Annette PREIS

For the 11th grade students of class 1C-Euro at the Marcel Pagnol high school in Marseille, France, this year’s goal was to respond to the following question: What was it like to be a woman during the extermination program. To this end, they carried out two investigations, one on Annette Preis, about whom there are numerous archived records available, and one on Johanna Buxbaum Kazda about whom there are very few.

The students split into groups according to the research to be carried out and then shared their work so as to gain an understanding of the difficulties arising from historical silences. They then came up with additional thoughts during a moving debate, where they positioned themselves according to their opinion on the subjects:

- I) Who was Annette Preis?

- II) Historical silences in Annette Preis’ life story.

- III) Summary of the moving debate: Should we forget or remember the past?

- IV) Student voices: Why is it important to work on gender history? How does your project help to overcome prejudice?

- V) Screening of the film Les Leçons Persans (Persian Lessons) at the La Baleine movie theater in Marseille

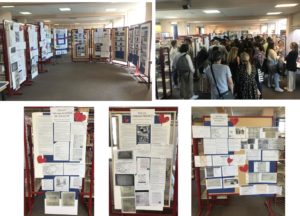

- VI) An exhibition in the school library, in partnership with the 12th grade class B, who worked on an investigation about two women who were deported from Marseilles on Convoy 52: Tauba and Chaya Minska

I) Who was Annette Preis?

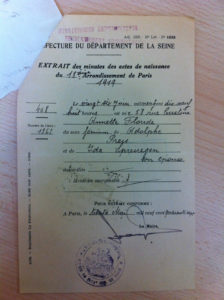

Annette was born on June 26, 1919 in the 18th district of Paris, France. Her middle name was Floride. Her parents were Adolphe Preis, who was born in Reims on February 7, 1884 and Ida Spreiregen, who was born in Warsaw, Poland on July 27, 1892 [1]. Before the war, Annette lived with her parents at 51 rue Mathurins in the 8th district of Paris [2] [3]. She was Jewish. She had no criminal record.

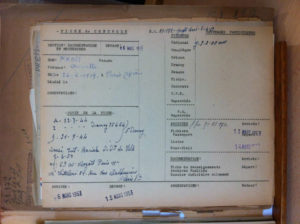

Birth certificate issued in the 18th district of Paris on May 30, 1947, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives, Convoy 77 association.

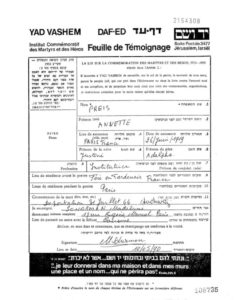

We know that she had a cousin, Madeleine Opalek Scherman or Schermann [4] .

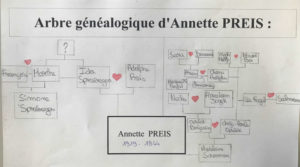

Madeleine requested a search on Annette and some other members of her family, which enabled us to put together Annette’s family tree.

Annette’s family tree, drawn by Kayna and Eva.

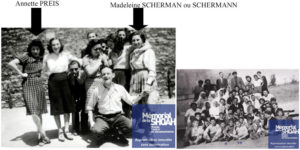

Madeleine and Annette are both featured in two photos on the Shoah Memorial website [5][6] ,

Source: Shoah Memorial online resources

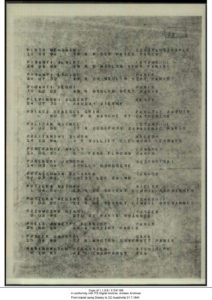

UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) record of staff requesting yellow stars, Annette’s name and surname are included. She asked for 8 stars for 3 people [7].

List of personnel requesting yellow stars dated September 23, 1942, Microfilm,

Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

She worked for the UGIF as a teacher. The address of the school was 8-9 rue Vauquelin, Paris. It was a residential school, so she lived there.

Another address associated with Annette is 69 avenue Mozart in the 6th district of Paris. This was noted in the search book when she arrived at Drancy camp, search log number 157, receipt number 6538 [8] and in checklists from the status division [9]. Perhaps she gave a false address in order to shield her parents when she was arrested? Or might it have been an address she was familiar with, perhaps that of her lover? A Mr. Wittelson reported her missing on September 7, 1945 in Paris, giving her parents’ address, which was 51, rue des Mathurins, in the 8th district [10].

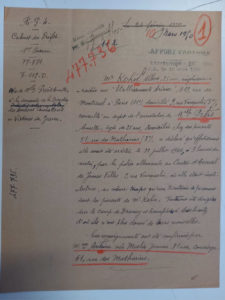

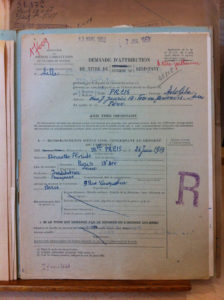

Request for research on a deported person made by Mr. Wittelson on September 7, 1945,

Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

He could be her boyfriend or her roommate. He gave a description of Annette: a tall, slim brunette, which is consistent with a further source: an archive in the form of a photograph on the Shoah Memorial website [11]. He applied for a deportation search on Annette in September 1945 with a deportation date of July 31, 1944. He did not know if Annette had actually arrived in Auschwitz.

Annette’s father, Adolphe, recalls her arrest: Annette was arrested on July 22, 1944 with a group of 200 children and all the staff. Another source, 62-year-old Mr. Robert Geismann, [12] a member of the French Consistory, who was arrested on April 2, 1953, said that Annette was affiliated with the UGIF but that he did not know her personally. A further witness, Mr. Albert Kohn [13], also mentions Annette’s arrest, saying that her parents were arrested at the same time.

Y. Grondin at the Paris Police Headquarters archives service sent us Mr. Albert Kohn’s testimony, dated March 10, 1950, from the General Information database 77W and 149 W. Email received in January 2023.

The time of the arrest is given as 3 a.m. It was carried out by the German police at the home for girls at 9 rue Vauquelin. Annette was one of about thirty people who were taken to Drancy camp. This information was confirmed by Mrs. Joanna Antoine, née Meslin, who was 81 years old and the janitor at 51 rue Mathurins. We typed the address 9 rue Vauquelin into Google maps and we were able to identify a memorial plaque for the victims of the roundup, including Annette. We then decided to call the phone numbers listed for this location, but the people we spoke to told us that they had no documentation that would help us.

Plaque in memory of the Jewish girls and adults arrested on July 21, 1944 at 9, rue Vauquelin, in the 5th district of Paris. Source: The French Resistance museum website

The roundup on rue Vauquelin took place on the night of 21-22 at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris, at the headquarters of the Jewish Seminary of France which was in a UGIF center for young girls, where there were 33 Jewish girls staying. Many of them were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on Convoy 77, the last large convoy to leave Bobigny railroad station. They were rounded up and deported together with the school staff. A Wikipedia article lists Annette Preis as one of the victims [14] but her address is incorrect: it is given as 69 avenue Mozart in the Bouches du Rhône department of France. It does however match the Paris address that Annette gave when she was arrested, perhaps in order to shield her relatives in the city.

Annette was arrested on grounds of her “race” [15]. She was interned in Drancy on July 22, 1944 and given the number 25464. We suppose that she must not have been aware that she was about to be arrested because according to the search log [16] she only had 32 francs on her when she arrived in Drancy camp, which was run by the SS officer Aloïs Brunner. His responsibilities made him an important participant in the Final Solution, together with Adolf Eichmann, who was in charge of logistics.

We then retraced Annette’s steps by means of various records, which caused some confusion. She was reported as having died on July 31, 1944 in Drancy according to two records dating from 1949 [17] et 1952 [18] but was “transferred” to Auschwitz according to two other records dating from 1950 [19].

In addition, on a Shoah Memorial database on which crosses and circles are displayed in front of the deportees’ names, there is no symbol beside Annette’s name[20], so perhaps she was not on Convoy 77 from Drancy to Auschwitz after all. Or might she have died on the journey? According to Auschwitz survivor Yvette Levy’s testimony [21], the travelling conditions were appalling: there was hardly any water, poor sanitary conditions and it was terribly hot.

Annette is also listed in the Arolsen archives as having traveled from Drancy to Auschwitz, but with no cross in front of her name [22].

Mr. Axel Braisz, from the Arolsen Archives service sent us this list record no, 1.1.9.9 / 11191160 dated July 31, 1944. Email received in January 2023.

In 1948, Annette’s parents, Ida and Adolphe Preis, moved to 14, rue des Marchands in Fère-en-Tardenois in the Aisne department of France [23].

Mr. Raphaël Baumard, from the Aisne departmental archives sent us this Deed of Purchase in the names of Adolphe Preis and Ida Spreiregen, dated January 29, 1948, ref. 4 Q 1/ 301. Email received in January 2023.

On March 13, 1952, one of Annette’s parents applied for a death certificate for their daughter and made a compensation claim for the loss of her property [24]. We think her belongings must have been confiscated, which is why she had to stay at the UGIF school.

A prescription shows that her mother, Ida, had eye problems and a heart condition, and she wanted the compensation to pay for her treatment [25]. Her father, Adophe, received a certificate transfer of ownership of her estate on January 30, 1950 [26].

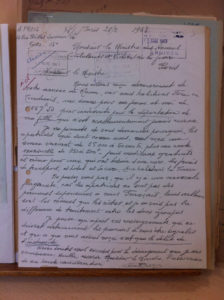

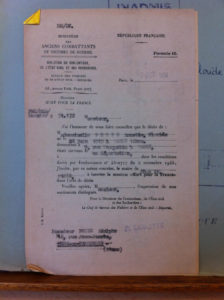

In 1967, Ida Spreiregen, who was living at 14 rue Brillat Savarin in the 13th district of Paris, asked for reparations for the loss of her daughter, who had been deported for political reasons, in accordance with a decree issued on August 29, 1961 as part of the 1960 Franco-German agreement on compensation for victims. The Association of Auschwitz Deportees from the camps in Upper Silesia endorsed her request [27]. In her application, Ida argued that stateless people and other deportees were dealt with differently [28].

Ida’s letter to the Minister of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War, dated February 26,1963,

Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

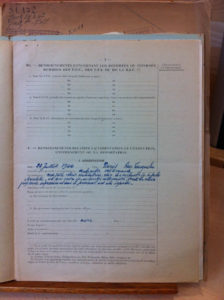

In addition, an application was made for Annette to be granted the status of deported Resistance fighter [29] but this was turned down.

Annette’s father’s application for the status of deported Resistance fighter, dated March 11, 1952, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

Annette’s father’s application for the status of deported Resistance fighter, dated March 11, 1952, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

Did Annette try to escape? Did she try to save or hide some of the children at the school? A few children were saved thanks to the courage of others. Two escapes were recorded in reports dating from November 29, 1942 and January 16, 1943, which are available on the Shoah Memorial website [30]. Her father explained the circumstances under which the status was awarded. He mentions the fact that his daughter was the Jewish children’s teacher and that the staff were arrested together with the children them during the roundup. [31]. Annette was granted the status of “Died for France” on October 2, 1954 [32].

Decision issued by the head of the office of Records and deported civilians, dated April 7, 1954, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

The status of “Died for France” was granted in certain circumstances, in accordance with articles L488 to L492bis of the French law on military invalidity pensions and victims of war [33].

Annette was granted the status of Political Deportee in 1994 [34].

Lastly, Annette’s first name and surname are inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris [35].

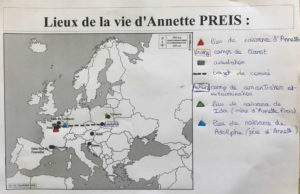

Map of the places in Annette’s life drawn by Cécile, Léane, Elyes, Antoine and Kilian.

II) The historical silences in Annette Preis’ life story

1) What does it mean to be a woman?

Being a woman often involves facing challenges and gender-based inequality while still being able to build an identity, forge relationships and achieve personal goals. Being a woman can also involve being part of a movement to fight for equality and for the recognition of women’s contribution to society.

Being a woman means being able to choose one’s gender according to one’s own preferences and according to what is most appropriate for one’s body, which is not necessarily tied to one’s sex as determined at birth.

2) What are “historical silences”? What are the silences in Annette’s life story?

Historical silences can be defined as omissions or gaps in historical narratives in which events, groups or individuals are ignored, minimized or erased. These silences can be the result of a number of factors such as prejudice, discrimination, censorship policies, manipulation of collective memory, editorial choices or educational practices. All these factors can contribute to some people being marginalized or rendered invisible. In the case of women, such silence is characterized by a lack of communication about combat successes or technical achievements and their being omitted from historical accounts.

This silence can be heard, however, when there are witnesses or survivors of these events and when historians such as Michelle Perrot bring them to light.

The silences in the story of our deported woman involve the circumstances and exact date of her death, her home address and her friends and relations, whom she tried to protect by muddying the waters.

3) What are the specific types of violence experienced by deported women, and by Annette?

There are many different types of violence, such as:

- Physical violence, such as mutilation, forced sterilization, mutilated reproductive systems, torture and involuntary abortion.

- – Poor living conditions and lack of food in the camps.

- Rape.

- Roundups.

- Forced prostitution.

- Humiliation, such as when women were shorn and shaved towards the end of the Second World War.

- Murder, execution, being a victim of genocide.

Annette was subjected to various types of violence, such as the round-up, deportation, and psychological abuse, including the eradication of her social life.

4) What are some of the psychological and physical impacts specific to women?

The psychological effects are: the anguish of being separated from one’s loved ones, mental illness, depression, anxiety and fear, stigmatization, not being listened to when people would rather forget, lack of support.

The physical consequences are death, illness, and attempted suicide.

5) What were the roles of women involved in or opposed to the extermination process?

Women participated in the extermination process. Their stories are glossed over, but their participation was very real. For example, 500,000 German women were recruited into the Wehrmacht. They also worked in the camps as auxiliaries, nurses and doctors who took care of the soldiers, and as camp guards and supervisors.

There were also women resistance fighters. They could have been, for example, network leaders or liaison officers who distributed newsletters and leaflets.

Women participated in the resistance because they were determined to fight for freedom, as was the case with Emilienne Moreau-Evard. She set up a first-aid post in her home, working twenty-four hours a day transporting and caring for wounded people.

In order to rescue an English soldier caught in the crossfire, she did not hesitate to leave her house, armed with grenades, and with the help of some English soldiers, she managed to put two German soldiers who were holed up in a nearby house out of action. A short time later, when the house was surrounded, she grabbed a revolver and shot two enemy soldiers through the door.

Lastly, many women have witnessed and contributed to the fight against historical silence.

6) In what ways does your project contribute to keeping the memory of the deportation, and Annette, alive?

Our project aims to revive the memory of the wartime deportations by raising public awareness and helping people to understand its impact and consequences. We pay tribute to the victims in order to break the silence.

Our work provides new insights into Annette’s story, and serves as a point of reference. We contribute to keeping her legacy alive by searching for the truth.

7) What adjectives could be used to describe Annette’s life as a deportee?

Annette was courageous, in that she did not hesitate to lie to protect her loved ones. She must also have been caring and altruistic, given the nature of her work.

III) Summary of the moving debate: Should we forget or remember the past?

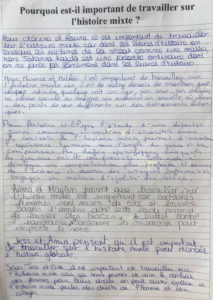

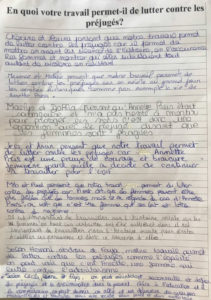

IV) Student voices: Why is it important to work on gender history? How does your project help to overcome prejudice?

V) Screening of the film Les Leçons Persans (Persian Lessons) at the La Baleine movie theater in Marseille

VI) The exhibition in the school library, in partnership with the 12th grade class B, who worked on an investigation about two women who were deported from Marseilles on Convoy 52: Tauba and Chaya Minska

=> You can view all the students’ shared work on the theme “Being a woman during the extermination process”, in French, on this padlet .

This investigation was carried out by: Kinda, Antoine, Elyes, Amin, Kilian, Léane, Cécile, Eva, Djibril, Javier, Axel, Milo, Kyana, Yanis, Jess, Adrien, Hernani, Fayani, Abdou, Tess, Elisa, Hilma, Dalhia, Maëlys, Maylis, Maxence, Mathéo, Léa, and Thibault from 11th grade class 1C, with the guidance of their history and geography teacher Morgane Boutant.

Congratulations to the students for their hard work and enthusiasm!

Sources for the investigation:

[1] Mr Raphaël Baumard, from the Aisne departmental archives sent us this Deed of Purchase in the names of Adolphe Preis and Ida Spreiregen, dated January 29, 1948, ref. 4 Q 1/ 301. Email received in January 2023.

[2] Birth certificate issued in the 18th district of Paris on May 30, 1947, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[3] Report of the investigation carried out by the Police Department dated April 18, 1953, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[4] https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr&s_id=&s_lastName=preis&s_firstName=annette&s_place=&s_dateOfBirth=&cluster=true

[5] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=scherman&spec_expand=1&start=12

[6] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=id:385114

[7] List of staff requesting yellow stars dating from September 23, 1942, Microfilm, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[8] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/zoom.php?code=308643&q=id:p_248661&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

[9] Form from the status control department dated July 20, 1953, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[10] Request for research on a deported person made by Mr Wittleson on September 7, 1945, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[11] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=id:385114

[12] Report of the investigation from the Police Department Headquarters dated April 18, 1953, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[13] Y. Grondin at the Paris Police Headquarters archives service sent us Mr. Albert Kohn’s testimony, dated March 10, 1950, from the General Information database 77W and 149 W. Email received in January 2023.

[14] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rafle_de_la_rue_Vauquelin

[15] Missing persons certificate from the Ministry of Veterans and War Victims dated July 9, 1947, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[16] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/zoom.php?code=308643&q=id:p_248661&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

[17] Response from the Department of Veterans and War Victims to the missing persons request, dated March 7, 1949, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[18] Death certificate dated March 8, 1952, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[19] Letter from the ITS to the Department of Veterans Affairs dated October 11, 1950, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[20] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/zoom.php?code=228597&q=id:p_248661&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

[21] https://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/yvette-dreyfuss/

[22] From Mr Axel Braisz at the Arolsen Archives, file ref. 1.1.9.9 / 11191160 dated July 31, 1944, mail received in January 2023.

[23] Mr Raphaël Baumard, from the Aisne departmental archives sent us this Deed of Purchase in the names of Adolphe Preis and Ida Spreiregen, dated January 29, 1948, ref. 4 Q 1/ 301. Email received in January 2023.

[24] Letter sent by Adolphe Preis to the insurance administrator dated March 11, 1952, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[25] Prescription made out by Dr S. Gold dated June 15, 1967, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[26] Letter from Mr. Levindrey acknowledging the requested exemption certificate dated February 3, 1950, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[27] Letter from The Association of Auschwitz Deportees from the camps in Upper Silesia to the Ministry, dated June 26, 1967, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[28] Letter from Ida to the Minister of Veterans and War Victims dated February 26, 1963, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[29] Notification of refusal of the status of “Deported Resistance fighter” and granting of the status of “Political deportee” by the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, dated April 7, 1954, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[30] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=id:613028

[31] Application for the granting of the status of Resistance fighter filed by Annette’s father, dated March 11, 1952, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[32] Notification of decision issued by the head of the office of Files and Deported Civil Status dated April 7, 1954, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[33] https://www.memoiredeshommes.sga.defense.gouv.fr/fr/article.php%3Flarub%3D24%26titre%3Dmorts-pour-la-france-de-la-premiere-guerre-mondiale

[34] Cover of the folder with the inscription ” Political deportee ” dated April 1994, Victims of contemporary conflicts archive, Convoy 77 association.

[35] https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=annette%20preis&spec_expand=1&sort_define=&sort_order=&rows=&start=0

Sources “les silences de l’histoire”:

- Titiou LECOQ, Les grandes oubliées : Pourquoi l’Histoire a effacé les femmes , l’Iconoclaste, Paris, 2021. Chapitre 15 : Deuxième Guerre mondiale : le rôle des femmes minimisé.

- Michelle PERROT, Les femmes ou les silences de l’Histoire, Flammarion, Paris, 2020. Quatrième de couverture.

- Association MNEMOSYNE, Coordination Geneviève DERMENJIAN, Irène JAMI, Annie ROUQUIER, Françoise THEBAUD, La place des femmes dans l’histoire, une histoire mixte , Belin, Paris, 2010. Chapitre : Femmes et hommes dans les guerres, les démocraties et les totalitarismes (1914-1945).

- Simone de BEAUVOIR, Le deuxième sexe, Tome I, Gallimard, Paris, 1949. Quatrième de couverture.

- Jo-Ann OWUSU, Les menstruations et l’holocauste History Today, numéro 69, mis en ligne le 5 mai 2019.

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/menstruation-and-holocaust - Isabelle ERNOT, Le genre en guerre . « Exécutrices, victimes, témoins », Genre & Histoire, numéro 15, mis en ligne le 30 septembre 2015.

https://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/2218 , - Isabelle ERNOT, Le genre en guerre : « Women and/in the Holocaust » : à la croisée des Women’s-Gender et Holocaust Studies (Années 1980-2010) », Genre & Histoire, numéro 15, mis en ligne le 30 septembre 2015 .

http://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/2223

> Consult the original version of this biography of Anette PREIS in french

Français

Français Polski

Polski