Isic FISCHER

This biography was researched and written by a group of 11th grade students majoring in Organization of Freight Transportation at the Arcisse de Caumont high school in Bayeux, in the Calvados department of France, as part of their preparations for a field trip to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

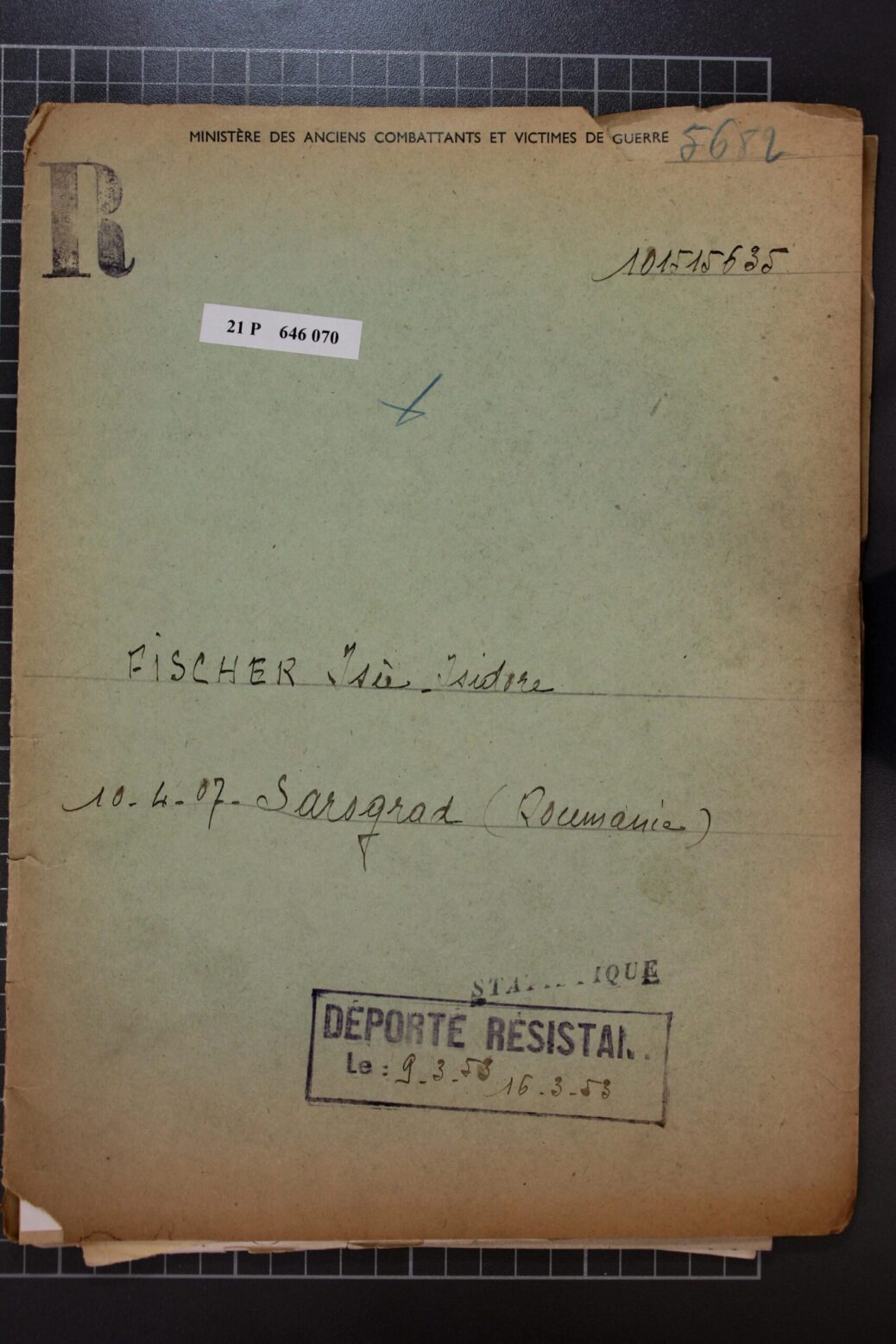

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, file on FISCHER_Isidore_21P646070

Isic’s life before the war

Isic Fischer was born on April 10, 1907 in Sarograd, in Romania. He moved to France in 1927, where he studied medicine at the University of Strasbourg until 1929, followed by the University of Lyon until 1933. On October 1, 1934, the Rhône prefecture officially declared him a Doctor of Medicine.

We have little information about Isic’s life leading up to the war, but in 1936 (and possibly earlier), he was living at 7, rue de l’Université in the 7th district of Lyon, in the Rhône department of France, together with his wife Clara, née Dermer, who was born on June 23, 1911 in Targu-Frumos, in Romania. He also worked as a physician at and had his doctor’s office at this address.

On September 3, 1935, Isic applied to be naturalized as a French citizen, but his request was put on hold. He reapplied on May 9, 1940, but again, to no avail. At that time, therefore, he was still a Romanian citizen.

1936 census listing for rue de l’Université in Lyon (Rhône department)

Source: Rhône departmental archives, online

Source: Rhône departmental archives, online

The outbreak of war

Isic volunteered to join the French army on March 2, 1940, and was assigned as an auxiliary physician to the Compagnie Muletière (Muleteer Company) 173-17.

The muleteer companies used pack animals, mainly mules, to transport equipment and supplies to the troops. In 1940, they were part of the Train Corps and were stationed mainly in mountainous areas, where they transported goods without which many operations could not have been carried out.

The 173-17 company was assembled between September 2 and September 9, 1939 in Venterol, near Montauban, in the Tarn-et-Garonne department of France, and was assigned to the 14th Army Corps.

It was initially based at Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur, in the Hautes-Alpes department, and then, from January through April 1940, at Nyons in the Drôme department.

It then moved on to the Maurienne valley to work with the 281st Infantry Regiment in Termignon, Lanslebourg and Bramans.

The company was disbanded on July 20, 1940 in Grenoble.

Source (in French): Ligne Maginot (the Maginot line)

As for Isic, he was demobilized on July 15, 1940.

Isic’s involvement in the Resistance

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, file FISCHER_Isidore_21P646070

There is a testimonial that states that Isic joined the Franc-Tireur movement in late 1941, although a certificate produced later only confirms that he was a member of the Resistance from January 1, 1943 to August 8, 1945

In fact, as of late 1941, Isic was responsible for propaganda and circulating an underground newspaper, as well as collecting funds to cover printing costs.

In 1942, when the STO (Service du Travail Obligatoire, or Compulsory Labor Service) was introduced, he began to produce bogus medical certificates and helped to make forged identity cards.

The Service du Travail Obligatoire or Compulsory Labor Service (STO): Founded by the Vichy government by a law passed on September 4, 1942, in order to meet demands for labor in Germany, the STO was in fact an expansion of the Vichy regime’s “Relève” (“Replacement”) program. This had begun in early 1942 and involved sending skilled workers to Germany in exchange for the return of prisoners of war (three workers for one prisoner). The “Relève” program was not a great success, however, and this prompted Laval to bring in a new law on February 16, 1943, which changed the way in which people were recruited into the STO: recruitment was no longer based on occupation, but on demographics. From then on, all young men born between 1920 and 1922 were called up. The STO was very unpopular and led to increasing hostility among the general public towards the collaboration policy. It also prompted some of the men who refused to take part in the STO to join the Resistance, particularly the “maquis” (local resistance groups). (Source: https://www.fondationresistance.org/)

On March 22, 1943, the Gestapo tracked down Isic, who only narrowly escaped arrest, so he and his family quickly went into hiding. They stayed first with a Mrs. Guirouvet and then with a Mr. Romeyer, in Lyon.

Although it was dangerous, he remained in contact with the resistance fighters from the Franc-Tireur movement, in particular to procure false identity cards.

The arrest

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. FISCHER_Isidore_21P646070

On Thursday, June 22, 1944, Isic went to a grocery store in Lyon to meet a man named Jankowsky (the grocer’s son-in-law), who handed him the new identity cards. Isic had previously provided Jankowsky with two identity photos, which were needed to make the cards. As Isic was leaving the grocery store to meet Kurt Haguenauer in a nearby café, four Gestapo men arrested him. Kurt Haguenauer was also arrested and deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

Isic was taken to Place Bellecour, to a building requisitioned by the Gestapo, and saw that they had a file with Jankowsky’s name on it, and also the two photos he had given to Jankowsky for the false identity cards.

Isic was tortured (he was dunked “in the bath” six times) but gave away no information about the Resistance.

After the war, on October 8, 1946, the Lyon Judicial Court sentenced Jankowsky to 20 years hard labor.

Memorial plaque on the corner of Place Bellecour and Rue Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in the 2nd district of Lyon. Source: The French Resistance museum online

The Consul of Romania’s intervention

The Romanian Consul’s testimony, dated November 30, 1945. Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Clara Dermer, Isic’s wife, notified the Consul General of Romania, Frédéric Bouvet, that her husband had been arrested. He then approached the head of the Gestapo to apply for clemency on Isic’s behalf. In fact, Isic was in breach of a Nazi law relating to the activities of foreigners, an offence punishable by death. As a result, the Gestapo relented and sent Isic to the Fort Montluc prison in Lyon.

Deportation

Having been detained in Fort Montluc in Lyon since June 22, 1944, Isic was transferred to Drancy transit camp on July 3. Designed in the 1930s to provide low-cost housing for local families, the unfinished buildings were initially used as an internment camp and then as a transit camp for Jews. In total, close to 63,000 Jews were deported from Drancy to Nazi concentration and extermination camps. Isic was deported from Drancy on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944 and arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944.

He was selected to enter the Auschwitz camp to work and was interned there from August 3 to October 26, 1944, when he was transferred to the Stutthof camp, near Dantzig (now Gdansk in Poland) where he was held from October 28, 1944 to May 9, 1945.

During this time, he spent time in the main Stutthof camp and two of its “satellite” camps:

- Stutthof from October 28 to November 22, 1944

- Burgrabben from November 22 au March 9, 1945

- Troyl Dantzig from March 9 to March, 1945

- Stutthof from March 24 to May 9, 1945

The Stutthof camp

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Stutthof was originally an internment camp for civilians, managed by the Chief of Police in Danzig. In November 1941, it became a “re-education through labor” camp, run by the German Security Police. In January 1942, Stutthof was classed as a concentration camp.

Tens of thousands of people, perhaps as many as 100,000, were deported to Stutthof.

Living conditions in the camp were exceptionally harsh. Many of the prisoners died during a typhus epidemic that swept through the camp in the winter of 1942, and again in 1944. Prisoners that the SS guards deemed too weak or too sick to work were exterminated in a small gas chamber within the camp. In June 1944, Zyklon B gas was used there for the first time. Doctors in the infirmary also killed sick and wounded prisoners by lethal injection. In total, more than 60,000 people died in the Stutthof camp.

Forced labor and sub-camps

The Germans used the prisoners in Stutthof to perform forced labor. Some were assigned to companies belonging to the SS, such as the nearby German Equipment Works (DAW), while others were sent to work in local brickworks, private industrial plants, the camp workshops and even to work on farms. In 1944, as the concentration camp prisoners’ labor became increasingly central to weapons production, Focke-Wulff built an aircraft factory in Stutthof.

Evacuations and death march from Stutthof

The Germans used the prisoners in Stutthof to perform forced labor. Some were assigned to companies belonging to the SS, such as the nearby German Equipment Works (DAW), while others were sent to work in local brickworks, private industrial plants, the camp workshops and even to work on farms. In 1944, as the concentration camp prisoners’ labor became increasingly central to weapons production, Focke-Wulff built an aircraft factory in Stutthof.

In late April 1945, the surviving prisoners were evacuated from Stutthof by boat, as the Russians had surrounded the camp on all sides. Once again, several hundred prisoners were herded into the water, but this time they were left to drown. More than 4,000 others were sent to Germany in small boats, some to the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg, others to camps along the Baltic coast. Many of them drowned on the way. Shortly before Germany surrendered, a number of prisoners were transferred to Malmö, leaving Sweden, which was a neutral country, to take care of them. An estimated 25,000 deportees died during the evacuation of Stutthof and its sub-camps. In other words, only half of the prisoners survived.

On May 9, 1945, when the Russian troops liberated Stutthof, about a hundred prisoners who had managed to hide during the final evacuation of the camp were still there. Isic is thought to have been among them.

After the war

After the Stutthof camp was liberated, Isic was repatriated to France. He arrived in Valenciennes, near the Belgian border, on August 8, 1945 and subsequently made his way back to Lyon.

On October 8, 1946, the Provisional Government of the French Republic issued a decree, which was published in the French Official Gazette, granting Isic and his wife Clara French citizenship.

On December 1, 1947, The Ministry for Veterans’ Affairs and War Victims issued Isic with a certificate confirming that he had been deported.

In 1949, Isic applied for a deported Resistance fighter’s card. After sending a number of reminders to the Ministry of War Veterans and Victims of War, he finally received the card, numbered 101515635, on March 7, 1953. This entitled him to a provisional invalidity pension as he was deemed to be 10% disabled: having contracted typhus while he was interned, he still had problems with his right leg. He was also awarded a silver epidemic-survivor’s medal.

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, file on FISCHER_Isidore_21P646070

Once he had settled back into life in Lyon, Isic began working as a physician again. He died on April 28, 1992, at the age of 85

Français

Français Polski

Polski