Max DOMBLATT (1918-1964)

Portrait photo of Max Domblatt

Source: file on Max Domblatt © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-876-11

Max Domblatt was born into a Polish family that migrated to France early in the 20th century. Before the First World War, from 1908 to 1914, many young people from Poland left their homeland each year to work from April to October on farms, in industry and in armaments factories. The workers were housed in barracks and temporary camps in poor conditions, and were usually paid very low wages.

It is estimated that around 10,000 Polish people traveled to France each year to carry out this seasonal work. We believe that Max’s parents Jean and Léa Domblatt, may have been among them, and that they decided to settle in France permanently after the war. This may also reflect the rural exodus that occurred as a result of industrialization in France, which caused a shortage of labor in rural areas, where there were too few people left to carry out agricultural work on farms, particularly in the Limousin region. This phenomenon was further exacerbated by the poor state of the economy in general, political repression in Poland and the fact that some of the Polish population was subject to Russian or Austrian domination. Between 1890 and 1939, an estimated 387,000 people moved from Poland to France.

Biography of Max Domblatt

Max Domblatt came into the world on June 22, 1918 in Limoges, in the Haute-Vienne department of France. His parents, both of whom were Jewish and born in Poland, were Jean Domblatt, a tailor, and Léa Domblatt, née Rozenswerg, who was a housewife. Max, who was the last of their five children, had four older sisters: Sophie (Zlata in Polish), Sarah (Sola), Paulette (Faïga) and Rose.

Photo of Jean and (we suppose)] Léa Domblatt on the family grave at the Bagneux cemetery in Paris (our own photo)

Photo of Max’s father, Jean Domblatt

Source: File on Jean Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-63-5-875-13

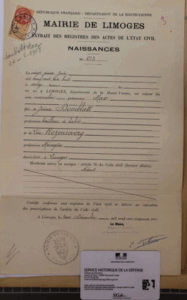

Max Domblatt’s birth certificate

Source: File on Max Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-876-19

Max spent most of his childhood in Paris. The family lived in an apartment building at 24 rue Pradier in the 19th district of the city, but we were unable to find any further information about this period of his life. The only thing we found, which was on the French National Library website, Gallica, is a small ad that he placed in the French newspaper Les Echos on November 28, 1933. Max Domblatt, aged 16 at the time, was looking for a job in a fabric factory. He described himself as reliable. He later went on to follow in his father’s footsteps and became a tailor.

In 1938, Max began his military service and became a private in the 65th French Infantry Regiment. He was mobilized on January 9, 1939, shortly before the start of the Second World War, due to rising international friction, and served until March 27, 1940, when he was demobilized and returned home.

After that, he appears to have lived at 49 rue Custine, in the 18th district of Paris.

However, this address is only listed on one US Army repatriation record, which was issued when he was liberated from the Dachau concentration camp on May 20, 1945. We therefore assume that he was living there before he was rounded up. When he returned from the camps, he moved back in with his parents, so the address on most of the records is 24 rue Pradier, in the 19th district of Paris.

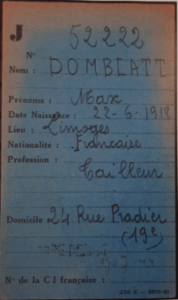

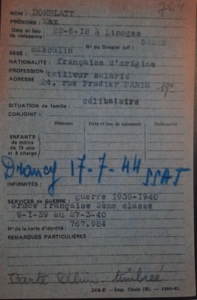

We also found two identity cards from the Paris Prefecture, dated 1940 and 1941. The Vichy government required Jews to register themselves officially with their local prefecture. Max did as the government said.

The declaration that Max Domblatt made in the prefecture in 1940

Source: File on Max Domblatt, Prefecture file, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5638_040579_L

The declaration that Max Domblatt made in the prefecture in 1941

Source: File on Max Domblatt, Prefecture file, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5609_005648_L

According to a record from the Combat district Police Station, in the 19th district of Paris, dating from 1952, Max was arrested on July 14, 1944 during a dance class, which was being held near Boulevard de Strasbourg in the 10th district, not far from Passage Brady. The report states that Max was arrested by a group of civilians from the French militia, two of whom he recognized. Jews were forbidden from many activities at the time, including taking dance classes, going to the movies, swimming in public swimming pools and even walking in parks and town squares. That means that if he was in the dance class, he could not have been wearing the obligatory yellow star, which in itself was grounds for immediate arrest. However, we have no further evidence for this, and more importantly, the records are inconsistent: several others state that he was arrested at his parents’ apartment at 24 rue Pradier.

We visited the 10th district and discovered that the address given in the police report was near the former Lévitan furniture store, which was converted into an annex of Drancy camp in 1943. Between July 1943 and August 1944, hundreds of Jews were interned in the store and worked at taking in, sorting, cleaning, repairing, packing and dispatching furniture and other items looted from Jewish families’ apartments.

It therefore remains unclear where Max was arrested.

The following day, the French militia arrested his parents, Jean and Léa, at their home.

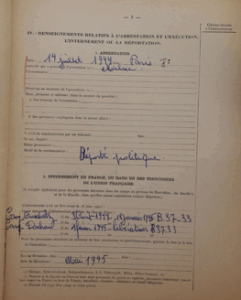

Report on Max’s Domblatt’s arrest

Source: File on Max Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21-P-635-876-4

After he was arrested, Max was handed over to Commissioner Permilleux’s Jewish Affairs division, which was responsible for tracking down and arresting thousands of Jews in Paris. The following day, he was taken to the Police Headquarters Depot 1, where he arrived at 3:15 a.m. His parents arrived at the same time. Might they have been held together in a detention or interrogation center before being transferred to the depot, which was the last stop before Drancy? In any case, all three members of the Domblatt family left the depot at 3 p.m. and were taken to Drancy.

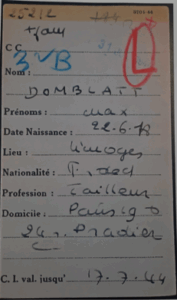

Max was then interned in Drancy transit camp from July 17 to 31, 1944. He was first assigned to room 4 on staircase 18, and then moved to room 4 on staircase 3. His Drancy registration number was 25212.

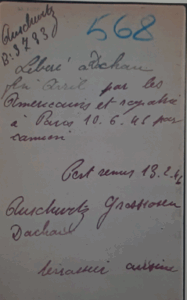

The letter B, written in blue, meant that the prisoners could be deported immediately. The letter L was added at a later date, as it refers to the fact that Jean had been liberated from the camps.

Max Domblatt’s Drancy record (front)

Source: File on Max Domblatt, Drancy file, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5688_125369_L

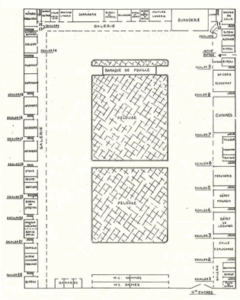

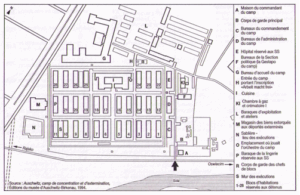

Plan of the ground floor of Drancy camp

Source : www.memoire-viretuelle.fr

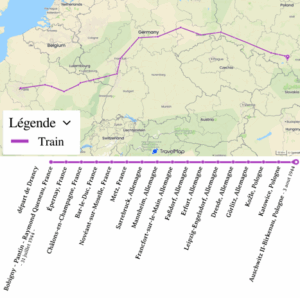

Max was then deported on Convoy 77, which left from Bobigny station on July 31, 1944 and arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944. He was taken on foot to the Bobigny station by Aloïs Brunner and his men, who later burned the Drancy camp archives to destroy the evidence. However, two internees managed to save the file containing the names of all the people who had been held prisoner there. The 1,500 people who were still left in Drancy were liberated by the Resistance on August 18, 1944.

In order to gain a better understanding of what Max went through, we turned to survivors’ testimonies, even though, clearly, everyone’s experience was unique, so their memories are deeply personal. According to survivors Jean-Louis Henrion, Régine Skorka-Jacubert and Denise Holstein, the traveling conditions on Convoy 77 were appalling. The deportees were loaded into cattle cars. There were 1306 deportees in total on the train, with around 60 people crammed into each car. There was only one bucket by way of a toilet, and a few straw mattresses on the floor. As for provisions, there was a little bread but almost no water, even though the heat was stifling at that time of year. What made matters even worse was that there were only a few very small openings for ventilation. The journey took three days and nights, and many people died along the way. Some people also tried to escape during the journey, but were soon met with gunfire.

Convoy 77 was planned and organized by Aloïs Brunner, an SS officer and Nazi criminal who was born in 1912 and died between 2001 and 2010 while working for Bachar al-Assad, the then president of Syria. He was responsible for the deaths of 47,000 Austrian Jews, 43,000 Greek Jews and 25,000 French Jews. He was also responsible for organizing numerous raids on Jewish children’s homes run by the UGIF (Union Générale d’Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews). However, he was never tried for his evil deeds. In July 1943, under his supervision, the Germans took control of the Drancy camp. Most of the 1306 people aboard Convoy 77 were arrested in France in July 1944. It was the last large transport to leave France.

Map of the route taken by Convoy 77

Source: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

Convoy 77 arrived at its destination, Auschwitz-Birkenau, in the middle of the night of August 3 to 4, 1944, at around 3 a.m. As soon as the deportees climbed out of the cars, the Nazis carried out a selection: some 70% of them were sent straight to the gas chambers (mainly women, including Max’s mother Lea Domblatt, children, elderly people and pregnant women), while the remaining 30% were selected to go into the camp to work.

Max, who was a young man, was selected to work and taken to Auschwitz I, the concentration camp. The Nazis assigned him the task of peeling potatoes in the kitchen. This was an indoor job, under cover, and it also gave the prisoners the occasional opportunity to steal a little food, thus increasing their chances of survival.

Some records also reveal that he was involved in earthmoving work, such as digging trenches and pits.

Max’s registration number was B37-33, and his father Jean’s was B37-32. Given that the two numbers are consecutive, we can surmise that father and son were together during the selection and when the numbers were tattooed on their arms, and thus may well have traveled from Drancy to Auschwitz together.

To gain an insight into living conditions in the camp, we read Convoy 77 survivor Denise Holstein’s testimony. Each prisoner was tattooed with a number. She described how the “Pollacks”, who tattooed the newly-arrived deportees, would insert the needles even deeper if they complained. Every morning, the deportees were woken up at 3 a.m. with a coffee-type drink by way of breakfast. Then came the roll call, which lasted until 8 a.m., during which they had to kneel down and were not allowed to move. Max Domblatt remained in Auschwitz until January 18, 1945, a total of 5 months and 14 days.

Plan of the Auschwitz I camp

Source: Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp, published by the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum, 1994

In the summer of 1944, the Red Army launched a major offensive in Eastern Europe, which led to the liberation of the Lublin and Majdanek camps. American, British and French forces found the camps further west a few months later. Shortly after this offensive, Heinrich Himmler gave the order for all concentration camp prisoners to be transferred into Germany, by what came to be known as the “death marches”.

However, the Soviets advanced so rapidly that they were not able to evacuate all the prisoners in time. There were several reasons that the Nazis forced the prisoners to leave the camps on foot: they did not want the Soviets to find the prisoners and thus uncover their heinous crimes, and they still felt they needed the prisoners to work, in order to keep up their munitions supply.

Max was sent on a “death march” to Gross-Rosen in January 1945, when the Soviet army was only a few dozen miles away from Auschwitz. He was subsequently transferred to the Dachau concentration camp, either on foot or by train, although we have no records of this. We can assume that he traveled by train, however, as his father Jean later testified that he was transported from Gross-Rosen to Dachau on a train in which around 125 deportees were crammed into each car.

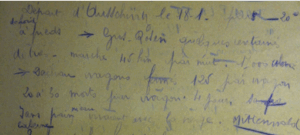

Jean Domblatt’s testimony, dated June 5, 1945

Source: file on Jean Domblatt, French National archives, ref. F9 5584

Source: Christian Grataloup, Atlas Historique Mondial (World Historical Atlas), Les Arènes –L’Histoire, 2019, page 536-537. Chapter entitled Le monde dominé par l’Occident, La libération des camps (1944-1945) The world dominated by the West (The liberation of the camps (1944-1945)).

Map on which we have drawn the route that Max took from Auschwitz to Dachau.

His father Jean followed the same route, but whether they were together, met up again or were able to share a hug, we do not know. Before they set off, the Nazis gave the men their rations, but as the marches went on, they were given nothing to for several weeks. According to survivor Jacques Zylbermine, who was 15 years old when he set off on the “death march”, they had to eat snow in order to survive. Some of them traveled by train, while others walked for 2 or 3 days from Auschwitz-Birkenau to Gross-Rosen, and then for around 5 days from Gross-Rosen to Dachau. The “death marches” took place in freezing temperatures, in grueling conditions, and many people died as a result of exhaustion, hunger and hypothermia. Others, if they refused to continue, were executed by the Nazis.

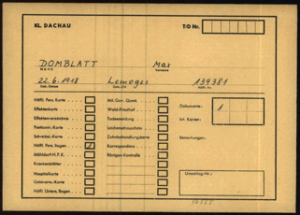

When he arrived in Dachau, Max was assigned the serial number 139381. Once again, he worked in the camp kitchens, peeling potatoes.

Max’s detention record from Dachau

Source: File on Max Domblatt, Enveloppe-DACHAU-1.1.6.2-10024077-front

The prisoners slept in wooden bunks, as they had in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Living conditions were extremely harsh, with excrement left lying everywhere, which led to widespread disease. Dr. Sigmund Rascher carried out drug experiments on some of the prisoners in the camp, and tested their resistance to diseases. Meanwhile, the SS and Gestapo tortured prisoners who broke the rules or tried to escape.

Our research on the French National Library website led us to a book in which the name “Max Domblatt” was mentioned, but there were no further details available. We then managed to obtain a digital copy of the book, and discovered that it was the testimony of a concentration camp survivor who, more importantly, he had been held in the same barracks as Max in Dachau. This man, whose testimony was a mine of information, was Charles Joyon. In 1957, he published Qu’as-tu fait de ta jeunesse? (What did you do when you were young?), in which he described his life during the Nazi occupation and his experience of deportation. It includes the following passage: “In late January, a large number of Auschwitz deportees, all Jews, were evacuated to Dachau. The countless deaths that had left huge gaps in the camp’s workforce were soon filled. My bunkmate was a young Jewish man from Marseilles by the name of Attali Israël. He was barely 16 […]. My other bunkmate, Jean-Pierre Lhemann, who was from originally from Alsace, had been living in Paris and was arrested in Normandy […] An artist, José Ortéga, from Argentina, slept underneath us […] Beside him there was a young Jew with neurasthenia, Max Domblatt, who wept and moaned non-stop. Then there was Paul Messey, an 18-year-old from the Vosges region, who clung to life for several months and finally succumbed the day after the camp was liberated […]”. We thus know who Max was with during his time in room 4 of block 17 at Dachau concentration camp. This testimony is particularly significant as it is the first record we found that relates directly to Max’s personal experience of the camps. According to Charles Joyon, Max suffered severe psychological distress as a result of what he went through. We also discovered that, at least at that time, Max and his father were not detained together.

We also drew on Charles Joyon’s testimony to describe the Dachau camp during Max’s time there. He wrote that the camp was surrounded by a reinforced concrete wall, electrified barbed wire and a deep trench. The SS patrolled the perimeter with machine guns and dogs, which made it impossible to escape. There were thirty barracks, or blocks, on either side of a central passageway, each of which housed around 50 deportees. The infirmary and equipment store were located in the first few blocks. At the far end of the central passageway was the area where the prisoners all had to assemble for roll-calls.

The prisoners had to get up at 4 a.m. every morning, had ten minutes to get washed with what little water they had, and only just had time to get dressed before they had to report to an inspector and have their names ticked off. They were given only a bowl of some sort of herbal tea and a morsel of bread before they started their day. After that, the three hundred men made their way to the assembly area. The Nazis never let the men rest; they made them march, run and jump up and down. At midday, they were given a small ration of food, often a ladleful of thin soup. In the afternoon, they continued to walk back and forth from their barracks to the assembly area, and were regularly checked for lice. If they were infected, they were beaten and washed with buckets of cold water, before being disinfected by being stripped naked. The deportees often struggled to find their own clothes in the huge piles, so were left in freezing, draughty rooms for long periods, which made them more susceptible to diseases. Every morning, the prisoners who were still alive collected the bodies of the men who had died during the night.

The Dachau records reveal that both Max and his father worked as potato peelers. We have no way of knowing if they worked side by side, but we suppose they did.

In January, temperatures dropped to -22 F (-30°C), and prisoners had their feet in the snow all day, which could lead to hypothermia. At one point, a convoy of Hungarians brought typhus into the camp. The disease spread so rapidly that prisoners were confined to barracks, but nevertheless a dozen or so men died every night.

Of the 25,000 prisoners, 15,000 died of hunger and disease over a 4-month period. There were around 300 deaths a day in Dachau. The crematoria were kept burning, but still some bodies were thrown into pits. In the last few months, anyone who the camp doctor deemed to be too weak or sick was killed.

The sheer cruelty of life in the concentration camps sometimes overwhelmed the deportees’ capacity for empathy. Some of them lashed out at anyone who made too much noise during their short rest breaks and when they were trying to sleep. The large number of fatalities each day in the various blocks resulted in empty beds and empty spaces, which in turn let in the freezing air. Sick people were moved to rest blocks for medical treatment. They were afflicted by a range of diseases, each more devastating than the last. Charles Joyon, for example, contracted meningitis, which plunged him into a coma. Each dead man was rapidly replaced by another deportee. It was during this period of new arrivals that Charles Joyon first encountered Max Domblatt.

In early April, there were rumors that the Allies were on the move and were beginning to take German towns and cities. As the Allied planes dropped their bombs, prisoners from the Buchenwald camp began arriving at Dachau.

When the camp was about to be evacuated on April 26 or 27, the sick prisoners were sorted into two groups: those who were fit enough to be transported and those who were not. Charles Joyon was put in the second group. The men who were fit to travel were assembled in the courtyard and prepared for departure. However, an unforeseen event prompted a change of plan, and the prisoners were sent back to their barracks.

On April 28, 1945, the SS once again assembled the deportees ready to evacuate them.

The Red Army liberated Auschwitz on January 27, 1945, and found around 7,000 survivors. This was followed by Gross-Rosen on February 28, and Dachau in late April and early May. However, when the camps were first discovered, the prisoners were not released immediately because the Allies were afraid that diseases such as typhus, which were rife in the camps, would spread to the outside world. Some camps were therefore placed under quarantine. Before the Nazis abandoned the camps, they burned most of the storage facilities, in which they had stored a great deal of evidence relating to their crimes. However, in the few remaining storerooms, the Soviets found some of the deportees’ belongings, such as eyeglasses, suitcases, clothing (including hundreds of thousands of men’s suits and over 800,000 women’s outfits) and even their hair (over 7 tons of human hair was found).

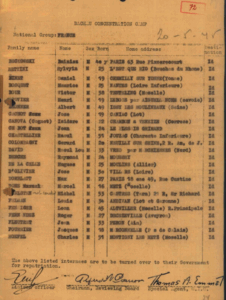

Repatriation list issued by the U.S. Army in Dachau on May 20, 1945

Source: File on Max Domblatt, © Arolsen archives –9932733_1.1.6.1-GCC-3-11folder-211a

The Dachau camp was liberated on April 29, 1945 by the 45th Infantry Division of the 7th United States Army. The deportees celebrated well into the night, happy that the hell was finally over. Max spent a few days hospitalized in a medical facility, where he was registered as patient number 0/4691. He was 5’5” tall, weighed 125 pounds, was in good physical health and was not sick. He asked to be returned to his parents’ home in Paris, so we can safely assume that he wanted to be reunited with his family as soon as possible.

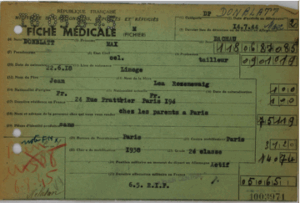

Max Domblatt’s medical report card

Source: File on Max Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen -21-P-635-876-14

On his way back to France, Max arrived at the Emmendingen transit camp in Germany on May 24, 1945. At the end of the war, this camp was used as a transit camp for Jewish deportees bound for their home countries. Living conditions were better than in the other concentration camps, but due to the large influx of deportees, there were still food shortages and a lack of resources. He left there on June 5, 1945. He was then taken by truck to Paris, where he arrived on June 10, 1945. He moved back in with his parents at 24 rue Pradier, as noted on his medical card. This was when he was reunited with his father. He also returned to his job as a tailor.

Max Domblatt’s record card from Drancy (back)

Source: File on Max Domblatt, Drancy files, adults ©Shoah Memorial / French National archives, FRAN107_F_9_5688_125369_L

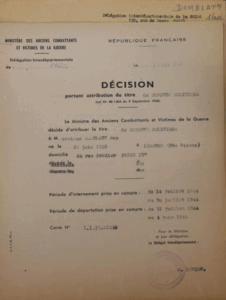

In 1953, Max was officially granted the title of “Political deportee”. This status acknowledged the suffering the deportees endured and ensured their place in history as a tribute to their resistance, courage and pain. It entitled them to certain rights and benefits, such as financial compensation, medical treatment, specialist care and, in some cases, a permanent pension for those most severely affected by the deportation. In 1954, Max received a payment of 13,200 francs from the French State.

Notification that Max had been granted “Political Deportee” status

Source: File on Max Domblatt, ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen -21-P-635-876-9

Political deportees could apply to have their names inscribed on memorials and at remembrance sites. They were also entitled to legal protection against any potential discrimination arising from their involvement in resistance movements, although this did not apply to Max Domblatt. They were also given priority in certain sectors, such as access to housing, medical care and help in returning to civilian life.

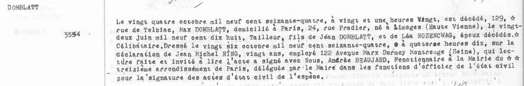

Max died at 9:20 p.m. on October 24, 1964 at 129 rue de Tolbiac in Paris. His death certificate was declared and his death certificate signed at 2.10pm on October 26 1964 by a man called Jean-Michel Ring, who was 20 years old at the time. He later became funeral planner at the Barbier & Sons Funeral Services and stone workshop at 122 avenue Marx Dormoy, in Montrouge, in the Seine department, which was across the street from the Bagneux cemetery. He also surveyed all the Jewish burial vaults in the Bagneux and Pantin cemeteries, with funding from the French Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah.

And so our story ends when Max came back from the camps. Did he ever marry? Did he ever change jobs? Did he ever give testimony about what happened to him?

During our research, we found out that Jean Michel Ring, who had known Max Domblatt when he was alive, sadly passed away on June 4, 2024. We would very much have liked to have had the opportunity to speak with him, but unfortunately this was not possible.

Max Domblatt’s death certificate, dated October 24, 1964

Source: Paris archives, Town Hall of the 13th district of Paris, Death certificate n°3554, ref. 13D 431

Max Domblatt was buried in the Bagneux cemetery in 1964. We visited the cemetery and discovered that Max is buried in a vault in row 6, in section 31, which belongs to Les Amis de la ville Szydlowiec (Friends of the town of Szydlowiec), a non-profit organization of which Max’s father Jean was a founding member in 1926, and also acted as treasurer. Max is buried alongside his father, Jean. The name of Léa Domblatt, Jean’s wife and Max’s mother, who died in Auschwitz, is inscribed on the memorial to the female victims from the town.

The Bagneux cemetery, in the southern suburbs of Paris, is one of the largest Jewish cemeteries in France, and large numbers of Jewish people are buried there. Many of them, from poor and working-class Jewish families are buried in collective vaults. Many of them, like Max Domblatt’s family, migrated to France from Eastern Europe, and made their homes in Paris. The cemetery was founded in the late 19th century in order to meet the growing demand for burial sites for the Jewish community.

The Memorial to the deportees originally from the Polish town of Szydłowiec, who died at the hands of the Nazis, in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris

(our own photo)

Photo of Max on the grave at the Bagneux cemetery in Paris

(our own photo)

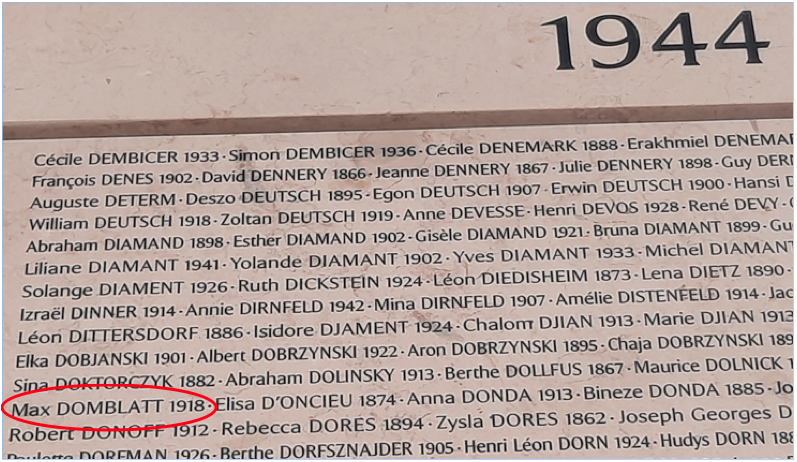

Max’s name is also inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial de Paris, beside those of his parents and the 75,565 other Jews deported from France.

Wall of Names, Shoah Memorial, Paris

(our own photo)

We would like to thank:

- The Convoy 77 team, who kindly sent us most of the records that enabled to retrace Léa Domblatt’s life story and write this biography

- The documentation department at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, for making us welcome and supplying some additional records

- The International Institute for the Memory of the Shoah at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, and the Arolsen Archives in Bad Arolsen, for taking the time to answer our questions and provide us with additional records.

- The Haute Vienne departmental archives service, the Paris archives service, the town hall of the 19th district of Paris, the staff at the Bagneux cemetery and the mayor of Desvres.

- Everyone else, from near and far, who helped us bring this project to fruition.

We would like to express our most sincere gratitude to Yvette Lévy, a Convoy 77 survivor, who very generously invited us into her home to share her story and give us a better understanding of what the Convoy 77 deportees went through. Meeting her and hearing what she had to say was an incredible opportunity that will be remembered as one of the highlights of this project.

Français

Français Polski

Polski