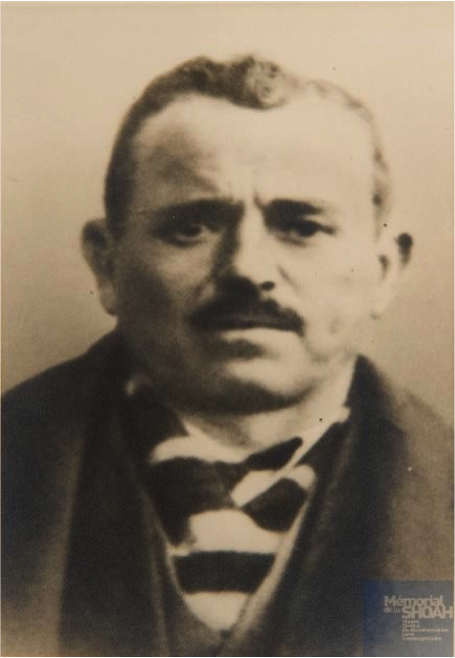

Gabriel ALFANDARI (1888-1944)

Birth: 1888 – Smyrna – Ottoman Empire

Death: October 31, 1944 – Auschwitz-Birkenau – Poland

Arrest: July 8, 1944 – Marseille – France

Photo: Gabriel Alfandari © Shoah Memorial, Paris / Isaac Alfandari collection

Gabriel Alfandari was born in Smyrna in the Ottoman Empire (now Izmir in Turkey) in 1888 (exact date unknown). His family were descended from the Jews who were expelled from Spain in the 15th century, and still spoke Judeo-Spanish, also known as Ladino.

His parents were David Alfandari and Refka (Rebecca in French) Nahmias.

According to his son Isaac, whom we met, Gabriel was happy growing up in Smyrna. He stayed there until the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish war in 1919, when he was 31 years old[1].

According to Isaac, his eldest son, Gabriel worked for a time as a salaried employee in an explosives factory in France. He also went to seek his fortune in Argentina, as did Vida’s father, Mr. Nahmiaz, after which he returned to Smyrna as a “protected French citizen”. This no doubt explains why he married relatively late in life.

In 1921, Gabriel married Vida Nahmias, or Nahmiaz, who was born on March 21, 1905. His osn said they both came from poor backgrounds and the only education they had was “religious Hebrew”.

The couple’s first three children were born in Smyrna: David in 1922, Isaac on February 15, 1924, and Rebecca in 1928.

In 1924, Gabriel and his brothers, Isaac, who was born in 1893 and Moïse, born on April 10, 1899, all moved to France in search of work. Gabriel still managed to travel back and forth between France and Turkey to visit his family.

A hardworking, well-integrated family

In September 1930, Gabriel’s wife and children also moved to France. They shared a house with another family in l’Estaque-Gare, on the outskirts of Marseille, in the Bouches-de-Rhône department of France. This was a poor, working-class neighborhood: their house at 266 rue Lepelletier had no running water, and the stove was the only source of heating. Gabriel ran his own store on rue Lepelletier, “next to the Bar des Amis”.

When they arrived in France, the children, like their mother, only spoke Judeo-Spanish.

The family grew larger on June 8, 1931, when baby Judith was born[2].

Gabriel and his family became French citizens on December 4, 1933[3].

According to what Isaac Alfandari told us when we met, Gabriel was a discreet, reserved man, a faithful husband, and very religious. He would go into the center of Marseille to buy kosher food and always closed his store on religious holidays.

Gabriel was a man who loved his family dearly. He was hardworking and concerned about his children’s future, and Isaac described him as a “workaholic”. In fact, Isaac told us that “besides running the store, this little man, who was only 5’1”, would peddle his wares on the markets and door-to-door: with a huge bundle on his shoulder and a heavy case in his hand, he would walk two miles to the Riaux neighborhood to sell on credit, with no collateral other than mutual trust and a written note in Hebrew in his account book.” During the school holidays, his son Isaac would sometimes go with him. “He never complained, was never ill, and was very proud to introduce his customers to his son, who was going to become a doctor”[4].

Gabriel’s wife, on the other hand, hardly ever left the house. He was the one “who did all the shopping.” She had plenty to do at home, with four children to care for. Nevertheless, when her husband was away, she served the customers in the store.

It was a hard life, and the only entertainment was going to the movies “in the surrounding area” on Sundays. In the summer, they would sometimes head to the beach with a picnic.

According to Isaac, everyone in their working-class community, even the police, referred to them as “the Jews,” but “there were no racist connotations”.

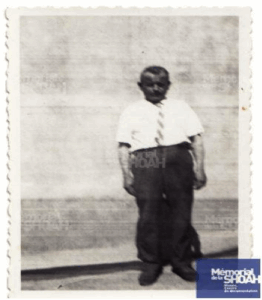

Gabriel Alfandari © Shoah Memorial, Paris / Isaac Alfandari collection

The war and ever-worsening living conditions

In 1939, the Second World War broke out. France surrendered in June 1940 and the armistice was signed on June 22. Under the terms of the armistice agreement, France was divided into zones and the Vichy government made the police and civil service available to the occupying forces. The German army invaded the southern part of the country, known as the “free” or unoccupied zone, on November 11, 1942.

The Alfandari family, who lived in the free zone, had to comply with the Vichy legislation, but life was easier than it was for the Jews in Paris and the rest of the occupied zone.

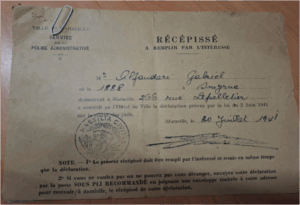

At first, the Alfandari family’s everyday life was largely unaffected. Gabriel continued to work as a street vendor, selling on credit to working class people, and was able to move around unhindered until June 2, 1941, when the 2nd decree on the Status of the Jews required them to take part in a census.

On July 30, 1941, the Alfandari family went to register themselves as Jews.

Photograph of the receipt for Gabriel Alfandari’s declaration that he was Jewish, now kept by his son Isaac Alfandari, who showed it to us when we met on March 11, 2025, at the Hauts de l’Arc secondary school in Trets

In 1942, Gabriel’s eldest son, David, was summoned to Hyères, in the Var department of France, to work as a tailor in one of Marshal Pétain’s youth work camps. He was able to keep a low profile there, but was expelled a month later because he was Jewish. Isaac continued to attend Saint Charles High School until 1942. In July that year, he passed his first baccalaureate exam. He was also “called up for civil defense.”

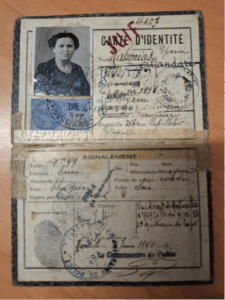

However, when the Nazis occupied the so-called “free” zone and the German army and the SS arrived in Marseille on November 12, 1942, living conditions slowly began to deteriorate for the Jewish population. The hunt for Jews was launched[5] and, as of December 11, 1942, the word “Juif” (Jew) was stamped on their identity cards.

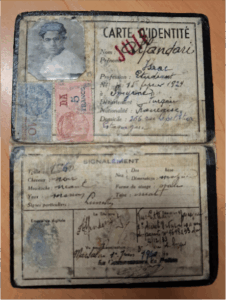

Photographs of Gabriel’s wife Vida’s and his son Isaac’s identity cards, stamped with the word JUIF (Jew), now kept by his son Isaac Alfandari, who showed it to us when we met on March 11, 2025, at the Hauts de l’Arc secondary school in Trets

After the roundup in the Old Port area of Marseille in January 1943[6], Gabriel’s children began using French-sounding first names, as advised by their friends. Isaac was known as Albert and David became Roger. Jews in the free zone had never had to wear the yellow star and this was not required even after the Germans arrived.

Gabriel’s eldest son, David, had been called up to work in a shipyard in La Ciotat as part of a compulsory work scheme called the STO. On May 10, 1943, as he was on his way to work, the Gestapo stopped him during a routine check. When David presented his identity card, which was stamped with the word “Jew,” they arrested him on the spot.

He was first taken to the Saint-Pierre prison, at 80 rue Brochier, in the 5th district of Marseille and then transferred to Drancy internment camp, northeast of Paris[7].

From that point on, the rest of the Alfandari family lived in fear of being arrested. In July 1943, Gabriel and his brother Moïse and their families left L’Estaque in an attempt to relocate to Gréoux-les-Bains, in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence department, which was at that time controlled by the Italians, who did not enforce the anti-Semitic legislation. The two men risked traveling back and forth to Marseille to keep their stores open. However, in October 1943, when they needed new ration cards, they all had to move back to Marseille. In order to qualify for rations, they needed proof of address, and their only permanent address was in Marseille.

They placed the children in the care of a Christian organization, which kept them hidden in a summer camp in Plan-d’Aups in the Sainte-Baume mountains in the Var department of France. After that, they all returned home to Marseille, except for Judith, the youngest, who was placed with a family in Avignon, in the Vaucluse department.

On September 24, 1943, Gabriel Alfandari was stripped of his French nationality.

After a number of other family members were arrested, the Alfandari family felt the noose tightening around their necks[8].

Gabriel and his family then spent some time Saint-Michel l’Observatoire, in the Alpes-de-Haute Provence department, but soon moved back to Marseille again.

On April 29, 1944, while Gabriel was in town, the Gestapo raided the family home, searched it, and found their life savings in a suitcase. The officers accused them of smuggling and confiscated the suitcase full of money. Gabriel soon discovered that they were not in fact Gestapo officers at all, but two Frenchmen in disguise who often used this trick to steal from people in Marseille and elsewhere in France. On April 30, Gabriel, who still believed in his country’s legal system, went to the police to file a complaint.

Arrest and deportation

On July 8, 1944, Gabriel, his wife Vida, and his daughter Rebecca were arrested in their home. His son Isaac, who was working with the STO[9], and his daughter Judith both escaped arrest[10].

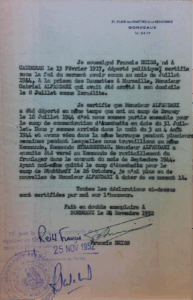

Gabriel was initially taken to the Gestapo headquarters at 425 Rue Paradis in Marseille, then interned in the Les Baumettes prison. He was transferred to Drancy in July 1944, but there is some uncertainty about the exact date. After the war, in November 1952, Holocaust survivor Francis Reiss testified under oath that he and Gabriel had followed the same route from Les Baumettes, via Drancy, to Auschwitz. He said that both he and Gabriel were interned on July 18. However, in September 1952, the French Ministry of Veterans and War Victims stated that he was interned on July 24, 1944.

Gabriel was deported on Convoy 77 from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 31, 1944. When the train arrived in the early hours of the morning, Gabriel was among the 291 men and 183 women who were selected to enter the camp to work. The other 832 people, including nearly 300 children under the age of 18, either died on the horrendous journey or were killed in the gas chambers. Their bodies were all burned in the crematoria near the women’s camp.

Francis Reiss’s testimony continued as follows:

“We arrived [in Auschwitz] during the night of August 3-4, 1944, and stayed in the same barracks for several weeks, during which time we worked in the same Kommando, the Kommando Strassenbau (road construction). Mr. Alfandari was then transferred to the supply Kommando Fraulager (women’s camps) in September 1944 […]. I heard nothing more about Mr. Alfandari after that”.

From the file on Gabriel Alfandari © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°21P417532_1232 (copyright 0455)

Gabriel is believed to have died on October 31, 1944.

Isaac told us that he probably died during the Death Marches, when the SS forced the surviving deportees to leave the camps in appalling conditions just as the Allies troops were advancing towards the camp. However, the Death Marches took place in January 1945. Gabriel most likely died earlier than that, either before or during a transport to Gross-Rosen, at the time when the Germans were sending able-bodied men and women from Auschwitz to other forced labor camps[11].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archives

– French Defense Historical Service in Caen, in Normandy

Gabriel Alfandari © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°21 P 417 532_1232 (copyright 0434 à 0480)

– Mémorial de la Shoah

Portrait de Gabriel Alfandari. Sans lieu ni date. – Mémorial de la Shoah

Gabriel Alfandari. Sans lieu ni date – Mémorial de la Shoah

Carte postale de Marseille, le quai du port et rue de la république – Mémorial de la Shoah

Vida Alfandari, posant de face en studio. Marseille (Bouches-du-Rhône), France, 1940. – Mémorial de la Shoah

La famille Alfandari. Sans lieu ni date. – Mémorial de la Shoah

Articles / Websites

– “Notre espoir est placé en vous: des survivants de la Shoah face à des lycéens” (“Our hope lies with you: Holocaust survivors meet high school students”) by O. Chaber, May 25, 2022 from the MadeInMarseille website

– “Le devoir de mémoire au collège Paul-Éluard”,(“The duty to remember at Paul-Éluard secondary school”) by Ms. Clavery, February 16, 2024, on the website of the Paul-Éluard secondary school in la Seyne-sur-Mer, in the Var department of France

– “L’attaque du train de la mort, un exploit méconnu de la Résistance ardéchoise dans la France occupée” (“The attack on the death train, a little-known feat of the Ardèche Resistance in occupied France”), by M-B Baudet, October 16, 2024, published on lemonde.fr

– “80 ans de la libération d’Auschwitz: rencontre avec Rebecca Marciano, rescapée du seul convoi de la mort détourné par la Résistance” (“80 years since the liberation of Auschwitz: meeting with Rebecca Marciano, survivor of the only death convoy hijacked by the Resistance”), by M. Buisson, G. Beaufils,

– Sarfati, C. Beaume, W. Gasiorkiewicz, H. Horoks for France Télévisions, published on January 27, 2025 on the FranceInfo website

– Geneanet

Testimonies

– Testimony collected and recorded during the visit on March 11, 2025, of Isaac Alfandari, son of Gabriel Alfandari, to Les Hauts de l’Arc secondary school in Trets, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of France. Rencontre avec le fils de Gabriel Alfandari au Collège Les Hauts de l’Arc à Trets

https://www.site.ac-aix-marseille.fr/clg-arc/spip/A-la-rencontre-d-Isaac-Alfandari.html

– Shoah Memorial website

Témoignage d’Isaac Alfandari, Juif de France (2021) – Shoah Memorial, Paris

Members of the History Club at the Hauts de l’Arc secondary school in Trets undertook historical research in order to write Gabriel Alfandari’s biography.

They drew on archived material and newspaper articles, and as a result, were able to meet Gabriel Alfandari’s son, Isaac.

Their project was then carried out in three stages: writing the biography based on the information they had gathered, recording the spoken version of the text, and then creating a “draw-my-life” video.

The students chose this format for its visual appeal and originality, and perhaps also because they felt it would be more easily accessible to middle school students.

They completed this project on a classroom whiteboard, using a phone without a tripod, and then using the Microsoft Clipchamp app.

Notes & references

[1] A conscription register in Grenoble for the year 1918 includes the names of Gabriel and Isaac Alfandari. They both lived at the same address, 135 cours Berrart (?) Bouchoyer Avold (??). Gabriel was listed as having been born on April 16, 1891, and Isaac on May 6, 1893, in Smyrna. Their parents were David and Rebecca. Both were laborers with a level 2 (average) education. They were exempted because they were “omitted from 1911” and “omitted from 1913” and were declared ‘fit’ for service “subject to a ministerial decision yet to be made.” There is no physical description of these men. Were they the same people? Were they French? They too were naturalized in 1933.

https://www.geneanet.org/registres/view/2091800/92?individu_filter=40994870

[2] Vida’s brother, Avram (Albert) Nahrmiaz, and his wife joined them in Marseille, as did Vida and Avram’s father, who was then 68 years old. They all lived very close to each other.

[3] Decree 9698 X 33. AN: 19770880/5

[4] Gabriel’s brother, Moïse, ran a small fabric store on Rue Lepelletier, the street on which Gabriel lived. He had two sons, André and Victor, and one daughter, Rébecca, born on July 10, 1933. He was naturalized by decree on December 31, 1929 (French Official Gazette dated January 12, 1930). His other brother, Isaac, was a “poor market trader.” He had one daughter, Judith, and four sons, Henry, Raymond, Victor, and Jacques.

[5] Checks became more frequent, “alerts followed one after another,” as did “STO searches” (on work sites for Jews). The “older” boys, David, Isaac, and their cousin André, were forced to go into hiding. In January 1943, Gabriel’s nephew Victor, a student at the electrical engineering school, “heard about the roadblocks and roundups being organized.” The family went to the police, who confirmed the plan. The children were immediately sent into hiding with the family of one of David’s friends, whom he had met during his brief stay at the youth work camp in Hyères. The Tassy family took them in, but there were Germans in the area. They therefore returned to L’Estaque, where, in the end, nothing had happened.

[6] From January 22 to February 17, the Germans undertook to “clean up” the old port district, which they referred to as “the wart of Europe” and a “pigsty.” For centuries, this working-class neighborhood had been home to a cosmopolitan population, including a significant number of Jews. Twenty thousand residents were evacuated from the old neighborhoods, which were then dynamited. Only a few buildings were spared. Behind this “public health” initiative lay a hunt for Jews and members of the Resistance. Not all Jews lived in this old neighborhood, and many of them had come from Paris or other cities in the northern zone. They were rounded up during “Operation Sultan” along with the Jews who lived near the Old Port. This huge police operation, led by the French authorities, resulted in the arrest of more than 6,000 people. They were first interned in Fréjus, and 1,642 people were deported, including 786 Jews who were all deported via Drancy. Faced with the scale and publicity of the roundup, the local population in Marseille responded by organizing a number of rescue operations. After these roundups, the Jews kept a low profile.

[7] On June 22, David sent a poignant message from Drancy camp to Mrs. Puget, the Alfandari family’s neighbor in Marseille: “I am just to let you know that I am well. I am leaving for a destination unknown, so please do not worry if you do not hear from me, as I will surely be unable to write to you. Do not worry about me. I hope that these difficult times will soon be followed by profound joy. There is no need to send any packages, as I will not be there to receive them. I will not be able to find out Albert’s high school exam results, but I have faith in him. I hope that the children and their mother have gone on vacation. I send you all my love and thank you for all the kind things I have always received in the parcels (please do not send any more parcels). Your son, who sends you his love and believes that we will be reunited very soon, God willing. Give my love to your uncles and aunts. David Alfandari.” The following day, the 23rd, David had no doubt heard more about where he was going. He sent another message, to his father this time, from the train: “They say we’re going to Metz, where we’ll be sorted, the men will go factories in Germany or Poland. I won’t then be able to send or receive any news.” He once again asked his family not to send any parcels and ended with: “Your son, who is thinking about his parents more than ever.” David was deported on Convoy 55. He was 21 years old.

[8] On December 30, 1943, Gabriel’s brother Moïse “was alone with his little girl in his store when two men asked him for his identity papers.” They then went to Gabriel’s and his brother Isaac’s homes to fetch the rest of the family, who were staying there. Moïse (born in 1899), his wife Djoya (born in 1907), and their son Victor (15 years old) were all taken away. Isaac says that their brother André “was held back by his friends in a bar.” They were transferred to Drancy on January 22, 1944. When he arrived there, Moïse had 58,400 francs taken from him during the search. They were deported on Convoy 67 on February 3, 1944, never to return. According to Isaac, “André and Betty were taken in by Mr. Thomas, a leading member of the Resistance, and André was wounded while firing at the Germans during the liberation of Marseille”. Moïse was said to have been “denounced by a local shopkeeper for being a Gaullist.”

[9] He worked at the Sotève factory, where the foremen, who knew he was Jewish, is protected and helped him.

[10] Isaac and his sister Judith sought refuge in the Sotève factory, where an engineer and his wife kept them hidden. They then took Judith to stay with their uncle Nahmiaz’s neighbor in Avignon.

[11] Rebecca and Vida, who were also interned at Les Baumettes, were deported on August 1, 1944, on a convoy that left directly from Marseille. They were very lucky: there were a large number of Resistance fighters on board that particular train. On the night of August 3-4, the same night that Gabriel arrived in Auschwitz), the convoy was diverted to Annonay, where the Vanox Secret Army resistance group attacked the train, released them and took them to safety in the Saint-Agrève hospital. Vida’s brother, Albert, managed to collect them from there and take them back to Avignon amid fierce fighting between the Resistance and the Germans. They were then reunited with Isaac and Judith. On August 25, Avignon was liberated without a fight. On August 28, after a seven-day battle, Marseille too was liberated.

Contrary to Gabriel’s wishes, his son Isaac did attempt to pursue his medical studies, but had to abandon them in order to provide for the family members who had not been deported. He took over his father’s business. In 2022, he handed over some family photos to the Shoah Memorial in Paris and recorded his testimony. He had already submitted a testimonial sheet to Yad Vashem, the Jewish Martyrs and Heroes Memorial Institute in Jerusalem, in 1996.

Français

Français Polski

Polski