Joseph WACHSPRESS

A Jew, a Communist and a Resistance fighter

Following in Joseph Wachspress’s footsteps

In a year when France is paying tribute to the Francs-Tireurs et partisans-Main d’Oeuvre immigrée (the “immigrant movement” of the armed section of the French Resistance – FTP-MOI) and the stories of Missak and Mélinée Manouchian and their Resistance group have been in the news, we decided, as part of a project carried out in partnership with the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, to pay our own tribute to a Polish immigrant Resistance member who fought for freedom and against deportation.

Who will remember him? Who will pay tribute to him if no one knows he even existed? He took part in the campaign against the German occupiers, plaguing them during numerous operations, as dangerous as they were heroic. We therefore feel that it is our duty to remember him and to share his life story with you.

With this in mind, we wanted to explore all possible lines of enquiry in order to retrace the life of Joseph Wachspress, a Polish immigrant who joined the ranks of the FTP-MOI, alongside Marcel Langer, in Toulouse in late 1942.

We decided to begin our research by splitting up into groups so that each could focus on a different chapter of his life.

The first problem we came across was that his name was almost always spelled incorrectly (Waschpress / Wachpress / Waschpresse), which made the search more complicated at first. Secondly, unlike some of his contemporaries, he gave no easily accessible testimonial, making it even more difficult to reconstruct his life both as a member of the Resistance and as a deportee.

Lastly, there may have been some confusion surrounding the history of his group (the 35th Brigade), because two of their leaders used the same pseudonym, “Commandant Robert”.

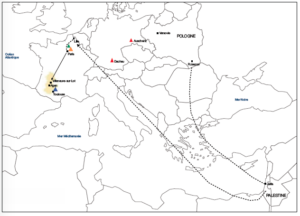

Joseph Wachspress was a man of few words, an unsung hero, and was still in the camps when France was liberated, so we had to find other ways to find out about his achievements. His story took us from Poland to Palestine, to various archive departments in the Occitanie region of France, to Paris, and even to Germany. We set out to work like real historians, cross-checking the information we had and contacting archive specialists and relatives of people who may have known him. And, more importantly, we found that some operations had been attributed to him even though the information given was not based on reliable, verifiable sources.

Isabelle Neuschwander, the former head of the French National Archives, kindly came to our school to meet us and helped to point us in the right direction. We gained a better understanding of the complexity of regional resistance movements during a visit to the Resistance and Deportation Museum in Toulouse. The French committee of Yad Vashem responded to our requests and was able to give us some information that was not yet available elsewhere.

We referred to a few pages in Jean-Yves Boursier’s book, based on a conversation the two men had in 1989 (where are the recordings?); and we drew on a short article by Joseph Wachspress himself, written in 1975, but not yet referenced elsewhere.

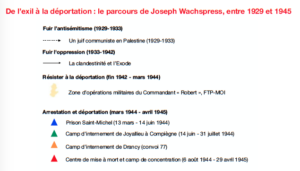

We based our research mainly on the records that Joseph Wachspress compiled in order to have himself recognized as having been deported as a Resistance fighter, and to be awarded the French Resistance medal. We have tried to go beyond the rather dull official records by illustrating his story with a few photos, his family tree, a map, and by giving his story more context by viewing it in the light of the eventful history of the 35th Brigade.

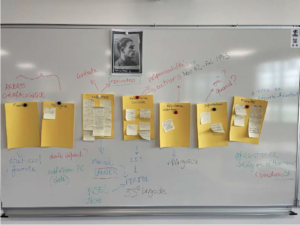

Our research board

We hope that this short account will prompt historians to look more closely at the history of one of the founding members of the 35th Brigade, or at least to address any inaccuracies on certain websites.

There are no doubt various reasons for this:

- In 1943, he continued to help out and to participate in attacks together with another FTP group based between the Lot-et-Garonne and the Dordogne departments, in which he was a Polish member of a mainly Italian group.

- Clearly, he did not wish to pass on this part of his story outside his inner circle of friends. Perhaps he preferred to stay out of the limelight given that his friends, Marcel Langer and Jacob Insel, both met a tragic end.

To address this forgotten chapter of his life – and he deserves to be listed in Le Maitron! [a French biographical dictionary website] – and to answer some of our questions, we would like to suggest some avenues of research to ensure that his legacy does not fade with time.

SOURCES

French Defense Historical Service

- Vincennes

GR 16P 599998 French Resistance Bureau file in the name of Joseph Wachspress - Online on the French website Mémoires des hommes

GR 19P 31-24 35e Brigade Marcel Langer et 3402e Compagnie

GR 19P 47-19 35e Brigade MOI / bataillon indomptable (Lot-et-Garonne) - Caen

AC 21P 690 366 Deported Resistance fighter file in the name of Joseph Wachspress

Shoah Memorial

- Paris

CMXXV-12-2 File on Joseph Wachspress

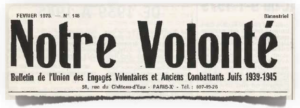

Notre Volonté magazine, 1975 (digitized version online)

The French committee for Yad Vashem

- File on Lucienne Deguilhem (very scant information on Wladimir and Yael Wachspress)

The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute

- Joseph Wachspress’s birth certificate

The French official legal website, Légifrance

- Journal Officiel (the French official Gazette)

- Decree dated May 31, 1947, published in the Journal Officiel on June 5, 1947

- Decree dated February 25, 1966, published in the Journal Officiel on March 2, 1966

- Decree dated April 12, 1984, published in the Journal Officiel on April 15, 1984

Claire Podetti, a member of the “Convoy 77” project team, and Elerika Leroy of the Resistance and Deportation Museum in Toulouse, were kind enough to scan some of the records.

Bibliography

Marcot, François, Dictionnaire histoire que de la Résistance, Robert Laffont, 2006.

The FTP-MOI members

- Manessis, Dimitri et Vigreux Jean, Avec tous des frères étrangers. De la MOE aux

FTP-MOI, Libertalia, 2024. - Wieworka, Annette, Ils étaient juifs, résistants, communistes, Perrin, 2018.

The Resistance in Toulouse

- Goubet Michel, La Résistance dans le Midi toulousain, Privat, 2015.

- Goubet Michel, La résistance étrangère à Toulouse (1940-1944), Bulletin de

l’Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent, Supplément n°8, 1995, p. 71-81. - Goubet Michel and Paul Dzbauges, Histoire de la Résistance en Haute-Garonne,

Milan, 1986.

The FTP-MOI 35th Brigade members

- Brafman, Marc, Les origines, les motivations, l’action et les destins des combattants juifs (parmi d’autres immigrés) de la 35e brigade FTP-MOI de Marcel Langer, Toulouse 1942-1944, Le Monde juif, n° 152, December 1994, p. 79-95.

- Boursier, Jean-Yves, La guerre de partisans dans le Sud-Ouest de la France, 1942-1944. La 35e brigade FTP-MOI, L’Harmattan, 1992.

- Lamazères, Greg, Marcel Langer, une vie de combats. 1903-1943. Juif, communiste, résistant… et guillotiné, Privat, 2003.

- Verbizier, Gérard de, Ni travail, ni famille, ni patrie. Journal d’une brigade F.T.P.-

M.O.I., Toulouse, 1942-1944, éd. Calmann-Lévy, 1994. - 35e brigade / Marcel Langer, France-tireurs et partisans de la main d’œuvre

immigrée, Toulouse 1940-1944, published by l’Amicale de la 35e brigade, 1983,

republished in 1944.

FTP-MOI 35th Brigade members testimonies

- Claude Lévy, Les parias de la résistance, éd. Calmann-Lévy, 1970.

- Damira Titonel-Asperti, Carmela Maltone, Écrire pour les autres – Mémoires d’une résistante – Les antifascistes italiens en Lot-et-Garonne sous l’occupation,

Bordeaux University press, 1999.

Joseph Wachspress

- Joseph Wachspress, Mon combat dans la 35e Brigade des F.T.P.F ,

Notre Volonté, February 1975.

French Resistance foundation website

Wachspress family member personal website(article published online in 2019)

“There will soon be no one left,” Marie Vaislic, a concentration camp survivor, said to her peers [1].

In some cases, there is already no one left. As the years go by, “the era of witnesses” (Annette Wievorka) fades away, and with it their memories.

In 1989, Jean-Yves Boursier interviewed Joseph Wachspress to help him write a book about the 35th Brigade. The veteran Resistance fighter was 80 years old. Although he was one of the founding members of this Toulouse Resistance movement, the book includes only three pages about him.

In 1993, Mosco Levi Boucault made a film about the Toulouse FTP-MOI group. Many of its members died during the Second World War, deported, shot or executed by guillotine. The survivors, who were already getting on in years, gave witness accounts, but not Joseph Wachspress, who was only mentioned twice. These former partisans joined the FTP-MOI group after Marcel Langer died, and our Resistance fighter was no longer in the Toulouse FTP group when they were recruiting for their intelligence operations and sabotage activities.

Joseph Wachspress died in 1996. How could we delve deeper into the life of this man whose story has become diluted within that of the group as a whole, and whose activities were sometimes carried out anonymously or in secret?

A long and patient search through the archives ensued, although the records were not as detailed as we would have wished. We also had to contend with some rather dull and repetitive official documents. We did not look at archives relating to repression, as the volume of documents involved was too great given the time constraints of the project.

We have therefore sought to put his life story into context, cross-referencing information in order to help identify the operations that he may have been participated in, and thus better understand how his activities contributed to the fight against deportation, both as a Jew and, above all, as a member of the Resistance.

The Wachspress family – Polish Jews

Joseph’s family history remains rather elusive, and the documentation we’ve found so far is rather dry: civil status records, mostly excerpts from the family record book. We gleaned a few details from the Internet, including that some cousins emigrated to the United States, and their descendants still live there: when and under what circumstances did they leave? What became of Joseph’s parents? For the moment, these questions remain unanswered.

Galicia, where the Wachspress originally came from, has been home to Jews since the 15th century. They hailed from Rzeszow, in the south of the region, also known as the “Jerusalem of Galicia”. In 1910, the Jewish population there was estimated at over 8,000, accounting for more than a third of the city’s total population.

Photo 1: A street in Rzeszów, 1915 postcard

Photo 2: The Jewish cemetery in Rzeszów in 2003. Photo taken by Marc Sagnol, ©mahJ

In the aftermath of the First World War, the Galician Jewish community became a casualty of the Polish-Ukrainian conflict, and a number of pogroms took place there. That may have been when some or all of the family decided to leave.

According to Joseph’s conversation with Jean-Yves Boursier on October 30,1989[2], he was active in a Jewish scouting organization, “Hashomer Hatzair”. It was through this left-wing Zionist youth movement that the British authorities, acting under the Mandate for Palestine, granted him an immigration permit for Palestine.

This enabled him to escape anti-Semitic persecution and join a communal farm near Tel Aviv in 1929. There he met some other Polish Jews, including Jacob Insel and Mendel Langer, who went on to found the 35th Brigade in Toulouse, and his wife, Yael, who had emigrated from Ukraine. Already committed to communism, they joined the Palestinian Communist Party (PKP). In the turbulent days of Arab and Jewish communism, they were arrested for taking part in the anti-colonial struggle against the British. Joseph was imprisoned in Jaffa and Yael in Bethlehem. When he was released, in 1933, he fled Palestine and travelled via Egypt to France.

We only know about this period of Joseph’s life through his testimony. In common with many other Jews who had migrated from Eastern Europe, he settled into kibbutz life. However, as an activist in the PKP, which stood for solidarity across class, ethnic and religious divides, he may have encountered some internal divisions stemming from the growing nationalist tension between the Jewish and Arab communities. But overall, it was his political activism, which was perceived as subversive, that forced him to leave the country as soon as he could.

There are no doubt some records of his time in British jails, for which it would be necessary to search the British National Archives, in which there is a vast collection of documents relating to the period of the British Mandate for Palestine, including civil and military administrative documents.

Joseph Wachspress, a communist immigrant

When he arrived in France in 1933, he stayed for a short while with his brother, Marcel, in Lille, in the north of France, and then worked at odd jobs in Paris. Although he had no official paperwork for the first two years, he was active in the “Jewish section” of the Communist Party and in the Jewish cross-union committee of the CGTU (Confédération Générale du Travail Unitaire or United General Confederation of Labor). By 1936, he was already regarded as a senior figure in the communist movement, and unlike Jacob Insel, he was not sent to Spain to fight in the International Brigade.

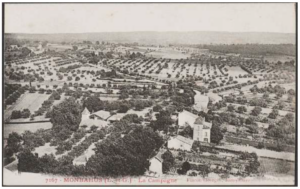

Following the signing of the German-Soviet Pact, the Communist Party and its affiliated organizations were dissolved on September 26, 1939, at which point the MOI and its Jewish section went underground. Although we have no details, we know that Joseph and his wife, who was pregnant at the time, fled at the time of the Exodus, eventually ending up in Villeneuve-sur-Lot, in the Lot-et-Garonne department, which was then in the Free Zone, in the southern half of France. His son Wladimir’s birth was registered there on October 10, 1940. According to his interview, Joseph worked at a farm school run by the ORT (Organisation Reconstruction Travail or Organisation for Rehabilitation through Training), which provided assistance to Jews in need, and some of whose staff were Communists. There were three ORT centers in the Lot and Garonne department. He most likely worked at the Angiroux center, near Monbahus. Lucienne Deguilhem, who lived on a farm in the village, took his son and his wife and kept them hidden.

The countryside near Monbahus.

Lot-et-Garonne departmental archives, ref. 7Fi 174/7

It was not, therefore, the enactment of the first decree on the “Status of the Jews” in October 1940 that prompted the couple to leave, but rather their political activities. Their previous experience of living underground enabled them to avoid being arrested. It no doubt also helped them to avoid registering themselves during the census of Jews, which was required by law on June 2, 1941.

When the Germans invaded the Free Zone in November 1942, Joseph, a seasoned Communist manager, made the transition from the class struggle to armed combat by enlisting in the FTP-MOI.

Resisting deportation: “Commandant Robert”

As a communist activist, Joseph Wachspress already had extensive experience of clandestine activities. According to the statements he submitted when he applied for the status of Interned and Deported Resistance fighter, and his interview in October 1989, he was one of the 35th Brigade’s very first members. At the end of 1942, when he came into contact with the MOI’s political leadership, he was chosen to join the “partisans”.

The core members of the 35th FTP-MOI Brigade in Toulouse were highly cosmopolitan. Already experienced in clandestine activism, armed combat in Spain and urban guerrilla warfare in Palestine, these staunch anti-fascists, Jews from Polish, Romanian and Hungarian backgrounds or Spanish Republicans were: Mendel Langer, Jacob Insel, Joseph Wachspress, Abraham Mittelman, Zeff Gottesman, José Linares-Diaz, Wladislaw Hamerlak, Stefan Barsony, Luis Fernandez, Sevek Michalak and Rachel Perelman.

This small international group, formed at the behest of the Communist Party, turned to armed rebellion as a means of combating and evading repression and persecution. Joseph Wachspress’s pseudonym in the 35th Brigade was “Commandant Robert”. His military duties included leading the C.O.R. (Commission aux Opérations de la Résistance, National Council of the Resistance).

The Toulouse FTP-MOI’s various types of operations had several objectives:

- sabotage railroad lines in order to disrupt the Wehrmacht’s food and ammunition supplies.

- strike German soldiers, Militia leaders and anyone else who helped them to catch and deport Jews.

Most of the 35th Brigade’s military operations took place in Toulouse, Agen and Montauban, supported by an intelligence service staffed mainly by women. When the brigade was first set up, the leaders themselves took part in the operations. It is often difficult to pinpoint what exactly one individual did within the group’s operations as a whole.

Based on eyewitness accounts and historical records, a number of operations that Commandant Robert led can now be reliably identified. While he was sometimes involved in sabotage operations at railroad stations or on the tracks, he was primarily involved in attacking and executing German officers and officials.

A 7,65mm caliber semi-automatic pistol.

French National Resistance Museum/Henri Jablon collection, (Inv. 2006).

Threre were not enough weapons for the whole brigade to have one each, so they had to hand them in at the end of each operation, and collect them for the next one.

Commandant Robert was no stranger to violence. We have very little information about how he was injured, apart from the wounds he sustained during one operation in particulier:

- The first operation took place in March 1943, with his friend Jacob Insel and Sewer Michalak, alias “Charles”, the Brigade’s chief technician and bomb-maker. After scouting the area in advance, Wachspress volunteered to plant two explosive devices in the L’Ours Blanc hotel-restaurant in Toulouse, where the German army was based. The first bomb was intended to bring a number of men together, while the second was to be detonated a minute or two later to cause as much damage as possible.

- On June 13, 1943, using the same technique, he and two other FTP-MOI members set off bombs in front of the German Military Police headquarters in Toulouse. Several Nazi officers were killed, including Major von Speicher, the deputy head of the Toulouse Gestapo, and two other officers were wounded. In the wake of this operation, the Kommandatur ordered a curfew.

- A few days later, on June 17, 1943, he was assigned to execute a Gestapo agent. According to his testimony, he arrived at the target’s home disguised as a telegrapher and delivered the “sentence and execution on the spot”[3]. However, a bodyguard returned fire and he was shot several times in the leg. He managed to escape and eventually got some medical attention. “Robert” spent his convalescence at “Charles place”, hidden above the weapons storage area.

After that, as he was wanted for “terrorist activities”[4], the FTP leadership transferred Joseph Wachspress to the Dordogne department, where he was put in charge of the Lot-et-Garonne, Gers and Dordogne departments in July or August 1943 (the date varies according to sources). In theory, therefore, he was no longer in Toulouse when Marcel Langer was executed by guillotine in the Saint-Michel prison on July 23, 1943.

He continued his sabotage activities, mainly targeting railroads, and launched attacks on Gestapo and Militia leaders. He reorganized the FTP “Indomitable Battalion” by recruiting young militants as back up and reserve fighters for the Brigade[6]. In July 1943, the detachment numbered barely 80 men and women, the majority of whom were Italian migrants.

The best-documented example is that of Damira Totinel (1923-2011), who came from an Italian family that had fled fascism, and who recounts in her memoirs how Commandant Robert recruited her Having overheard discussions between the FTP-MOI leader and her father, she asked Commandant Robert if she could join the Brigade. She began by transporting covert documents and weapons for guerrilla operations. In the spring of 1944, she was arrested at the Matabiau station in Toulouse. She was detained, tortured and held for five months, but refused to talk. On July 24, 1944, she was deported to the Ravensbrück camp, from which she was liberated on May 3, 1945.

While continuing to organize rural operations, such as burning wheat sheaves to prevent them from being delivered to the Germans, Commandant Robert continued the armed struggle against the Nazis in the Dordogne, sometimes with the help of Enzo Lorenzi, alias “Robert”[7] and Axel Simondy, alias “François”:

- In October 1943, on either the 9th or 17th, he ordered the Gestapo headquarters in Périgueux to be blown up. Two bombs exploded one after the other, killing many people. Lorenzi intervened to prevent the group from being arrested.

- After the war, Joseph Wachspress himself described one of the most spectacular operations as follows: “Under my command, the Gestapo agent Conrad, from Sainte-Livrade (Lot-et-Garonne), who had been tracked down by our special service, was executed. The execution took place on a Sunday morning in the local café. The café was full of people (there were even some French military policemen present) and the comrade who was to carry out the execution did not know the traitor. He walked up to the owner and told him he had a message to deliver to this gentleman. The owner pointed out the individual. With no hesitation, having double checked that his backup was in position, our comrade handed the traitor his sentence, carried out his mission there and then and headed out the door without anyone interfering”[8].

The documentation that some of the group leaders produced after the Liberation, in order to have their groups recognized as fighting units, is much more concise, but nevertheless enabled us to piece together the chronology of their operations. The attack on Sainte-Livrade is well documented and dated “12/43”. In addition, Joseph Wachspress’s account is in keeping with the tactics that other FTP-MOI units, such as Manouchian’s group, adopted.

By choosing to engage in armed combat as a means of opposing deportation, and as attacks on Gestapo officers and militiamen gathered pace, Commandant Robert was increasingly vulnerable to reprisals. Wanted by occupying forces, on March 12, 1944, he was arrested in Agen while carrying a gun.

Joseph Wachspress, a “political deportee”

The following day, Joseph was transferred to the Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse, where he was tortured horribly and “in danger of losing his sight as a result of this abuse, despite which he remained absolutely silent so as not to compromise his comrades and his organization”[9].

During the Occupation, the Saint-Michel prison was the main holding center for Resistance fighters[10]. The Gestapo used three wings of the prison, cramming in hundreds of men and women arrested for resistance activities. German soldiers guarded the area. From the summer of 1944 onwards, resistance fighters were only held in Saint-Michel for a few weeks and were then either executed or deported.

Joseph was interned on March 13 and transferred to the German police detention camp at Royallieu, near Compiègne, on June 14, 1944. As the camp archives are not available, we do not know whether he was interned in the political section or the Jewish section of the camp. Either way, he was transferred to Drancy and was on the Convoy 77 deportation list on July 31, 1944.

The Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse

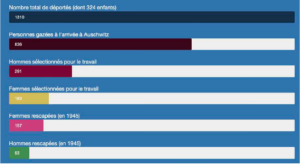

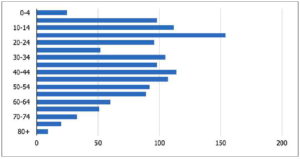

Through the work of German historian Volker Mall and the Convoy 77 organization, the story of the last major transport of deportees from Drancy is much better known. On July 31, 1944, 324 children and 986 men and women, including 35-year-old Joseph Wachspress, were deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp.

In Alexandre Doulut, Serge Klarsfeld and Sandrine Labeau’s “Mémorial des 3943 rescapés juifs de France” – Le temps des rafles catalogue de l’exposition (Memorial to the 3943 Jewish survivors from France – The Days of the Roundups), published in March 1992, p.90-91, Joseph Wachspress is only quoted once about his time in the camps: “l’enfer des camps concentration” (“the hell of the concentration camps”).

From his deportee number (B-2933), it appears that we can trace his journey from when he arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, in occupied Poland, on August 3, 1944, to when the Americans liberated the Dachau camp in Germany on April 29, 1945. As soon as Convoy 77 arrived in Auschwitz, 836 deportees were sent straight to the gas chambers, while the rest, 183 women and 291 men, were selected to go into the camp to work. On October 16, 1944, at least 75 men, with prisoner numbers B-3675 to B-3955, were transferred to the Stutthof concentration camp near Danzig. For the time being, it is not known whether Joseph Wachspress was one of them.

Alternatively, he may have been transferred to the Vaihingen-surl’Enz camp near Stuttgart in February 1945, then evacuated to Dachau in April. In fact, in the records in his deportation file, he never mentioned Auschwitz, just Dachau. In his 1989 testimony, he said that he was one of the many deportees who was sent on death marches, and that he “gave his all to save several deportees”. In addition, the submission[11] in his application for the French Resistance Medal supports his story, mentioning that as “a deportee to Dachau, he again distinguished himself by his exemplary conduct”[12], but that does not really tell us anything more.

Only four prisoners from Convoy 77 were still alive in the Dachau camp when it was liberated on April 29, 1945.

Survivors in Dachau after the camp was liberated.

Photo from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum

Joseph Wachspress, a deported Resistance fighter and medal holder

Joseph Waschpress was first recognized for his commitment to resisting the occupying forces by attacking the men responsible for deporting Jews and Resistance fighters, and for “fighting for freedom, against war, fascism and oppression”[13], when he was granted French citizenship in 1946. His services in the Resistance services were acknowledged once again when he was awarded the French Resistance Medal on March 31, 1947[14].

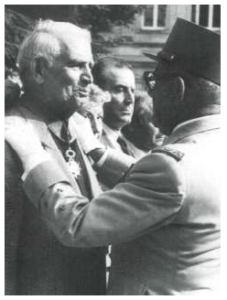

His military achievements were rewarded on February 17, 1948, when he was awarded the French War Cross with a commendation in the French Order of the Army[15].

Lastly, he was made a Knight of the French Legion of Honor on May 31, 1947 “for exceptional service in war”, was made an Officer on February 25, 1966, and then a Commander on April 14, 1984[16].

Photo 1: French Resistance Medal

Photo 2: French War Cross, Croix de Guerre, with Order of the Army commendation

Photo 3: Robert Wachspress being presented with the Commander of the Legion of Honor necktie (in Agen, in 1985)

On the other hand, he was only awarded the status of deported resistance fighter on awarded on April 6, 1955, and not without difficulty! The FTP leadership did not always provide a detailed history of their units. This was true of the 35th brigade, and for good reason: many of them had died in combat or in the camps, or had been executed by the Germans. As a result, after starting his application in December 1953, Joseph Wachspress received a letter from the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs, dated February 15, 1954, asking him to “produce a certificate from Mr. Jean Fouquet, leader of the FTPF in Haute Garonne, the FFI unit of which you were a member, specifying the reason for your arrest”[17].

Over the course of this story, two people fade into the background as far as the records go: his wife and his son. As a result of some family history research, we were able to establish that Lucienne Deguilhem (1898-1980), a town hall secretary who lived on a farm in the Lot-et-Garonne department, saved his son.

By contacting her daughter and then the French committee for Yad Vashem, we discovered that she had been named “Righteous Among the Nations” posthumously in 2013. She had hidden over twenty Jews, including thirteen children including Vladimir and also Joseph’s wife Yaël[18].

A Jewish immigrant, he fought against xenophobia and anti-Semitism in order to prevent his loved ones from being deported, but overall, it was his political activism and work in the Resistance that encompassed all the really consequential aspects of his life’s work.

Through this research, which must be continued, we have brought Joseph, together with Yael, into our own individual Pantheon [a monument in Paris in which the great men and women of France are laid to rest. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panthéon].

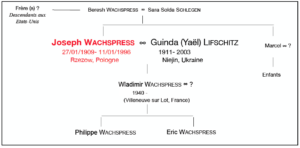

Joseph Wachspress family tree

Compiled from the civil status records in Joseph Wachspress’s deported resistance fighter application, his death notice published in the Le Monde newspaper on January 16, 1996, p. 1, and a web page written by one of Joseph’s cousins’ sons, in English, published on May 3, 2019.

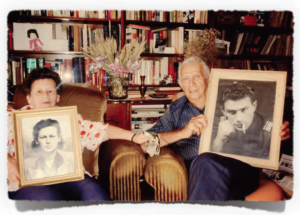

Joseph and Yael Wachspress in 1993.

Photo taken from the Ashtoveen website here

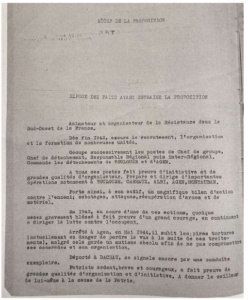

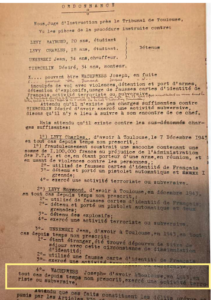

Documents below

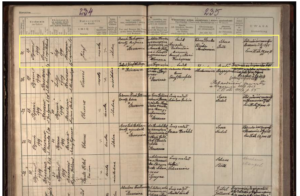

- Joseph Wachspress’s birth certificate

- FFI confirmation of membership certificate

- Submission for the French Resistance fighter medal

- Chronological summary of the 35th Brigade operations (extract)

- Legal proceedings against Claude and Raymond Levy and Jacob Insel, in which Joseph Wachspress is mentioned (December 1943)

- Joseph Wachspress’s testimony (1975)

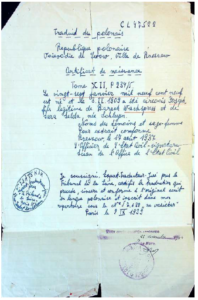

Joseph Wachspress’s birth certificate. Source: Polish State archives at Rzeszów. Scanned by The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute

Translation of the birth certificate in the Resistance office file on Joseph Wachspress

(French Defense Historical Service, ref. GR 16P 599998)

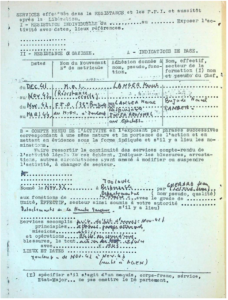

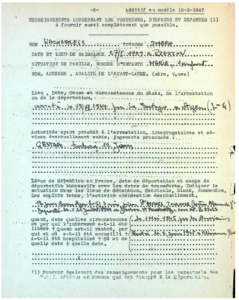

FFI confirmation of membership file

(French Defense Historical Service, ref. GR 16P 599998)

FFI confirmation of membership file

(French Defense Historical Service, ref. GR 16P 599998)

FFI confirmation of membership file

(French Defense Historical Service, ref. GR 16P 599998)

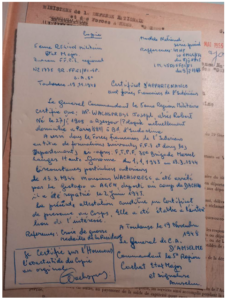

Submission for the French Resistance fighter medal

Order of Liberation file

Chronological summary of the 35th Brigade operations (extract)

(French Defense Historical Service, ref. GR 19P 31-24

Legal proceedings against Claude and Raymond Levy and Jacob Insel, in which Joseph Wachspress is mentioned (December 1943)

Haute-Garonne departmental archives, ref. 5795W 610/616

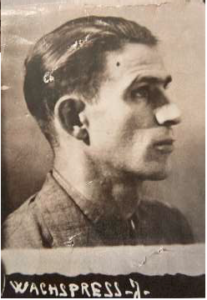

Photo of Joseph Wachspress, found in the Levy brothers’ belongings at the time of their arrest: might this have been used to make false papers?

Joseph Wachspress’s testimony

Notre Volonté, February 1975

(Shoah Memorial, UEVACJEA collection)

Sources

- [1] Marie Vaislic with Marion Cocquet, Il n’y aura bientôt plus personne, Grasset, 2024.

- [2] Jean-Yves Boursier, La guerre de partisans dans le Sud-Ouest de la France, 1942-1944. La 35e brigade FTP-MOI, éd. L’Harmattan, 1992, p.68-70.

- [3] Joseph Wachspress, Mon combat dans la 35e Brigade des F.T.P.F, Revue Notre Volonté, February 1975.

- [4] Haute-Garonne departmental archives, ref. 5795W 610/616, December 1943.

- [5] French Defense Historical service, ref. 19P 47/19 35th FTP-MOI brigade.

- [6] Damira Titonel-Asperti, Carmela Maltone, Écrire pour les autres – Mémoires d’une résistante – Les antifascistes italiens en Lot-et-Garonne sous l’occupation, Bordeaux University press, 1999, p. 41.

- [7] Both men used the same pseudonym, so it can be hard to tell who was behind a specific operation.

- [8] Joseph Wachspress, Mon combat dans la 35e Brigade des F.T.P.F, Notre Volonté, February 1975.

- [9] Museum of the Order of the Liberation, Wachspress file, proposal for the Resistance medal.

- [10] La prison Saint-Michel, un lieu de mémoire au coeur de Toulouse, Haute-Garonne General Council, January 2008.

- [11] Boursier, Idem, p.71.

- [12] Museum of the Order of the Liberation, Wachspress file, submission for the Resistance medal.

- [13] The last sentence of Joseph Wachspress’s article.

- [14] French Official Gazette, decree dated March 31, 1947.

- [15] French Official Gazette, decree dated February 17, 1948.

- [16] French Official Gazette, decrees dated May 31, 1947, February 25, 1966 and April 14, 1984.

- [17] French Defense Historical service, ref 21P 690 366

- [18] https://yadvashem-france.org/dossier/nom/12532/

Français

Français Polski

Polski