Marco ADATO

Contributors

Between 2020 and 2024, numerous students have participated in the Les Passeurs de Memoire (“Passers-on of Memories”) cross disciplinary (History/Literature) workshop at the Voltaire secondary school in the 11th district of Paris. Their work has involved analyzing archived records and contributing to the biographies of a number people who were deported on Convoy 77 and who lived in the 11th district during the Second World War. The students who took part in this project now live in this very same neighborhood.

The students of the Les Passeurs de Mémoire workshop wrote this biography together with Elsie Epstein and Alma Laborey.

From Turkey to Paris

Mordo Adato, who later used the name Marco, came into the world on December 13, 1901, in Kierklisse[1], in the Ottoman Empire. He was almost certainly the youngest of five brothers: Aron, who was born in 1884, Victor, who was born in 1886[2], Chapat and Yomtov, whose dates of birth we do not know.

HIs parents, Nessim Adato (1859-1934) and Mazalto Eskenazi (1859-1944) were merchants in Constantinople.

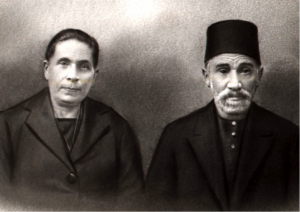

Nessim and Mazalto[3]

Nessim and Mazalto were members of the Ottoman Empire’s large Jewish community, the vast majority of whom were descended from Jews who had migrated to the empire from 1492 onwards. They were Sephardic Jews who Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile had driven out of Spain and Portugal, and who still spoke Ladino or Judeo-Spanish.

Known as Djudios [4], many Judeo-Spaniards [5] from Greece and Turkey emigrated to France over a period of around fifty years, from 1890 to the mid-1930s. The majority of families and young Djudios from Turkey settled in France between the end of the First World War and the early 1930s. Shortly before the Second World War, there were some 35,000 Judeo-Spaniards in France.

In the heart of the 11th district of Paris, in the Popincourt neighborhood (from rue Sedaine to place Voltaire, including rue de la Roquette, rue Basfroi and Popincourt), there is an area that used be called “Little Turkey” or “Little Istanbul”, where many “Oriental Jews”[6] lived and worked. In 1936, there were 2,600 of them living in the Roquette neighborhood, which was a quarter of the total foreign population.

The majority of these immigrants came from low-income backgrounds, and usually moved to the neighborhood to be near other family members who were already living there. Marco was no doubt one of them.

Mordo/Marko probably migrated to France in the early 1920s. He most likely changed his name to the French version, Marko/Marco when he arrived in Marseille, on the south coast of France. His older brother Victor was already living there, having arrived in 1910[7]. By 1919, he was living at 8 rue Popincourt in Paris. Marco may have moved in with his brother that year, but we have no information about this. Victor was a tailor, and when they got married in 1920, according the marriage certificate, his wife Rachel was also a tailor, although she later became a dressmaker.

Between the wars: settling in and integrating into French society

The next record we found on Marco dates from 1923. On March 24 that year, Marco Adato married Louise Cohen (sometimes known as Lucie) at the town hall in the 11th district of Paris. Louise Cohen was born in Constantinople in 1901. Her parents, Haïm Cohen and Esther Cohen, were shopkeepers who lived at 39 rue Popincourt. Their daughter, who lived with the, was a dressmaker.

As for Marco, he lived at 3 rue Pétion and was a sales representative.

Their witnesses were Menahem Jacob, a retailer who lived at 65 rue Sedaine, and Jacques Gabay, a salaried employee who lived on rue de Belfort in the Roquette neighborhood. They were all members of the Oriental Jewish community. The following day, March 25, 1923, they had a religious wedding ceremony at the Tournelles synagogue[8].

After the wedding, the couple moved to 8 rue Popincourt.

Marco then worked as a travelling salesman and Louise as a dressmaker.

They were among the Jewish migrants, mainly from Eastern Europe or Turkey, who lived in the east of Paris and worked in the poorest jobs (street hawkers, market traders, second-hand goods dealers, ragpickers, tailors, dressmakers, knitters etc.). Louise probably worked “to order” at home.

A family photo: from left to right, Marco and his wife Louise Cohen, his older brother and his wife Rachel Acco and their two children, Isidore, the oldest boy and Léon, his little brother. The photo must have been taken in 1924 or 1925. @SimonLouvet

Between 1925 and 1937, the family grew larger.

Marco and Louise had five children, all of whom were born in Paris: Victor, who was born on April 30, 1925, Sisso (also called Risso), born October 4, 1931, Henri, born October 9, 1933, Mathilde, born May 14, 1935 and Suzanne, born May 18, 1937. They were all born at the Rothschild hospital[ 9] on rue Santerre, in the 12th district of Paris. This was a maternity hospital that provided free medical care to people on low incomes, in particular Jewish migrants from the east of Paris.

While the children were French nationals because they were born in France, there is no record of the parents ever having applied to be naturalized as French citizens. Marco’s older brother, Victor, on the other hand, was naturalized in 1936. Marco was probably not earning enough to pay the naturalization fee. This was quite common among low-income families.

In common with other migrant groups, the Judeo-Spaniards managed between them to provide for their physical and spiritual well-being. They were thus able to maintain their traditional lifestyle and culture, and to meet socially.

They shopped at places like the Middle Eastern grocery store “Aux cinq continents” (The five continents) on rue de la Roquette, which filled the air with the scent of oriental spices.

Cafés were also popular meeting places:

- The “Café Bosphore” (the Bosphorus) café-restaurant at 74 rue Sedaine, where people met to play cards, welcome new arrivals and give them tips about life in France.

- Nearer to the Adato’s apartment was the “Chez Behar” café at 17, rue Popincourt[10], which served Turkish coffee in an Oriental-style setting.

We found no evidence that Marco belonged to any local self-help organizations or sports clubs, even though there were plenty of them in the area.

In 1913, the first synagogue for Judeo-Spaniards, Al Syete, was founded at 7, rue Popincourt. It was designed to meet the needs of the rapidly-growing immigrant population, who had no place to worship other than a little oratory in the back room of the Café Bosphore. As it was just a stone’s throw from where they lived (firstly at 8 rue Popincourt, from 1923 to the early ‘30s, and then at 3 impasse Popincourt, where they were living at the time of the 1936 census), they no doubt went to Al Syete at no. 7 regularly.

They must also have spent time with Uncle Victor, Aunt Rachel and their older cousins, Isidore and Léon, who lived on the same street.

The children went to local schools, which were non-religious and taught republican values, so this no doubt helped the family to integrate into French society. They first went to the nursery school at 8 rue Popincourt, opposite the synagogue. After that, the boys would have gone to the boys’ school on rue Froment, and the girls to the one on rue Bréguet.

When the war broke out, Victor was 14, Risso was 8, Henri was 6, Mathilde was 4 and Suzanne was barely 2.

The Occupation, France under the Vichy regime and the first signs of discrimination

The war brought with it an increasingly bleak atmosphere. Cousin Isidore was called up. In the neighborhood, people enlisted voluntarily show how loyal they felt towards France.

However, when Germany beat France occupied the country, and with the arrival of the Vichy government, things soon changed.

Starting in summer 1940, the Vichy government put in place an anti-Semitic policy in collaboration with the Nazis.

On September 27, 1940, the Germans instructed all Jews in the occupied zone to register themselves as part of a census. Marco, like many other Judeo-Spaniards, went to the local police department in the 11th district to register, because he felt he ought to comply with the law. All French and foreign Jews were supposed to register between October 3 and 20, 1940. the Seine department, the names were listed in what was known as the Fichier Tulard (the Tulard file).

On October 3, 1940, the Vichy government issued the first decree on the “status of the Jews”, which forbade them from working in a number of professions[11].

On April 26, 1941, a German order extended the ban to cover the entire commercial sector. This meant that Marco, a street vendor, was no longer allowed to operate his business. He therefore found himself out of work.

The second “status of the Jews” decree, enacted on June 2, 1941, banned Jews from entering various public spaces.

While some of the Jews in the Seine department fled elsewhere, others, including the Adato family, had no choice but to stay on in Paris.

Day-to-day life with five children must have been tough. Everyone had to fend for themselves as best they could in order to survive.

Caught in a trap for the first time

The roundups in the occupied zone began in 1941. The first was the “green ticket” roundup, which took place on May 14 and mainly targeted Polish and Czech Jews and stateless people[12].

On August 20, 1941, 2,400 French police officers, acting on orders from the occupying forces, carried out another roundup of Jews in Paris. Known as the “XI° roundup” (11th district roundup) this time it targeted Jews of all nationalities, including the Spanish-Jewish population in the Roquette district.

The 11th district was cordoned off at 5:30 a.m., and the subway stations were closed. The Gestapo ordered the French police to arrest all “Israelites” (Jews) aged between 18 and 50[13.] Marco was arrested on August 20, 1941, either in the morning, at home, because he was listed in the Tulard file, which was made available to the police, or on the street during an identity check, when he would have been carrying his identity card with the word “Jew” stamped on it. 3,000 men were arrested in the 11th district that day. Eyewitness accounts, such as Albert Cohen’s[14] describe how rumors about the arrests soon began to spread, and how the police went to a few cafés in the neighborhood to warn the local residents.

On August 21, Marco was taken by bus from Place Voltaire to Drancy internment camp[15]. When they arrived, the French police checked them in. The Paris Police Department ran the camp, which held up to 4,232 people aged between 18 and 50 in an unfinished low-cost housing estate known as the “Cité de la Muette”[16].

Marco was interned in Drancy until December 1941. His wife was probably allowed to visit him there.

Then, between December 2 and 6, 1941, when living conditions and health standards had become abysmal, a German medical commission released almost 1,000 internees, including some of the youngest and most seriously ill.

Marco Adato was one of them. He was released on December 4, 1941 because he was suffering from oedema and cachexia (emaciation and general fatigue due to serious illness or malnutrition).

Surviving from day to day

When he was released, Marco managed to find a job that Jews were legally allowed to do. He went to work for the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews), a Jewish organization that the Vichy government founded in November 1941.

The work was legal, and the salary reasonable. Marco was given a “legitimization card”, valid until September 9, 1942, that said “the holder must not be troubled on grounds that he is a Jew, and will remain exempt from any internment measures. This provision extends to any family members living with him”. Marco appears to have worked at the UGIF center on rue Lamarck, in the 18th district of Paris.

However, this job did not mean that workers could not be arrested.

In 1942, discriminatory legislation against the Jews extended again. They were obliged to wear a yellow star in public places and subject to a curfew. Children were still allowed to go to school as normal, however.

Danger loomed ever closer

During the summer of 1942, Marco’s uncle Victor, aunt Rachel and cousin Léon (whose French citizenship had been revoked in September 1941) were arrested at their home at 8 rue Popincourt as part of the Vel d’Hiv roundup. They were interned in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz (Leon on Convoy 21, Rachel on Convoy 23 and Victor on Convoy 32), where they were all murdered. Isidore, their eldest son, and his wife Simone took refuge in Toulouse, in the Haute-Garonne department of France. They both joined the Resistance movement and survived the war, as did their daughters, who were kept hidden in a Catholic convent in the Aveyron department[17].

Marco and his family were not arrested that summer. They may, due to the increasing number of arrests and the general sense of fear, have gone into hiding, or moved to another location. It is worth noting that the Drancy records show Marco’s address as number 4, rather than 3 impasse Popincourt.

The Nazi occupiers and French police continued to arrest people…

In the first half of 1944, a third of the Judeo-Spanish Jews were arrested, compared with a fifth of Jews of other nationalities. The hunt seemed to be gathering pace.

The noose tightened further on May 5, 1944, when some forty Judeo-Spaniards were arrested at the Bosphore café at 74 rue Sedaine.

The pressure continued to increase. In the days that followed, on May 6, 11 and 13, further targeted roundups took place ( in particular of the people who lived at 10 and 12 rue Popincourt).

Two months later, on the evening of July 6, 1944, according to two witnesses, the French police arrested Marco in an officially licensed Jewish café, Chez Behar (later renamed l’Istanbul), at 17 rue Popincourt. He was taken to the 11th district police department, along with eight other customers who were in the café at the time, at around 9pm. The police register lists the reason for Marco’s arrest as “Jewish”. All of the others were arrested on the same grounds.

The following day, at around 3:30 p.m., Marco was transferred to Drancy, where he was interned together with the other customers from the Chez Behar café: Seid Abdoulah, Josué Assa, Léon Braunstein, Nissim Levy, Menahem Pinto, Michel Policar, Nahama Sadicaris and Yedidia Tchiton, all of whom were originally from Constantinople or Thessaloniki.

Marco was interned in Drancy for three weeks. He was deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp on Convoy 77, which left on July 31, 1944. He was murdered in the gas chambers soon after he arrived, as were the other men arrested at the café, just a few days before Paris was liberated. His official date of death was later declared to be August 5, 1944.

He was one of 5,300 Spanish-Jewish men, women and children from France that the Germans and the Vichy regime police arrested, deported and exterminated.

After the war: Louise Cohen’s struggle to have Marco officially recognized as having been a political deportee

Soon after the war ended, Louise, Marco’s wife, began the procedure to have his status recognized.

On January 16, 1948, she filed a missing person’s report for her husband Marco Adato, who had “died in the camps”.

On May 7, 1948, she was naturalized as a French citizen and continued to fight for recognition of her husband’s status as a deportee.

On March 9, 1951, a court pronounced Marco Adato officially dead. The judgement was then transcribed into the civil registry at the 11th district town hall.

On January 20, 1954 he was granted the status of political refugee.

On August, 1968, Louise applied for a death or deportation certificate in the name of Mr. Marco Adato Marco. As the legal beneficiary of a political deportee, she was then granted 12,000 francs in compensation.

Victor and Marco both died in Auschwitz.

The rest of Victor and Marco’s brothers, Aron, Yomtov and Chapat, survived: one emigrated to the United States, while two remained in Turkey.

Memorials to the Judeo-Spanish deportees

Commemorations and historical research have only recently helped to shed light on the little-known fate of the Judeo-Spanish community.

On March 24, 2003, the well-known French Auschwitz survivor, “Simone Veil, unveiled a slab at Auschwitz to commemorate the deportation and extermination of the Judeo-Spaniards in Birkenau. The inscription is written in “djudezmo”[18].

In 2019, the Muestros Dezaparesidos nonprofit organization published a commemorative book on the history of this little-known Jewish community from the former Ottoman Empire: Le Mémorial des Judéo-Espagnols déportés de France (Memorial to the Spanish Jews deported from France) [19]. Their research enabled them to draw up a list of the 5,300 Judeo-Spanish people who were deported from France.

Notes and References

[1] The Marmara region of Turkey

[2] Victor was the father of Isidore, whose story Simon Louvet recounted in an illustrated novel entitled “ISIDORE ET SIMONE, JUIFS EN RESISTANCE” (“ISIDORE AND SIMONE, JEWS IN THE RESISTANCE”), published by Ouest France in 2023. His research on the Adato family is available in French on his blog https://isidore-juif-au-maquis.fr/

[3] Photo @simonLouvet.

[4] Judeo-Spaniards

[5] or Sephardic

[6] also known as “Levantine Jews” or ‘Sephardic Jews’

[7] He spent time in Barcelona during the First World War in order to avoid being sent to the camps for foreigners, and returned to France in 1919. See Simon Louvet’s blog page in French on Victor et Rachel

[8] Mentioned in the newspaper L’Univers Israélite

[9] After being used as a military hospital during the First World War, it reverted in 1918 to its original use as a hospital for Jewish patients.

[10] A photo of the café “l’Istanbul”, which was renamed as such after the war

[11] The civil service, the armed forces, journalism, publishing, the theater, the cinema, all medical and legal professions.

[12] 3700 men between 18 and 40 were arrested and detained at the Japy gymnasium in the 11th district.

[13] Supplement to the magazine Kaminando, Y Avlando 42, April-June 2022, “L’histoire de Lisette Cohen Abouth” (The story of Lisette Cohen Abouth) page 27.

[14] idem, page 27

[15] The first internees arriving in Drancy

[16] 3000 were from the 11th district and 1500 were French citizens. Source “Muestros Dezaparecidos” page 140.

[17] “ISIDORE ET SIMONE, JUIFS EN RESISTANCE” (“ISIDORE AND SIMONE, JEWS IN THE RESISTANCE”), published by Ouest France in 2023. His research on the Adato family is available in French on his blog https://isidore-juif-au-maquis.fr/

[18] Judeo-Spanish

[19] Mémorial des Judéo-Espagnols déportés de France (Memorial to the Spanish Jews deported from France) published by Muestros Dezaparesidos, Paris, 2019

Français

Français Polski

Polski