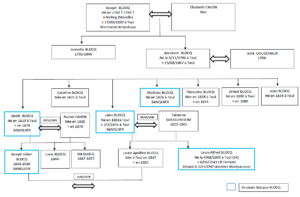

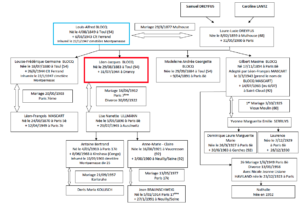

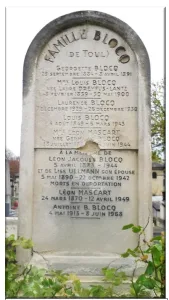

Léon Jacques BLOCQ

Léon Jacques Blocq was born on August 29, 1883 in Toul, in the Meurthe et Moselle department of France. He was born into a middle-class family whose grandfather, Joseph Blocq, had migrated from Nelling, also in Moselle, to Toul in the 1790s. He was the second of four siblings:

- Louise Frédérique Germaine (who went by the name of Germaine), the eldest child, who was born on July 18, 1880 in Toul.

- Madeleine, Andrée, Georgette, who was born just over a year after Léon, on September 29, 1884 in Toul, and died in Paris in 1891.

- Gilbert Maxime (who went by the name of Maxime), the youngest of the family, who was born on November 17, 1894 in Paris.

Léon-Jacques’ parents

Léon’s parents, Louis-Alfred Blocq and Laure Lucie Dreyfus, were married in Mulhouse in 1877. They lived in Toul before moving to Paris around 1890. Laure died in Paris in 1900, when her youngest child, Gilbert Maxime, was just 5 ½ years old. From then on, his older sister, Germaine, raised him.

Louis-Alfred, who joined an army unit called the “Garde Mobile” in Toul in 1870, took part in the siege of the town during the war against Prussia. The Germans hoped to take over the railway line between Nancy and Paris, but they had not expected the citadel of Toul to resist them so vigorously! It was only after they deployed 15,000 men and fought for several days, raining shells down on the town, that the Prussians succeeded in taking the citadel. The Germans took more than 2,300 French soldiers prisoner, and captured the fortress’s equipment, including 71 heavy weapons that would later be used to attack Paris.

The memorial to those who died during the siege of Toul

The memorial to those who died during the siege of Toul

Louis-Alfred was second lieutenant in the reserve artillery and then in the territorial artillery from 1876 to 1889. He was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor on January 12, 1909, and an Officer of the Legion of Honor in 1933.

Louis-Alfred Blocq was also a man very much involved in civilian society. From 1871 onwards, he played an active role in relief work for the people of Alsace and Lorraine. In 1889, he founded the Cercle toulois de la ligue de l’enseignement (the Toul circle of the French educational league.). Jean Macé had founded this public education movement in 1886. Its aim was to “establish a public education service free from the control of the Catholic Church, secular in both subject matter and teaching staff, open to all, and guaranteed to be accessible to all by being compulsory and free of charge”.

He was appointed vice-president in 1904 and president in 1907 of the Foyer du soldat de Paris (Paris Soldiers’ Center). In keeping with Jean Macé’s well-known quote “Pour la patrie, par le Livre et par l’épée” (“For the fatherland, by the book and by the sword”), at the beginning of the 20th century, the Ligue pour l’enseignement set about founding soldiers’ centers intended “to ensure that military personnel far from their homeland, their relations, of their friendships, a real family home that preserves them from isolation, defends them against the temptations of idleness and provides them, in the hours of freedom left by the barracks, with a meeting place with healthy and educational distractions” (source: Le Littoral, January 2, 1902). Soldiers had access to a library, writing room, reading room, music room, games room, exercise room, etc. as well as conferences, courses, excursions and parties. Louis-Alfred was instrumental in setting up the regimental libraries in this center.

The Paris soldiers’ center in 1916

The Paris soldiers’ center in 1916

In its character assessment report on Louis-Alfred, conducted with a view to awarding him the Legion of Honor, the Ministry of War noted that Mr. Blocq “has shown the most intelligent and active devotion in the organization of the Soldiers’ center” and that he “has rendered the most remarkable services to the Ligue de l’enseignement.”

On the professional front, Louis-Alfred Blocq, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in literature and science and was a qualified lawyer, would seem to have initially practiced as a lawyer, and was also a foreign trade advisor. He was best known, however, as a banker.

The BLOCQ FRERES (Blocq brothers) bank, on Place Dauphine in Toul, was founded in 1862 by three brothers: Léon (Louis-Alfred’s father), Jacob and Mathieu.

In 1870, it became BLOCQ FRERES ET FILS (Blocq brothers and son) as Jacob’s son, Joseph-Julien, was appointed partner. Mr. Viller, a notary in Toul, registered the formation of “a general partnership to carry out banking, escrow and debt collection activities, food and fodder supply businesses, and the buying and selling of real estate”.

In 1874, new articles of association were signed at the same notary’s office, as Léon had died and his son Louis-Alfred joined the bank on May 15, 1874.

In 1877, Mr. Viller registered an amendment to the articles of association: from then on, any associate could resign from the partnership “at any time and without giving any reason”, which had not previously been the case. This change was implemented in 1894 when Mathieu left the company. In 1894, Louis-Alfred and his cousin Joseph-Julien ran the bank. The remaining partner, Jacob, appears to have left by this time. The bank’s head office remained in Toul, even after Louis-Alfred and other family members set up a branch at 9 rue Vaneau in Paris, as we shall see later on.

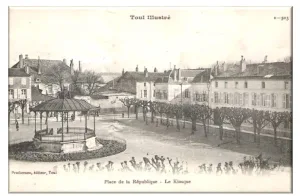

Place Dauphine in Toul, now renamed Place de la République and the site of the Blocq Brothers and Son bank.

Place Dauphine in Toul, now renamed Place de la République and the site of the Blocq Brothers and Son bank.

The Blocq Brothers and Son bank did not escape the controversy sparked by the Dreyfus Affair at the end of the 19th century. Indeed, the French newspaper L’Intransigeant, on December 10, 1897, implied that the funds of the Dreyfus syndicate were deposited at the Blocq bank, at 69 rue de Courcelles in Paris. The syndicate’s meetings were said to have been held there, and the paper said that “large sums of money had recently been deposited by Blocq via third parties on behalf of the syndicate”. The journalist also asked: “Is it true that the amount of money paid out on behalf of the syndicate to date amounts to seven million eight hundred thousand francs?”.

But what was this “syndicate” that the journalist was referring to? Emile Zola, convinced that there had been a miscarriage of justice, was deeply involved in the Dreyfus affair. In the December 1, 1897 issue of the French newspaper Le Figaro, he published an article entitled Le Syndicat, in which he condemned the slander of Jewish banks:

Columns from Le Figaro, December 1, 1897

In his article, Emile Zola went on to criticize the role of the press, which was predominantly anti-Dreyfus, along with the French army and the courts, and concluded with these words:

“About this syndicate, ah! yes, I’m in it and I hope all the good folk of France will be in it!”

On January 19, 1920, Mr. Poirot, a notary in Toul, registered further changes in the bank’s articles of association: a new partner joined Louis-Alfred Blocq and his cousin Joseph-Julien: Louis-Alfred’s son-in-law, Léon Mascart, Germaine’s husband.

In 1928, Joseph-Julien left the family bank and his shares were sold. Louis-Alfred and Léon Mascart were then the only two partners in the new company, Banque Blocq et Cie (Blocq and Co. bank) whose head office was still in Toul.

A few years later, the Second World War drove part of the family into exile in Clermont-Ferrand, in the Puy-de-Dôme department of France. Louis-Alfred, his daughter Germaine and his son-in-law Léon Mascart took refuge there. On October 21, 1940, the Commercial Court registered the temporary transfer of the bank’s head office to 15 rue Bonnabaud in Clermont-Ferrand. Then, on January 20, 1941, the same Court reported that Louis-Alfred was leaving the bank to become a limited partner. At the age of 91, he had been unable to run the business for some time, due to his poor health. As of January 1, 1941, the company had only one manager, Léon Mascart, and its name was changed to Mascart et Cie (Mascart and Co).

Léon-Jacques’ elder sister, Germaine

On May 20, 1903, Léon-Jacques’ elder sister, Germaine, married Léon-François Mascart, who was born in 1870. The couple do not appear to have had children of their own. They did, however, raise Germaine’s brother Maxime after his mother died. In fact, Léon François Mascart adopted Maxime by order of the Seine Civil Court on March 3, 1943. His surname thus became Maxime Blocq-Mascart.

Germaine, like her father, was heavily involved in charity work.

During the First World War, she was a staff nurse at the Auxiliary Hospital 111 in Maxéville in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France. The hospital was on the premises of the Meurthe-et-Moselle women’s teacher training college on rue de Nancy in Maxéville.

Auxiliary hospitals were temporary military hospitals set up following mobilization by organizations dedicated to helping the wounded. Those numbered 100 to 199 were run by the Union des Femmes de France (French Women’s Union). The hospital at Maxéville was a surgical unit with around two hundred beds.

The hospital manager was Ms. Evrard, the head nurse was Ms. Mascart, and the head physician was Dr. Louis Senlecq.

The buildings of the former teacher training college. Photograph by P. Labrude, 2017.

The buildings of the former teacher training college. Photograph by P. Labrude, 2017.

In early February 1915, a large number of wounded soldiers were brought to the hospital as a result of heavy fighting at Xon, north of Pont-à-Mousson: on February 2, for example, 150 were admitted. In all, until its closure at the end of the conflict, the hospital provided 122,785 days of inpatient care.

The most important aspect of the hospital’s work was caring for casualties, first in the emergency department, then following surgery, with particular emphasis on monitoring the effects of auto-extensor appliances fitted by the surgical team, cast removal, wound healing, post-operative re-education and the like. Of course, patients spent much of their time on the ward. However, the Chief Medical Officer and his staff did their utmost to limit the boredom by organizing shows, games and concerts for the patients.

In addition to his work as a surgeon, the head physician, Louis Senlecq, designed equipment to facilitate the evacuation of casualties from the battlefield, such as the suspended stretcher, which only needed two men to carry it, which made it easier to negotiate the bends in the trenches. He also developed appliances to improve wound healing, reduce ankylosis and speed up recovery, among other things.

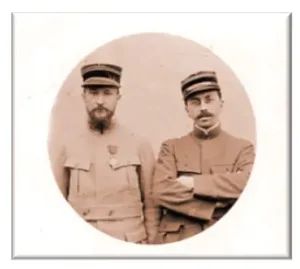

Medical officers 1st class, Louis Senlecq (right) and Maurice Lucien (left), in Nancy in March 1915. Photo from Dr. Senlecq’s family archives.

Medical officers 1st class, Louis Senlecq (right) and Maurice Lucien (left), in Nancy in March 1915. Photo from Dr. Senlecq’s family archives.

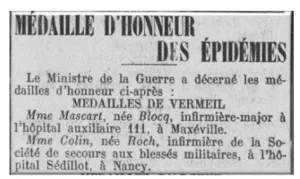

The 1919 issue of the Meurthe et Moselle Bulletin reported that the Minister of War had awarded Germaine Mascart the “Médaille Vermeil des Epidémies” (Vermeil Epidemic Medal). This medal was introduced in 1885 to honor “people who have shown particular devotion to duty during epidemics”. During the First World War (1914/1918), Germaine Mascart must have cared for the patients affected by the Spanish flu epidemic.

After the First World War, in 1922, Germaine Mascart helped set up the Youth Section of the French Red Cross. The organization was dedicated to providing first-aid courses, financing summer camps, helping seniors and collecting medicinal plants.

From 1931 to 1940, she was also deputy secretary of the federation of departmental educational organizations for wards of the state.

However, it was Germaine Mascart’s role as Secretary General of the Hygiène par l’Exemple (Hygiene by Example) nonprofit organization from the 1920s to the 1940s that was her greatest achievement. Her brother, Maxime Blocq-Mascart, was deputy treasurer during the same period.

Founded on February 27, 1920 at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, under the leadership of the manager, Dr. Roux, Hygiene by Example was instrumental in teaching the importance of hygiene in elementary school. This initiative was part of the ongoing battle against infant mortality, tuberculosis and other social issues such as alcoholism and venereal disease.

In practical terms, the organization installed showers, washbasins, lockers and changing rooms in schools. Each child had his or her own glass, toothbrush and towel, which were changed weekly. Next to the washbasins there was a changing room where each pupil had his or her own locker, in which there were slippers and a smock. When they arrived in school, the children left their outdoor clothes and shoes in the locker until they left the school at the end of the day.

In 1936, Jean Zay, the French Minister of Education, sent out a circular informing school inspectors and principals of teacher training colleges about plans for a course to train staff for vacation camps. An organization called “Centre d’Entraînement pour la Formation du Personnel des colonies de vacances et des Maisons de Campagne des écoliers” (Training Center for Staff of Vacation Camps and Schoolchildren’s Centers in the country) was founded. It was based in the Hygiene by Example headquarters.

In March 1939, Germaine Mascart began working on the project and also wanted rural schools to be prepared to take in children from urban areas if they had to be evacuated. In April 1940, she proposed setting up field centers in the countryside for evacuated children, to provide even more comprehensive educational facilities than schools. In 1940, the first six field centers were opened, four of which were in the occupied zone and two in the free zone. In 1942 and 1943, a further eight centers were added. In all, 40,000 vacation days were provided for malnourished children, most of whom were from Paris.

Germaine Mascart was the driving force behind the Hygiene by Example organization. Jean-Bernard Wojciechowski, a doctor of sociology, wrote in an article about the organization in which he said of Ms. Mascart “we might associate her work with traditions in which charity and solidarity were considered a duty”.

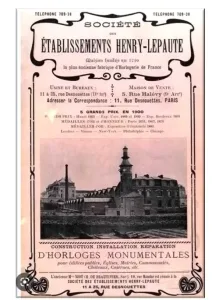

Germaine’s husband, Léon-François Mascart, was a former naval officer and Knight of the French Legion of Honor. When they were married in 1903, he was the manager of the Henri-Lepaute company at 6 rue Lafayette in Paris, which specialized in the manufacture of clocks and optical equipment for lighthouses. Augustin Henry Lepaute, who was born in 1800 and studied under Gustave Eiffel, was watchmaker to Louis-Philippe and Napoleon III. In 1823, he joined forces with Augustin Fresnel, head of the French lighthouse and beacons authority. They went on to supply equipment for over 1,300 lighthouses worldwide. When Henri Lepaute died, his sons Edouard-Léon and Paul-Joseph took over the firm.

Henry-Lepaute catalog, circa 1930. The factory in Paris had a lighthouse on the roof. Source: private archives.

The Henry-Lepaute clock at the Palais Bourbon in Paris

As mentioned above, Léon-François Massart was a partner in the Blocq & Co. bank, and in 1941 became the sole managing director.

His wife Germaine died on June 26, 1944 in Clermont-Ferrand, in the Puy-de-Dôme department of France, a year after his father-in-law, Louis-Alfred.

At the end of the war, Léon-François Mascart returned to Paris, where he died in 1949.

Prior to that, the bodies of his wife and father-in-law had been removed to the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris, where they were laid to rest on January 22, 1947.

Léon-Jacques’ younger brother, Maxime

Maxime Blocq was born in Paris on November 17, 1894. Having lost his mother at an early age, he was raised by his sister Germaine and then adopted by his uncle Léon Mascart in 1943. Mobilized at the start of the Great War, he served in various regiments ( the 10th Engineer Regiment, 13th Artillery Regiment and 27th Dragoon Regiment) before being assigned to the air force in March 1917, where he became a pilot in Squadron 231. After the war, Maxime Blocq-Mascart pursued his academic education at the prestigious Political Science Faculty in Paris.

Although he apparently trained as an architect, he joined the family bank, which had become Blocq & Co., where he acted as director and authorized signatory while Louis-Alfred Blocq, his father, and Léon-François Mascart, his brother-in-law, were partners and managers.

Maxime was also involved in a number of other companies and non-profit organizations. For example, he was a partner and joint managing director of “Mascart, Allez & Co“, a company that specialized in public construction work. He was also a director of the Committee for the Defense of Shareholders of the “Société Suédoise des Allumettes” (Swedish Match Company) and of the “Kreuger et Toll” company. He was director of the “Entraid’sociale“, a mutual social aid service, and delegate and treasurer of the non-profit organization “Les Compagnons des professions intellectuelles” (Intellectual Professions Guild). As previously mentioned, he was also Treasurer of the “Hygiene by Example” organization.

He was also an occasional contributor to the weekly paper “L’Europe nouvelle” (New Europe), which was edited by Ms. Louise Weisse. After France was liberated, he became founding president of “Le Parisien libéré” (“The Liberated Parisian”), which he ran until 1947…

In 1925, he joined the Confédération des travailleurs intellectuels (CTI, or Confederation of Intellectual Workers), of which he was vice-president shortly before the Second World War. However, Maxime Blocq-Mascart is best known for his role in the French Internal Resistance movement. In the summer of 1940, he refused to accept defeat. Back in Paris, he formed a resistance group with his friends from the CTI. In December 1940, this initial cell merged with that of Jacques Arthuys, to form the Organisation Civile et Militaire (OCM, or Civil and Military Organization) in which Maxime Blocq-Mascart, alias “Maxime”, “Baudin” or “Féry”, was in charge of the civilian office. He sought to develop a political program within the movement, and was involved in drafting constitutional and administrative reforms for the paper, Libération.

During 1943, he adopted a rather contradictory attitude to efforts to unify the Resistance movement. On March 26, 1943, he took part in the first meeting of the Northern Zone Coordination Committee. In May, he refused to take a seat on the Conseil national de la Résistance (CNR, or National Council of the Resistance), in order to underline the OCM’s opposition to the presence of political parties within it.

He remained critical of the organizations set up by Jean Moulin until the end of 1943. Nevertheless, he took part in CNR meetings, replacing Jacques-Henri Simon, and became vice-president in June 1944. As a member of the permanent steering committee of the CNR, he represented the three main movements in the northern zone (the OCM, the CDLL and the CDLR). Having gone underground in August 1943, Maxime Blocq-Mascart took over the leadership of the OCM when Alfred Touny was arrested in February 1944 and remained in charge until the Liberation.

This brief summary of Maxime Blocq Mascart’s life illustrates his wide-ranging achievements as a director of a variety of companies, his involvement with non-profit organizations, his trade union and intellectual activities, and his role in the French Resistance. He was awarded numerous honors: Knight of the Légion d’Honneur, Resistance Medal, Volunteer Fighter Cross of the Resistance, Second World War Cross 1939/1945 and Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor.

Portrait of Maxime Blocq-Mascart drawn on July 9, 1957.

French National Archives / Maxime Blocq-Mascart collection

As regards his personal life, Maxime Blocq Mascart married Yvonne Serruys in 1925. They had two daughters: Dominique, who was born in 1927, and Laurence, who was born in 1929 but died the following year. He married again in 1949, to Nicole Haviland. They had a daughter, Nathalie, in 1952, and were divorced in 1958.

Maxime’s second wife, Nicole Haviland, was descended from families whose prestigious names influenced the decorative arts sector in France, both in glass and porcelain. Her grandfather, René Lalique, was a jeweler and master glassmaker who influenced the Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods by using materials hitherto little appreciated in jewelry-making, such as horn, ivory, semi-precious stones, enamel and glass. Nowadays, some 250 men and women, including seven of the most skilled craftsmen in France, continue to pass on their expertise at the factory in Wingen-sur-Moder, in the Bas-Rhin department of France.

Nicole’s mother, Suzanne Lalique, became part of another artistic family through her marriage to Paul Burty Haviland. Her father-in-law was a renowned manufacturer of Limoges porcelain. For over 175 years, Maison Haviland has contributed to the best of French tradition, it’s porcelain gracing the finest tables in the world’s most prestigious hotels, including the Ritz in Paris, the Dorchester in London and the Shangri-La Hôtel in Paris.

Suzanne Lalique Haviland with her daughter Nicole in around 1925

Don Nicole Maritch-Haviland and Jack Haviland, 1993, Musée d’Orsay in Paris

The daughter of René Lalique and the wife of Paul Burty Haviland, Suzanne Haviland herself became a well-known designer who influenced her time and such famous institutions as the Manufacture de Sèvres and the Comédie Française. She worked with a wide variety of materials, from glass and porcelain to textiles, costumes and stage sets for theater and opera.

Some of Suzanne Lalique-Haviland’s work

Costume sketch for Polidas in Molière’s “Amphitryon” at the Comédie-Française in 1957.

Painting “La Garçonnière” or “Monsieur’s neckties, 1933

Léon-Jacques Blocq

Léon-Jacques and his family moved from Toul to Paris in around 1890. The father of the family, Louis-Alfred, opened a branch of the Blocq & Co. bank at 9 rue Vaneau in the 7th district of Paris. The family lived in the 8th district, first at 10 rue de Rome and then at 69 rue de Courcelles. Léon’s sister Georgette died in 1891 at the age of 6 ½. In 1900, when he was 17, Leon’s mother, Laure-Lucie Dreyfus, died.

Léon-Jacques graduated with a science-based baccalaureate and went on to study medicine, graduating 305th out of a class of 422 in 1902. A year later, however, he was called up for military service. He was drafted into the 13th Artillery Regiment on November 10, 1902, in which he began at the grade of 2nd Gunner. A year later, on October 7, 1903, he was placed on standby. At the time, military service lasted two years, and education was postponed. He therefore returned to his medical training in 1903, spending two years at the Pitié Salpétrière Hospital, one year at the Saint-Antoine Hospital and one year at the Cochin Hospital. His teachers, such as Mr. Walther and Mr. Vaquez, agreed that Léon-Jacques was “very diligent” and “a very good student”. Why, then, did he quit his course of medical studies so abruptly at the end of 1907? Might it have been because of the health problems revealed in his military service record?

In fact, in July 1910, the Seine reform commission proposed that he be assigned to the 23rd section of the military infirmary (SIM) on the grounds of tachycardia with cardiac hypertrophy.

From 1911 onwards, Léon-Jacques had a very varied and “turbulent” work life. He embarked on a political career, first of all under the presidency of Armand Fallières, as Deputy Chief of Staff to Mr. Jules Pams, the Minister of Agriculture. Then, in 1913, under President Raymond Poincaré, he was Chief of Staff to Mr. Jacquier, Under-Secretary of State for Fine Arts. In 1914, he was Chief of Staff to Mr. Jacquier, Under-Secretary of State at the Ministry of the Interior, still under the Presidency of Raymond Poincaré and the Viviani government.

Léon-Jacques, at the age of 56. Photo from his medical records from Villejuif.

Léon-Jacques Blocq and his political activities

- Article published in Le Petit Bleu de Paris on February 7, 1914, to mark the inauguration of a monument in Boucicaut Square.

2. Article published in l’Excelsior on April 12, 1914, on the occasion of the 24th Exhibition of the National Society of Fine Arts in Paris.

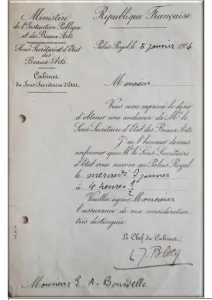

3. Letter from Léon-Jacques Blocq to Mr. Bourdelle Emile-Antoine, a famous sculptor.

Meanwhile, on June 18 1912, he married Lise-Nanette Ullmann, with whom he had two children: Antoine-Bertrand in 1913 and Anne-Marie in 1921. The couple divorced ten years later: Lise-Nanette and her little girl went back to live with her mother, and Antoine was raised by his grandfather.

In 1914, the First World War broke out. France mobilized all the men in the country at the beginning of August. On August 4, 1914, Léon-Jacques, in his capacity as chief of staff to the Under-Secretary of State for the Interior, was suspended from being called up until further notice. But on April 10, 1915, the suspension was cancelled. Owing to his health constraints, he was not sent to the battlefields, but remained in the auxiliary services. In 1918, he was assigned to the Bourges quartermaster’s office, then in 1919 to the Dijon quartermaster’s office. He was demobilized on March 15, 1919.

After the war, he ran unsuccessfully in the local government elections for the Loiret department. He did not go back into the civil service, and his professional career took a new turn, this time in journalism. Between 1922 and 1924, he wrote for the newspaper l’Eclair (Lightening) and was parliamentary editor of l’Ere nouvelle (New Era). Then, on April 8, 1924, he founded the newspaper LE BLOC, written by him alone, in which he exposed abuses of power in the law courts. In particular, he accused Mrs. Millerand and Raymond Poincaré of fraud. The 4-page journal, 2 of which featured advertisements, sold for 10 centimes. The head office was at 123 rue Montmartre. Léon-Jacques described his paper as being free from outside influence, independent and honest, and as publishing nothing but original material covering literature, theater, sports etc. and controversies. The paper was unfortunately discontinued after only three months.

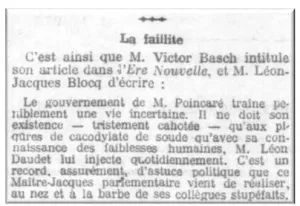

It’s clear from this excerpt from an article written for l’Ere Nouvelle and published in Le Libertaire (the Libertarian) on February 19, 1924, that Léon Jacques Blocq was an outspoken polemicist.

Article published in Le Libertaire (the Libertarian) on February 19, 1924.

Extract from the LE BLOC, founded and written entirely by Léon-Jacques Blocq.

Only copy held by the French National Library, issue no. 1, April 8, 1924. Ref. JO-46374

It was also in the early 1920s that Léon-Jacques Blocq’s mental health appears to have declined. He claimed that he was being hounded by Mr. Millerand, and felt that he was being watched. He openly accused Mr. Millerand and Mr. Poincaré of fraud and treason.

From 1923 onwards, the police took a close interest in Léon-Jacques Blocq’s conduct. The Prefecture drew up two reports on his behavior: the first, dated July 23, 1923, criticized Léon-Jacques Blocq for having boarded the presidential train during Mr. Poincaré’s visit to Villers-Cotterets. The other report, dated April 18, 1924, referred to his paper Le Bloc and his political articles.

On July 7, 1924, his father Louis-Alfred, his brother Maxime and his brother-in-law Léon Mascart asked the police department at Place Vendôme to commit Léon-Jacques to a mental institution, adding that he would not go voluntarily. On July 10, 1924, Léon Jacques was sent to a special infirmary and then, at the family’s request, to a private asylum on rue de Picpus. He was then transferred to the private asylum in Suresnes in August 1924. The police report stated that Léon Jacques was “suffering from delusions of persecution, delusions of a political nature likely to compromise public order or the safety of individuals“.

The hospital at Suresnes was one of eleven private asylums in the Seine department of France that the Police Commissioner had approved to take in insane patients. In November 1874, Gustave Bouchereau, Gustave Lolliot and Valentin Magnan had bought the Château de Suresnes and formed a company to set up and run a nursing home to treat patients with mental and nervous disorders. It catered for convalescent, nervous, exhausted, excited, neurasthenic and addicted patients. It had housed a number of famous and wealthy patients, including Alexandre Coquelin, actor and writer; Adèle Hugo; Boris Vian’s uncle; Baron Seillière; Louis-Lucien Klotz, a former finance minister; and Countess Hélène de Chateaubriand, who sued her family for wrongful confinement.

The Château de Suresnes, a private asylum in the Seine department of France

The Château de Suresnes, a private asylum in the Seine department of France

In September 1924, Léon-Jacques’ father requested that his son be released immediately. However, a forensic report drawn up by three specialists concluded that “Mr. Blocq is not cured, he is a reluctant and dissembling patient who endeavors to hide his delirium in order to secure his release, and he must continue to be treated”. Léon-Jacques Blocq did not leave the Suresnes asylum until February 1925.

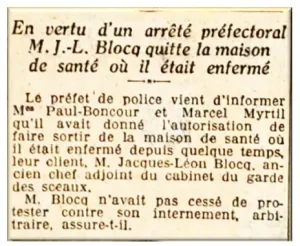

From the newspaper Le Matin, February 28, 1925

From the newspaper Le Matin, February 28, 1925

His release was, nevertheless, subject to conditions laid down by the Medical Inspector at the Prefecture: Léon-Jacques Blocq “should be entrusted to a member of his family providing reliable assurances, who will be responsible for the appropriate necessary supervision and guidance. Mr. Blocq and the said person must undertake to leave Paris immediately and spend several months in the south of France“. It was his lawyer, Mr. Myrtil, who was to take on this role.

Was Léon-Jacques Blocq really so mentally disturbed that he was committed to an asylum for seven months, or had he become too embarrassing for the government as a result of his allegations against high-profile individuals? His ex-wife, Lise Nanette, did not believe that her husband was crazy, as her interview in the February 8, 1925 issue of Le Petit Parisien newspaper shows.

Le Petit Parisien, February 8, 1925

In 1926, Léon-Jacques Blocq claimed damages from the Minister of the Interior for his internment, which he deemed to have been abusive. The government, however, dismissed his claim.

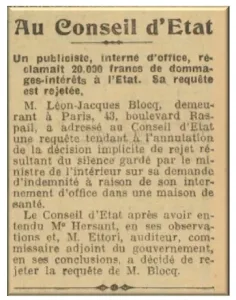

From L’œuvre newspaper, March 10, 1929

From L’œuvre newspaper, March 10, 1929

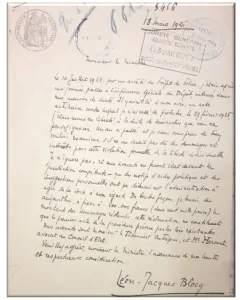

Handwritten letter from Léon Jacques Blocq to the Minister of the Interior, claiming damages following his internment. Letter dated March 18, 1926

Handwritten letter from Léon Jacques Blocq to the Minister of the Interior, claiming damages following his internment. Letter dated March 18, 1926

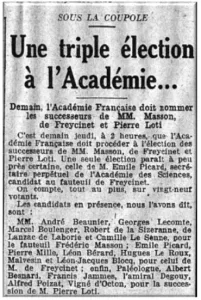

While he remained a patient in the Suresnes asylum, the November 27, 1924 issue of L’Intransigeant newspaper revealed that Léon-Jacques Blocq was a candidate for the Académie Française (the French Academy, the principal French council for matters pertaining to the French language). Three seats were up for election, those of Mr. Masson, Mr. Freycinet and Mr. Pierre Loti. Léon-Jacques ran to replace Mr. Freycinet, but in the end, it was the mathematician Emile Picard who won.

In April 1928, he tried to return to politics and ran as a Republican candidate in the parliamentary elections in the 2nd constituency of the 20th district of Paris, but once again, he was unsuccessful.

After that, Léon-Jacques Blocq appears to have moved on to a new line of work: on his 1938 voter’s card, he is listed as a publicist living at 26 avenue Montaigne in the 8th district of Paris. His health was delicate and, at the age of fifty, he was treated for septicemia, pleurisy and pneumonia. The police appear to have forgotten about him since the beginning of the decade, but he was back in the news in 1939. At home, he was accused of shouting, swearing and causing a disturbance, and his landlord started eviction proceedings. In the street, he insulted unknown passers-by, jostling them and using foul language. In September 1939, he was arrested following a public scandal. Exasperated by having to show his identity papers so often on the street, he lashed out at a police officer, telling him that he would be better off on the Maginot Line.

On September 27, 1939, he was once again interned in a special hospital and then in the Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital in Paris. The doctors said that he was « suffering from delusions of persecution and morbid imaginings”. As he had in the 1920s, he felt he was being followed, and kept repeating ” They have their orders “, ” ask the people who are watching me “. In December 1939, he was transferred to the Ville-Evrard nursing home in Neuilly-sur-Marne, where he remained until May 12, 1940. He then spent 15 days at the Villejuif hospital, where Dr. Rogues de Fursac described his patient as “a subject of unbalanced mind”. Germaine, Léon-Jacques’ sister, wrote to the doctor asking for her brother to be transferred back to the Ville-Evrard nursing home. The Prefecture agreed to her request, and Léon-Jacques was once again interned at the Ville-Evrard nursing home, where he remained until March 23, 1942.

On March 24, 1942, Léon-Jacques was transferred to the Villejuif psychiatric hospital in order to be closer to his family in Paris.

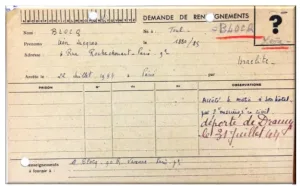

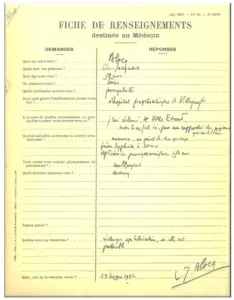

Léon-Jacques’ medical form, on admission to the Villejuif psychiatric hospital

Léon-Jacques’ medical form, on admission to the Villejuif psychiatric hospital

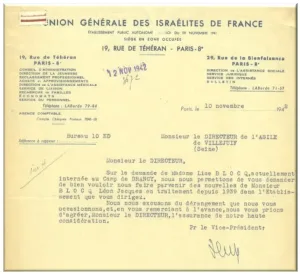

In November 1942, the Union Générale des Israélites de France (General Union of French Jews) sent a letter to the manager of the asylum. It says that Lise Nanette, Léon Jacques’ ex-wife, who was interned in Drancy camp, was asking for news of her husband.

Léon-Jacques Blocq remained in Villejuif throughout 1942, during which time his health improved. When his patient first arrived, Dr. Abely described him as “suffering from constitutional mental imbalance with excited and querulous periods“. A few months later, however, he reported that he was “calm and disciplined in the ward”, and that there were “no delusions at present“. On November 7, 1942, the Seine civil court ruled that Léon-Jacques Blocq “shows no signs of any mental illness and can be released without danger to himself or others”. His mental assessment showed him to be “cultured, with fluent, clear language, a good memory in all respects, with a rapid train of thought involving mild intellectual excitement“. He was freed on January 31, 1943.

While the doctors agreed that Léon-Jacques Blocq should leave the asylum, the same could not be said of the Police Department, who were hesitant to release him. Their representatives in court explained to him that the time was not right, and that given his temperament and ethnic origins, he risked exposing himself to danger and ending up in a concentration camp at the first sign of trouble. But Léon-Jacques Blocq was unmoved by this argument, stating that he “wanted to live quietly, without getting into trouble, and that he had no enemies likely to harm him at the moment“.

It turns out that Léon-Jacques Blocq would have been safer if he had stayed in the Villejuif psychiatric hospital for the duration of the Occupation. On July 22, 1944, “two gentlemen in civilian clothes” arrested him at his hotel and took him to Drancy camp. He was assigned the number 25347. Nine days later, on July 31, 1944, Léon-Jacques Blocq was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. On October 12, 1962, however, the Seine High Court declared that Léon-Jacques Blocq had died in Drancy on July 31, 1944.

Lise Nanette Ullmann, Léon-Jacques Blocq’s wife

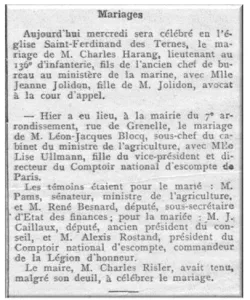

Lise Nanette was the daughter of Emile Samuel Ullmann, the director and vice-president of Comptoir National d’Escompte (the French National bank at the time), and Marguerite Levy. She had one older brother, named Claude.

In 1912, she married Léon-Jacques Blocq, who was at the time the deputy chief of staff to the Minister of Agriculture. They got divorced ten years later.

Marriage announcement in the French newspaper GIL BLAS on June 19, 1912

Lise Nanette was an artist: she was a painter and enamel artist. She studied with Suzanne Minier and F.Humbert. In the French dictionary BENEZIT, which lists painters, sculptors, illustrators and engravers from all over the world, it says that Lise Nanette Ullmann won a distinction at the Salon des Artistes Français (French Artists’ Exhibition) in 1910. She subsequently exhibited a painting entitled “L’intérieur” (The Interior) in 1913, followed by “Chez la fleuriste” (At the florist) in 1914.

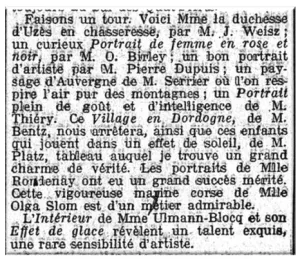

Article in the French newspaper L’Echo de Paris on April 29, 1913

Article in the French newspaper L’Echo de Paris on April 29, 1913

The French journalist Eugène Tardieu was full of praise for Lise Nanette’s work, which was exhibited at the Grand Palais alongside 1,878 other paintings: he noted her “exquisite talent” and “rare sensitivity as an artist“.

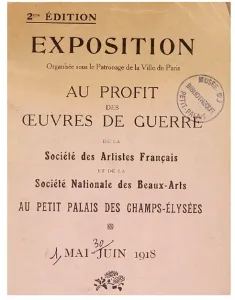

In 1918, in support of wartime charities, she exhibited a painting at the Petit Palais entitled “Intérieur d’écurie” (Interior of a stable). Some of her other paintings were called “Pont à Venise” (Bridge in Venice) (1913) , “Fleurs” (Flowers) (1914) and “La serre” (The glasshouse) (1914).

We discovered that an auction held in 2017 at the Royan auction house included a painting by Lise Ulmann Blocq. It was an oil painting on canvas called “Barque sur un lac” (Boat on a lake), signed on the bottom right and dated 1921, but we do not know if it was sold.

On October 22, 1942, German police from the Avenue Foch department arrested Lise Nanette Ullmann at her home at 90 rue de Varenne. The concierge’s testimony states that she used the name Lise Eran. She was taken to Drancy camp, where she was assigned the number 17167 and placed in Block IV, staircase 15, room 10. When she arrived, she handed over a sum of 100 francs. Although she had been divorced for twenty years, the money was sent to her ex-husband, Léon-Jacques, who was interned in Villejuif hospital at the time, on October 24, 1942.

She was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp on July 18, 1943 on Convoy 57. The train was made up of 23 freight cars and 3 passenger cars, one behind the locomotive, a second in the middle of the train and a third at the rear. At 9:30 a.m. on July 18, 1943, the convoy, which was carrying 1,000 Jews, left the Bobigny station in the north of Paris bound for Auschwitz. Around 20 policemen from the Saarbrücken Orpo (Ordnungspolizei, police) travelled with the deportees.

Sim Kessel, who was arrested in Dijon, testified that the deportees remained calm at the start of the journey. Before the train left, the Germans had assigned one of them to be responsible for maintaining order. On the second day, the thirst was unbearable. The deportees ate a few leftovers. Some of them shared some dry, sour bread, while others shared stale cookies that were no longer fit to eat.

Maurice Szpirglas, who was arrested in April, testified: “There were sixty of us in the car […] we were sitting like sardines. We traveled for three days and two nights […] the atmosphere was atrocious, the stench atrocious, it was unbearable.”

When the convoy arrived at Auschwitz, 369 men were selected for forced labor. They are tattooed with the numbers 130834 to 130466. In addition, 191 women were selected to work and assigned the numbers 50204 to 50394. The remaining deportees were killed in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived at the camp. Lise Nanette Ullmann was among them.

In 1945, only 30 men and 22 women from the convoy were still alive. (source: yadvashem.org)

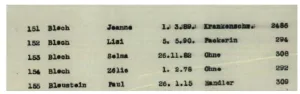

Extract from the deportation list. (source: Arolsen archives)

Extract from the deportation list. (source: Arolsen archives)

On the deportation list, the Germans spelled her first name “Lisi” and listed her occupation as “packerin“. This was no doubt a misinterpretation of the job “enameller”. Another card lists the foodstuffs transported in the freight car, and says “do not use high-quality foodstuffs for concentration camp catering“, meaning foods such as chocolate, red wine, sugar, meat and jam.

At the end of the war, Lise Nanette Ullmann’s death was recorded as having taken place on October 22, 1942 in Drancy. However, a judgment published in the Journal Officiel (French official gazette) on June 6, 2001 officially recorded her death as having taken place on July 23, 1943 in Auschwitz, i.e. five days after the train left Bobigny station.

Léon-Jacques Blocq and Lise Nanette Ullmann’s children

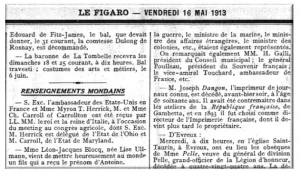

On May 16, 1913, an advertisement in the newspaper Le Figaro announced the birth of Léon Jacques Blocq and Lise Nanette Ullmann’s first child, Antoine, who was born on May 4 in the 17th district of Paris.

Antoine went on to work as an accountant, but he also wrote a law thesis at the University of Poitiers in 1956, at the age of 43, entitled “Overview of German legislation on the equalization of charges and its impact on foreigners and their property“.

Antoine was prosecuted twice. The first time was at the Seine Correctional Court on October 8, 1941, for handling stolen goods. The judgement stated that he had “fenced two stolen bicycles”. He was given a 6-month suspended sentence and fined 25 francs.

The second ruling was handed down on March 31, 1944 by the 12th chamber of the Seine District Court. Antoine was charged with refusing to comply with the formalities of the census of Jews. He had “failed to make a written declaration within the prescribed time limit, stating that he was a Jew as defined by law, and to list his civil status, family situation, profession and assets“. In addition, he was using a forged identity card. Two laws, dated October 27, 1940 and June 2, 1941, had been breached. Antoine was sentenced to eight months in jail.

He was initially imprisoned at the Maison d’arrêt de la Santé (Santé detention center) in the Montparnasse quarter of the 14th district of Paris, from February 18 to April 13, 1944. Then, from April 15 through 20, he was transferred to the Tourelles prison, a barracks located at the Porte des Lilas in the eastern suburbs of Paris. Between 1940 and 1945, the barracks had a singular vocation

It was first used to accommodate refugees who were fleeing the advancing Germans in May-June 1940, and from July 1940 onwards, it took in foreigners who were not usually authorized to stay in the Seine department, but who were unable to leave due to the circumstances. Some 1,500 men, women and children were housed there until July 1941. At the end of October 1940, the Police Headquarters set up an internment camp there, with supplies provided by the Seine Prefecture and armed guards provided exclusively by the French Gendarmerie (Military Police). When the Third Republic came to an end, the camp was initially used to hold “undesirable” foreigners, communists and convicts. Under the Vichy regime, it was expanded to include foreign and then French Jews, persons in breach of financial regulations, draft dodgers and, potentially, anyone else.

He completed his sentence at the Clairvaux prison, where he was held from April 20 to August 18, 1944. The prison register states that Antoine was released on August 18, 1944, and that he went to Clermont-Ferrand, where some of his family were already living at 17 rue Marmontel.

In 1957, Antoine married Doris Maria Köllisch in Karlsruhe, Germany. We found no record of their having had children.

Antoine died in June 1968 in Kinshasa, Congo, where he was a professor at the Ecole Nationale de Droit et d’Administration (National School of Law and Administration). His body was repatriated to the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris on September 10, 1968.

Léon Jacques Blocq and Lise Nanette Ullmann also had a daughter, Anne-Marie, born on August 16, 1921.

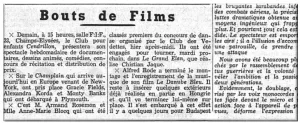

Anne-Marie, like her mother, appears to have pursued a career as an artist, as an article in the February 5, 1939 issue of L’Intransigeant states that she and Mr. Armand Rosemon won 1st prize in a dance competition organized by the Club des Vedettes, and that both were hired to star in Christian Jaque’s film Le Grand Elan.

During the Second World War, Anne-Marie appears to have fled to England. She returned to France in 1947 and, together with her brother, desperately searched for her parents. She looked for signs of them in Africa and Europe, only to discover their tragic demise. Eventually, in 1957, she applied to the French Ministry of Veterans and Deportees to ask whether she and her brother could claim compensation for the deportation of their parents. The Ministry paid each of them 60 French francs in 1962, which was described as “payment of compensation to dependents of political deportees or internees who died while in detention or after they were repatriated”.

Anne-Marie married Jean Braunschweig on May 13, 1977, in the 17th district of Paris. She died on August 3, 1980 in Neuilly-sur-Seine. There are no records to suggest that the couple had any children.

Conclusion

The Blocq family from Toul, as mentioned on the tombstone in the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris, included many eminent family members who devoted their lives to serve France. The family also knew and worked with many well-known figures in French history.

Starting with Léon-Jacques’ father, Louis-Alfred, Knight and Officer of the Legion of Honor, who took part in the siege of the town of Toul during the 1870 war against Prussia and then proved his dedication to his country by setting up the Soldiers’ Center at the beginning of the 20th century. He also became involved in the Dreyfus affair, raising funds for the Syndicat, a union that campaigned for justice and was also backed by the famous writer, Émile Zola.

Starting with Léon-Jacques’ father, Louis-Alfred, Knight and Officer of the Legion of Honor, who took part in the siege of the town of Toul during the 1870 war against Prussia and then proved his dedication to his country by setting up the Soldiers’ Center at the beginning of the 20th century. He also became involved in the Dreyfus affair, raising funds for the Syndicat, a union that campaigned for justice and was also backed by the famous writer, Émile Zola.

Léon-Jacques’ sister, Germaine, saved many lives as a staff nurse at the Auxiliary Hospital in Maxéville during the First World War. She took the risk of exposure to the Spanish flu epidemic, for which she was awarded the Vermeil medal by the French Ministry of War. She was also deeply involved in the Red Cross youth section and the Hygiene by Example organization. During the Second World War, she was instrumental in implementing a project put forward by Jean Zay, the Minister of Education under the Front Populaire (Popular Front), by founding field centers in the countryside to take in children who had been evacuated from the cities.

Léon-Jacques’ brother, Maxime Blocq-Mascart, made a name for himself in the French Resistance during the Second World War. Under various aliases, he went underground in 1943 and became head of the Civil and Military Organization. He was also a permanent member of the National Resistance Council. He was also awarded honors including Knight of the Legion of Honor, the Resistance Medal and the War Cross.

As for Léon-Jacques Blocq himself, “cultured, with fluent, clear language, a good memory in all respects, with a rapid train of thought involving mild intellectual excitement“, he had a very varied and eventful professional and personal life. A brilliant medical student, he opted to begin his professional career in politics. As a young man, he rubbed shoulders with two Presidents of the Republic: Armand Fallières and Raymond Poincaré, and put his talents to work in the offices of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Fine Arts. He was a prominent figure, presiding over inaugurations and Parisian exhibitions. He then pursued a career as a journalist and publicist, and founded his own newspaper, LE BLOC, although it only survived only a few months. What are we to make of his many stays in psychiatric hospitals? Was Léon-Jacques really suffering from psychiatric problems, or was he too embarrassing a character for the government due to his allegations against high-ranking public figures? Doubts were expressed by his wife, Lise-Nanette, a renowned painter and enamel artist.

The Blocq family tree

Français

Français Polski

Polski