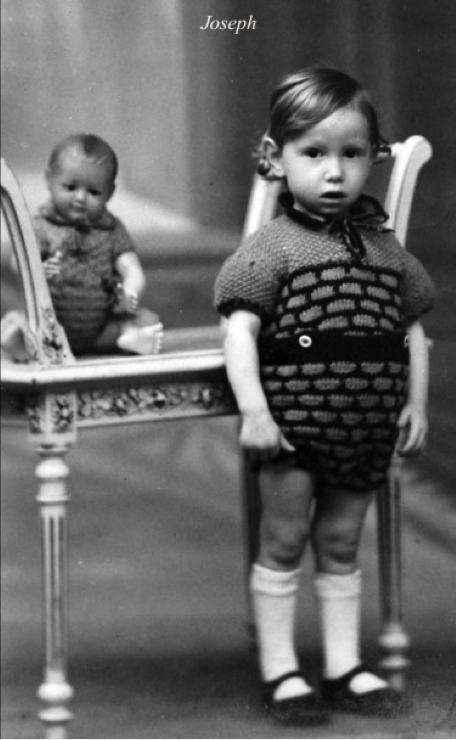

Joseph APEL

“We have not forgotten here either” was the theme that Damien Bressolles, a history and geography teacher at the Jean Bouin high school in Saint-Quentin, in the Aisne department of France, chose for his 12th grade health and social sciences and technologies baccalaureate students during the 2023-2024 school year.

Conscious of the fact that there had never been any historical research into Jewish community in Saint-Quentin, and that Holocaust remembrance was rarely included in local commemorative events, Mr. Bressolles invited his students to join him in researching and co-writing the story of the Jews in Saint-Quentin during the German Occupation.

The aim of the project was to retrace the journeys of families who fell victim to the Holocaust, as well as those who managed to survive it, in order to reflect as accurately as possible the wide range of paths taken by the local Jewish community.

After a lengthy search for archives in more than twenty departments of France and four different countries, gaining access to private records and collecting personal testimonies, the students and their teacher succeeded in following the journey of some thirty families across France and elsewhere in Europe. We also discussed how the Holocaust can be represented visually. With the help of Ms. Robin, their arts and crafts teacher, the students tried their hand at linocut printing and illustrated the families’ biographies using their own images.

During the 2024-2025 school year, the next generation of 11th grade students at the Jean Bouin high school will continue the project by writing more biographies of Convoy 77 victims, among other tasks. The long-term objective is to compile a book about the lives of the 73 Jewish families who lived in Saint-Quentin before the war. Plans are also afoot to design a memorial trail, and we have asked the Saint-Quentin town council to consider laying some commemorative paving stones. Watch this space…

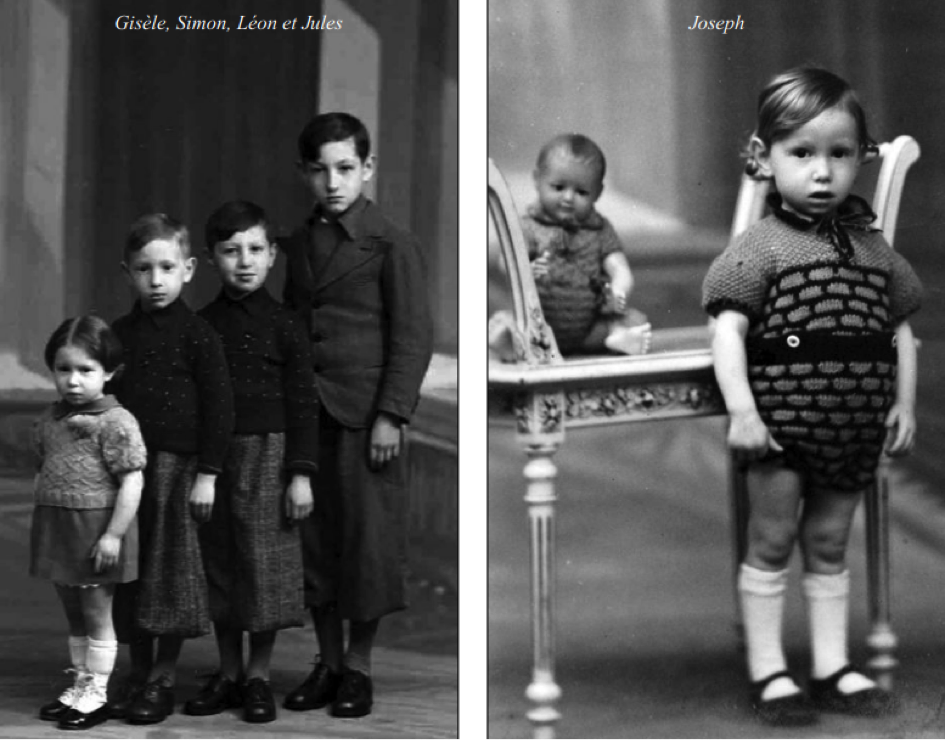

The Apel siblings: Gisèle Apel (1935-1944) and Joseph Apel (1939-1944)

Photos from the Memorial to the Children on the Serge Klarsfeld Foundation website

Gisèle Apel was born on April 28, 1935, and her brother Joseph Apel was born on August 26, 1939, both in Saint-Quentin in the Aisne department of France. Their parents, who were both Polish and Jewish, were Jacob Apel, born June 23, 1896 in Czerwinsk nad Wisla in Poland, and Chaya Apel, née Kopek, born November 14, 1898 in Dzialoszysce, also in Poland. The couple emigrated to France in 1931 and set up home on rue des Bouchers in Saint-Quentin. They had five children: Jules [Jerachmiel] Apel, born on November 26, 1926, in Warsaw, Poland; Léon Apel, born on January 15, 1931, in Warsaw; Simon Apel, born on October 8, 1932, in Saint-Quentin; and then the youngest two, Gisèle and Joseph.

The father, Jacob, worked as a tailor and Chalya did not work outside the home[1]. The children, meanwhile, went to synagogue regularly and attended the synagogue’s Talmudic school[2]. Aside from their religious activities, the family made friends with other members of the Jewish community in Saint-Quentin and enjoyed outings together with other Polish immigrant families[3].

Before the Germans invaded the area in May 1940, the Apel family was evacuated, as was everyone in Saint-Quentin who was unable to leave the town under their own steam. As part of the civilian defense program, most of the families were sent to other areas of France, mainly the Mayenne, Sarthe and Creuse departments[4]. Gisèle and Joseph thus experienced what was known as the exodus. The move was only a temporary respite, however, as the Apel family moved back to Saint-Quentin in late 1940[5]. They then fell victim to the discriminatory policies in force in the occupied zone. On May 9, 1942, the 8th German decree made matters even worse, stipulating: “Jews aged six and over are forbidden to be seen in public unless they wear the Jewish star. The Jewish star is a six-point star, the size of the palm of a hand, outlined in black. It must be made of yellow fabric and bear the inscription “JUIF” (JEW) in black lettering. It must be worn on the left side of the chest, be clearly visible, and be sewn securely onto the outer clothing. Any infringement of this order will be punished by imprisonment and/or a fine. Police sanctions such as internment in a Jewish camp may be added to or replace these penalties. This order will come into force on June 7, 1942. Der Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich”[6] As a result, the Apel family had to go to the sub-prefecture before June 6, 1942, to collect their yellow stars in exchange for clothing ration cards. Joseph, who was under the age of six, was the only member of the family who did not have to wear the star.

After the Vel d’Hiv roundup, which took place in Paris on July 16-17, 1942, the Picardy region also saw mass arrests of foreign Jews. Prior to the roundup, on July 16, 1942, the SIPO-SD, the German security police service, drew up a list of Jews in the three departments in Picardy: Oise, Somme, and Aisne. 79 names were on the list. For the Saint-Quentin area, there were 16 names on the list given to the police, including 4 members of the Apel family[7].

On the mornings of July 18 through July 20, the French police began knocking on people’s doors and making their first arrests. Police reports[8] state that eleven arrests were made during the early hours of the morning. Jacob Appel, the father of the family, his wife and their eldest son Jules [Jerachmiel] were arrested. An aunt, Chaia Apel, was arrested separately, and four people could not be found[9]. The people were arrested at their homes, usually as a couple, and in front of their children.

According to a German order[10], children under the age of sixteen had to be placed in the care of a Jewish organization. If no such organization existed, as was the case here in Saint-Quentin, a Jewish person was assigned to take care of the children, and this had to be reported to the French military police. Mozek Glicensztajn, who lived at 9 rue des Arbalétriers in Saint Quentin[11] was appointed to look after the four youngest Apel children, including Gisèle and Joseph. According to Mozek Glicensztajn’s grandson Michel’s testimony[12] “there was no family connection between the Apel family and the Glicensztajn family, apart from a possible neighborly relationship”. Michèle d’Alméida-Zolty[13] backed up this statement, saying that “the Apel children were left on their own after their parents were arrested, watched over kindly by the Glicensztajn family”. Jacob and Chalya Apel, together with their oldest son, Jules, were deported on Convoy 12 on July 29, 1942, to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they were exterminated.

On October 6, 1942, the German authorities released a new list of foreign Jews to be arrested “with the assistance of the French police, on October 9-10, 1942.”[14]. This roundup was on a different scale, in that children were targeted as well: “All Jewish persons aged three and over, that is to say all persons of both sexes, must be arrested”[15] if their names are on the list. Children under the age of three were to be placed in the care of Jews who were French citizens, and bedridden people were to be handed over to “Jewish charitable organizations or French Jews, to be cared for as an interim measure”[16]. The prefect passed on specific instructions about the timing of the round-up: “The Jews must all be arrested at the same time, i.e. on October 9 and 10. As far as possible, all the arrests should be made by 9-10-42”[17].

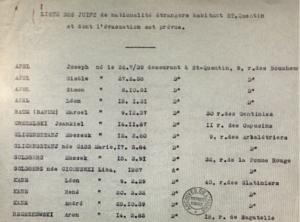

The day before the roundup, the Saint-Quentin military police were given a list of 14 names, including 8 children between the ages of 3 and 14. On October 8 and 9, according to a list drawn up on October 16, 1942[18] 12 of them were arrested.

List of Jews in Saint-Quentin to be evacuated/arrested, October 8, 1942,

Aisne departmental archives, ref. 984 W 139

The children from the Apel and the Kane families arrived at Drancy camp on October 16, 1942[19]. The Apel siblings were soon split up. According to the stamp on the back of their Drancy record card, the two older boys, Léon and Simon, were handed over to the Germans on November 3[20]. The following day, they were deported on Convoy 40 to Auschwitz, and were never heard from again. The surprising thing is that the younger children were not also listed for deportation, although their relationship to their brothers was noted. This strongly suggests that someone on the outside helped the children by ensuring that their names were not put on the Convoy 40 list.

According to their internment record cards, Gisèle Apel (aged 5) was transferred out of Drancy to the Claude Bernard Hospital on November 1, 1942, for health-related reasons, soon followed by Joseph Apel (aged 3) on November 3[21]. On the front of their cards, it says that they were “liberated” on November 25, 1942, and then placed in the care of the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews), which had requested that they be released. This is corroborated by a letter from Léo Israelowich of the UGIF to Chief François at the Paris Police Headquarters, dated November 23, 1942[22] “We are taking the liberty of sending you, herewith, the release orders, signed by SS-Obersturafhurer Roethke […] for the sick children presently in the Claude Bernard Hospital: Gisèle Apel – Joseph Apel”.

The French government founded the UGIF at the behest of the Nazis, supposedly to help the Jewish population in their dealings with the French authorities. However, it also liaised with the Gestapo’s Jewish Affairs Bureau. Although the UGIF is often criticized, its actions can also be regarded as an act of resistance, as the children appeared to be “saved from the clutches of the Germans”. In reality, however, the situation was more nuanced. Between 1942 and 1944, the UGIF saved, evacuated or found safe homes for numerous children. But the children placed in UGIF custody can be split into two categories. Some were classified as “free children”, meaning they had never been detained and their names were not on any lists. Such children were therefore easier to “save”. The second group were “blocked children”, meaning that they had been arrested or detained at some point, their names were on Nazi lists. The UGIF was not allowed to release them, which made its task much more difficult. It thus appears that although the UGIF staff resisted the Nazis by intervening on behalf of the Apel children, in reality, their hands were tied and all they could do was delay their deportation.

When children’s parents had been deported so could no longer care for them, many were placed in children’s homes in and around Paris. Although the UGIF managed such homes, they were actually controlled by the Germans. Gisèle and Joseph Apel were placed in a former clinic that had been converted into a UGIF shelter for younger children at 67 Rue Edouard Nortier in Neuilly-sur-Seine, to the west of Paris[23]. They spent two years there.

In July 1944, as the Allied troops were approaching, the atmosphere in Paris was very tense. Alois Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, decided to launch one final, huge roundup. Between the night of July 21/22 and July 25, 1944, the Gestapo arrested 250 children who were staying in UGIF homes in and around Paris and took them all to Drancy. Initially, the Germans forgot about the 17 children staying in the nursery on rue Édouard-Nortier, so early in the morning on July 23, the UGIF quickly sent them all elsewhere. On July 24, acting on the orders of Alois Brunner, Colonel Edmond Kahn, who the manager of the UGIF center on rue Lamarck and also inspector of all the UGIF homes in the Paris area, gave orders for the children to be brought back to rue Edouard-Nortier. They were arrested and dawn on July 25 and taken to Drancy.

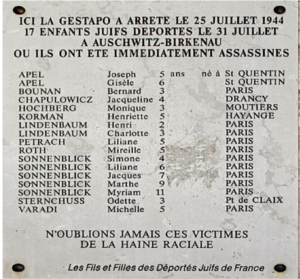

On July 31, 1944, Convoy 77, the last major transport from Drancy, set off for Auschwitz. On board were more than 300 children, including Gisèle and Joseph Apel. When the train arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, on August 3, 1944, the children were sent straight to the gas chambers, where they were murdered.

These memories of the two children are kept alive through the Saint-Quentin memorial and a plaque at the place where they were arrested at 67 Rue Edouard Nortier, in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

The memorial to the 17 children who were arrested at

67, rue Edouard Nortier in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

Notes & refreneces

[1] List of people to be arrested in the first roundup in Picardy, in July 1942

[2] Michèle d’Alméida-Zolty’s testimony, October 2023

[3] Ibidem

[4] Icek Goldring’s report from September 1945, entitled “Les juifs à Saint-Quentin”, (The Jews in Saint-Quentin) CMXXV/10/2/1: report from the Saint-Quentin UJRE section (Sept. 1945), Shoah Memorial.

[5] List of Jews in the Aisne department compiled by the German authorities after the 1940-1941 census (p.1), Aisne departmental archives.

[6] Anti-Jewish legislation: French official gazette, instructions to the sub-prefectures (1940-1942), ref. SC 11250: Aisne departmental archives

[7] List of foreign Jews to be arrested in the Saint-Quentin district, ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[8] Report by Captain Ouvrard, Chief of the Saint-Quentin military police on the arrest of foreign Jews (July 19, 1942), ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[9] Ibidem

[10] SIPO SD instruction to the regional prefect on the arrest of foreign Jews, ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[11] Report by Captain Ouvrard, Chief of the Saint-Quentin military police on the arrest of foreign Jews (July 19, 1942), ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[12] Michel Glicensztajn’s testimony, October 2023.

[13] Michèle d’Alméida-Zolty’s testimony, October 2023.

[14] List of Jews to be evacuated from Saint-Quentin, October 8, 1942, ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[15] Prefect’s instruction on the procedures to be followed during the roundup of October 8-9, 1942, ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[16] Ibidem

[17] Ibidem

[18] List of Jews arrested in Saint-Quentin, October 18, 1942, ref. 984 W 139, Aisne departmental archives.

[19] Individual Drancy interment records, October 16, 1942, Shoah Memorial archives.

[20] Drancy file on children, individual Drancy interment records for Léon and Simon Apel, October 16, 1942, Shoah Memorial archives.

[21] Drancy file on children, individual Drancy interment records, Shoah Memorial archives, French National Archives.

[22] Correspondence dated November 23, 1942, between Léo Israelowicz of the UGIF, (northern zone), and Mr. J. François, director of administrative affairs at the Paris police headquarters, about requests for the release of prisoners interned in Drancy, CDXXIV-44, Shoah Memorial archives

[23] https://convoi77.org/liste-des-deportes-du-convoi-77 /, and the individual Shoah Memorial page available on the Klarsfeld foundation website.

Français

Français Polski

Polski