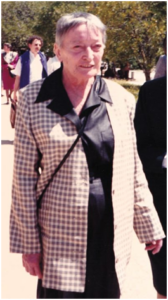

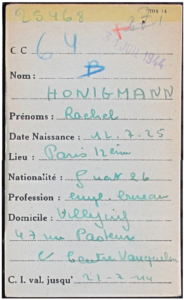

Rachel HONIGMANN

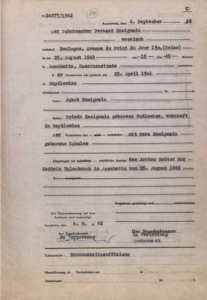

Photograph of Rachel Honigmann. Date unknown.

Source: Yad Vashem

We, the 9th grade students of class 3C at the Guy Môquet middle school in Villejuif, in the Val-de-Marne department of France, have endeavored to retrace Rachel Honigmann’s short life. This joint project began with a visit to the Val-de-Marne departmental archives in Créteil, where we studied the archives provided by the Convoy 77 team. We worked alongside Ms. Clair, our History and Geography teacher, Ms. Hourch, our French teacher and Ms. Mazuer, the school librarian, with the help of Nathalie Baron, the liaison teacher at the departmental archives. Records from the Shoah Memorial in Paris, our visit to the Shoah Memorial in Drancy to follow in Rachel’s footsteps, and some Internet research all helped us to complete our investigation. However, much of Rachel’s life still remains a mystery.

In this biography, we begin by focusing on Rachel’s family. We then turn to her arrest in the children’s home on rue Vauquelin and her internment at Drancy, followed by her deportation. Lastly, we ask if there are any remaining traces of Rachel and her family in Villejuif.

Soumia Ahrika, Ibrahim Mohamad, Aaron Djougba and Adel Amourat are the students who wrote this biography.

1 – Rachel’s family

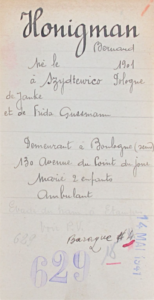

Rachel Honigmann was born on July 12, 1925 in the 12th district of Paris. Born into a Polish family, she was naturalized as a French citizen on June 18, 1926. Her father’s surname was Bernard Honigman, with one “n” at the end, while Rachel’s had two: we do not know why this was the case. According to the Shoah Memorial records, her father was born in Poland on April 25, 1901. When he first emigrated to France, he lived at 130 rue du Point du jour in Boulogne-Billancourt, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of France. He worked on the fairgrounds or markets. On June 25, 1942, after being interned in Pithiviers camp, he was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 4. He died on August 25, 1942.

Photograph of Bernard Honigman. Source: Shoah Memorial

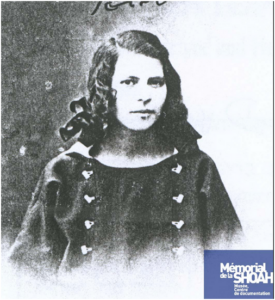

Pithiviers camp record card. Source: Shoah Memorial, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5759_290316_L et FRAN107_F_9_5759_290317_L

Bernard Honigman’s death certificate, drawn up at Auschwitz, which says that he died of heart failure. Published following Jacqueline Passentin’s testimony about her father. Source: Auschwitz museum

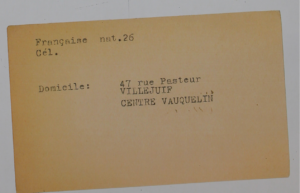

Rachel’s mother, Biewoja Honigman, née Chalow, was born in Plonsk, Poland on May 18, 1899. We found no evidence that she went out to work. According to the testimony of Rachel’s sister, Jacqueline Passentin, née Honigmann (1930-2019), Biewoja and Bernard Honigman met in France but were separated when Jacqueline was born. We only know of one address where Rachel, her sister and her mother lived: 47 rue Pasteur in Villejuif.

47 rue Pasteur à Villejuif. June 2024

Photo taken by Aaron Djougba

It was there that Biewoja Honigman was arrested on July 16, 1942. Did this happen as part of the Vél’ d’Hiv roundup? How did Rachel and her sister manage to avoid being arrested? Biewoja was interned in Drancy camp and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 36 on September 23, 1942. She never came back.

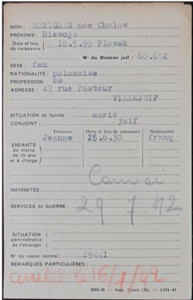

Photograph of Biewoja Honigman

Source: Shoah Memorial

Prefecture record, on which Rachel’s sister is listed as Jeanne, rather than Jacqueline or Jeanine (another name found on some records). Drancy record card

Source: Shoah Memorial

2 – The girls’ home on rue Vauquelin

After their mother was deported, Rachel and Jacqueline left Villejuif and went to stay in a children’s home for girls run by the UGIF (Union générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews), at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris. This is confirmed by a testimonial sheet from the French Committee for Yad Vashem.

In her testimony, Jacqueline Honigmann mentioned the ORT (Organisation reconstruction travail, or Organization for Rehabilitation through Training) which was then based on rue des Saules in the 18th district of Paris. We therefore sent an e-mail to ORT France, who in turn sent us an extract from the register of students enrolled in ORT courses, on which Rachel’s name is listed. We were surprised to find on it a different address: 150 boulevard Magenta – Paris. Her brief, sporadic attendance at classes is also strange. It says that she took the sewing course.

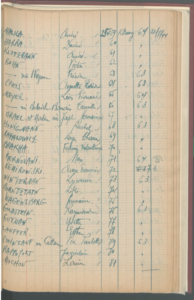

Page from the register of students enrolled in ORT courses in Paris during the Occupation

Source: ORT France archives

However, it was in the home on rue Vauquelin that Rachel was arrested on the night of July 21-22, 1944. In retaliation for a Resistance operation against the Das Reich division (2nd SS armored division), which had been deployed to reinforce the German forces on the Normandy front, SS Commander Aloïs Brunner had all the children from the UGIF homes arrested. Rachel was interned in Drancy camp along with all the other girls from the home.

Records from the French National archives

Source: French National archives at Pierrefitte

But what happened to Rachel’s sister? We discovered from her testimony that she was being kept hidden in the countryside at the time. Perhaps she was already staying with Micheline Bellair, who saved her and other Jews during the German occupation? In 1988, Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, named Micheline Bellair one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

Micheline Bellair at Yad Vashem in 1988

Source: Yad Vashem

3 –Drancy camp and the deportation

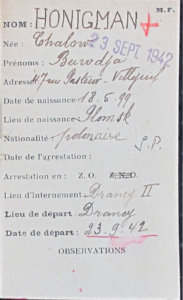

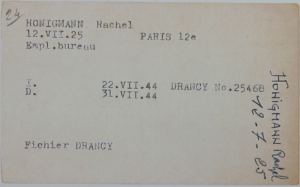

Rachel Honigmann was interned in Drancy camp on July 22, 1944. The letter B on her interment card means that she was “deportable immediately”.

Drancy camp record card

Source: French National archives at Pierrefitte, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5701_158890_L

As the camp’s transfer register shows, Rachel was assigned to a room on the 4th floor of staircase 6.

Drancy transfer register

Source: French National archives at Pierrefitte, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5788_0041_L

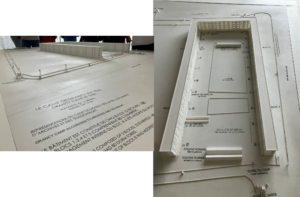

During our visit to the Shoah Memorial in Drancy, we were able to get a clearer idea of the camp layout.

Model of Drancy camp at the Shoah Memorial in Drancy

Photo taken by Stéphanie Mazuer

On July 31, 1944, Rachel was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. We have only found an indirect account of what happened to her in Germaine Wagensberg’s biography here on the Convoy 77 website, in which Rachel Honigmann is mentioned by name. Germaine Wagensberg was also arrested during the roundup in rue Vauquelin and was deported on the same convoy as Rachel. She later described how the deportees were crammed into cattle cars at Bobigny station, that the journey was “horrible”, “the hardest of all”, and that sanitary conditions were appalling. It took three days for the train to reach Auschwitz. The Nazis carried out the selection process as soon as it arrived. For the deportees, this meant life or death. Germaine recounted how the manager of the UGIF home got separated from the rest of the girls. Rachel refused to leave her and clung to her arm. Neither of them passed the selection.

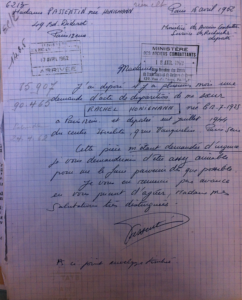

Many years later, Rachel’s sister, who by then had married and become Jacqueline Passentin, had to jump through hoops with the authorities to have a death certificate issued for Rachel.

Letter from Jacqueline Passentin to the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War

Source: HONIGMAN Rachel © French Defense Historical Service in Caen, dossier 21 P 258 458

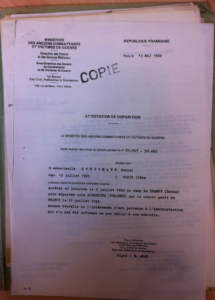

She received only a missing person’s certificate on May 15, 1962. The authorities refused to issue death certificates in cases where “there are no documents or testimony relating to the dates and places of death”

Missing person’s certificate, issued in 1962

Jacqueline Passentin had to wait until June 20, 1975 to finally obtain judgement in lieu of a death certificate. However, the place of death was recorded as Drancy, even though the missing person’s certificate stated that she had been “deported to Auschwitz”.

The official deed issued on June 20, 1975, which serves as a death certificate.

We were intrigued by one particular sentence in this official deed from Villejuif…

4 – What if we could make up for a long-forgotten oversight?

The sentence reads as follows: “Orders the transcription of the present provision into the civil status registers of: 1°) the town hall of Drancy, place of death [?], and 2°) the town hall of Villejuif, the last place of residence of the deceased”.

We had already contacted Villejuif’s municipal archives department, who assured us that they had no information about Rachel Honigmann or her mother. “They do not appear on the 1936 census, nor on the electoral lists from the late 1930s, nor on the lists of deportees from Villejuif that were drawn up at the end of the Second World War”.

We ran out of time to search the civil registry records, sadly. We were hoping to be able to make up for this oversight and request that the names of Rachel and her mother be inscribed on the memorial to the deportees from Villejuif in the Pablo Neruda park.

Monument to the Jews deported from Villejuif

Photo taken by Emilie Claire

Français

Français Polski

Polski