Jean DOMBLATT (1887-1957)

Photograph of Jean Domblatt

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-63-5-875-13

I. THE FIRST PART OF JEAN DOMBLATT’S LIFE

A. JOINA DOMBLATT’S YOUNGER YEARS IN POLAND

Joina, later know as Jean, Domblatt, was born on September 12, 1887 into a large family in the town of Szydlowiec, Poland. His father was Nata, a tailor, and his mother Zelda was a housekeeper. He had four brothers. He went on to marry Léa Domblatt, née Rozenswerg, with whom he had five children, four girls and a boy.

Joina married Léa in February 1906. They had their first daughter, Zlata (known as Sophie in France) in Poland in 1906, followed by Sola (Sarah) in 1908 followed by Faïga (Paulette) in 1912, both born in Poland..

B. EMIGRATION TO FRANCE AND LIFE BETWEEN THE WARS

Their last two children were born in France: Rose in 1915 in Paris and Max, in 1918 in Limoges, in the Haute Vienne department of France. This is how we found out that the Jean and his family moved to France between 1912 and 1915. His four brothers all emigrated to the United States, although we do not know why they chose to move there.

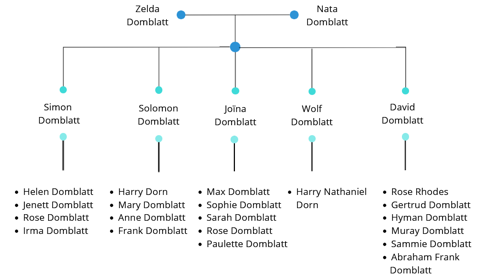

Family tree that we drew up using data from https://ancestry.com

We tried to figure out why Jean and his family left Poland for France in the 1910s. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, France was undergoing a period of rapid industrialization. The labor shortage in agriculture, construction and industry drew in migrants, in particular from Poland. They were also trying to escape economic and political instability in their home countries, and, in the case of the Jews, persecution and pogroms.

During the First World War, labor shortages in France prompted the government to appeal to foreign workers to help boost the agricultural, industrial and military sectors. This made it a particularly attractive destination, and as a result, many thousands of Polish people settled in France between 1890 and 1914.

Many of them were offered work the Limousin region, where they still continued to struggle financially and living conditions were poor. Jean and his wife Léa, however, probably chose to move to Limousin to get away from Paris. The last of their daughters, Rose, was born in Paris in 1915, and their son Max in Limoges in 1918, which means they left Paris during the First World War. Did they leave purely for work-related reasons? Was it to escape shortages in Paris? Or to distance themselves from the front lines in northern and eastern France? We found nothing to pinpoint the exact reasons why the Domblatt family decided to move to Limoges.

After the war, some migrants, Polish people in particular, decided to stay on in the Limousin region for good, thereby helping to rebuild the country. They played an important role in the war effort and made a lasting impact on Limousin’s demographics and economy. Others, such as the Domblatt family, moved back to Paris.

On December 3, 1926, the articles of association of the mutual aid organization Les Amis de Szydlowiec (Friends of Szydlowiec) were filed with the Paris police headquarters. It was based at 4, passage Sainte-Avoye, and Jean Domblatt was the treasurer. Such organizations bought plots of land in the Jewish section of the Bagneux cemetery in Paris, and the “friends” in question were often later buried there.

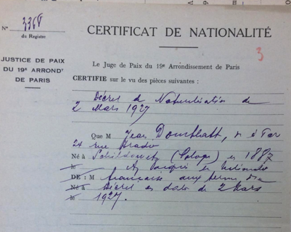

Jean, together with his wife Léa, were naturalized as French citizens on March 2, 1927.

Jean Domblatt’s certificate of French nationality

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-875-9

II. HIS LIFE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR

A. ARREST AND DEPORTATION

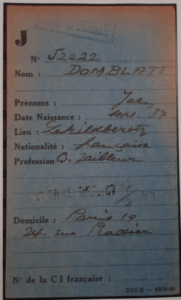

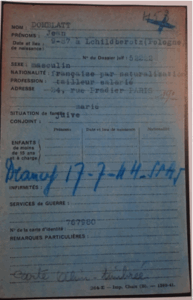

The only records we have of Jean before he was arrested are two identity forms, dated 1940 and 1941. The Vichy government passed a series of laws on the status of Jews, one of which required them to register with their local police station.

The declaration that Jean Domblatt made in the prefecture in 1940

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, prefecture files, adults © Shoah Memorial / French National archives, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5638_040577_L

The declaration that Jean Domblatt made in the prefecture in 1941

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, prefecture files, adults © Shoah Memorial / French National archives, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5609_005646_L

On November 21, 1939, Jean’s daughter Rose was still living at 24 rue Pradier: an experienced shorthand typist, she placed a job-hunting advertisement in the French newspaper L’Intransigeant. On February 8, 1940, she was still looking for work, even though, at the time Jews had not yet been banned from working in certain professions.

After that, we found no trace of Jean until July 15, 1944, when the militia, which was made up of civilians with links to the French police, arrested him in his apartment at 24 rue Pradier in the 19th district of Paris. The records state that he was arrested because he was an “Israélite”, meaning that he was Jewish.

His wife, Léa, was arrested at the same time. Two people, Henri Fleurier (a storekeeper) and Marie Hembise (the building’s concierge), witnessed the arrests and both testified that the militia carried out the arrest.

At 3:15 a.m. on July 16, father, Jean, Léa and their son Max, who had been arrested the previous day, all arrived at the Police Headquarters depot. The consignment list reads: “Affaires juives” (Jewish Affairs), which refers to the authorities who issued the order for Léa and Jean to be detained. Beside Max’s name, it reads: “Direction Permilleux”, which refers to Inspector Permilleux, who was in charge of the Jewish Affairs Department of the judicial police.

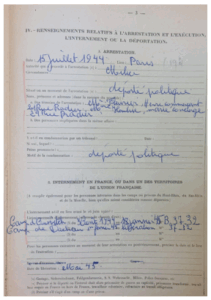

Report on Jean Domblatt’s arrest

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-875-4

The police report, dating from 1952, states that Jean was arrested “in retaliation, his son Max having been arrested the day before”. It is difficult for us to interpret this report without further details, and in the absence of another source to compare it with. (The report also contains an incorrect date, 1944 having been replaced by 1952).

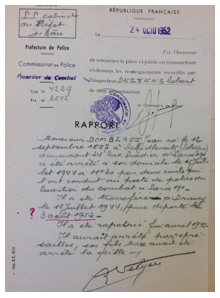

Information on Jean Domblatt’s arrest

Source: File on Jean Domblatt ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref.-21-P-635-875-11

Jean was transferred to Drancy on July 17, 1944, along with his wife Léa and their son Max. They were assigned the numbers 25,210, 25,211 and 25,212 respectively. The Drancy record cards provide information on where in the camp they were held. Jean and his son Max were initially housed in room 4 on staircase 18, and then moved to room 4 on staircase 3. The letter B, in blue, meant that the prisoners could be deported immediately. The letter L was added later (after the war) to denote that Jean was eventually liberated.

According to the Jean’s search receipt from Drancy camp, which is kept at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, he had 2,563 francs confiscated from him when he arrived there. This was not a huge sum, but in those difficult times it was not insignificant either. He must have taken his entire fortune with him when he was arrested.

Jean Domblatt’s internment record from Drancy camp

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, Drancy files, adults © Shoah Memorial / French National archives, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5688_125371_L

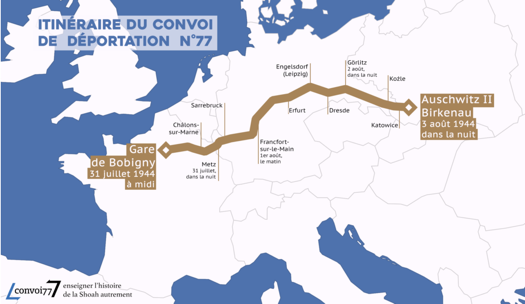

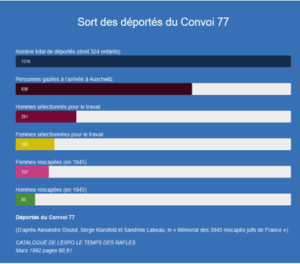

Jean remained in Drancy for 15 days before being deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 on Convoy 77, the last of the large convoys of Jews to leave Bobigny station for the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and killing center.

Aside from the exceptionally large number of people aboard, including children and babies, this convoy had all the hallmarks of having been organized in a hurry, just as the Allies were advancing rapidly towards Paris and the Germany army was on the verge of defeat. The deportees’ origins and nationalities varied widely (although more than half were French), and some of them (soldiers’ wives, spouses of Aryans, etc.) had already been interned for some time in the Drancy satellite camps, known as the “Parisian camps”. The Nazis had, until then, made them exempt from “transport”, i.e. deportation.

Convoy 77 left Drancy on July 31, 1944, just seventeen days before the camp was liberated. There were 1306 people aboard, including 324 children and babies, crammed into cattle cars. We know from the testimony of a one of the survivors, Hélène Ramet, that when the deportees left Drancy, they were given a little food and allowed to take their belongings with them. Then, in groups of sixty men, women and children, they were locked into cattle cars, as Jean himself also testified after the war. The four days and three nights they spent in the cattle cars were truly dreadful, as there was no room to lie down, and the one bucket that served as a toilet was only emptied once a day.

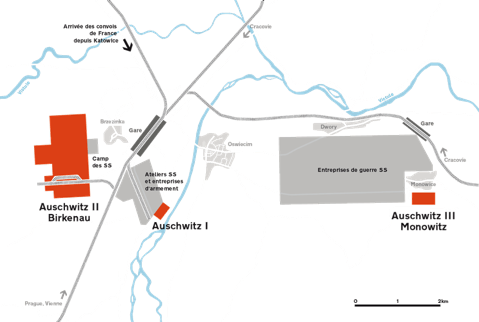

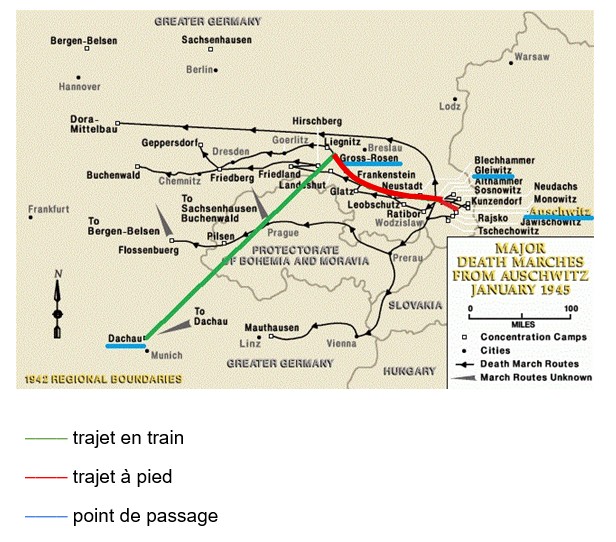

The route taken by Convoy 77

Source: Convoy 77 website

B. JEAN’S TIME IN AUSCHWITZ

The convoy arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau during the night of August 3 – 4, 1944, at around three in the morning.

Plan of the three sections of Auschwitz (the concentration camp, the killing center and the factories). ©LM Communiquer & associates, for the town of Bobigny

The convoy came to a halt in the Birkenau side of the camp. The Judenrampe had not been used since May 1944. Immediately after they arrived, with the SS yelling at them, the selection took place. The deportees selected for forced labor were sent into the barracks in Auschwitz, where they were stripped, shaved and showered, and then given some clothes. Almost two thirds of the people on the convoy, including Jean’s wife Léa, were sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered.

Along with his son Max, Jean made it through the selection process, which, given the he was 57 years old at the time, is astonishing. In addition, in her 2019 paper entitled “Une micro-histoire de la Shoah en France. La déportation des Juifs du convoi 77” (A micro-history of the Holocaust in France: The deportation of the Jews on Convoy 77), Anaëlle Riou notes that “there is nothing in his personal file to explain why any particular aspect of his trade [tailor] qualified him to work in the kommandos in Auschwitz.”

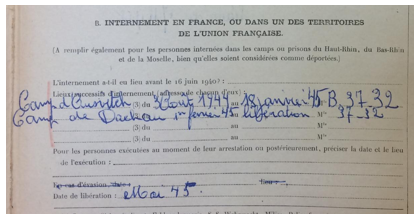

Jean, along with everyone else who passed the selection process, had a serial number, in his case B37-32, tattooed on his arm. We researched the meaning of the letter “B”. Originally, the letter “B” in front of an Auschwitz serial number was used to specify that the number had been assigned to a woman. This began in May 1944, with the mass arrival of Jews from Hungary, and was a special series of numbers established in response to the huge influx of deportees at the time. Normally, the tattoo was just a number, with no letter. The men who arrived from Hungary at the same time were assigned a number from another series, also without a letter. From that point on, the “B” series was used for women of all nationalities who were admitted to Auschwitz. There were, however, a few exceptional cases in which men’s serial numbers also began with a “B”, including the men who arrived on Convoy 77, such as Jean and his son Max, who was assigned the number B37-33.

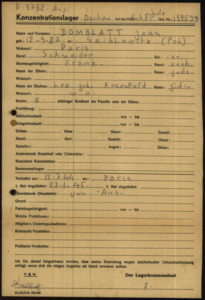

Jean’s detention record.

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-875-2

The Auschwitz-Birkenau camp was part of Nazi Germany’s “Final Solution”, a policy aimed at the mass extermination of all the Jews in Europe. Built in Nazi-occupied Poland, initially as a concentration camp for Poles and later for Soviet prisoners of war, the camp was soon used to hold prisoners of many other nationalities. Between 1942 and 1944, it became their main killing center, where Jews were tortured and executed on the basis of their so-called “race”. In addition to the mass extermination of over a million Jewish men, women and children, and tens of thousands of Polish victims, Auschwitz also served as a killing center for thousands of Roma and Sinti people as well as other prisoners of various European nationalities.

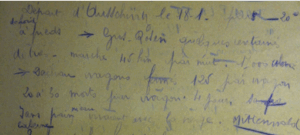

On June 5, 1945, after he returned to France, Jean was questioned about the deportation. The notes made at the time are short and some parts are illegible, but we managed to transcribe the following: “In Auschwitz, some people were selected for the ovens and others for work. Every week for 3 months, selection for the crematorium, then every fortnight for 3 months. Birkenau, 3 miles from Auschwitz, with 3 crematoria working day and night. 5 million Jews, women and children burned”. He went on to talk about the destruction of the crematoria: “At the beginning of October 1944, 2 furnaces were demolished; the 3rd was left to burn the dead.”

When they entered the camp, the deportees were sent to barracks, in which men and women were segregated. These barracks contained numerous rows of three-tiered bunks, originally designed for four people. Up to twelve people were crammed into these beds, with no mattresses or blankets, and according to one survivor, Hélène Fenster Ramet, “to turn over, all six bodies had to turn at the same time”. The living conditions in Auschwitz were appalling. There were only two toilets for the men, and it was the same for the women. This increased the spread of contagious diseases. There was a routine in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. The day began with a type of coffee, followed by a roll call, and then the prisoners went to work. There was then a second roll call and the evening meal, which consisted of a loaf of bread (called a Zulag) shared between five people, a slice of sausage, a knob of margarine or a spoonful of soft cheese, and some thin soup. After that, it was time for bed.

The poor sanitation and lack of privacy also contributed to the abuse suffered by the prisoners: the toilet block housed long rows of wooden benches with holes in them. What made matters worse was that there was no toilet paper, so the deportees sometimes cut a little square out of their shirts as a substitute.

During the first week or so, the newly-arrived deportees spoke with the existing prisoners to find out what life in the camp was like and what happened during the selections. All prisoners in Auschwitz had to undergo regular selections to check that they were still fit for work and that they were not trying to hide the fact that they were sick. They were examined closely, and any suspicious signs (redness, spots, paleness or thinness) could get them sent to the gas chambers and executed.

For Jean and Max, with no news of Lea, the first few days must have been terrible. Even if they didn’t realize right away what had happened to her, the other deportees would soon have explained what the constant smell and smoke from the chimneys at Birkenau were all about.

C. TRANSFERS AND LIBERATION

1) From Auschwitz to Dachau: the “Death Marches”

In late 1944, the Red Army began a major offensive aimed at defeating Nazi Germany as quickly as possible, the objective being to take Berlin. The German authorities urgently needed to decide on what to do with the prisoners in Auschwitz. Himmler’s delegate in Silesia, Heinrich Schmauser, received the order, probably in mid-January 1945, to evacuate any prisoners who were fit enough to be moved. This marked the beginning of the “Death Marches”, the evacuation of the few remaining deportees from the concentration camps and killing centers at the end of the Second World War.

The Nazis had three main reasons for the evacuating the camps:

- The SS leadership did not want the prisoners to fall into enemy hands alive and be able to tell their stories to the American and Soviet soldiers who liberated them.

- They felt they needed the prisoners to maintain arms production wherever possible.

- Some SS commanders, including Himmler, held the irrational belief that Jewish concentration camp prisoners could be used as bargaining chips to negotiate a separate peace in the West, which would have ensured the survival of the Nazi regime. The SS soldiers therefore burned the camp records and filled in the pits containing their victims’ ashes with earth. However, they did not manage to erase all the incriminating evidence before they fled.

On January 18, 1945, Jean and his son Max were evacuated from Auschwitz along with all the other prisoners who were fit enough to walk. Whether they were able to see each other, talk to each other or share a hug, we do not know. Historians estimate that between January 17 and 20, 58,000 people were evacuated. Jean was transferred in several stages: from January 18, 1945 to January 28, 1945, he walked from Auschwitz to Gleiwitz and from there to Gross-Rosen. In his testimony, Jean states that they walked “45 km [28 miles] a night, at -20°C [-4 F]”. Then, from January 28 to February 1, he was transferred from Gross-Rosen to Dachau by train. Jean later said that they traveled “in boxcars, 120 of them. 20 to 30 died in each car. 4 days. No bread or water. Lived on snow”.

Jean Domblatt’s testimony, dated June 5, 1945

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, AN F9 5584

The route that Jean Domblatt is thought to have taken during the Death Marches (train route in green, walking route in red, stopping places in blue)

Source https://ushmm.org

These marches took place in appalling conditions. The deportees walked for miles in freezing temperatures, hungry and thirsty. Those who could not go on were immediately shot by the SS, so as not to leave any witnesses alive. When they were transferred by train, they were loaded into cattle cars or some sort of open flatbed wagon, where space was so tight, they had to fight for it. Some people fell off and were executed by the SS soldiers who were in charge of the convoy. Thousands of prisoners died of hypothermia, starvation and exhaustion.

We were able to obtain the testimony of survivor Henri Graf, who was evacuated from Auschwitz on the same day as Jean Domblatt:

“January seventeenth or eighteenth … we heard: ‘You’re not going to work today. We’re evacuating you. We’re evacuating the camp’. So they set up tables in front of the main gate. There were lots of cans of food, lots of bread… I took two loaves of bread and two cans. I had a satchel. I don’t even remember where I found it … It was January ’45, -25 [-13F], a thin shirt on my back, a jacket that like straw, unspeakable clogs on my feet, and we set off walking. [This was] the beginning of what later became known as the “death march” … We walked sixty kilometers [37 miles] through the snow … We walked for three days. Three days and two nights … [Then began] the thirst. Thirst caused … by the cold, dry climate. Because, over there, the cold cracks like a whip. Not a damp cold [but] a dry cold you could cut with a knife … it dries out everything … That satchel, those two kilos of bread and those tins of food weighed me down. I had to keep switching shoulders… and I did the same as everyone else: I threw everything away. I had nothing to eat. I wasn’t hungry as I was so thirsty … We picked up the snow on the ground, which was dirty … There were two or three thousand people ahead of us who had trampled on it. We picked up the snow and sucked it … At the time, it was icy and felt good. Thirty seconds later, it burned even more … And we had diarrhea … We kept soiling ourselves. We were soaked in shit … At one point, as I was walking along, I saw a huge frosty fountain spouting water everywhere: I was hallucinating because I was thirsty. There was no fountain. There was nothing at all… Behind us, we could hear the gunfire. Anyone who couldn’t keep up or fell down was killed by the SS… And then we arrived at a little station called Gleiwitz. There they made us get into open freight cars. They had been used to transport coal. The floor of the cars was covered in coal dust. It had snowed on top of that … so, with the heat of the bodies, as the melting snow mixed with the coal dust, I can’t begin to tell you the state we were in. And then we arrived at Gross-Rosen.”

Henri Graf, testimony given on October 5, 2005 for the UDA (Union des Déportés d’Auschwitz, or Auschwitz Deportees’ Union)

Jean arrived in Dachau on February 1, 1945, probably at the same time as his son Max. The records show a new serial number, 139,599. He was assigned to the kitchen and worked as a potato peeler, as was his son Max. Did they continue to work side by side? We have no records to confirm this, so we can only speculate. However, this was an indoor job, under cover, and meant that the prisoners assigned to this task were sometimes able to steal a little extra food, which increased their chances of survival.

This was vitally important, as living conditions in Dachau were deteriorating by the day as the Allies approached, as Charles Joyon, Max’s fellow prisoner in the barracks in Dachau, explained in his book Qu’as-tu fait de ta jeunesse? (What did you do when you were young?). He described Max as a young man whose mental health was severely affected by the deportation.

“Around midday, sometimes at eleven in the morning, more often at two or three in the afternoon, we were given our meagre ration, a ladleful of foul, clear broth which, as the Boche defeat was looming, became ever more foul and even thinner […].

In late January, a large number of Auschwitz deportees, all Jews, were evacuated to Dachau. The countless deaths that had left huge gaps in the camp’s workforce were soon filled. My bunkmate was a young Jewish man from Marseilles by the name of Attali Israël. He was barely 16 […]. My other bunkmate, Jean-Pierre Lhemann, who was from originally from Alsace, had been living in Paris and was arrested in Normandy […] An artist, José Ortéga, from Argentina, slept underneath us […] Beside him there was a young Jew with neurasthenia, Max Domblatt, who wept and moaned non-stop. Then there was Paul Messey, an 18-year-old from the Vosges region, who clung to life for several months and finally succumbed the day after the camp was liberated […].

I spent several weeks in that room 4 in block 17. That took us into April. The camp was abuzz with the most contradictory rumors about the Allies’ advance and the fall of the main German cities.

Around April 20, after several weeks of uninterrupted bombing raids across the region and in particular on Munich, the first of the evacuees from the Buchenwald camp arrived in Dachau. The arrival of this group of living dead was an atrocious sight. […] Of the 200,000 men who had been in the camp, only around 25,000 were still alive”.

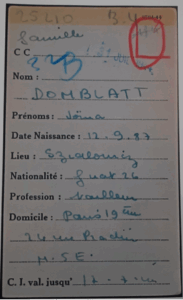

Joina Domblatt’s record from Dachau camp – DACHAU envelope – digital archives -1.1.6.2 10024075

ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives

2) From Dachau to Mittenwald

According to several testimonies, including Jean’s own, towards the end of April 1945, the Nazis transferred Jews from the Dachau concentration camp by train or on foot to Mittenwald in the Isar valley in the Tyrol.

The Mittenwald concentration camp was in the village of the same name in the Bavarian Alps in Germany. The camp was one of a less well-known system of camps used by the Nazis. The prisoners there were mainly used for construction work, in particular on military infrastructure and armaments production. Prisoners in Mittenwald were subjected to extremely harsh working conditions and heavy surveillance by brutal Nazi guards.

In April 1945, as the end of the war drew near, the Allies, in particular the Americans, were advancing into Germany. The American army liberated the Mittenwald camp on April 29, 1945. By that point, the Nazis were already retreating and many concentration camps had been evacuated. The prisoners were forced to march to other camps or further into the Reich. As Jean explained after he returned to France, he “stayed with the Americans”.

To shed more light on this part of Jean’s journey, we focused on the testimony of a Maurice Cling, a Frenchman. He and two other eye witnesses told some students about how they had suffered under the Nazi regime in the run-up to the inauguration of the memorial. These were Maurice Cling’s earliest memories of Mittenwald and the death march along the Isar Valley in April 1945. Maurice Cling, who was born in 1929 and died in 2020, lived to bear witness to the atrocities of the Holocaust. He was evacuated to the Dachau camp in January 1945. In late April 1945, the Nazis transferred him and around 1,700 other Jews by train from the Dachau concentration camp, where he had been since January 1945, to the Tyrol. He was eventually liberated by an American unit on April 29, 1945 at Mittenwald, on the border between Upper Bavaria and the Austrian Tyrol, just as the German guards were fleeing.

After they were liberated, the Allies and various aid organizations took care of the survivors and did their best to provide medical care to help them recover from the horrors they had experienced. Jean was repatriated to France by train on May 31, 1945 via Mulhouse, near the German border, and arrived in Paris on June 2, 1945.

III. HIS LIFE AFTER THE WAR

After he was liberated in 1945, all we know about Jean is that he lived until 1957. Unfortunately, we have very little information about his life after the war.

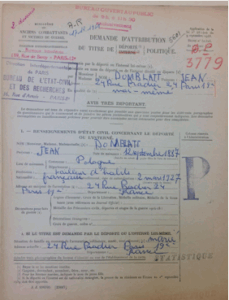

We do know, however, that he applied for the status of “political deportee” on December 5, 1951. He was notified that his application had been successful on November 27, 1953. As a result, he received a payment of 13,200 francs on December 29, 1954. Political deportees were entitled to financial compensation, medical benefits, specialized care and, in some cases, a pension if they had suffered serious long-term physical or psychological damage.

Jean Domblatt’s application for political deportee status

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref.-21-P-635-875-2

We also know that after he returned to France, he went back to live at 24 rue Pradier in the 19th district of Paris, as did his son Max.

Phot of Jean and [we assume] Léa Domblatt on the family grave at the Bagneux cemetery in Paris. (our own photo)

Jean died in Paris on April 4, 1957 at the age of 69. He is buried in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris, where he lies alongside a number of other deportees. Jean Domblatt’s name beside a photograph of him and a woman, whom we assume to be his wife Léa, given that he never remarried. The other monument shown in the photos is a memorial to the victims from Jean Domblatt’s hometown of Szydlowiec. It bears the names and photos of some deportees from the town, including Jean. The memorial serves to keep alive the memory of all those who suffered during the Second World War, and to pass on their stories to future generations.

The Memorial to the deportees originally from the Polish town of Szydłowiec, who died at the hands of the Nazis, in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris

(our own photo)

In 1964, his son Max was buried beside him.

Photo of Max on the grave at the Bagneux cemetery in Paris

(our own photo)

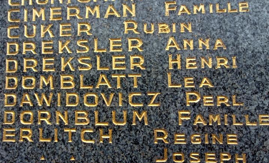

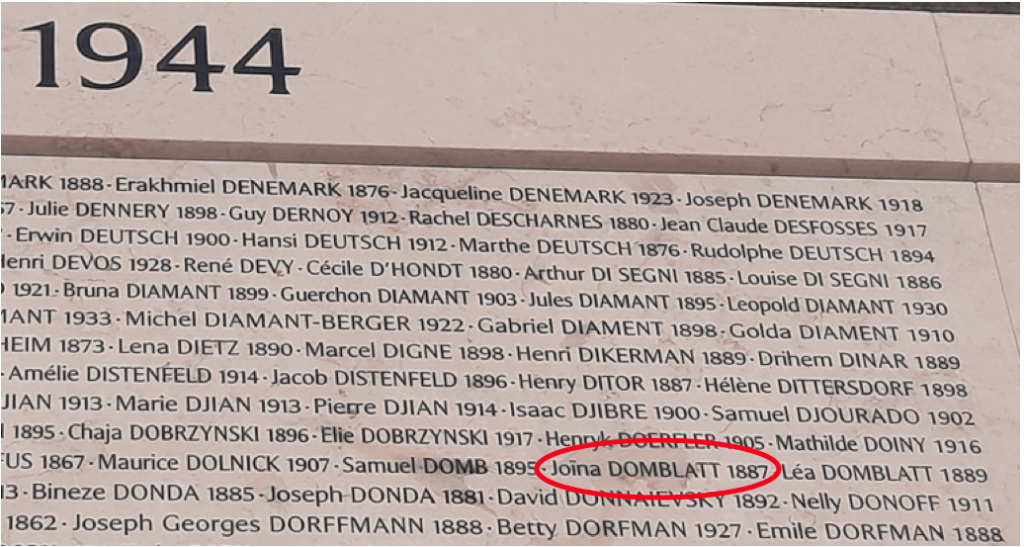

Lastly, Jean’s name is also inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial de Paris, beside those of his parents and the 75,565 other Jews deported from France.

Wall of Names, Shoah Memorial, Paris

(our own photo)

- THE UNRESOLVED GREY AREAS OF JEAN’S LIFE

Despite the wealth of information we were able to gather from the archives, our research and various other sources, many questions remain unanswered.

Firstly, we still have many questions about his life before the war, particularly his childhood, as well as the reasons that prompted his brothers to emigrate to the United States and him to France.

We also have no information on whether Jean Domblatt and his son spent any time together in Auschwitz or Dachau.

Lastly, we have a vast grey area surrounding his life after the war ended.

We have only a few traces of his life in France between 1946 and 1956; he was granted political deportee status on November 27, 1953, and we know the date of his death in 1957. However, this is the only information we have on Jean Domblatt after he returned from the camps.

What happened later in his life? Did he ever testify about what he experienced?

We would like to thank:

- The Convoy 77 team, who kindly sent us most of the records that enabled to retrace Léa Domblatt’s life story and write this biography

- The documentation department at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, for making us welcome and supplying some additional records

- The International Institute for the Memory of the Shoah at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, and the Arolsen Archives in Bad Arolsen, for taking the time to answer our questions and provide us with additional records.

- The Haute Vienne departmental archives service, the Paris archives service, the town hall of the 19th district of Paris, the staff at the Bagneux cemetery and the mayor of Desvres.

- Everyone else, from near and far, who helped us bring this project to fruition.

We would like to express our most sincere gratitude to Yvette Lévy, a Convoy 77 survivor, who very generously invited us into her home to share her story and give us a better understanding of what the Convoy 77 deportees went through. Meeting her and hearing what she had to say was an incredible opportunity that will be remembered as one of the highlights of this project.

Français

Français Polski

Polski