Marie-Anne Florica VEXLER

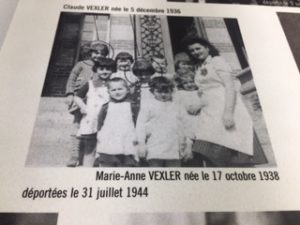

Marie-Anne and her elder sister Claude-Renée, with a group of children and their supervisor, Denise Holstein, taken on the steps of the villa in Louveciennes.

A family like any other…

Marie-Anne Florica, born October 17, 1938 and her elder sister Claude-Renée, born December 6, 1936 in Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin, a town in the Seine-et-Marne department in north-central France, were the daughters of Dr. Iancu Vexler, born July 29, 1907 in Husi, Romania, and Fajer Vexler, née Elbaum, born on January 23, 1906 in Warsaw, Poland.

The couple had lived at 14, rue de la Ferté-sous-Jouarre since 1936.

After graduating from medical school, Iancu opened a general practitioner’s surgery in Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin.

The couple had four daughters. Claude-Renée, born in 1936, Marie-Anne Florica, born in 1938, Hélène-Sarah, born in 1940 and Jeanne-Marie, born in 1941.

During the war, Iancu volunteered as a soldier and joined the 4th Infantry Platoon on June 9, 1940. After the armistice, he returned to Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin, where he once again worked as a doctor.

Despite the anti-Semitic laws that had been introduced in France, in particular the decree of October 7, 1940, which excluded all Jewish hospital doctors from practicing medicine, and the decrees of June 2 and June 24, 1941, which limited the number of Jewish doctors practicing per department, Dr. Vexler continued to practice in the town.

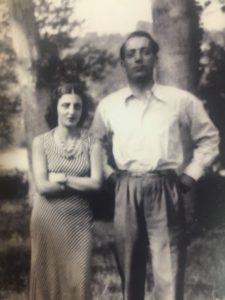

Iancu and Fajga Vexler,

Photograph taken from the book “Les Vexler : une famille juive déchirée par la guerre”

(The Vexlers: a Jewish family torn apart by war).

The arrest

On October 21, 1942, French gendarmes, led by Marshal Bonnet[1], went to the family home and arrested the couple.

On that date, 81 foreign Jews were arrested in a major roundup in the Seine-et-Marne department. They were sent to Drancy internment camp and then deported to Auschwitz on November 6, 1942 on Convoy N° 42.

The couple’s youngest two children, Hélène-Sarah, born in 1940, and Jeanne-Marie, born in 1941, were entrusted to Lucien Clément and his wife, who were friends of the couple. There they remained hidden in La Croix-Verte, a hamlet near Bassevelle, in Seine-et-Marne. In 1943, they went to live with their maternal grandmother in Bussières[2], also in Seine-et-Marne, where they continued to live in hiding until the liberation.

Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne went to stay with their nanny at her home in a hamlet, the Hameau de Mauroy, near Doue in Seine-et-Marne.

Arrival at Auschwitz

On November 11, as soon as Fajga arrived in Auschwitz, she was taken to the gas chambers and killed. She was only 36 years old. Iancu was selected to work as a Sonderkommando and was given the number 74154. On June 2, 1943, he was assigned to the Birkenau hospital to work alongside Dr. Josef Mengele, “the angel of death”[3] where he became the doctor for the gypsies. He was liberated in May 1945 by Soviet troops[4].

The fate of the elder daughters, Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne Florica

At the time of their parents’ arrest, Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne Florica were staying with a nanny, Mrs. Cauturon, in Mauroy[5], a hamlet near Doue, a few miles from Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin.

However, as of September 1943, despite the nanny’s misgivings, they were entrusted to the UGIF, Union Générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews[6]). After passing through a sorting center for Jewish children, UGIF center N° 28, on rue Lamark in Paris, they were sent to center N° 59 in Louveciennes[7], in the western suburbs of Paris.

There they stayed for a year, in difficult circumstances. There was not enough food, a lack of care and a shortage of clothes, but not a lack of love. The two girls were cared for by Denise Holstein[8], a 17-year-old teenager, who was in charge of 9 younger children. Marie was a “wonderful, sparkling little girl” with “big blue eyes and black hair”, according to Denise[9].

The living conditions were terrible and Pierrette Grisel, a social worker and member of the Red Cross, wanted to extricate them from the center[10]. She was a member of the OSE, Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants, or Children’s Relief Organization[11], a clandestine group run by resistance fighters who had infiltrated the UGIF. This plan never saw the light of day, however, and on July 22, 1944, all of the children in the center, 34 children and 5 monitors, were taken away and then deported. Only three returned from Auschwitz.

Between July 20 and 22, eight UGIF homes were targeted during a series of roundups organized by Aloïs Brunner[12]. More than 345 children between the ages of 1 and 15, from children’s centers all over the Paris region, were arrested and transferred to the Drancy camp.

Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz on July 31, on the last convoy, Convoy 77. It was a very long way. According to Denise Holstein’s account[13], the journey took two and a half days. The two Vexler sisters were put in the same cattle car as the other children from Louveciennes, and the conditions were terrible: “There was no shortage of provisions, but of water, yes, there was. We were unable to swallow anything: we were all so thirsty. The children were crying, so we had to comfort them”.

The two girls were gassed as soon as they arrived, on August 2, 1944. Claude-Renée was 7 years and 8 months old and Marie-Anne Florica was 5 years and 2 months.

Drawing by Cassioppée Perraguin, a 12th grade student

Two lives cut short, two brief lives.

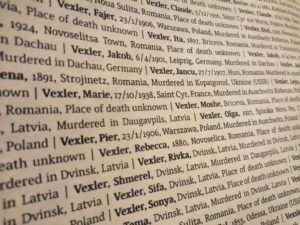

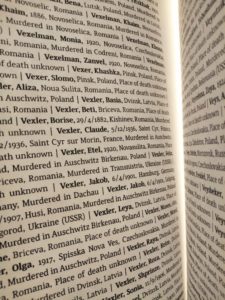

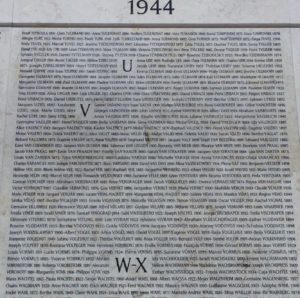

Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne Florica were thus assassinated by the Nazis because they were born Jewish. They were not given time to live their lives. Their names are on the commemorative plaques of the Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin War Memorial, the book of names at the Auschwitz-Birkenau National Museum and on the wall of names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

School trip to the National Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau on November 28, 2019

The Shoah Memorial, January 21, 2020.

Looking at a photo of the two girls with Denise Holstein, taken in Louveciennes.

The return to everyday life, and the quest for recognition….

Iancu Vexler returned to Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin to resume his work. There he was reunited with his two young daughters, Hélène-Sarah and Jeanne-Marie.

In 1952 he remarried Aimée Barreau, with whom he had two more children, Catherine, born in 1951 and François-Ruben, born in 1957.

However, this return to everyday life also involved a long struggle with French authorities to have the crime committed against his wife Fajga and his two eldest daughters, Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne, recognized.

On May 1, 1959, Iancu Vexler sent a letter to the Minister of Veterans and War Victims to request death certificates for his two daughters. He also wanted the words “Mort pour la France”, meaning “Died for France” to be included on the death certificates. The Minister of Veterans Affairs then sent a letter to the Prefect of Seine-et-Marne on June 23, 1959 to ask for information on the two girls. On July 18, 1959, the Prefect replied in great detail about the circumstances of the arrest and disappearance of Iancu Vexler’s two daughters. The prefect noted that “the facts are well known in the region and that the arrest of the members of this family is unquestionably attributed to their religious origins”[14].

At around the same time, Dr. Vexler received a letter on June 23, 1959 from the Ministry of Veterans Affairs regarding his request for the death certificates and the words “Died for France” for his daughters. The Ministry informed him that it could not grant his request because it had no information on the date and place of the girls’ deaths. It would only be able to only issue missing persons’ certificates after an investigation had been carried out.

Dr. Vexler thus continued the battle. On July 3, 1960, he applied to the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War asking for Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne to be recognized as “non-returnees”. On the form issued by the Ministry of Veterans and War Victims, it was noted that this was an application for “race-related deportees”, and that in this case the two girls had been arrested by an emissary of the Union of French Jews (acting on behalf of the Germans). It was not until April 22, 1961, that the mayor of Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin certified that Claude-Renée and Marie-Anne had not returned to Dr. Vexler’s home since the end of the war.

On April 26, 1961, the Department of Veterans and Victims of War sent Dr. Vexler two forms to apply for missing person’s certificates. He returned them on April 27, 1961 and received the documents on May 1, 1961, thus two years after his initial request. This enabled him to obtain a judgment pronouncing the girls’ deaths. Without this, the Minister of Veterans Affairs could not grant his request for the words “Mort pour la France”, meaning “Died for France ” to be written on their death certificates.

Once he had the missing persons’ certificates for the two girls, Dr. Vexler was able to refer the case to the Court of First Instance in order to obtain a judicial declaration of the death of his two daughters. He obtained a copy of the death certificate from the civil registry of the municipality of Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin on September 6, 1961.

On July 5, 1962, Dr. Vexler, who had been acknowledged as a political deportee, was naturalized as a French citizen[15].

He then continued his struggle to have his wife and daughters awarded the distinction “Died for France”. On April 26, 1979, he wrote a letter to the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War, or more specifically the Directorate of Statutes and Medical Services, to which he sent the girls’ birth certificates, on which the declarations of their deaths were noted. He also enclosed the girls’ French nationality certificates. Claude-Renée had become French citizen according to Article 3 of the law of August 10, 1927, a declaration having been registered at the Ministry of Justice on December 8, 1938. Her sister had also become a French citizen according to a similar declaration registered at the Court of First Instance in Coulommiers on April 7, 1939.

The Department of Veterans Affairs wrote a letter to the mayor of Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin on July 11, 1979, in order to obtain a recent copy of the two judgments declaring the death of the two young girls. On July 17, 1979, the mayor sent copies of Claude-Renée’s and Marie-Anne Vexler’s birth certificates, mentioning that they had died in Poland on July 31, 1944, although this was in fact the date on which Convoy 77 left Bobigny station for Auschwitz.

On January 4, 1980 the mayor of Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin received notification from the Secretary of State for Veterans that he could write the words “Died for France” on the Vexler girls’ death certificates.

Thus, after many long years of effort, Dr. Vexler finally succeeded in having the words “Died for France” appear on the civil status records of his wife and daughters, who were murdered at Auschwitz.

Iancu Vexler died on June 12 1990, at the age of 83.

The War Memorial at Saint-Cyr-sur-Morin.

This is a dreadful story. A family’s life was shattered, simply because they were Jewish. Two children lived through horrific experiences, “guilty” only of having been born Jewish, in what is known as “the land of human rights”.

Arrests by the French gendarmerie, deportations from Drancy and mass murders, all carried out with no regard for nationality, gender or age.

And this long, very long struggle of a relentless father to restore the identities of his children, to name them, and to gain recognition for them in the town where they were born. All so that we never forget, that we shall never forget them, his daughters.

[1] Source Ajpn Anonymes, Justes et persécutés durant la période nazie. Research carried out by Fréderic Viey, historian.

[2] Letter from the Prefect, dated July 23, 1959.

[3] Source Ajpn Anonymes, Justes et persécutés durant la période nazie. Research carried out by Fréderic Viey, historian. Dr. Vexler wrote an article about his daily life with the gypsies in Auschwitz-Birkenau: “J’étais médecin des Tsiganes à Auschwitz “, published in 1973 in the Monde Gitan, 1973 n°27 p. 1 à 10

[4] Les Vexler: une famille juive déchirée par la guerre. Editions Terroirs

[5] Not Mrs. Couturon, as mentioned in the Prefect’s letter dated June 23, 1959. Information found in a letter from the Union Générale des Israélites de France dated November 12, 1944.

Source : Les Vexler : une famille juive déchirée par la guerre. Editions Terroirs, 2012.

[6] The General Union of the Israelites of France was created, at the instigation of the Germans, by a law of the Vichy government dated November 29, 1941. The organization represented Jews and was responsible for social welfare; it paid allowances to households deprived of income and financed canteens and hospices. After the round-ups in the summer of 1942, it opened centers for Jewish children in Paris and the suburbs. There were UGIF homes on rue Lamarck, rue Vauquelin, rue des Rosiers, and in Louveciennes, La Varenne, Montreuil, Neuilly, Saint-Mandé.

[7] In Louveciennes, there existed a UGIF center where thirty-nine Jewish children were housed in an orphanage created in 1880 by Jules Beer. Following the round-ups initiated by Aloïs Brunner, the head of the Drancy camp, the Gestapo arrested all the children who had taken refuge in Louveciennes, together with their monitors, on July 22, 1944. There, one month before the Liberation, thirty-four children and five monitors were rounded up and taken to Drancy before being deported on the last large convoy to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. SK (Editor) note: Denise Holstein recalls that there were two centers in Louveciennes: a large center, through which Charlotte Schuhmann and her friend also named Charlotte spent some time, and a smaller center, on the steps of which the children’s picture was taken. Denise remembers the children from the second home well, but says that these days that the first one was too big for her to remember.

[8] Denise Holstein was then a teenager, born in 1927. She arrived at the Louveciennes center in 1943. She was arrested on July 22, 1944 and deported by the last convoy to Auschwitz. She is one of the few survivors from this Jewish children’s center.

[9] “Je ne vous oublierai jamais, mes enfants d’Auschwitz”, Denise Holstein.

[10] Witness statement of Pierrette Grisel, taken by Ms. Gudelette, French National Archives, on June 20, 1946.

[11] The OSE was a Jewish organization created on October 28, 1912 to help children and provide medical assistance to persecuted Jews.

[12] Alois Brunner was a Nazi war criminal born on April 8, 1912 in Rohrbrunn, Austria. He took over the management of Drancy camp on July 2, 1943. In one year, he had more than 22,000 French Jews or Jews residing in France deported, i.e. 1/3 of all the Jews deported from France.

[13] Testimonial of Denise Holstein, published in 1992. Article in the newspaper Libération, April 20, 1999.

[14] Letter from the Prefect of Seine-et-Marne dated July 18, 1959 to the Minister of Veterans and Victims of War concerning Dr. Vexler, Stateless and holder of a “Privileged Resident” card.

[15] Les Vexler : une famille juive déchirée par la guerre. Editions Terroirs, 2012.

Image library

Français

Français Polski

Polski