duty, and that is something that should not be so very different.

Certainly, it was not me who wanted to come here, and I didn’t do much to deserve it. But the fact is, I am here. So I’m trying to make the most of it. It is in this sense that I play the game, that I seize the opportunity.

Secrets. I don’t think I’ve ever disclosed any serious ones of mine, of the type that matter to the person who discloses them. But I heard a lot of them, from a few comrades I liked a lot, and others too… But I don’t think they made any impression on me. I listened to them in silence, with interest, and I have not forgotten all of them even today. But only rarely did this move me. On the other hand, the butcher boy from Verdun, who spoke to me with tears in his eyes of the wine stews and game casseroles that he used to eat on Sundays at his boss’s house, that boy, I think, managed to move me. I mean him, of course, not the memory of the stew.

How many of us were able to appreciate the exceptionality of the situation?

Echterdingen November 20, 1944 – January 10, 1945

Arrival in the village of Echterdingen – the trek escorted by Luftwaffe soldiers – no SS: hope?

The aviation camp – our hangar: the two Feldwebel (staff sergeant): the SS and the aviator – the SS officer’s speech.

Everything is lacking – rapid organization of the camp – one blanket per man and only one man per bed – as time goes by the number of blankets increases and the number of men decreases.

The little train that goes by in the cold – the work not too hard – fake news – the cold becoming more and more intense.

Frostbite – the sick – the dead.

I stay at the camp – I am sick.

The death of Choudy (editor’s note: Khoudy) (noted on 22 December 1944 by Francis Reiss in his notebook).

Shoes for workers only.

Nonetheless, my optimism remains

Salomon’s bread.

Death of some of the French – my isolation increases.

Lack of water – hope and disappointment of a Christmas night – the reality of a slow death.

SS speech: if people die, it’s their own fault.

New speech: announcement of departure for a wonderful camp, a real sanatorium, where we would be well cared for, well fed, even overfed, without having to work.

Getting dressed into the oldest clothes – removing shoes (“you won’t need them anymore…”)

Departure of a batch of 50.

The next day, a second batch – I am one of them – resignation – a sudden turn of events: good soup, double ration of bread.

Getting on the lorry – crowding into the sinister truck.

The journey – the last one? – a stop in the woods.

The truck sets off again.

Particularities of the Echterdingen camp

and similarities with others.

The progressive stupefaction and degradation of man.

For a long time, I felt useless. There was a war, I was 20, it was a game. I had no responsibility in civilian life at the time, nothing other than the love for my parents and the friendship of my friends. I was a lightweight. How could war not have been a game for me? (I should come back to this – try to draw a parallel between war and the camp in order to show above all the differences, the absence of a reference point, a standard).

The camp is something else. It is a commitment of one’s entire being in spite of oneself. I arrived at the camp with responsibilities other than those that the 4 or 5 years of war had brought me. I was no longer alone. And suddenly I felt that this experience could have a positive impact on me and what regeneration (rejuvenation) I could find there, at least in a moral sense.

So it was of less importance whether I got out or stayed there. I was there, and that was the painful essence. I was suffering, but the fact that my suffering was offered to me rather than endured, made it seem to be mutual and less unbearable. I was beginning to understand what suffering could bring to those who understand how to accept it.

Of course, all this did not happen all at once, or as clearly as I am trying to transcribe it, but enough nevertheless that with just one of my comrades, a Jesuit father, I could discuss it at length. I was open to it before, without knowing why, and all of a sudden I was offered this wonderful option. Wasn’t I right to say that this was a unique opportunity? But who could understand me?

I am a mass deportee, someone about whom we sometimes talk but who is only rarely allowed to speak. In the camps, I never met “the gentry” no cardinals, no generals, no politicians, no well-known names other than homonyms or pseudonyms.

Was I not Rousseau?

The only one I got to know well during the four long days and endless nights of travel from France to Poland was Voronoff, a likeable old man, but he was not “the real one”, he was just his brother. Again, he was eliminated upon arrival, during the sorting, the “selection”. This word obliges me to digress immediately about the specialized language of the camps, those Towers of Babel.

The camps have their own language: a generic language (known to be) spoken in all of the camps because there have been transferrals. Each camp also has its own provincialisms, its own dialect. German is of course the official language – i. e. all commands, orders and registrations are in German – but it is also mandatory: “Nur Deutsch gesprochen”. But aside from the finer cruelty that involves separating detainees from their compatriots of the same nationality – is this even possible? – in practice everyone continues to speak his or her own language, with the exception of a common word pool, which is the language of the camp. I will not provide a lexicon, but there are some words, even if not translated, (which would hardly be possible because in life outside the barbed wire there is not the same need for such words), for which I shall at least try to give an outline. “Selection” is just one of many. Here is the rough list of a few of them without any attempt at explanation:

Selection – Canada – Appelplatz – Zulag – Dalmecher – Arbeit – Kommandofürher SS – Gummi – Brot – Organisation – Musik – Prominent – Meister – Chrismeister – Essen – Transport – Musulman – Wasser – Block – Stube – Revier – Laüfer – Schnell – Krankenbaum _ Kapo – Oberkapo – Sport – Mensch – Krematorium – Sonderkommando – Ruhig – Schreiben

Previously, I was useless and then the camp came along, because it was that which came to me, like redemption, a restoration… a blessing. I suddenly had, for no reason, the impression of participating in something very big, unique. But I still didn’t see how this could be useful. Slowly the idea emerged of redemption through accepted suffering, of the personal benefit that the camp could have. And later, I even saw how I could contribute here, to be useful not to my comrades, but ultimately to something greater in which I was participating, to humanity.

I now know that all this may be grandiloquent and ridiculous, but I cannot remain silent about the fact that I felt I was, through my suffering, which I was not aware of having deserved, participating in this communion of saints that the Credo describes. I finally understood the meaning of that expression, which had been so obscure to me. I finally felt that my life, because I was “suffering” it, could have a value. I felt that I too had a chance of being saved.

Doesn’t the very idea of penance, an act of redemption, find justification therein? All this became clear to me. The camp acted as a catalyst.

Vaihingen, January 10 – April 9, 1945

My conversations with the Priest at la Perraudière.

Liberation and the return journey:

The camp at Vaihingen (a commando camp, a satellite of Natzweiler-Struthof) was liberated by the French on April 9, ’45.

A photo shows him supported by a French soldier (Commander Saget).

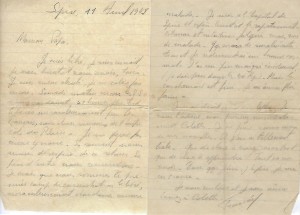

At the time of his release, Francis wrote to his parents but did not dare to tell them that he was very ill so as not to panic them.

A friend of the family recognized him in the hospital in Speyer and alerted Jérôme, his father, that he was in hospital but in too poor a state to be repatriated, and thought to be lost.

On May 15, he was still stuck in hospital, in bad shape and unable to move.

Jérôme, his father, came to pick him up, posing as an American officer on a special mission, wearing civilian clothes. He ate at the officers’ mess and managed to get a military ambulance to repatriate Francis to Strasbourg hospital. A telegram from Francis’ father to Colette:

That’s when our mother, Colette, was finally able to see him again. She later told us what struck her the most: “It was him, but his gaze had completely changed… But apart from that he was always making jokes.”

At the hospital he was given penicillin, which greatly improved the condition of his terrible scabies.

Then he was repatriated to Paris, but he no longer had any penicillin and the scabies infection started to spread again.

In Paris, he lived with his aunt Marcelle CREMIEUX, whose husband, Claude CREMIEUX, arrested by the Militia in Marseille on 25 January 1943 and deported to Sobibor in convoy 53, never made it back.

Our parents married in La Ciotat on September 8, 1945.

They settled in Bordeaux where Francis was the manager at Cresca, and they had five children: Marie-Christine (1946), Laurence (1948), Isabelle (1953), Marie-Hélène (1954) and Pierre-Jérôme (1959).

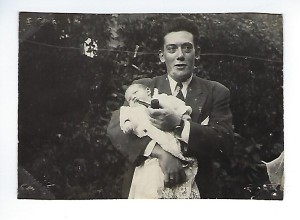

Francis and Marie-Christine, September 6, 1946

However, from 1952 onwards Francis’ health deteriorated due to the after-effects of his deportation.

In March 1957 he underwent a major neurological operation, which weakened him significantly.

It did not prevent him from maintaining his sense of humor and good character.

He died on March 8, 1965 in Bordeaux.

Biography prepared and written by Francis’ five children.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

[…] la biographie de Francis Reiss parue sur le […]

Merci chers cousins de ce témoignage.

Maman (Marise Crémieux) me parlait souvent de son cousin, témoin vivant de l’enfer nazi, soutenu par sa foi et les siens.

Bien à vous

Jean-François Hurstel

Toulouse

Bonjour cher cousin

C’est avec beaucoup de retard que je prends connaissance de votre mail.

Ca me touche beaucoup, et ça me ferait plaisir de vous rencontrer.

Toute la famille a lu le journal d’une adolescente juive sous l’occupation avec beaucoup d’émotion et de plaisir.

Je n’ose pas laisser mon adresse mail accessible, mais je vais essayer de vous joindre.

A bientôt j’espère

Marie Hélène Reiss

Bonjour Marie-Helene

Je suis à Toulouse et inscrit sur Facebook donc joignable par messenger et aussi ma page LinkedIn

Nous ne nous sommes pas vus depuis un mariage à Caussade vers 1972, et tu pouvais encore nous parler 😉

À bientôt

JF H

Je finis tout juste la lecture complète (autant que faire de peut avec certains passages des lettres manuscrites difficiles à déchiffrer) et suis profondément ému par la restitution si poignante que vous avez réussi à composer à partir des principaux événements et écrits de votre père.

Ma grand mère paternelle s’appelait Mathilda Brady, fille du co-fondateur de Cresca avec vos aïeux Reiss.

Mon père Bernard (1921 – 2011) a souvent évoqué comment nos familles ont déterminé laquelle des deux irait à Bordeaux pour se charger de la recherche et l’achat des produits, laissant l’autre à NYC pour se charger de la distribution… à la courte-paille apparemment ! À quoi tient le destin ?

Je suis né à Paris le 25 février 1965, qq mois je réalise avant le décès de votre père. Mon père a épousé une Française et ils ont décidé de s’établir en France.

Je réside à présent à Los Angeles, mais serai en France du 6 juin au 9 août pour tenir compagnie à ma mère qui fêtera ses 91 ans à Boulogne S/Seine.

Je pensais justement poursuivre les recherches que j’avais entamées sur les Reiss de Bordeaux et une simple recherche Google vient de me livrer ce témoignage que je vous félicite et vous remercie du fond du cœur d’avoir partagé.

Je serai ravi à l’idée de nous parler, qui sait nous voir, en France ou aux Etats-Unis, puisque nous formons, à travers nos familles, un trait d’union entre les deux pays.

Bien à vous

Philip

« Cresca : more than a little better! »

Cher monsieur,

je viens de transmettre votre message à Mme Reiss, qui n’a dit qu’elle ne manquera pas de vous contacter. Je vous remercie, au nom de l’Association Convoi 77, pour le témoignage que vous apportez sur les possibilités que celle-ci procure à des gens dont le destin a été si lié, de (re)nouer des liens.

Belle devise que celle de CRESCA.

Serge JACUBERT, membre du CA, responsable des relations enseignant, fils et neveu de déporté du convoi.

Je suis en effet rentré en contact avec Madame Reiss et espérons nous rencontrer. Toutes mes félicitations pour cet extraordinaire projet. J’en ferai part à différents amis professeurs qui pourront peut-être y faire participer certains élèves.

Bien à vous,

Philip Sinsheimer

J’ai lu avec intérêt cette biographie, rédigée par les enfants du déporté, Francis Reiss. Il a dû se sentir très aimé par ses enfants et sa femme. C’est une très belle histoire pleine d’optimisme malgré tout …

Anna Klinger