Myriam KLEIMANN

We, Kelly, Noémie, Aya, Ariana and Angélina, are 9th grade students from the Blés d’Or secondary school, located in Bailly-Romainvilliers in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. Together with our French and History teachers, we decided to take part in the Convoy 77 project. We wanted to do fulfil our duty of remembrance by trying to pay tribute to several people who were deported on this convoy.

We opted to write a fictional autobiography interspersed with explanatory sections in order to portray the lives of two members of the Kleimann family. We chose to do this in class since during the Second World War, Myriam, the daughter of the family, was the same age as we are now.

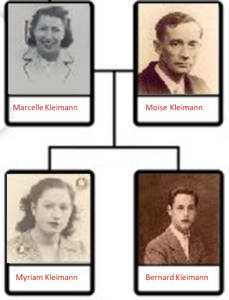

My name is Myriam Kleimann and I was born on November 21, 1928 in the 10th district of Paris. I am Jewish, a French citizen and I live at 112 rue Réaumur in the 2nd district of Paris. My father was Moise Kleimann, who was born on October 17, 1895 in Kamenets, Ukraine. He was a Russian refugee and worked in his own store, making women’s clothing. My mother, Marcelle Podorowsky , (married name Kleimann) was born on November 2, 1905 in the 11th district of Paris. I had one brother, Bernard Kleimann, who was born on March 10, 1925.

I was 11 years old when France went to war against Germany and 12 years old when the war was lost and Marshal Pétain became the leader of France. He established the Vichy regime, which was anti-Semitic and as from October 1940, gradually excluded Jews from French society.

It wasn’t easy for my family and I, being Jewish, but my parents, with whom I had a good relationship, did all they could to ensure that I was happy. I spent a lot of time with my brother. There were only three and a half years between us, so we got along pretty well, we played games together, laughed together, and sometimes our parents would spend time with us too. I thus grew up in a family environment and had a relatively happy childhood with them, despite the restrictions that the Vichy regime placed on us.

During the exodus (when the Germans occupied France and many Jews left Paris, some temporarily, some for good), we went to stay in the Creuse department, but a few weeks later we went back to Paris so that my parents could go back to work.

However, my father was arrested during one of the initial round-ups in 1941, despite the fact that he believed himself to be safe because he had been a soldier in the First World War.

We assume that his circumstances and deportation were made more complex by the fact that he was married to a French woman. He was not actually deported until July 29, 1942, on Convoy 12. We know that he spent some time in hospital before he was sent to Auschwitz, where he died at the age of 47 on November 30 of the same year.

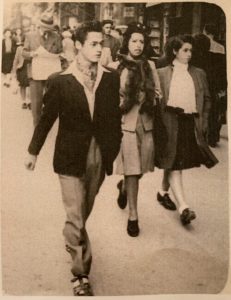

My mother decided to stay on in Paris, at least for a while, but the store had to be sold by an Aryan manager, so on July 16, 1942, having heard about the possibility of mass arrests, she decided to flee to the free zone in order to escape the racist, anti-Semitic legislation. We managed to hide as stowaways in a locomotive and went to join Bernard, who had already fled to Marseille on the south coast, where we had family. We stayed in Marseille for a while until the Germans invaded the free zone in the south of the country in November 1942. We then went to seek refuge in Lyon and then in Orgelet, in the Jura mountains. We stayed with a local shopkeeper called Philippe, whom we had known since 1934 and with whom we had previously gone on vacation. He was a member of the Resistance.

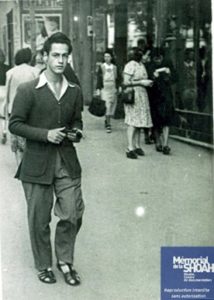

Not long after we arrived, Bernard made contact with Pierre Verney, the head of the local Resistance unit, and we became liaison and assistance agents for the rebels, who we helped to hide and feed. We also concealed weapons, which had been dropped by parachute, in our homes and often mailed or delivered letters.

As a result of investigations and searches that were carried out in the area, the Prefect of the Jura put our family under house arrest on August 24, 1943. We had to leave Orgelet and move to Brouchoux, higher up the Haut-Jura mountains. After two long months in the Haut-Jura, Bernard left to seek refuge in Lyon, where he made himself available to his Resistance leader. At that time, we were living under an assumed identity using the surname Kleber.

My mother and I, after hiding in various farms in the Jura, went to join my brother in January 1944. He was staying with a lady at 16, cours de la République, in Villeurbanne, just outside Lyon in the Rhone department, and we moved in with him. I was delighted to be with my brother again at long last. We had one room and a kitchen, in which Bernard made forged identity cards. My mother and I helped him in his mission as a liaison officer by delivering papers when he could not do it himself.

Sadly however, Bernard was arrested by the Gestapo on March 14, 1944. He was killed during an interrogation on April 21, 1944. My mother and I left our home on the very day that Bernard was arrested because we felt sure that we too would be arrested. We spent the night with a friend, Mrs. Unger, and the following day she sent us to her sister, Mrs. Bernier, who was staying in part of a house belonging to a Miss Camus, at 105 rue Pierre Prunier in Caluire-et-Cuire. We remained hidden with “my aunt” (Mrs. Bernier) until June 27, 1944, when we were arrested. We had received a message from one of Bernard’s friends, who asked for a package, but just as we were dropping it off at the Red Cross office in Place de la Charité in Lyon, we were arrested by Klaus Barbie and two German officers. They were looking for us on account of our resistance work and recognized us from photos they had of us.

I was thus arrested on June 27, 1944, at the age of 15, on grounds of my “race” and Resistance activities. We were held in the Montluc prison (between Lyon and Montpellier) for four days. During that time, my mother was interrogated and she found out that Bernard was dead. We were devastated. He was too young to have died, at only 19 years old! I was so scared! On July 1, we were transferred to Drancy camp, and then on July 31, 1944, we were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The journey was horrific. We had to get up at 4 o’clock in the morning. Everyone was silent as we waited to get on buses that took us to the Bobigny railroad station. There, we were loaded into cattle cars, sixty people at a time. People argued about who would stand near the little window. No one knew where we were going, or how long the journey would last. I was scared to death. The smell was unbearable and everyone was very thirsty. After three days and two nights, we arrived in Auschwitz in the early hours of the morning. There was a lot of yelling and screaming, and dogs were barking. I couldn’t quite believe what was happening to me.

When the doors opened, the stench was overwhelming. The weary deportees made their way to the trucks, not knowing that they were going to be taken straight to the gas chambers. My mother and I were selected to work, so we were admitted to the camp. We had to take a cold shower and then we were shaved and had our numbers tattooed on our arms. My mother and I hardly recognized each other after our heads had been shorn. We had to undress in front lots of SS men, which was not easy, and if we didn’t want to undress, they became abusive and beat us, which made me feel ashamed and humiliated. And being shaved and seeing our hair fall to the ground was absolutely atrocious.

The barrack hut where I slept was lined with wooden bunks on three levels. There were 6 of us on each level and we had to sleep head to toe. Every morning, we had to go to roll call, which took so long that we felt we would die. We often had to do chores such as collecting grass clippings and bringing them back to the camp. Food was scarce; we had very little to eat. The evening roll call was the worst thing of all, because we worked for 12 hours a day and it took an hour each morning and evening to walk to and from work. We were incredibly tired. We often also had to undergo selections, carried out by Professor Mengele. My mother would always stand behind me to make sure that she would be inspected at the same time as me.

We, the Jewish prisoners, were given only rags to wear and we had a large cross on our backs. The latrines were in a barrack hut, and the women had to relieve themselves sitting back-to-back on wooden boards. The smell was terrible, I could hardly stand it, but we had no choice but to go, and if we weren’t quick, they pushed us out.

There was no soap and we had to wash ourselves with chlorine powder. We had one loaf of bread per person, which had to last us four days, from Monday to Friday. We were constantly hungry. Sometimes the workers hid little pieces of bread under the machines, and those scraps of bread helped to keep us from starving to death.

In October there was one final selection, during which they decided which of us should be sent to the Kratzau camp in Czechoslovakia to work in a factory. Once again, we travelled in cattle cars. There was a lot of snow there, little food, and soup but no spoons to eat it with. If we got sick, we weren’t allowed time off to get better, and if we didn’t keep moving, we were beaten. But at last there was no longer the smell from the crematorium, so we were able to breathe. We were also forced to work. Every day we walked about 3 miles to the factory near the village and on the way the Czech children insulted us and threw stones at us. We had to pass a deli in the village and we often fantasized about eating sausages. At first, I and another young girl were deemed too young to work in the factory so we had to scrape away the snow and mud outside. My mother eventually managed to get us into the factory to work, where we were assigned to painting grenade tubes yellow. We worked day and night.

We were liberated on May 9, 1945: the guards had all fled because the Red Army was liberating the area. My mother and I left the camp with other women. We begged for food from nearby farms or took food from houses that had been abandoned by pro-German Czech people who had fled. The Russians did not take care of us. We therefore went to see the mayor of the village to ask for a pass, and then we took the train to Prague, but we could not go any further because the railroad tracks were impassable. We then decided to walk to the American zone, where they took care of us and repatriated us to Paris 13 days later, on May 22, 1945. We had to travel in cattle cars again because we could lie down in them: in a normal train, sitting on seats, our feet would have swelled up. When we got back to Paris, we went to the Hotel Lutecia, where we met up with our uncle and aunt. I only weighed about 75 lbs. (35 kg).

Our family members from Marseille who were deported never came back from the camps.

We managed to get our apartment and our business in France back, albeit with some difficulty. I didn’t want to go back to school because I wasn’t the academic type and also didn’t want to be with younger people who hadn’t been through everything that I had. I worked with my mother as a fabric cutter and then I opened a store.

I survived the deportation, but it affected me enormously, and I sometimes feel guilty because so many people lost their lives there, including my father and some of my family. Whenever I think about it, I wonder how people can do such things.

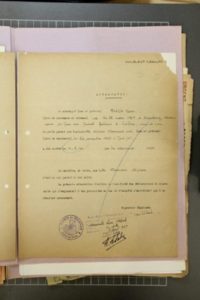

In 1949, we needed to obtain certificates to prove our involvement in the resistance: Simone and Lison Bloch testified that we had been active members of the Resistance, as did Georgette Cuperman and Mauricette Olschanezky Marcelle Qtark in 1950. We wanted to be recognized as deported Resistance fighters, rather than solely as Jewish deportees. An investigation was conducted in order to verify our claims.

On October 5, 1993, I received notification that my application for the status of “Deported Resistance fighter” had been approved. I had submitted my application on January 23, 1952. At that time, I was Myriam Baumerder, née Kleimann, and I was living at 76 avenue de Suffren in Paris, postcode, 75015. Unfortunately, my request was ultimately denied. I would have liked it to have been granted.

On June 26, 1950, I was adopted by Nathan Piper, my mother’s second husband, as my father had never returned after having been deported.

I got married in 1954 to Armand Baumerder and we had two children, a son, Jean Claude, and a daughter, Cathy. Later on, we had grandchildren. I told them my story, as did my mother, in bits and pieces. I wrote a journal for my children and grandchildren. The fact that I was with my mother saved us both during those 11 months of hell. We were at the end of our tether, and another month would have been impossible to survive. I have never testified but I hope it will never happen again (excerpt from her 2005 video testimony).

Français

Français Polski

Polski