Biography of Fanny Marthe LUZZATO, née WEIL (1882-1944)

Simone ZIMBARDI, M1 Archives 2017/2018, Student N°: 17806882,

under the direction of Professor Marie-Anne MATARD-BONUCCI

Université Paris 8, Vincennes-St Denis

Seminar « The Archives of the Shoah »

Table of Contents:

- Mademoiselle Weil (1882-1903)

- Mme Luzzato (1904)

- The joys of maternity, the sorrows of war (1905-1919)

- Putting her life back together (1920-1939)

- Humiliated, dispossessed, interned (1940-1943)

- “Died for France” (1944)

Abbreviations of the archives

Bibliography

Annexes

Encounter with Philippe Bouvard

Chronology

Genealogical trees

-

Mlle Weil (1882-1903)

Fanny Marthe Weil was born at Dambach-la-Ville in the Bas-Rhin department of Alsace on December 17, 1882[1]. She was the eldest daughter of Henri Weil, a wine merchant, and Clémentine Schill, housewife [2]. Her father’s family was native to Dambach-la-Ville, which was just a small village of 3132 inhabitants[3]. A large, mostly merchant Jewish community – around 300 in the middle of the 19th century —settled there in the Middle Ages[4].

Fanny belonged to a quite respectable family in Dambach-la-Ville. Her paternal grandfather was Rabbi Seligmann Weil. A Talmudic scholar, he was posted in Versailles during the difficult period of the Franco-Prussian War. He energetically resisted the decision of the rabbi with the German Jewish troops to have them pray for the German emperor William I. Seligmann died young on October 4, 1870 at the age of 54, twelve years before the birth of his granddaughter[5]. He was survived by his wife, Babette Süsskind, who died on July 17, 1893 at the age of 77. [6].

Rabbi Weil and his wife had several children; Fanny’s father Henri was the second of them. He was born in Dambach-la-Ville on October 17, 1846[7]. As for Fanny’s mother, Clémentine Schill was born to a Jewish family in the Lorraine town of Neunkirch on March 14, 1858. The daughter of Joseph Schill, a man of independent means, and of Julie Kahn (known as Mathilde)[8], she married Henri Weil on February 27, 1882 in the Lorraine city of Sarreguemines[9]. The couple had four children: Fanny, the eldest, Nanette, who was born in Dambach-la-Ville on February 22, 1884[10] and died shortly thereafter in the same town on October 17, 1885[11], Seligmann, the couple’s only male child, born on February 29, 1886, also in Dambach-la-Ville[12], and lastly Hélène, born in Sarreguemines on January 17, 1890[13].

Fanny spent her early years in Dambach-la-Ville. In the Alsace-Lorraine census of December 1, 1885 she is listed as living with her parents, her maternal grandmother Babette, and the maid, Sophie Spitz, at 57 Langgasse. The grandmother was, however, away in Strasbourg at the time of the census[14]. In1888 the little girl moved with her family to Sarreguemines (where her parents had already resided), a larger town counting 13,076 inhabitants in 1891[15]. She spent the rest of her childhood and her adolescence there before going to Paris to start her new life on October 15, 1903 [16].

Fanny’s family was strongly drawn to the French capital, especially her maternal family, most of whom were merchants. So it was to Paris that a good many members of the Schill family moved between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, to establish there their professional activity and their residence. From the time she arrived in Paris Fanny (21 years old at the time) could count on the material support of her uncles.

Fanny’s brother Seligmann had been living in the capital since December 1902[17], but then her mother Clémentine and her younger sister Hélène also came in 1904[18] and were taken in by their relatives at n° 7 rue d’Abbeville in the 10th district. In 1904 a large part of the Schill family was living at that address, including Fanny’s aunt Nanette and her son Armand, and Joseph, Fanny’s grandfather.[19].

Also in Paris were Fanny’s maternal uncles, starting with Louis Schill. Joseph’s younger brother, he married his niece Nanette in 1873. In addition to being a salesman for cardboard packaging in Paris’s 4th district[20], Louis was a transit agent, particularly involved in importing elastomer from Brazil [21]. He presumably worked with at least one of his wife’s brothers, David Schill, a deputy consular agent in Manaus, Brazil. There was a French colony in that international rubber trading town[22], made up mostly of merchants like Fanny’s uncle[23]. From at least the end of the 19th century the Schill family owned real estate in Manaus[24], which would eventually be inherited after the war by Fanny’s son Jules[25].

Louis died on March 28, 1903 at n° 32 boulevard de Strasbourg in Paris’s 10th district, most probably one of his residences[26]. It is interesting to note that at the same address another of Fanny’s maternal uncles, the wholesaler Adolphe Schill, set up his own import company, the Maison Schill et Kahn, on January 2, 1904.[27]. No doubt taken in by her uncles, Fanny was domiciled at that address from the time she arrived in Paris[28].

It is certainly no coincidence then that the young lady began work as a cardboard worker, by definition “a worker in the paper manufacturing industry who manually assembles cardboard boxes”[29]. It is likely that her uncles’ influence in this area of activity, especially that of the family of the cardboard packaging salesman Louis Schill, helped the young woman get this job

It is also possible (but this is only a hypothesis) that it was in the Parisian community of Jewish merchants in the 9th and 10th districts that Fanny met her future husband, Sigismond Luzzato, an Austrian Jew who had taken French citizenship. Through her marriage Fanny herself became a French citizen.

-

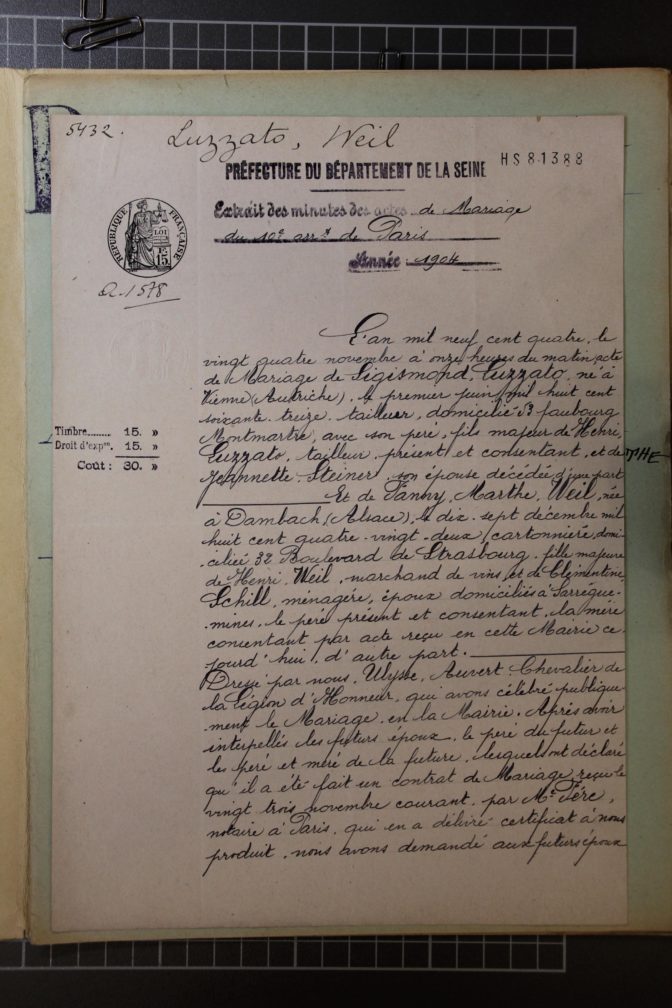

Mme Luzzato (1904)

Sigismond, known as Simon, Luzzato, nine years older than Fanny, was born in Vienna, Austria on June 1, 1873 to Henri Luzzato and to Jeanette Steiner, who died on December 21, 1888 at the age of 42 [30]. He was granted French citizenship on December 20, 1903[31]. His father Henri, born on September 25, 1842 in Pazzossy, Hungary[32], came to Paris with his wife, who was a seamstress, and their children between 1874 and1876[33]. In 1886[34] Henri set up shop as a tailor of men’s clothing (working for private customers and selling the clothes himself) on the rue du Faubourg Montmartre in the 9th district of Paris, where in the early years of the twentieth century he established permanent residence for his family and his business at number 53[35]. It was at this address that Fanny was to spend the rest of her life.

Henri’s decision to set up business in the Faubourg Montmartre neighborhood was hardly incidental; in the 19th century it was inhabited by a great many Jews who came from central and eastern Europe and chose to establish their commercial activities in that district[36]. But while during the day the rue du Faubourg Montmartre, the very heart of the neighborhood, was “honest, industrious and mercantile”, the evening saw it fill up with “pimps, con-men, bookmakers, scholarship students, and hookers”, making the district noisy and vibrant, perhaps even dangerous [37].

It would seem that at the turn of the century Henri Luzzato’s business was prospering. In 1903 it employed ten workers, including Sigismond, who lived and worked with his father from 1902 on[38]. On November 30, 1903 Henri and Sigismond founded the company “Luzato et Fils”, making Sigismond his father’s partner[39].

So the economic outlook was sunny when Fanny and Sigismond signed their marriage certificate before the notary Albert Peré at n° 9 place des Petits-Pères in the 2nd district of Paris. The ceremony took place the next day at 11 a.m. at the Tenth District Town Hall [40]. Henri Luzzato was the only parent present, his wife Jeanette being already deceased and Fanny’s mother Clémentine no doubt gravely ill, as she was to die a few days later on November 28th[41]); as for Henri Weil, he was most probably still residing in Sarreguemines for business reasons.

Fanny and Sigismond’s witnesses, all of Jewish origin and all belonging to the Luzzato and Weil families, worked in commerce, testifying to the very tight bonds that linked the newlyweds to that milieu. Isidore Goldenberg, a tailor aged 25, and Jean Draselchick, 30 years old (no stated profession), were merely Sigismond’s brother-in-laws. The former was married to Hélène[42], the latter to Pauline Luzzato[43]. The other two witnesses were two of Fanny’s maternal uncles, Michel Polack, a 52-year-old merchant who had married Hélène Schill, one of Fanny’s maternal aunts, and 40-year-old Adolphe Schill, also a merchant.

Marital bliss was cut short only a few days after the ceremony; Fanny’s mother Clémentine passed away in Paris at the age of 46 on November 28, 1904[44]. This was to be just the first of a long series of mournings that struck Fanny in the next years.

-

The joys of maternity, the sorrows of war (1905-1919)

Married in November 1904, Fanny had only one child with her husband; Jules was born on April 30, 1907 at 4:00 a.m.[45]. This event was to mark a radical change in her life, magnified by her husband’s liquidation of “Luzato et Fils”. He took over the management of all the Luzzatos’ commercial activity, setting up his own company, still at n° 53 rue du Faubourg Montmartre, with five partners[46].

Like most women of the commercial bourgeoisie, Fanny stopped working when her first child was born. We picture her devoting her days to her son, but also, unfortunately, to her bereavements. On February 3, 1909 her maternal grandfather, Joseph Schill, died at the age of 80[47]; the following year on January 22, 1910 her maternal uncle David died at the early age of 41[48].

On the other hand, in the midst of all this sorrow Fanny celebrated the marriage of her younger sister Hélène, who married the merchant Louis Joseph Lévy on April 4, 1911[49]. Sigismond figured among the four witnesses. It is noteworthy that the three other witnesses also belonged to the merchant world. Samuel Lévy was a hatter; Justin Lévy was a clothing manufacturer; Adolphe Schill, Fanny and Hélène’s uncle, was a merchant[50].

The eruption of the First World War in 1914 violently affected Fanny’s daily life. Her status as a former German national risked causing her trouble, and even more especially as she was not married to a Frenchman, but only to a naturalized ex-Austrian (Austria being allied to Germany in the war) [51].

Surveillance of the foreigners in France was instituted by the Ministry of the Interior in September 1914, and at the request of the Ministry dated February 3, 1915 the Police Préfecture carried out an enquiry on Fanny[52]. After her home was visited by the police, the Préfecture reported to the Ministry that “the lady Luzzato (…) is not interned. She is still domiciled at n° 53 rue du Faubourg Montmartre and her health seems satisfactory. Her husband (…) is mobilized”[53]. The three pages of this letter are reproduced at the end of this document.

Sigismond had had to leave his family to be inducted into the army[54]. In February 1917 he belonged to the 13th territorial battalion; then he was incorporated into the Oriental Expeditionary Corps for the Salonica expedition, during which he was appointed quartermaster corporal (an administrative post in the army) on January 29, 1918. Captured by the enemy, he was freed on January 22, 1919 and returned to Paris, a wounded, 10% disabled veteran. For his merits at the front he was awarded a commemorative medal by the French state[55].

During the dark years of the war Fanny also suffered the death of two of her closest relatives. In April 1915 her father Henri died at the age of 69[56]. The following year, on October 16, 1916, it was her maternal aunt Nanette who passed away at the age of 60 at her home in Montmorency[57]. However, before she died Nanette had a will made out in which she left her niece Fanny a nice holiday residence in Montmorency, the villa “Les Mésanges”. In 1910 she had purchased the house, built at the end of the 19th century, [58]. There was, though, a very strict clause in the will: Fanny was to be sole owner, and was neither to sell or rent it to anyone outside the family[59].

Located on the rue du Parc Séchan in one of the bourgeois neighborhoods of the town, the house measured about 1000 square feet and was described at the time of probate as being “built in millstone over cellars and consisting of an entry, a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, toilet and large veranda on the ground floor, with three bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs, a full-size attic, and a garden”[60].

-

Putting her life back together (1920-1939)

Once the war was over the Luzzato family could take up its daily life again. Sigismond, though wounded, was able to come back to France. After returning to his professional activity he began teaching Jules, who would be the Luzzatos’ third generation in the family enterprise. Jules had already begun his apprenticeship in 1926 (at the age of 19), when the census was taken of the population of Paris. He is mentioned as “working as a tailor”, whereas Sigismond is put down as a “tailor”, i.e. a boss[61].

As for the elder Henri Luzzato, who was 84 by this time, he is also catalogued as “working as a tailor” in that census[62]. Presumably, however, his health in 1926 was weak; he passed away on June 11 at his home[63]. The former head of the family’s death had no effect on the Luzzatos’ professional activity. On the contrary, the earnings of the enterprise allowed the Luzzatos to hire servants to take care of their domestic tasks. From 1926 and at least until 1931 they had at their disposal an in-house Alsatian cook named Anne Knecht[64]. From 1936 at the latest the Luzzatos had a new servant, a young chambermaid named Marcelle Thibault, instead of Madame Knecht.[65].

Toward the end of the 1930’s Fanny celebrated the marriages of her brother Seligmann and her son Jules. The former, a salesman like most of his relatives[66], was married on December 23, 1937, by that time already 51 years old, to Madeleine Elisabeth Dumora[67], a widow whose first marriage had been to Alcide Jean Valtaud[68]. Their union had remained childless[69].

As for Jules, on March 3, 1939 he married Andrée Gensburger at the town hall of Paris’s 9th district[70]. She was Jewish, born in 1904, and employed in sales at the time of her marriage. Andrée was divorced from her first husband, Marcel André Bouvard[71], who had abandoned her when she was pregnant. In 1929 she gave birth to his son Philippe, who is a journalist with the RTL radio network. Monsieur Bouvard has always considered Jules as his father, having seen his biological father only once in his whole life, and grown up in the care of Jules and the Luzzatos [72].

The marriage of Jules and Andrée produced two daughters, Claudette, born in the 16th district of Paris on November 10, 1942, and Anne Marie Clémentine, born in the 9th district on September 14, 1944[73]. But Fanny was not to enjoy her growing family and watch her great-nieces, both of whom were born during the dark years of the Nazi occupation of France and the persecution of the Jews, grow up.

-

Humiliated, Dispossessed, Interned (1940-1943)

At the beginning of the 1940’s, all throughout France the Vichy regime and then the Nazis undertook an ever more ferocious persecution of the Jews. Fanny and her family were not spared by this veritable anti-Semitic obsession.

From the very start of the war Jules enlisted against the German enemy. A short time after his marriage he was mobilized as a volunteer in the vain attempt to prevent the German troops from advancing into French territory[74]. Back in Paris he obtained a Voluntary Service medal[75]. In the following years he kept up the fight, not on the battlefield, but in his workshop.

Despite the hardships of the period the Luzzatos’ enterprise seems to have continued to function at the beginning of the occupation. Certainly well-known internationally, as Monsieur Bouvard has pointed out, it could boast among its customers the sultan of Morocco, Mohammed V, “the glory of the shop”, who was close to the Paris Moslem community, with which Jules’ wife was involved socially [76].

At any rate it was presumably Jules who was managing the business during these years. Indeed, starting on October 1, 1940 political pressure prevented Sigismond from working as a merchant, allowing him only his activity as a custom craftsman, as is indicated by an inspection carried out by the Tax Office[77]. No longer the boss of his own shop, he worked as an ordinary worker from his home[78], on the fourth story of the building at n° 53 rue du Faubourg Montmartre, for “The Sport”, a company located at n° 17 Boulevard Montmartre, and for a tailor shop, “Fernand Bardet”, at n° 21 rue Saint-Marc[79]. Philippe Bouvard, replying to questions about his adoptive grandparents on February 5, 2018, confirmed that Sigismond was working at home at that time.

Fanny and Sigismond helplessly watched themselves being dispossessed of their real estate holdings, according to the provisions of the law of July 22, 1941 on the Aryanization of Jewish property. In 1941 their lovely country house in Montmorency was taken away from them, and the following year the family’s commercial activity, its chief source of revenue founded 50 years earlier by Fanny’s father-in-law, was seized.

On October 21, 1941 Georges Retif, a man living in Sartrouville, was appointed provisional administrator of “Les Mésanges”, the country house Fanny had owned since inheriting it from her maternal aunt Nanette in 1916.[80]. However, Monsieur Retif was apparently unsatisfied; as the house in Montmorency was a vacation home it was unprofitable, and he requested that the allotment should be annulled. The next month, on the 20th of November, he wrote to the General Commissariat for Jewish Questions (CGQJ), which was in charge of administering the patrimony of the Jews of France. “…I have the honor of requesting you to relieve me of my functions, as this property generates no revenue. Consequently, I would respectfully ask you to determine my fees”. They were finally set by the CGQJ at 800 francs[82] and paid to the provisional administrator by the Luzzatos on December 10, 1941[83].

Again in the alarming context of the Aryanization of the patrimony of the Jews, the Luzzatos’ business activity was attributed on May 4, 1942 to a provisional administrator, Paul Aspord, a Parisian with a law degree[84]. In the following months the business sank so far that it could no longer bear the flat fee of 500 francs due for the services of the provisional administrator. The sum, along with the management expenses (385 francs) was paid to Monsieur Aspord by the CGQJ in February 1944[85].

Meanwhile, in 1942 – the terrible year when Germany decided to undertake the “final solution” everywhere – the situation of the French Jews became dramatic, as anti-Semitic propaganda got ever more fierce. “The summer of 1942 was obviously marked by the major roundups in the Paris area in mid-July“.[86] It was during this brutal persecution that the Luzzatos’ home was searched and they were arrested by the French police. Sigismond was interned in the Cherche-Midi prison on July 10; he did not get out until December 21, 1942 [87]. On July 12 Fanny was also arrested and jailed in the Fresnes prison. She remained there for more than five months[88] and was let out on December 21, the same day as her husband.[89].

As for Jules, we have the precious testimony given by Monsieur Bouvard to the journalist, Mohammed Aïssaoui, who in 2012 reconstructed the role played during the years of persecution in support of the Jews by Si Kaddour Benghabrit, founder of the Great Mosque of Paris and director of the Muslim Institute of the Great Mosque from 1926 to 1954,.[90].

Having already been involved militarily against the enemy in the early 1940’s, Fanny’s son pursued the fight using his tailoring skills to make civilian clothing for German deserters. But then one day, as Monsieur Bouvard recalls, “the Wehrmacht caught one of those deserters, who gave Jules’ name. My father was incarcerated in the Santé prison [in central Paris][91]. I believe it was during 1942. My mother went to seek Si Kaddour’s help, as he was reputed to be a kind-hearted and influential man. He was one of the few who, because of his position and stature, could talk to the Germans while appearing to be neutral. My mother told him her troubles. Two weeks later my father was set free”[92]. Thus Jules obtained his liberation through the intercession of the influential Si Kaddour Benghabrit. In this case it was as a personal favor, for Jules’ wife was a close friend of Monsieur Benghabrit[93].

At the end of 1942 Fanny could again embrace her son and her husband. Nevertheless, the situation of the Luzzatos and the Jews of France remained extremely critical. On this subject Monsieur Bouvard recalls that during these uncertain years “my mother and I (…) hid ourselves, changing our dwelling at least ten times”[94]. By hiding, her son’s family managed to escape deportation, but Fanny was not to be so lucky.

-

“Died for France” (1944)[95]

Even though 1942 was the gravest of the years of the Jewish ordeal, the exactions and deportations were to continue in 1943 and 1944″[96]. They went on throughout France at a frightening pace, even though the Allies had landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. Paris was not liberated until the 19th to the 25th of August. Fanny, by that date, was already dead.

It is easy to picture Fanny and Sigismond in that terrible year of 1944, worn out and terrified after their harsh 6-month captivity two years earlier. But they were, in addition, aging and ill (Fanny was 62 and Sigismond 71), as Monsieur Bouvard recalls, and that is why they did not try to hide with Jules’ family. They hadn’t the strength to withstand the violence of the war.

The couple was finally arrested at their home on July 12, 1944[97]. On the next day the Luzzatos were sent to the camp at Drancy; Fanny was transferred to sector 18.2 and allotted deportee number 25103[98]. Finally, on July 31 she took her place with more than 1300 other people, including her husband, in convoy 77, the last big deportee convoy from Drancy, whose final destination was Auschwitz[99].

Neither Fanny nor Sigismond had any chance of surviving deportation. Too old for forced labor in the camp, they were no doubt among the 847 prisoners murdered upon arrival at Auschwitz. Their official death certificates carry the date August 15, 1944. A few days later Paris was at last liberated by the Allies. The war was almost over.

After the war Jules was finally able to locate his numerous relatives who, like him, had eluded deportation. In fact, by inspecting Fanny’s family tree it can be seen that the entire family, or nearly all, survived the war.

Jules then had to deal with his parents’ large estate. As the only heir he entrusted the management of the inheritance to the notary Paul Jullien (9 Place des Petits-Pères, Paris 2e)[100]. On November 14, 1945 Jules was named sole administrator for the family’s commercial activity. He took back ownership of his property after an out-of-court settlement with the ex-administrator, Monsieur Aspord, in the following months[101]. However, the Luzzato enterprise was to remain open for only a few more years. Jules ceased all activity on February 28, 1952, sixty-six years after the foundation of the shop by his grandfather [102]. He died in 1974, thirty years after his parents.

Abbreviations of the archival sources

- ADBR : Archives Départementales du Bas Rhin.

- ADMP : Archives Départementales et Municipales de Paris.

- ADVM : Archives Départementales du Val-de-Marne.

- AMS : Archives Municipales de Sarreguemines.

- AN : Archives Nationales.

- ANé : Archives Nénert.

- AONACVG : Archives de l’Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre.

- MS : Mémorial de la Shoah.

Bibliography

- Aïssaoui Mohammed, L’étoile jaune et le croissant, Paris, Gallimard, 2012.

- Azéma Jean-Pierre et Bédarida François (dir.), La France des années noires. Tome 2 : de l’Occupation à la libération, Paris, Seuil/Points-Histoire, 2000.

- Blumenkranz Bernhard (dir.), Histoire des Juifs en France, Toulouse, Edouard Privat, 1972.

- Boucard Daniel, Dictionnaire illustré et anthologie des métiers, Paris, Jean-Cyrille Godefroy, 2008.

- Bulletin des soies et des soieries de Lyon : 3 janvier 1903 ; 6 février 1904.

- Chaumont Jean-Philippe et Lévy Monique (dir.), Dictionnaire biographique des rabbins et autres ministres du culte israélite. France et Algérie du Grand Sanhédrin (1807) à la loi de Séparation (1905), Paris, Berg International Editeurs, 2007.

- Cointet Michèle et Cointet Jean-Paul (dir.), Dictionnaire historique de la France sous l’Occupation, Paris, Tallandier, 2000.

- Deschaumes Edmond, Pour bien voir Paris. Guide parisien pittoresque et pratique, Paris, Maurice Dreyfous, 1889.

- Le Figaro. Supplément littéraire du dimanche : 16 janvier 1886.

- Gaston-Breton Tristan, Galeries Lafayette, la légende d’un siècle, Paris, ClioMedia, 1997.

- Journal Officiel : 8 avril 1915 ; 21 mars 1917 ; 7 avril 1917.

- Klarsfeld Serge, Le mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France, Paris, Beate et Serge Klarsfeld, 1978.

- Klarsfeld Serge, Le calendrier de la persécution des juifs en France, 1940-1944, 2 tomes, Paris, Fayard, 2001.

- Le Matin : 29 novembre 1904 ; 26 avril 1915 ; 17 mars 1932.

- Peschanski Denis, La France des camps. L’internement, 1938-1946, Paris, Gallimard, 2002.

- Poznanski Renée, Les juifs en France pendant la Seconde guerre mondiale, Paris, Hachette, 1994.

- Roth François, Alsace-Lorraine. Histoire d’un « pays perdu ». De 1870 à nos jours, Nancy,

- Editions Place Stanislas, 2010.

- Le Temps : 29 mars 1903 ; 8 octobre 1916.

- Tourrand Jean-François, Sayago Doris, Bursztyn Marcel et Drummond José Augusto (dir.), L’Amazonie, un demi-siècle après la colonisation, Versailles, Quae, 2010.

- L’univers israélite. Journal des principes conservateurs du judaïsme, vol. 26, Paris 1871.

Annexes

Encounter with Philippe Bouvard

In February 2018 at the age of 89 (as he was born in 1929) the journalist Philippe Bouvard agreed to reply to a few brief questions concerning his adoptive grandparents, Fanny and Sigismond Luzzato. Despite the time elapsed, which had erased most of his memories, some remained well fixed in his mind. He also talked about his half-sisters, Claudette and Anne Marie Clémentine. The former is deceased, and the latter, unfortunately, is ill and has lost much of her memory.

Q : Mr. Bouvard, what are your earliest memories of your adoptive grandparents, Fanny and Sigismond ?

A : They were good people. Sigismond was a men’s tailor, as was my adoptive father Jules. One of their customers was the sultan of Morocco. Sigismond worked from his flat at n° 53 rue du Faubourg Montmartre; Fanny, was a housewife. They were normal people, well-balanced and very bound up with the family. I also remember that they were very nice to me. I was a truly bad pupil at that time! As for their life before the war, I cannot say; they never talked to me about it.

Q : The Luzzatos were arrested a first time in 1942. Do you remember that?

A : Those events are too far in the past for me to be able to recall them. Nor do I have any memory of their deportation in 1944; I was only 14 years old. My adoptive father was also arrested in 1942, because he was making civilian clothing for German deserters. He remained in prison for about two weeks and was freed thanks to the intervention of a friend of my mother’s, Si Kaddour Benghabrit, the director of the Muslim Institute of the Great Mosque of Paris. I still remember that in the 1940’s my mother and I often hid to escape being arrested by the Gestapo. Fanny and Sigismond had never wished to hide, as they were already elderly and ill.

Chronology

| Fanny’s life | The events and the persecution of the Jews of France |

| June 1, 1873: birth of Sigismond Luzzato (1873-1944) in Vienna, Austria December 17, 1882:Fanny’s birth (1882-1944) at Dambach-la-Ville in Alsace 1886: Sigismond’s father, Henri Luzzato, opened his tailor’s shop for men in Paris October 15, 1903: Fanny moved to live with her her mother’s family in Paris November 23 ,1904: Fanny’s marriage to Sigismond Luzato; Fanny became a French citizen April 30, 1907: Jules Luzato (1907-1974), Fanny’s only child, was born in Paris February 3, 1915: Fanny was investigated by the Paris Police Prefecture January 29, 1918: Sigismond was made a quartermaster corporal at Salonica |

1866: there were 90,000 Jews living in metropolitan France May 10, 1871: Treaty of Frankfurt; Alsace and northern Lorraine were ceded to Prussia 1886: publication of the anti-Semitic pamphlet La France Juive by Edouard Drumont |

[1] It is important to remember that in the Treaty of Frankfurt of May 10, 1871 France ceded Alsace and part of Lorraine to Prussia. Therefore, Fanny, who was born 11 years after the annexation, was a German citizen; she obtained French citizenship only in 1904 after her marriage. For the history of Alsace and Lorraine between 1870 and 1945, see: Roth François, Alsace-Lorraine. Histoire d’un « pays perdu ». De 1870 à nos jours, Nancy, Editions Place Stanislas, 2010.

[2] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Birth registry 1882, 4 E 83/23, n. 80. On the birth certificate there is a note written in the margin on March 4, 1949 by the registrar of the Civil Status Office: “died on August 15, 1944 at Auschwitz, Poland and transcribed at the town hall of Paris’s 9th district. Notice of the Ministry for the Veterans and Victims of War, dated Paris, June 13, 1946″.

[3] Base Cassini-EHESS.

[4] Among the Jewish notables from Dambach-la-Ville is the founder of the Galeries Lafayette, Théophile Bader, who was born in 1864 : Gaston-Breton Tristan, Galeries Lafayette, la légende d’un siècle, Paris, ClioMedia, 1997, p. 18.

[5] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Death registry 1870, 4 E 83/20, n. 68. On Seligmann Weil: L’univers israélite. Journal des principes conservateurs du judaïsme, vol. 26, Paris 1871, pp. 315-316 ; Chaumont Jean-Philippe et Lévy Monique (dir.), Dictionnaire biographique des rabbins et autres ministres du culte israélite. France et Algérie du Grand Sanhédrin (1807) à la loi de Séparation (1905), Paris, Berg International Editeurs, 2007, p. 757.

[6] Chaumont et Lévy (dir.), Dictionnaire biographique des rabbins…, op. cit., p. 757.

[7] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Birth registry 1846, 4 E 83/6, n. 105.

[8] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Décès, 10D 287, n. 5072.

[9] AMS, Marriage certificate of Henri Weil and Clémentine Schill, 27 février 1882.

[10] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Birth registry 1884, 4 E 83/29, n. 13.

[11] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Death registry 1885, 4 E 83/32, n. 57.

[12] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Birth registry 1886, 4 E 83/29, n. 20.

[13] On the websites geni.com and geneanet.org a genealogical tree of the Weil family, put together by several of the family descendants, can be consulted.

[14] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville : Census of 1885, 294 D/B 82, n. 72.

[15] Base Cassini-EHESS

[16] AMS, The family Weil’s official residence card

[17] Idem.

[18] It would appear, however, that Fanny’s father did not move with his wife and children to Paris. He presumably stayed in Sarreguemines to take care of his commercial activity.

[19] Several members of Fanny’s family died at this address, notably her mother Clémentine, on November 28, 1904: ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Death, November 29, 10D 287, n. 5072; her grandfather Joseph died on February 3, 1909: ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Death February 3, 10D 314, n. 595; her maternal aunt Hélène died in March 1932 : Le Matin, 17 mars 1932, p. 2. Nanette and her son Armand died, however, in Montmorency, Hélène on October 6, 1916: ANé, Supplements to the bequeath by the widow of Louis Schill to Mme Luzzato, 7 octobre 1948-15 juillet 1949, p. 3. Armand died on August 12, 1922 : ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, transcription du 12 aout 1922, 10D 398, n. 4621.

[20] He had been working at this activity at least since 1896: Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, 1896, p. 2853.

[21] Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, 1886, p. 1081.

[22] Serre Agnés T., La question urbaine en Amazonie au tournant du 2e millénaire, dans Tourrand Jean-François, Sayago Doris, Bursztyn Marcel et Drummond José Augusto (dir.), L’Amazonie, un demi-siècle après la colonisation, Versailles, Quae, 2010, p. 257-268, p. 257.

[23] Le Figaro. Supplément littéraire du dimanche, 16 janvier 1886, p. 11.

[24] Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, 1886, p. 1081.

[25] ANé, Testate of Mr. and Mrs. Luzzato, 28 septembre 1949, p. 3.

[26] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Décès, 28 mars 1904, 10D 278, n. 1447. His body was taken to the Gare de l’Est (East Railway Station) on March 30, 1903 and subsequently transferred for burial in the Frauenberg cemetery near Sarreguemines : Le Temps, 29 mars 1903, p. 3.

[27] Bulletin des soies et des soieries de Lyon, 6 février 1904, p. 6.

[28] AMS, the family Weil’s official residence card

[29] Boucard Daniel, Dictionnaire illustré et anthologie des métiers, Paris, Jean-Cyrille Godefroy, 2008, p. 125.

[30] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, 21 décembre 1888, V4E 6252, n. 1547.

[31] AN, Sigismond Luzzato’s naturalization dossier, 20 décembre 1903, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02.

[32] AN, Diverse information about Sigismond Luzzato, 2 mai 1919, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02 ; ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, 11 juin 1926, 9D 143, n. 722.

[33] There is no certainty about the date of Henri’s arrival in France, as the pertinent documents contradict each other. According to Sigismond’s naturalization file he lived in France from 1876 : AN, Diverse information about Sigismond Luzzato, 2 mai 1919, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02. On the contrary, according to the dossier on the Aryanization of the holiday house “Les Mésanges” in Montmorency, it appears that Sigismond moved to France with his parents when he was one year old in 1874: AN, Report by the provisional administrator Georges Retif on the property of Simon Luzzato-Personality of the owner, 21 octobre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[34] Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, 1886, p. 516. The Aryanization dossier for the Luzzatos’ holiday house reveals that Henri was an established tailor in 1885; his activity, however, is not listed in the Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce de 1885.

[35] Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, 1907, p. 546. Henri’s commercial activity changed addresses several times. Consulting the Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce for the period 1885-1907, excepting the years 1889 and 1902-1906, which are missing, it is learned that he first settled at n° 29 rue du Faubourg Montmartre between 1886 and 1888 or 1889; later he moved to n° 21 rue du Faubourg Montmartre, and he finally resided permanently at n°53 from 1901 to 1907.

[36] The 9th district, lying in the western part of the capital, was considered a bourgeois neighborhood in the first half of the 20th century, inhabited by well-to-do Jews, as opposed to the neighborhoods in eastern Paris, populated by less affluent Jews: Azéma Jean-Pierre et Bédarida François (dir.), La France des années noires. Tome 2 : de l’Occupation à la libération, Paris, Seuil/Points-Histoire, 2000, pp. 131-132.

[37] Deschaumes Edmond, Pour bien voir Paris. Guide parisien pittoresque et pratique, Paris, Maurice Dreyfous, 1889, p. 213.

[38] AN, Sigismond Luzzato’s naturalization request, 29 avril 1903, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02.

[39] ANé, Marriage contract between Mr. M. Luzzato and Miss Weil, 23 novembre 1903, 19042311 CM, p. 3. The business was set up with a total capital of 85,000 francs : 60,000 francs were put in by Henri, and 25,000 francs by his son : Bulletin des soies et des soieries de Lyon, 3 janvier 1903, p. 6.

[40] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Mariages, 24 novembre 1904, 10M 278, n. 1578.

[41] AMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Décès, 29 novembre 1904, 10D 287, n. 5072.

[42] Born in 1880 and married to Isidore Goldenberg between 1903 and 1904 : AN, Sigismond Luzzato’s naturalization request, 29 avril 1903, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02. Hélène Luzzato survived the war; in 1946, at the age of 66, officially residing in Paris at n° 12 rue Caumartin and exercising the profession of ladies’ tailor, she testified to having known Fanny and her son Jules: AONACVG, Declaration before the Justice of the Peace, Clément Charpentier, on May 7, 1946, dossier 5.776.

[43] Born toward 1872, she lived with her husband, Jean Kraselchick, in the 9th district of Paris: AN Sigismond Luzzato’s naturalization request, 29 avril 1903, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02.

[44] ADM, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, 29 novembre 1904, 10D 287, n. 5072. Her funeral took place the next day, Wednesday the 29th, at 2:30 p.m. at the home of the deceased. Her body was taken on November 30th to the Gare de l’Est (Eastern Railway Station) and no doubt then on to be buried in Sarreguemines: Le Matin, 29 novembre 1904, p. 2.

[45] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Births, 30 avril 1907, 9N 153, n. 503.

[46] ADMP, Analytical Directory of the Trade Register, 2163W 22, n. 32.012, p. 92.

[47] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, 3 février 1909, 10D 314, n. 595.

[48] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, 23 janvier 1910, 10D 320, n. 383.

[49] The couple survived the Second World War. Hélène died in Paris on October 17, 1979; Louis Joseph also died in Paris, in 1955. In 1946 Louis testified to having known Fanny and Jules: AONACVG, Declaration before the Justice of the Peace, Clément Charpentier, 7 mai 1946, dossier 5.776.

[50] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Marriages, 4 avril 1904, 10M 327, n. 415.

[51] It must be recalled that during the war the French government voted several laws to prevent a massive integration of foreigners. The law of April 7, 1915 provided for the revision of the citizenship of former subjects of enemy powers: Journal Officiel, 8 avril 1915, p. 1948; two years later the law of March 18, 1917 made the acquisition of French citizenship by foreign women married to French citizens conditional on government decision : Journal Officiel, 21 mars 1917, p. 2256.

[52] Furthermore, on April 7, 1917 a government decree added to these controls the obligation for all foreigners residing in France to be in possession of an I.D. card: Peschanski Denis, La France des camps. L’internement, 1938-1946, Paris, Gallimard, 2002, pp. 74-75 ; Journal Officiel, 7 avril 1917, p. 2726.

[53] AN, Central Bureau for Foreigners’ I.D. Cards, letter from the Police Prefecture to the Minister of the Interior (Bureau of General Security), 10 mars 1915, 19940505/170. It is stated that no file on this enquiry had been preserved in the Police Prefecture’s archives.

[54] Of the 190,000 Jewish men in France and Algeria, 46,000 were mobilized during World War I: Blumenkranz Bernhard (dir.), Histoire des Juifs en France, Toulouse, Edouard Privat, 1972, p. 373. Azema and Bedarida noted that “what stood out in these generally affluent and cultivated milieus was pride in being French. The memory of the war of 1914-1918 was particularly vivid, not only because it had been the opportunity for the Jews to participate fervently in the sacred union and shed their blood for the fatherland, but also because it temporarily lessened anti-Semitism. There ensued for the veterans a legitimate feeling of pride, which was to produce a deceptive sense of security”: Azéma et Bédarida (dir.), La France des années noires…, op. cit., p. 131. This phenomenon no doubt affected Sigismond and his family, who were among the French Jews involved in the war.

[55] AN, Diverse information about Sigismond Luzzato, 2 mai 1919, BB/11/4119, extrait 2862X02 ; AN, Report by the provisional administrator, Georges Retif, on Simon Luzzato’s property — the personality of the owner, 21 octobre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[56] The funeral was held on Tuesday, April 27, 1915 at the Montparnasse cemetery: Le Matin, 26 avril 1915, p. 2.

[57] ANé, Supplementary material to the bequeath by the widow of Louis Schill to Mme. Luzzato, 7 octobre 1948-15 juillet 1949, p. 3. She was buried in the Montparnasse cemetery : Le Temps, 8 octobre 1916, p. 3.

[58] ANé, Supplementary material to the bequeath by the widow of Louis Schill to Mme Luzzato, 7 octobre 1948-15 juillet 1949, pp. 10-11.

[59] ANé, Official request for the deed to the property, 15 juillet 1949, p. 2.

[60] ANé, Testate of M. and Mme Luzzato, 28 septembre 1949, p. 2.

[61] ADMP, Census of the population of Paris in 1926, D2M8 245, pp. 320-321.

[62] Idem.

[63] ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Deaths, 11 juin 1926, 9D 143, n. 722.

[64] Born in 1873, Mme Knecht was single: ADMP, Census of the population of Paris in 1926, D2M8 245, pp. 320-321 ; ADMP, Census of the Paris population in 1931, D2M8 329, p. 307.

[65] Born in 1908, Mme Thibault came from the Maine-et-Loire department : ADMP, Census of the Paris population in 1936, D2M8 578, p. 289.

[66] ANé, Supplements to the bequeath by the widow of Louis Schill to Mme Luzzato, 7 octobre 1948-15 juillet 1949, p. 4.

[67] ADBR, Dambach-la-Ville, Civil Status, Birth registry 1886, 4 E 83/29, n. 20.

[68] ANé, Supplements to the bequeath by the widow of Louis Schill to Mme Luzzato,7 octobre 1948-15 juillet 1949, p. 2.

[69] Idem, p. 8.

[70] The ceremony at the town hall was preceded by a declaration of marriage before the notary Jacques Robineau, on March 1, 1939 : ADMP, Etat civil de Paris, Actes d’état civil, Marriages, 3 mars 1939, 9M 351, n. 167r.

[71] ANé, Legal affidavit after the death of M. and Mme Sigismond Luzzato, 16 octobre 1947, p. 2.

[72] Aïssaoui Mohammed, L’étoile jaune et le croissant, Paris, Gallimard, 2012, p. 67.

[73] ANé, Legal affidavit after the death of M. and Mme Sigismond Luzzato, 16 octobre 1947, p. 3.

[74] 35 to 40% of the volunteer enlistments in the armed forces between 1939 and 1940 are stated to have been Jewish: Poznanski Renée, Les juifs en France pendant la Seconde guerre mondiale, Paris, Hachette, 1994, p. 41.

[75] AN, Report by the provisional administrator, Georges Retif, on Simon Luzzato’s property – personality of the owner, 21 octobre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[76] Aïssaoui, L’étoile jaune…, op. cit., p. 67.

[77] AN, Note by the inspector, 27 mai 1941, AJ38/1 811, dossier 32192.

[78] Registered with the Registry of Commerce since 21 juin 1921 : ADMP, Analytical Directory of the Trade Register, D33U3 268, n. 43.816, p. 158, on May 28, 1941 Sigismond was struck off : AN, Trade Register – Declaration of supplementary entry, 28 mai 1941, AJ38/1 811, dossier 32192.

[79] AN, Report concerning Luzzato Simon, 17 juin 1942, AJ38/1 811, dossier 32192.

[80] AN, Appointment of a provisional administrator, 21 octobre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[81] AN, Letter from Georges Retif to the CGQJ, 20 novembre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[82] AN, Letter from the CGQJ to Georges Retif, 2 décembre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[83] “Sir, I have the honor of reporting that Monsieur Luzzato has remitted the sum of 800 francs, as fixed by you for payment of my fees in this matter, which is hereby closed”: AN, Letter from Georges Retif to the CGQJ, 10 décembre 1941, AJ38/3 223, dossier 22595.

[84] AN, Appointment of a provisional administrator, 4 mai 1942, AJ38/1 811, dossier 32192.

[85] AN, Decision concerning payment of provisional administrative fees for management of a loss-making business or one whose available resources cannot cover these charges, 15 février 1944, AJ38/1 811, dossier 32192.

[86] Peschanski, La France des camps…, op. cit., p. 349.

[87] AONACVG, Request for acknowledgement of status as a deportee/political prisoner, 3 mai 1957, p. 3, dossier 5777.

[88] During her captivity Fanny lost her brother Seligmann, who died on September 30, 1942 at Ahun in the Creuse department : ANé, Supplements to the bequeath of the widow of Louis Schill to Mme Luzzato, 7 octobre 1948-15 juillet 1949, p. 8.

[89] AONACVG, Surveillance sheet, Luzzato Fanny Marthe, 29 mai 1957, dossier 5776. There is no trace in the Archives of the Val-de-Marne Department, where that prison’s archives are kept. The registries from the Occupation years have mostly burned; Fanny’s name is not mentioned in the General Repertories of persons imprisoned at Fresnes: ADVM, 2742W 108-112, in the section German Authorities, Correctional Facilities: list of men and women: ADVM, 2742W 101 and in the section on Individual Files of Released Prisoners 1940-1950, 1960, 1970, 1980 : ADVM, 511W 1-350.

[90] Aïssaoui Mohammed, L’étoile jaune…, op. cit.

[91] The research into Jules’ imprisonment, comprising the systematic examination of the alphabetized lists of 1942, came up with nothing. : ADMP, 1807W 3, 4, & 5 as well as the Section spéciale : ADMP, 1807W 137 and the records of those arrested by the Gestapo in the spring of 1942.

[92] Aïssaoui, L’étoile jaune…, op. cit., p. 68.

[93] Ibidem, p. 67.

[94] Ibidem, p. 68.

[95] On June 13, 1946 Fanny’s death certificate was honored with the mention “died for France”: AONACVG, Death certificate of Fanny Marthe Luzzato, née Weil, 13 juin 1946, dossier 5776.

[96] Azéma et Bédarida (dir.), La France des années noires…, op. cit., p. 147.

[97] AONACVG, Surveillance sheet, Luzzato Fanny Marthe, 29 mai 1957, dossier 5776 ; AONACVG, Request for acknowledgement of status as a deportee/political prisoner, 3 mai 1957, p. 3, dossier 5777.

[98] MS, Drancy registry, Luzzato, F9-5713.

[99] Overall, nearly 76,000 Jews (among whom 50,000 foreigners, 8000 naturalized citizens, and 8000 born to foreign parents) were deported from France between the spring of 1942 and the summer of 1944. Note that in 1941 the Jewish population in metropolitan France numbered around 320,000 individuals: Peschanski, La France des camps…, op. cit., p. 348. Sur le convoi 77 : Klarsfeld, Serge, Le mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France, Paris, Beate et Serge Klarsfeld, 1978, s. n. p.

[100] ANé, Testate of Monsieur and Madame Luzzato, 16 octobre 1947, p. 3.

[101] AN, Letter from Jules Luzzato to the Ministry of Finance, Bureau of Restitution of the Property of the Victims of the Laws and Measures of Expropriation, décembre 1942, AJ38/1 811, dossier 32192.

[102] ADMP, Analytical Directory for the Trade Register, 2163W 22, n. 32.012, p. 91.

Français

Français Polski

Polski