Johanna BUXBAUM KAZDA

For the 11th grade students of class 1C-Euro at the Marcel Pagnol high school in Marseille, France, this year’s goal was to respond to the following question: What was it like to be a woman during the extermination program. To this end, they carried out two investigations, one on Annette Preis, about whom there are numerous archived records available, and one on Johanna Buxbaum Kazda, about whom there are very few.

The students split into groups according to the research to be carried out and then shared their work so as to gain an understanding of the difficulties arising from historical silences. They then came up with additional thoughts during a moving debate, where they positioned themselves according to their opinion on the subjects:

- I) Who was Johanna Buxbaum Kazda?

- II) Historical silences in Johanna Buxbaum Kazda’s life story.

- III) Summary of the moving debate: Should we forget or remember the past?

- IV) Student voices: Why is it important to work on gender history? How does your project help to overcome prejudice?

- V) Screening of the film Les Leçons Persans (Persian Lessons) at the La Baleine movie theater in Marseille

- VI) An exhibition in the school library, in partnership with the 12th grade class B, who worked on an investigation about two women who were deported from Marseilles on Convoy 52: Tauba and Chaya Minska

I) Who was Johanna Buxbaum Kazda?

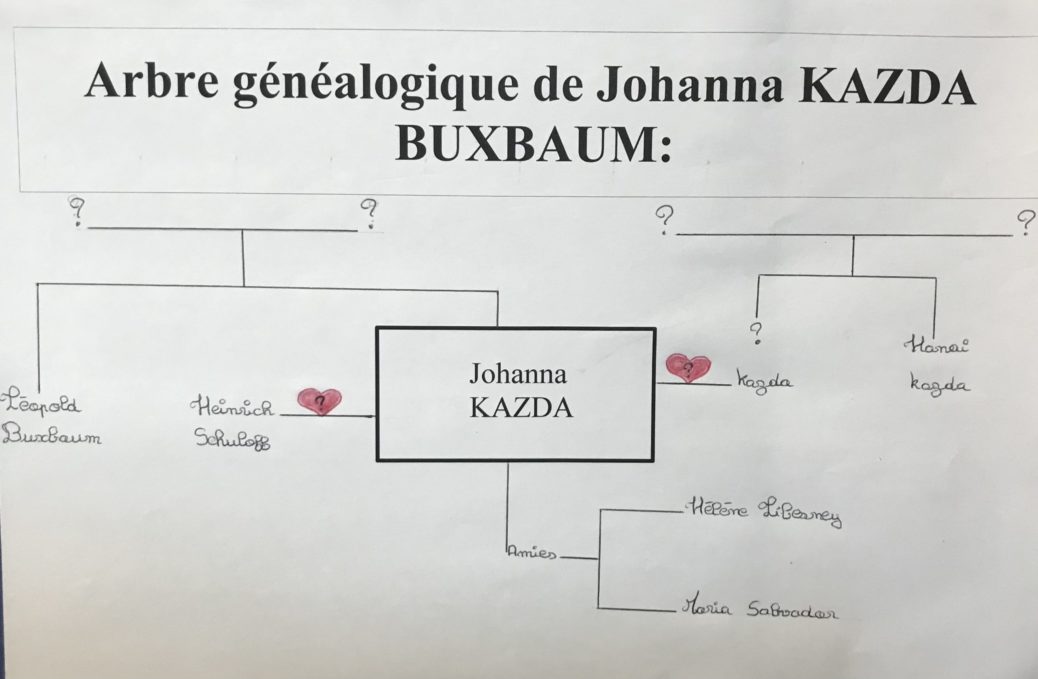

Johanna was born on January 14, 1909. Her birthplace differs according to the sources: Vienna, in Austria [1], or Fiume, which was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1909 but is now in Italy [2].

The cover of a folder on Johanna Kazda,

Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives, Convoy 77 association.

Her surname was Buxbaum [3] but the spelling differs according to the source. It was also spelled Buxbann or Bubaum [4].

As for her family, we have no information at all. However, we are looking for a record linked to the Johanna’s page on the website of the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Yad Vashem [5]. This list, dated 1938, is entitled “transported from Am Steinhof”, the former name of a district of Vienna in which there was a hospital [6] and it includes the name of Leopold Buxbaum, who was Jewish.

Source: The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names

The DOEW (Documentation Center of the Austrian Resistance) online archives also mention this person [7]. In the years following the Anschluss, which took place in 1938, the “Am Steinhof” sanatorium and retirement home, currently the Otto Wagner Hospital, became the Viennese hub of the National Socialist party’s homicidal medical system, which cost the lives of at least 7,500 Steinhof patients: From 1940 to 1945, there was a so-called “children’s ward” in the grounds of the facility which was called “Am Spiegelgrund”, in which about 800 sick and disabled children and young people died. In 1940-41, more than 3,200 patients were transferred from the facitlty to Hartheim Castle, near Linz, where they were murdered as part of the Nazi “T4 Aktion” program. Then after the war, more than 3500 patients fell victim to starvation and infections [8]. We think the number written in front of Leopold’s name was his age, which would make him 18 years old in 1938, and that he may have been Joanna’s brother.

Family tree drawn by Louna and Emna

We found a trace of Johanna in a record from the Paris prefecture.

She arrived in France in 1938 [9]. She may have left Austria in the wake of the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by the Third Reich, which heralded the intensification of persecution and deportation of the Jews. When she first arrived in France, Johanna stayed in a hotel: the Ambassadeur, which is on Boulevard Haussmann in Paris and is still in operation today[10]. We believe that this was a hotel where Austrians such as Johanna, who had fled from the Third Reich, congregated.

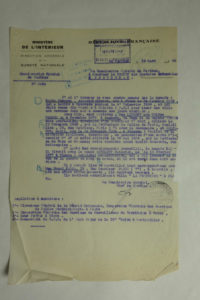

We next catch up with Johanna via the special commissioner of Perthus, who wrote to the Prefect of the Pyrénées Orientales department of France on 15 March, 1940, with some information to be passed on to the director general of the national security in Paris[11]. He was watching Johanna, who had gone to Palalda, in the Pyrenees Orientales department, near the Spanish border, to stay in a rented villa. Some other people arrived at the same time as Johanna, including a Mrs. Hélène Libesny, who also went by the name of Fremud, who did not work, and who was born on November 6, 1879 in Temberg. Her parents are thought to have been Hugo and Sophie Tennkr.

Hélène had previously been living at 19 rue Monsieur in Paris with a woman named Maria Salvador, who was born on November 24, 1924 in Fregona, Italy. She was an Italian domestic servant and held an identity card bearing the number 37 ac 45033, which was issued on May 28, 1939 by the Tarn-et-Garonne prefecture since she was living on rue Moissegaise in Caussade at the time.

Letter from the special commissioner of Perthus, to the Prefect of Pryénées Orientales department, dated March 15, 1940, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives, Convoy 77 association.

Johanna lived with Heinrich Schuloff, who was born on February 15, 1877 in Vienna, Austria. He was interned in the Latus camp for two months at the beginning of the war. He was listed as ex-Austrian, so had perhaps become a French citizen by naturalization. He was a lawyer who, before the Second World War, had lived in Paris. [12].

In a personal information form about Johanna from the Pyrénées Orientales departmental archives, it is stated that she was “married” [13] but to whom, we do not know. It is possible that she first married a Mr. Kazda and then began a relationship with H with Heinrich Schuloff. She would appear to have kept in touch with her in-laws, the Kazda family, however, because the special commissioner of Perthus was also monitoring Johanna’s mail. She was writing to Hanai or Hansi Kazda who, like Hélène Libesny, lived at 19 rue Monsieur in the 7th district of Paris. Johanna probably networked in Paris and then moved to the south of France, where there was apparently a cluster of Austrians.

From Mr. Guillaume Nicolaï, Pyrénées Orientales departmental archives, personal file, number 44 608 and number 44 499, file ref. 1260W16, email received in March 2023.

We also note from this record that Johanna’s first name was listed as Jeanne. She was interned in the Rivesaltes camp on August 28, 1942 according to one record, but on September 29, 1942 according to the other. She was released on September 30, 1942. Rivesaltes became a transit camp for Spanish migrants, gypsies and foreign Jews. According to the Rivesaltes camp memorial website [14] , it became the inter-regional detention facility for Jews in 1942, the “Drancy” of the southern zone. Johanna was one of 5000 Jews interned there between August and November 1942, all victims of the policy of exclusion of undesirable foreign nationals adopted by the Vichy regime in 1940. On one of the records [15], her date of birth has been changed to November 14, 1909. It states that she was a Protestant and was liberated in Saint Paul de Fenouillet. Johanna probably escaped deportation initially with the help of relief organizations, such as the Red Cross or the YMCA, and also Paul Corazzi, the Prefect’s official representative. This would explain the change of her religion from Jewish to Protestant and of her first name from Johanna to Jeanne. She may also have decided to call herself Jeanne in order to fit in more easily or she may have become a French citizen.

We decided to call the Rivesaltes camp memorial. We were given an email address, to which we sent our hypotheses and requests for information, but they had no further details.

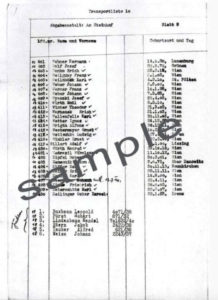

We found traces of Johanna in a number of records from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts and the Arolsen archives [16] .

From Mr. Axel Braisz, Arolsen archives, 1.1.9.9 / 11191113

dated July 31, 1944, mail received in January 2023.

Johanna’s first name and surname appear on the list of people deported on Convoy 77, which left Drancy on July 31, 1944. From the Shoah Memorial website, we discovered that Johanna and Heinrich were living in Saint Paul de Fenouillet in the Pyrénées Orientales department when they were arrested. Johanna was then transferred to Drancy camp. We think that she was aware that she was about to be arrested in Perpignan because she had 3070 francs and a bracelet with a gold charm on her, according to receipt number 6101 from search log book 153 from Drancy camp, issued on July 2, 1944 [17]. This might have made it possible for her buy her way out, and escape, or could potentially have been bartered. We also found the name of Heinrich Schuloff. His receipt number from the Drancy camp, issued on July 2, 1944, is 6102, which is just after Johanna’s log number, also from log book number 153. He had 4468 francs on him at the time [18]. They must therefore have arrived at Drancy together.

Johanna and Heinrich were both deported on Convoy 77 to the Auschwitz Birkenau concentration and extermination camp on July 31, 1944.

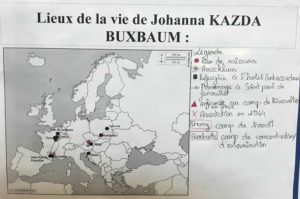

Map of the places in Johanna’s life, drawn by Chérine, Kélia et Razikina.

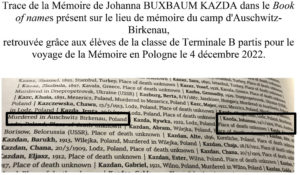

Johanna died in Auschwitz, according to both the Shoah Memorial archives [19] and the entry in the Book of Names, which the 12th grade students from our high school viewed during their trip to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in Poland on December 4, 2022. Johanna’s name is also inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris [20].

II) The historical silences in Johanna Buxbaum Kazda’s life story

1) What does it mean to be a woman?

Being a woman can mean putting your life on the line for the country that doesn’t even care about you.

Being a woman can mean being raped.

Being a woman can also mean being portrayed as a French woman who sleeps around but at the same time has to rival with men and their masculinity.

Being a woman can mean being killed because children do not want to be separated from their mother.

2) What are “historical silences”? What are the silences in Johanna’s life story ?

There are usually written records about people who have contributed to the technical or political development of their country or of the world. But in this case, such written traces have been covered up, destroyed or even altered. This is what is known as historical silence. An example of this is the work of Marie Curie who designed the “Petites Curies”, which were mobile X-ray vehicles first used during the First World War.

In Johanna’s case, the silence is mainly due to the lack of information about her family, her work and the places where she lived. We also know nothing of her life during or after she migrated to France, since there are no witnesses.

We are also aware that many archives have been burned or altered. This has an impact on the writing of her story, in the spelling of her name, for example.

3) What are the specific types of violence experienced by deported women, and by Johanna?

Johanna was forcibly arrested and had her possessions taken away from her, including her money and jewelry, and then she was deported.

Women at that time suffered sexual violence such as rape and forced prostitution, as well as sexism, with fewer rights and inequality of living standards as a result of the armed conflict.

4) What are some of the psychological and physical impacts specific to women?

Women experienced lower morale and social exclusion, suffered cruel abortion-related experiments, and faced hunger, thirst, and fatigue in the camps.

Rape causes significant trauma. Much-loved family members, such as husbands and children, died, and this led to intense grief.

Women’s working conditions were very harsh.

5) What were the roles of women involved in or opposed to the extermination process?

After the war, some women took on the role of suppressing the testimonies of women, who were neglected or ignored. Many women were victims of rape and as such, of the patriarchal system.

Women participated in the resistance because they were determined to fight for freedom, as was the case with Emilienne Moreau-Evard. She set up a first-aid post in her home, working twenty-four hours a day transporting and caring for wounded people.

In order to rescue an English soldier caught in the crossfire, she did not hesitate to leave her house, armed with grenades, and with the help of some English soldiers, she managed to put two German soldiers who were holed up in a nearby house out of action. A short time later, when the house was surrounded , she grabbed a revolver and shot two enemy soldiers through the door..

Women were also actively involved in enforcement, such as the 500,000 German women who were part of the German army: the Wehrmacht. There were about 3500 women supervisors in the camps. Women tended not to be involved with the actual extermination process, but that does not absolve them from responsibility for the executions: they were torturers and witnesses in the death camps.

Some women were also forced into prostitution by the primarily male armies.

Lastly, many women have witnessed and contributed to the fight against historical silence

6) In what ways does your project contribute to keeping the memory of the deportation, and Johanna, alive?

Through our project, we have brought to light the stories of people who have been cast aside, either on account of their gender or their ethnicity, or both.

In addition, despite the time that has elapsed since these people were deported, we have learned more about them, have been moved by the experience and can share their stories with our loved ones, thus helping to keep the memory of them alive.

7) What adjectives could be used to describe Johanna’s life as a deportee?

Johanna can be described as independent and courageous, since she put herself in danger through writing letters to family and friends at a time when the authorities were monitoring her activities simply because she was Jewish.

III) Summary of the moving debate: Should we forget or remember the past?

IV) Student voices: Why is it important to work on gender history? How does your project help to overcome prejudice?

V) Screening of the film Les Leçons Persans (Persian Lessons) at the La Baleine movie theater in:

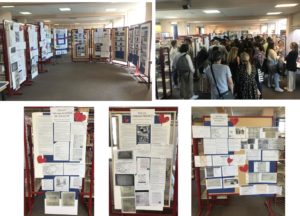

VI) The exhibition in the school library, in partnership with the 12th grade class B, who worked on an investigation about two women who were deported from Marseilles on Convoy 52: Tauba and Chaya MINSKA :

=> You can view all the students’ shared work on the theme “Being a woman during the extermination process”, in French, on this padlet .

This investigation was carried out by: Chérine, Razikina, Emna, Kélia and Louna from 11th grade class 1C, with the guidance of their history and geography teacher Morgane Boutant.

Congratulations to the students for their hard work and enthusiasm!

Sources for the investigation:

[1] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.phpq=kazda&spec_expand=1&sort_define=score&sort_order=1&rows=10&start=0 , From Mr. Guillaume Nicolaï, Pyrénées Orientales departmental archives, person files numbers 44 608 and 44 499 , file ref. 1260W16, email received in March 2023. From Y Grondin, Paris police department archives, collection 325W, Foreigners’ file on microfiche no. 328 W, email received in January 2023.

[2] Cover of the folder on Johanna Kazda, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives, Convoy 77 association.

[3] From Y Grondin, Paris police department archives, collection 325W, Foreigners’ file on microfiche no. 328 W, email received in January 2023.

[4]https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.phpq=kazda&spec_expand=1&sort_define=score&sort_order=1&rows=10&start=0

[5]https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=fr&itemId=4963987&ind=2

[6]https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=fr&itemId=4963987&ind=2

[7]https://www.doew.at/result

[8] https://www.doew.at/address/15725/

[9] From Y Grondin, Paris police department archives, collection 325W, Foreigners’ file on microfiche no. 328 W, email received in January 2023.

[10] From Y Grondin, Paris police department archives, collection 325W, Foreigners’ file on microfiche no. 328 W, email received in January 2023.

[11] Letter from the commissioner at Perthus to the Prefect of the Pyrénées Orientales department dated March 15, 1940, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives, Convoy 77 association.

[12]https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=fr&itemId=7111403&ind=3

[13] From Mr. Guillaume Nicolaï, Pyrénées Orientales departmental archives, personal file, number 44 608 and number 44 499, file ref. 1260W16, email received in March 2023.

[14] https://www.memorialcamprivesaltes.eu/index.php/lhistoire-du-camp-de-rivesaltes

[15] From Mr. Guillaume Nicolaï, Pyrénées Orientales departmental archives, personal file, number 44 608 and number 44 499, file ref. 1260W16, email received in March 2023.

[16] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.phpq=kazda&spec_expand=1&sort_define=score&sort_order=1&rows=10&start=0

, From Mr. Axel Braisz, Arolson Archives, 1.1.9.9 / 11191113 dated July 31, 1944, email received in January 2023.

[17] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/zoom.php?code=310591&q=id:p_238009&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

[18] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/zoom.php?code=232252&q=id:p_245469&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

[19] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=johanna%20kazda&spec_expand=1&start=0

[20] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=johanna%20kazda&spec_expand=1&start=0

Sources on “historical silences”:

- Titiou LECOQ, Les grandes oubliées : Pourquoi l’Histoire a effacé les femmes , l’Iconoclaste, Paris, 2021. Chapitre 15 : Deuxième Guerre mondiale : le rôle des femmes minimisé.

- Michelle PERROT, Les femmes ou les silences de l’Histoire, Flammarion, Paris, 2020. Quatrième de couverture.

- Association MNEMOSYNE, Coordination Geneviève DERMENJIAN, Irène JAMI, Annie ROUQUIER, Françoise THEBAUD, La place des femmes dans l’histoire, une histoire mixte , Belin, Paris, 2010. Chapitre : Femmes et hommes dans les guerres, les démocraties et les totalitarismes (1914-1945).

- Simone de BEAUVOIR, Le deuxième sexe, Tome I, Gallimard, Paris, 1949. Quatrième de couverture.

- Jo-Ann OWUSU, Les menstruations et l’holocauste History Today, numéro 69, mis en ligne le 5 mai 2019.

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/menstruation-and-holocaust - Isabelle ERNOT, Le genre en guerre . « Exécutrices, victimes, témoins », Genre & Histoire, numéro 15, mis en ligne le 30 septembre 2015.

https://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/2218 , - Isabelle ERNOT, Le genre en guerre : « Women and/in the Holocaust » : à la croisée des Women’s-Gender et Holocaust Studies (Années 1980-2010) », Genre & Histoire, numéro 15, mis en ligne le 30 septembre 2015 .

http://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/2223

> Consult the original version of this biography of Johanna KAZDA in french.

Français

Français Polski

Polski