Marcelle KLEIMANN

We are 9th grade students from the Blés d’Or secondary school, in Bailly-Romainvilliers in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. Together with our French and History teachers, we decided to take part in the Convoy 77 project. We wanted to fulfil our duty of remembrance by trying to pay tribute to a number of people who were deported on this convoy.

We opted for a mix of fictional autobiography and explanatory narrative to rekindle the lives of these lost people, who we chose as a class. Our attention was initially drawn to Myriam Kleimann, because she was our age during the Second World War, but we then noticed that she had been deported together with her mother, Marcelle, so Maëlle and Lyli-Rose took on the task of retracing Marcelle’s life as well.

To compile the biography, we used sources such as documents provided by the Convoy 77 association and in the archives, together with videos on the Shoah Memorial website, on the Yad Vashem website and on a website dedicated to children deported from the Lyon area. The autobiographies of Ginette Kolinka, Henri Borlant, Simone Veil and Ida Grinspan were also very helpful. We also watched interviews with Marceline Loridan and Yvette Lévy.

My name is Marcelle Podorowsky and I was born on November 2, 1905 in the 11th district of Paris. My father’s name was Bernard Podorowsky and my mother was Esther Walinski.

I married Moses Kleimann. He was a Russian who, after the First World War, during which he had been imprisoned by the Germans in the Mailly camp in the department of Aube, stayed on in France. We got married in 1924. I had my first child, my wonderful son, Bernard Kleimann, in 1925, which was a marvellous event.

Then, in 1928, my little girl, Myriam, was born.

We lived a comfortable life: we lived in the 10th district of Paris, where we had a ready-to-wear store. My husband was a dressmaker, and I was in charge of a several seamstresses. This suited me perfectly and I was very happy.

My children were doing well in school and were thriving. I needed nothing more in life than to love my husband and see my children happy. We did not lead a deeply religious life and we experienced no anti-Semitism in Paris, although we heard about what was happening to the Jews in Germany.

In 1939, when France went to war with Germany, we took to the roads as part of the Exodus and ended up in the Creuse department of France. A few months later, we decided to go back to Paris. We returned to our apartment and my husband and I went back to work.

However, in July 1941, tragedy struck. Moïse was arrested during a round-up near the Place de la Bourse. I decided to stay on in Paris for a while with Bernard and Myriam. I managed to arrange to have my husband hospitalized, which bought us some time. Sadly, however, he was deported to Eastern Europe on July 29, 1942, on convoy 12, although I only found this out some time later.

In the meantime, my store had been taken over by a non-Jewish person. I was no longer allowed to work or own property due to the anti-Semitic policies of the Vichy government. Bernard then left Paris to go to stay with some of our family who lived in Marseille. Since the spring, we had also had to wear a Jewish star. How humiliating!

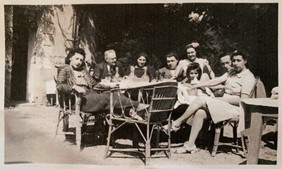

On July 16, 1942, in order to escape the race-related laws, and because we had been warned that a major round-up was about to take place, I decided that my daughter and I also needed to escape. However, we had to get across the demarcation line! We stowed away in a locomotive and ended up in Marseille, where we stayed until the Germans arrived in October, at which time they occupied the whole of France. Since we no longer felt safe where we were, we headed for Lyon, but then decided to take refuge in Orgelet, in the Jura mountains. We stayed with a local shopkeeper, Mr. Philippe Cottet, who my family and I had known since 1934. Before the war, we had often sent the children to stay with him on vacation while my husband and I were working.

Soon after we arrived, my son made contact with Pierre Verney, the leader of the local Resistance group in Orgelet. As a result, we began to help the Resistance movement. This was very important to me and Myriam also joined in. It was the natural thing to do and we were not afraid. After the war, Mr. Verney stated: “Mrs. Kleimann, her daughter Myriam and her son Bernard helped me both with communications and by helping the recusants*, whom they kept hidden and fed. They also camouflaged weapons from parachute drops in their homes.

*Translator’s note: men who refused to participate in the STO, or Compulsory Work Service.

As a result of police investigations and searches in the area, the Prefect of the Jura issued a decree on August 24, 1943, ordering our family to leave Orgelet and go to stay in Les Bouchoux, in the Haut Jura. My son Bernard knew of some isolated farms there.

All three of us refused to submit to this, and after having spent about two months there, Bernard, my eldest son, fled to Lyon in order to be available to his regional Resistance leader, Commandant Georges Jouneau, who was then head of the 4th bureau of the A.S. in the Rhône-Alpes region. We went into hiding in farms in the Haut Jura.

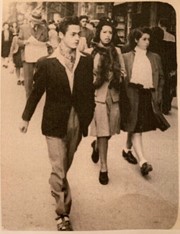

In January 1944, we finally went to stay with Bernard, who was going back and forth between the Jura and Lyon. We missed him so much. He was staying at the home of a woman who lived at 16 cours de la République in Villeurbanne, in the suburbs of Lyon, and we moved in with him. We used the name Kleber as an alias. Bernard was making fake ID cards and seals in one of the rooms. Myriam and I helped him in his mission as liaison officer by delivering envelopes that he was unable to deliver himself.

Unfortunately, on March 24, 1944, some plain clothes officers came to the apartment where we were staying and asked for my son. When they realized he was not there, they waited for him all afternoon, which made us very anxious. Of course, when Bernard arrived at the end of the day, they arrested him. I never heard from him again. I knew that the police might come back for us too, so I decided to take my daughter and go into hiding with some other people in Caluire, another suburb of Lyon.

These facts are confirmed by witnesses’ testimonies and also by Resistance reports about the Kleimann family.

Myriam and I left the apartment and spent the night at a friend’s house, then we headed for Grésieux to go to stay with my sister, Mrs. Bernier, who had kindly agreed to take us in. I hadn’t seen her for a long time, since the beginning of the whole sorry story and I was happy to see her again.

We lived in a part of her house. We stayed there, undercover, until June 27, 1944, the day on which we were arrested in the Place de la Charité in Lyon. We had delivered a parcel to a friend in the Resistance and were just leaving the Red Cross center. Klaus Barbie and two officers were waiting for us.

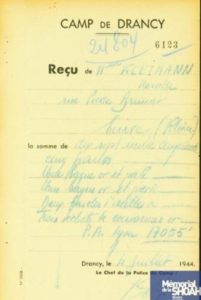

We were detained for four days in the Fort de Montluc. On July 1, we were transferred to Drancy. My daughter and I knew absolutely nothing about what would happen next. We just thought that we would have to work, nothing more, like everyone else in Drancy.

A month later, on July 31, we were deported. We headed East, not knowing where we going or that we were to live in such horror for the next few months. When it was our turn to be deported, Myriam, I and other Jews had to pack our bags. We were not allowed to take very much and had to pack quickly. I had arrived with some cash and jewelry that I was unable to reclaim.

We left Drancy by bus at about four o’clock in the morning. We were taken to the Bobigny railroad station, where 60 of us, along with our bags, were crammed into a cattle car. Everyone struggled to get the place seat near the only little window. We didn’t know how long the trip would last. There was just one tin bucket in the car for us to relieve ourselves.

What troubled us all most was the fact that we didn’t know where we were going or how long the journey would take. We were very hungry and thirsty and there was so little space. Myriam was scared and so was I, but as her mother I had to console her because people were dying in the car. We traveled for three days with scarcely anything to eat. I still have terrible memories of those wagons.

When we arrived at Auschwitz, we were roughly unloaded from the cattle cars to the sound of men shouting and dogs barking. There were Red Cross trucks for the weakest people, but Myriam and I decided to walk the mile or two, which left us exhausted. A disconcerting smell, like something burning, stung our noses, but we didn’t pay much attention to it. We heard people shouting and screaming. The women and children were moved to one side and the men to the other. Myriam and I were told to stay together in the group on the left and we guessed that the other group of women with children was not going to the same place. The guards took us to some sheds where we had to take a shower and then we were shaved. We had to get undressed in front of everyone, which I found really embarrassing because I had never had to take my clothes off in front of other people. After that, a woman tattooed me with a number, which from then on would become my identity.

I had to put on some old clothes that had been worn by people who had died. I found out that the people who had got on the trucks had been taken to the gas chambers and the odor we could smell was of their bodies being burned.

I think it was from that moment on that I became traumatized. The image of that camp will remain in my memory forever.

During those few months in Auschwitz, people died every day. I even lost friends. Personal hygiene was almost non-existent, since there were communal latrines and washbasins, which we could only use at certain times of the day.

We were all very thin and we worked very hard. We had to dig trenches for example, and carry heavy loads. The only food we had was a bowl of soup to share between five of us, so we were very hungry. We ate everything, even the tiny crumbs of bread from the floor. We all became dangerously ill.

In Auschwitz, it was important not to show fear and we had to remain calm even when faced with violence, meaning that we must not cry or scream when we were beaten. Some people were even beaten to death and all we could do was stand there and watch without a word, which was just abhorrent. Unfortunately, if you survived, as I did, you felt guilty: we felt that we should have died like the others.

In October, Myriam and I were deported to Kratzau in Czechoslovakia, where we worked much harder in a munitions factory. It was cold and snowy, and I did everything I could to get Myriam into the factory because officially she was too young to work there, but I couldn’t leave her outside scraping the snow and mud.

Photo of the Kratzau camp

One morning, May 9, 1945, we woke up to find that there were no guards: they had run away as the Red Army was approaching and left us behind. We realized that we were free and decided to leave the camp with a few friends. We managed to survive for a while in the surrounding villages, then took a train to Prague, where we walked to the American zone, which meant that we could be repatriated France.

On May 22 we arrived back in Paris. We went to the Lutétia Hotel, where we met with an aunt and an uncle. I was told that my husband, Moïse, had died in Auschwitz in 1942 and that Bernard had been killed during interrogation. You can’t imagine how distressing this was, and even as I write this, I am still grieving. I was not even able to say goodbye to them or to comfort them, but they are forever in my heart, my beloved son and my dear husband.

We managed to get back our apartment and the workshop, albeit with difficulty, from the person who had taken possession of them. I restarted my business, this time with Myriam, who began work as a cutter.

I found love again in 1954 and got remarried to a man called Nathan Piper. He was also a widower and his wife had been another Marcelle.

I applied to have myself and my children recognised as having been in the Resistance, but initially only Bernard was granted this status, posthumously, with the rank of sergeant. I had to keep battling away because at first, I was only recognized as having been deported on racial grounds, and I did not want to be identified only by my religion. Some years later, I finally received my Resistance fighter card, of which I am very proud.

Sources

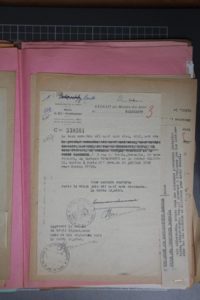

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77

- Testimonials of Myriam Baumerder, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, which are available on the Shoah Memorial website.

- The website dedicated to children deported from the Lyon area

- Short biographies on the Yad Vashem website

- Books by Simone Veil, Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah ; Ginette Kolinka, Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant, Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan, J’ai pas pleuré

Français

Français Polski

Polski