Paulette WIETRZNIAK

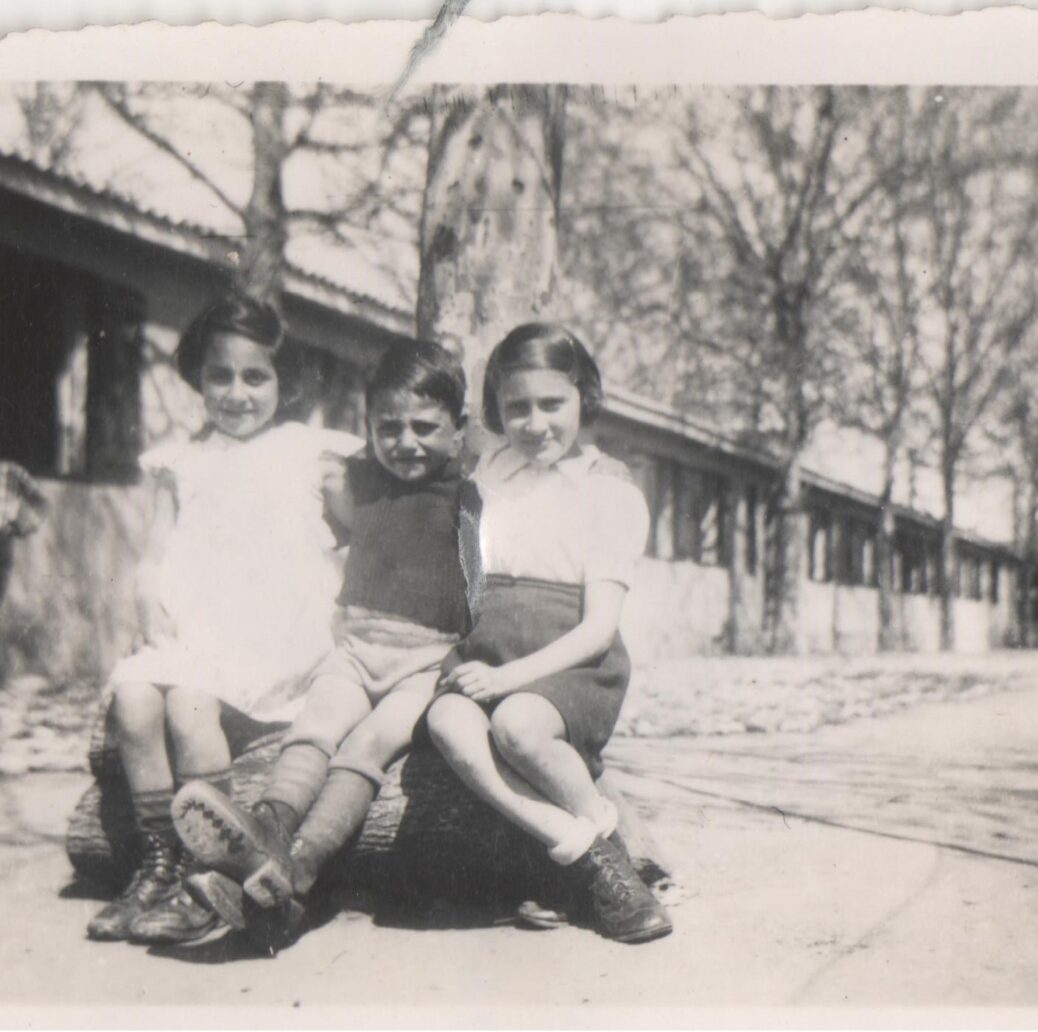

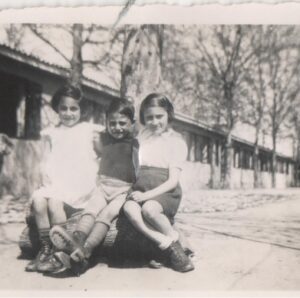

Photo thought to be of Paulette and Régine Wietrzniak with their cousin, Noël Wietrzniak, taken in around 1938. (Eve Wietrzniak’s collection)

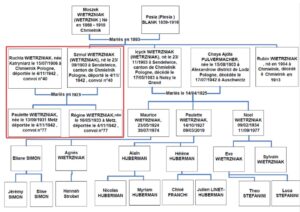

I. A family tree showing the links between the generations

This is the Wietrzniak family tree, starting with Moszek and Pesla, who died in Russian Poland in the early 20th century, and ending with the present generations who live in France. The section outlined in red includes Paulette and Régine Wietrzniak, Holocaust victims who were deported on Convoy 77, and their parents, Szmul and Ruchla. Eve, Sylvain, Agnès, Alain, Théo, Luca and Hannah, with whom we spoke earlier this year, have only been aware of their existence for a few years. The tree represents the links the family has forged with its past, thanks in part to our investigation. Here are our findings…

II. Life before the Holocaust

1. Chmielnick, in the early 20th century

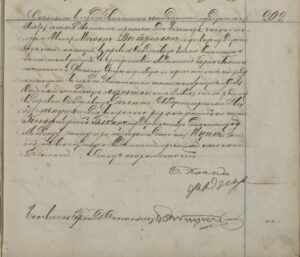

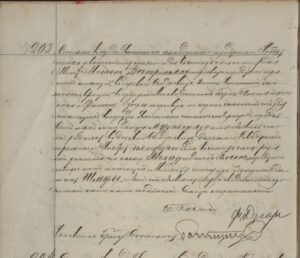

It all began in Chmielnick, in present-day Poland, at the very beginning of the 20th century. The town was in the Russian Empire in those days: ever since the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the part of Poland annexed by Russia had been known as the “Congress Kingdom”. This explains why Szmul and his brother Icyk’s birth certificates are in Russian. According to Olga Perrot, who translated them, they were written in Old Russian, which makes them more difficult to understand and translate. Also, the dates were recorded in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars, but we are only going to use the Gregorian calendar dates.

Both brothers’ births were registered on November 30, 1903, but they were declared to have been born a week earlier, on November 23. Their parents were Moszek Wietrzniak and Pesla Blank. In accordance with Jewish tradition, they would have been circumcised when they were eight days old. According to subsequent French records, Icyk was born in October 1903 and Szmul was born September of the same year! Eve explained to us that the two brothers were in fact born two years apart, but that Moszek, their father, declared both births at the same time, even though the older boy was two years old by then.

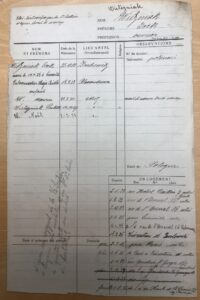

Birth certificates for Icyk (202) and Szmul (203), from the Polish State archives in Kielce. (sent by Ms. Agnieszka Jardel, translated by Ms. Olga Perrot)

We know virtually nothing about Szmul’s childhood in Poland, except that both of his parents were traders. We do know a third son, Ruben, was born in 1904, but he died in 1913. They boys’ father, Moszek, died in 1910, followed by their mother, Pesla, in 1916. Icyk and Szmul, aged just 13 and 15, thus became orphans. According to the family, an uncle took them in.

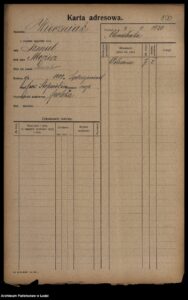

Eve found a residence record on a Jewish genealogy website that states that Szmul arrived in Lodz, in Poland, in June 1920, and lived in Północna Street, but it does not say when he left the city.

Szmul’s residence record from Lodz, dated 1920.

(Found by Eve on a Jewish genealogy website and translated by Ms. Véronique Chyla)

As we found no marriage record for Szmul in Metz, we contacted the Chmielnik municipal archives. We discovered that Szmul had got married there in a religious ceremony on May 14, 1929. His wife, Ruchla Katryniarz was born in 1906, also in Chmielnik, so we suppose that the couple had known each other well for some time. The marriage certificate reveals that neither of them was unable to sign their name. They probably had little or no formal education. A few months after they were married, they moved to Metz, in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France, where Szmul’s brother Icyk had been living since 1923. He had married Chaja Pulvermacher in 1924 in Lunéville, also in Meurthe-et-Moselle, and already had two children, Maurice, who was born in 1924, and Paulette, born in 1927.

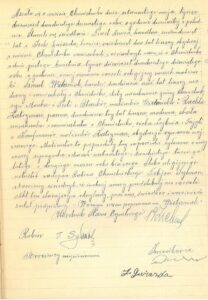

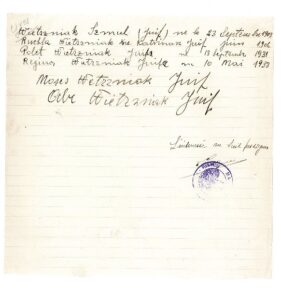

Szmul Wietrzniak and Ruchla Katryniarz’s marriage certificate, dated April 5, 1929 (Chmielnik municipal archives. Translated from Polish by Gustave Deremaux, Véronique Chyla and Renata Dupond).

2. The family’s life in Metz in the 1930s

According to Szmul and Ruchla’s residence record, Szmul arrived in France first. On December 9, 1929, he moved in with Icyk and his family, who lived at 18 rue Boucherie Saint Georges on the Sainte Croix hill in Metz. This confirms the story that had been passed down through the family: that it was Icyk who encouraged his brother to come to join him in France. Six weeks later, on January 20, 1930, Szmul moved to 9 rue Chèvremont, just a short walk away. Ruchla arrived from Chmielnik to join him on March 22.

We discovered that Szmul was a shoemaker, while Ruchla (who was known as Rachel in France) did not work outside the home. On September 13, 1931, Ruchla gave birth to a daughter, Paulette, at the Sainte Croix maternity hospital a little further up the hill. Paulette, like her cousin, was named after their paternal grandmother, Pesla, in keeping with the Ashkenazi tradition of naming children after their late relatives. A few months later, on July 1, 1932, the family moved again, this time to 34 rue d’Alger, which is in fact a continuation of the rue Boucherie Saint Georges, further up the hill. This was family’s last address in Metz. The apartment was probably a little larger than the previous one, because the couple had another daughter, Régina or Régine, on May 19, 1933. The French National archives hold Paulette and Régine’s naturalization files. As they were born in France, they were eligible for French citizenship by declaration, which was made by their parents. This shows that Szmul and Ruchla were keen to integrate into French society.

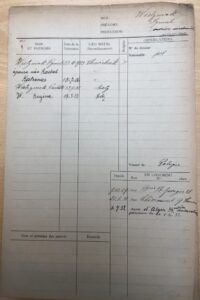

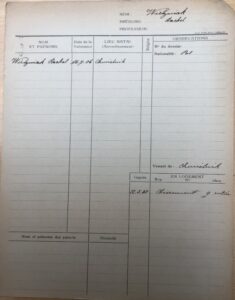

Szmul and Ruchla Wietrzniak’s residence records

(Metz municipal archives)

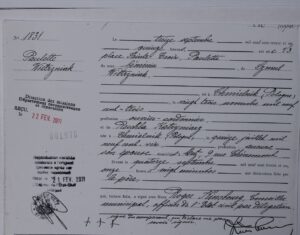

Copy of Paulette Wietrzniak’s birth certificate (from the file held by the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy, which led to the official acknowledgement in 2011 that she had died during deportation). Once again, we note that Szmul was unable to sign his name.

We know nothing more about the family’s life in Metz, but we suppose that Szmul and his brother Icyk remained close, as they lived not far from each other. Their children probably grew up together. In 1934, Icyk had a third child, Noël, who was almost the same age as Paulette and Régine, so was closer in age to his cousins than to his older brother and sister. Eve has a photo of her father, Noël, with two young girls to whom he appears to be very close to, so might well be Paulette and Régine. If so, it is the only known photo of the girls and confirms how close the two families and the cousins were.

Photo of Noël Wietrzniak with two girls who could well be Paulette and Régine. It was probably taken at Marvejols, in the Lozère department of France, in around 1938. (Eve Wietrzniak’s collection)

III. The beginning of a long journey

1. The Second World War

The Second World War began in September 1939. In June 1940, France signed the armistice with Germany, whose army had already taken over the northern half of France and all of the Atlantic coast. The Vichy regime, which came to power in July 1940, soon introduced anti-Semitic laws that mirrored those of Nazi Germany. Jews were required to register with the authorities, many lost their jobs and, as of June 1942, all Jews over the age of six had to wear a yellow star.

2. Yves, in the Charente Inférieure department of France: 1940

Icyk’s residence record shows that he left Metz as soon as hostilities broke out. We discovered that he fled to Montceau-les-Mines, in the Saône-et-Loire department of France, where his wife’s family was living, but we do not know when Szmul left.

Icyk Wietrzniak’s residence record (Metz municipal archives)

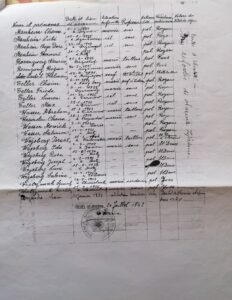

The next trace we found of the family dates from October 1940, in what is now the Charente Maritime department but was then the Charente Inférieure. They registered themselves as Jews in a village called Yves, on the Atlantic coast. We have a copy of the family’s declaration, which also includes a Moses and possibly an Abr(aham) Wietrzniak. We noticed a spelling mistake in the first name “Polet” (Paulette) and yet again, there is a note to say that Szmul was unable to sign his name. We also have an extract from the Yves municipal census: in total, based on their own declarations, 48 Jews were living in the village at the time.

We therefore conclude that in common with so many other Jewish families who left Metz between September 1939 and May 1940, the Wietrzniaks fled to Charente Inférieure to escape the threat of a German invasion. However, from June 1940 onwards, Yves, on the Atlantic coast, was officially in the German-occupied zone. Although they were hundreds of miles from the German border, the Jewish refugees thus found themselves trapped. The census in 1940 enabled the authorities to identify and keep track of all Jews living in France, which made it easier to persecute them thereafter. This was the first step in the extermination process: after the census, Jews were closely monitored. This meant that the following month, when Jews were banned from living along the Atlantic coast, the authorities were able to find them and transfer them to the occupied part of the Dordogne department.

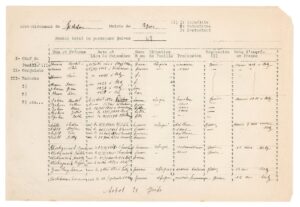

Census declaration for Szmul Wietrzniak and his family, made in October 1940 (Charente Maritime departmental archives)

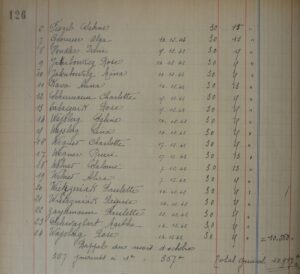

Extract from the census of Jews living in Yves in October 1940. There is also typed version of the list. (Charente Maritime departmental archives)

3. Saint-Michel-de-Rivière, in the occupied part of the Dordogne department: November 1940 – 8 October 1942

The family spent the next two years in the little village of Saint-Michel-de-Rivière, in the occupied part of the Dordogne department of France, just a few miles from the demarcation line. This small area of Dordogne in the occupied zone was temporarily attached to the Charente department. In November 1940, it became home to a dozen or so Jewish families who had followed a similar path to that of the Wietrzniak family.

The next trace we found of the family was once again in census records. This census, which was carried out on July 20, 1942, four days after the Vel d’Hiv roundup in Paris, provides further evidence of the way in which Jews were strictly monitored. It enabled the authorities to arrest many more of them in the following months.

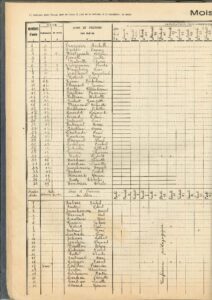

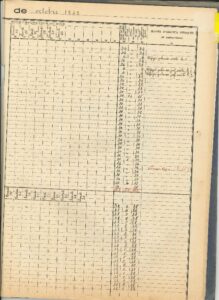

We have no details about the family’s time in Saint-Michel-de-Rivière, but based on other families’ accounts, we believe that they lived relatively peaceful lives and settled in well, despite the fact that most of the adults spoke little French. It was no doubt easier for the children, who picked up the language and spoke it in school. Régine is listed in the school register for 1942-1943, which is in fact the only one that the town hall still has.

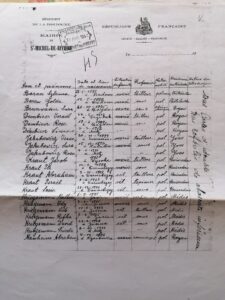

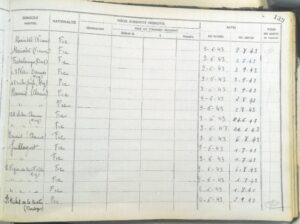

Census of foreigners living in St-Michel-de-Rivière on July 20, 1942

(Dordogne departmental archives)

Page from October 1942, Saint-Michel-de-Rivière elementary school register, 1942-1943

(Saint-Michel-de-Rivière municipal archives)

4. The Angouleme roundup of October 8, 1942: the heart-wrenching separation

The census of July 1942 paved the way for a large-scale roundup that targeted the entire Charente department and also the occupied area of the Dordogne department. During the night of October 8-9, 1942, at around 2 a.m., a group of French military police arrived in Saint-Michel de Rivière, arrested all the Jews, took them to Angouleme and held them in the Philharmonic Hall (now the Gabriel Fauré music academy). The school register for October 9 includes a note saying that Régine had been arrested and would no longer be coming to school.

A total of 442 people were rounded up and taken to Angouleme that day. Of those, the foreign Jews, who numbered 387 in total, 89 of them children, were transferred to Drancy internment camp, north of Paris, on October 15 and then deported on Convoy 40 on November 4, 1942. Paulette and Régine, who were French citizens, were therefore separated from their parents just a few days after the roundup, never to see them again. During our field trip to the Shoah Memorial in Paris, we were able to see Szmul and Ruchla’s internment records from Drancy.

The Philharmonic Hall in Angouleme, now the Gabriel Fauré music academy

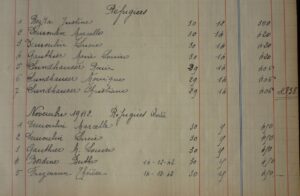

5. The Bon Pasteur convent in Angouleme: November-December, 1942

Along with 19 other young girls who had been separated from their parents, a local refugee committee sent Paulette and Régine to be cared for by the nuns at the Bon Pasteur (meaning Good Shepherd) convent in Angouleme. The city hall paid the convent a daily allowance for the girls’ food and board. The convent records state that several rooms were set aside to accommodate 21 Jewish children, ranging in age from 2 to 16. However, at the insistence of the Poitiers rabbi, probably Rabbi Elie Bloch, who originally came from Metz, they only stayed there for two months, after which they were placed with French Jewish families so that they could continue their religious education until such a time as their parents might come back. Paulette and Régine thus left the Bon Pasteur convent on December 15, but we have no information on the families who took them in, and we do not know if they were able to stay together. However, according to a report dated June 9, 1943, when they arrived at the Lamarck children’s home in Paris, run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews), they had arrived there from Angouleme. This suggests that they had remained in or near the city since the previous December.

Extract from the Bon Pasteur convent records, dated 1942 (in a letter from their archivist, received in November 2020)

Extract from the Bon Pasteur convent accounts, from November 1942

(Bon Pasteur convent archives)

6. The UGIF homes: June 1943 – July 22, 1944

The Vichy government founded the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews) in November 1941, at the behest of the Germans. It was supposedly intended to represent Jews in their dealings with the authorities and was responsible for social welfare. All Jews living in France were obliged to join it. All other Jewish organizations were closed down and their assets were transferred to the UGIF. The UGIF thus became a means of monitoring Jews and as such, it played a key role in the deportation policy. Following the first series of roundups, the UGIF began to set up children’s homes to take in Jewish children whose parents had been deported.

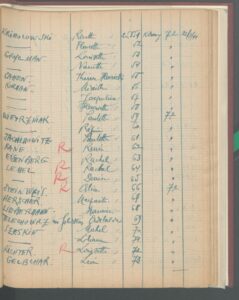

On June 9, 1943, the UGIF transferred a group of Jewish children, most of whom were not even aware that they were orphans, from the Charente department to UGIF center 28, the Lamarck center in Paris. As well as being a children’s home, the Larmarck center served as a sorting point. The names of the children were not listed alphabetically in the register, but in the order in which they arrived. Paulette and Régine were registered one after the other, suggesting that at least they were together when they were uprooted yet again. The register states that they left on September 3, 1943. The two girls were sent to another UGIF center, this time in Louveciennes, on the outskirts of Paris, where children were sent for summer vacations. According to another report, they did not go back to the Lamarck center until October 12.

Report from the UGIF Lamarck center dated June 9, 1943

(Shoah Memorial)

Page from the Lamarck center register for June 9, 1943

(Montmartre Jewish Center archives)

Report from the UGIF Lamarck center dated October 12, 1943

(Shoah Memorial)

What happened next is less clear. We know that at some point, Paulette and Régine were transferred to the UGIF center in Saint-Mandé, also in the Paris suburbs. We are not sure exactly when this was, but it could have been in February 1944, when another girl called Rachel Eisenbergis is thought to have been transferred there.

The Saint-Mandé home was located in a former nursing home at 5 Rue Grandville and was run by a Miss Cohen. In 1944, around 20 girls, all born in France between 1930 and 1939, were living there. The girls went to various local schools, depending on their ages. Paulette and Régine went to the Paul Bert elementary school on Rue Mongenot.

Arrest and deportation

At two o’clock in the morning on July 21, 1944, just a month before Paris was liberated, SS officer Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, together with several other men, arrived at the Saint-Mandé center to arrest all the children and their supervisors. They were all taken to Drancy internment camp.

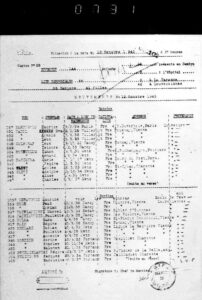

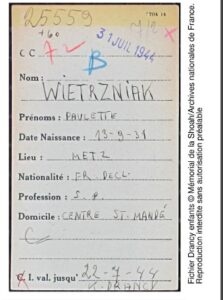

The camp transfer log shows that the two girls arrived and were registered at the same time, as they were issued consecutive numbers: Paulette’s was 25559 and Régine’s 25560. They were assigned to room 2 on staircase 7. During our visit to the Shoah Memorial, we were able to obtain a copy of Paulette’s internment card, which also refers to her sister’s card and lists her number (“+25560”).

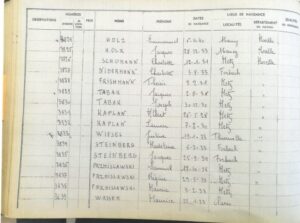

Drancy camp log book n°15, page dated July 22, 1944

(French national archives, ref. F/9/5788)

Paulette Wietrzniak’s internment record from Drancy

(French national archives, ref. F9 5748)

Nine days later, on July 31, 1944, the two sisters, Ms. Cahen and all the other children who had been arrested in the various UGIF homes in and around Paris were deported on Convoy 77 to the Auschwitz killing center.

When they arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, the two girls were almost certainly sent straight to the gas chambers and killed. Many years later, in 2011, they were officially declared to have died on August 5, 1944.

V. The importance of remembrance

During our interviews, several members of the Wietrzniak family told us that they felt uncomfortable with the French notion that we have a “duty to remember” and prefer to call it “remembrance work”, or simply “remembrance”. We have therefore decided to adopt this approach here in the last section of the biography, which focuses on the memorial plaques that have been erected in a number of places where Paulette and Régine lived.

In Metz

In the Polish synagogue in Metz, there is a commemorative plaque dedicated to the members of the Jewish community who were martyred at the hands of the Nazis. The name “Wischniak S” is inscribed on it. This spelling reflects the Yiddish pronunciation of the name Wietrzniak. Szmul’s brother Icyk survived the deportation but never went back to live in Metz, so he was not there to ensure that the name was spelled correctly. Additionally, it was only in 2012, at the request of his daughter Paulette, who is Paulette and Régine’s cousin, that the name of Icyk’s wife Chaja, who also died in the camps, was added.

The commemorative plaque in the Polish synagogue in Metz.

In Saint-Michel-de-Rivière

On October 8, 2022, a memorial was unveiled in honor of all the Jewish families who lived in the village between 1940 and 1942. The date was not chosen at random: it marked the 80th anniversary of the Angouleme roundup. The names of the Wietrzniak girls and their parents were listed on the banner that covered the memorial stone when it was unveiled.

The banner on the memorial in St-Michel-de-Rivière when it was unveiled on October 8, 2022

In Saint-Mandé

On May 25, 2023, a commemorative plaque was unveiled at the Paul Bert elementary school in Saint-Mandé in honor of the 41 Jewish children who were arrested there and subsequently deported. 39 of them, including Paulette and Régine, were students at the school. The plaque also reminds visitors that in total, some 11,400 Jewish children were deported from France.

The inscription on the memorial ends with the phrase “LET US NEVER FORGET THEM”

The commemorative plaque at the Paul Bert school in Saint-Mandé

At the Shoah Memorial in Paris

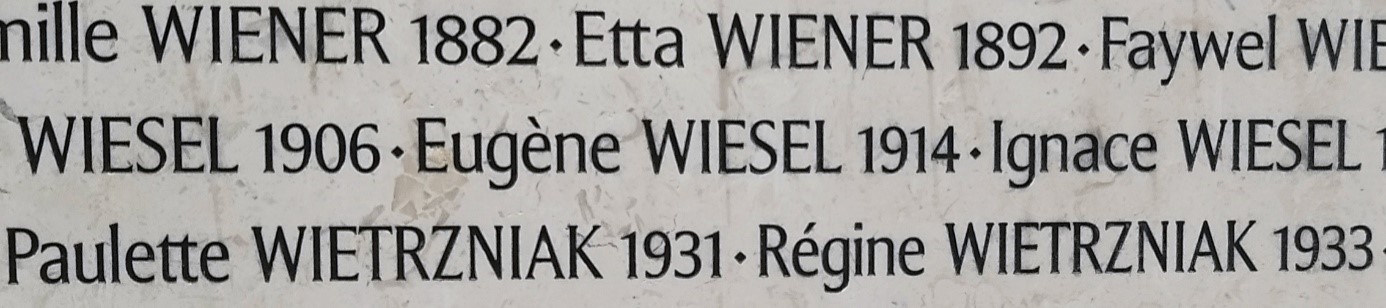

The Shoah Memorial in Paris, which opened in 2005, is a memorial museum dedicated to the Jews who were persecuted and exterminated in World War II. Originally founded in 1956 as the Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr, it plays an essential role in passing on history and ensuring that this tragedy will never be forgotten. It also houses a museum with permanent and temporary exhibitions, as well as a documentation center that holds invaluable records related to the Holocaust. The names of the 76,000 Jews deported from France are engraved on the Wall of Names. We visited the memorial on January 29, 2025 during a field trip and were able to take a few photos, including this one:

The section of the Wall of Names on which the names of Paulette and Régine are inscribed

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank everyone who helped us with this project, in particular the members of the Wietrzniak family, who we were privileged to have the opportunity to work with. We would also like to thank Mr. Gérald Sim, a history and geography teacher from La Rochelle, in the Charente Maritime department of France, who provided us with many useful resources that contributed greatly to our research.

Français

Français Polski

Polski